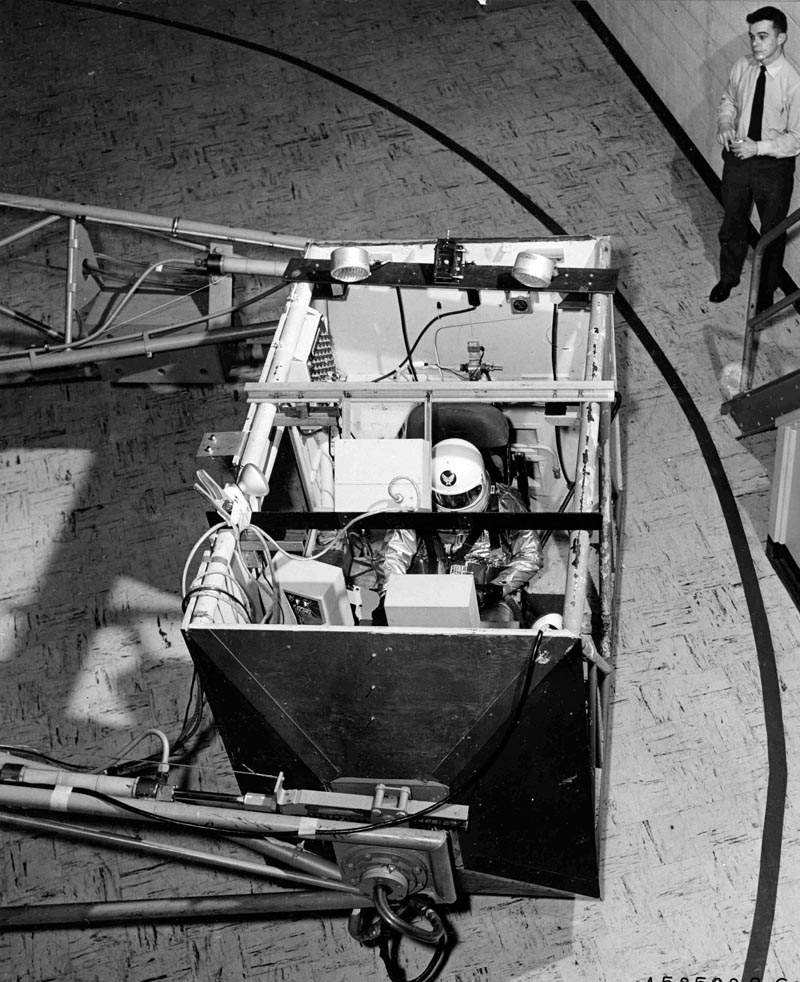

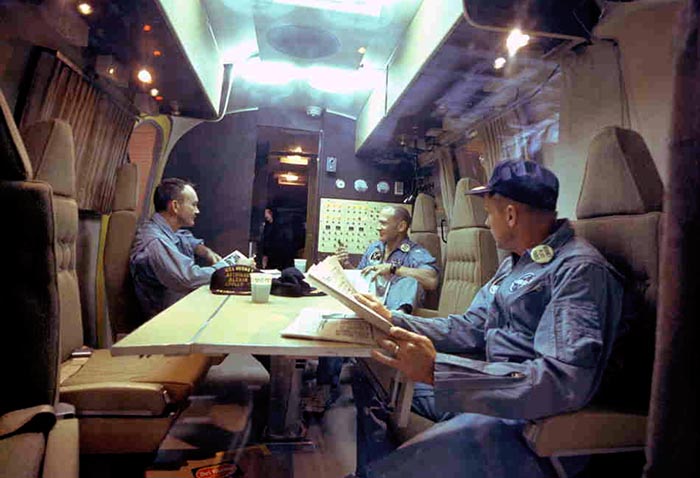

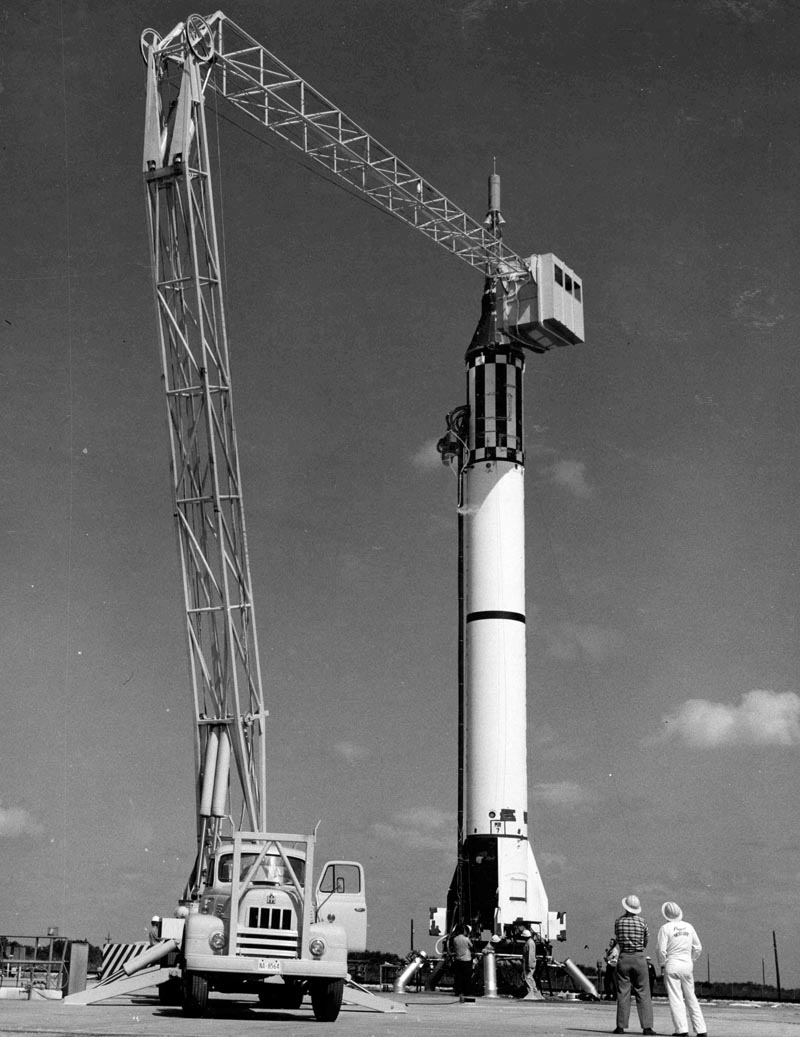

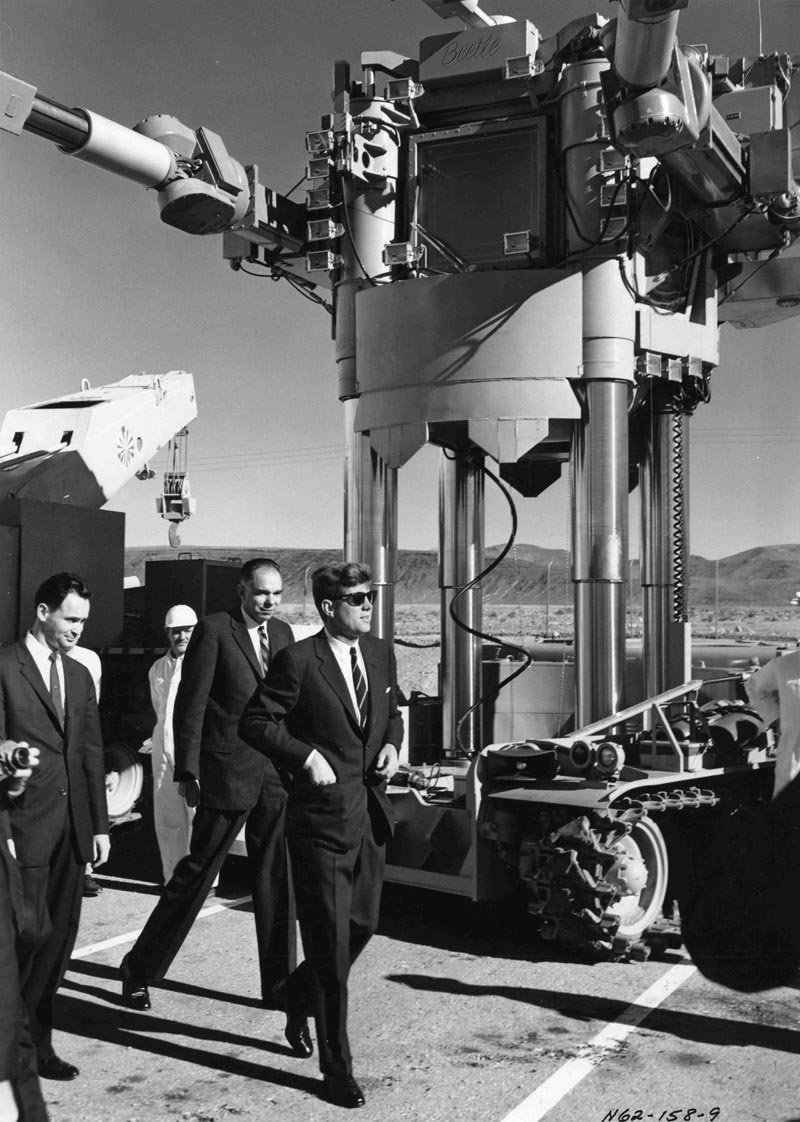

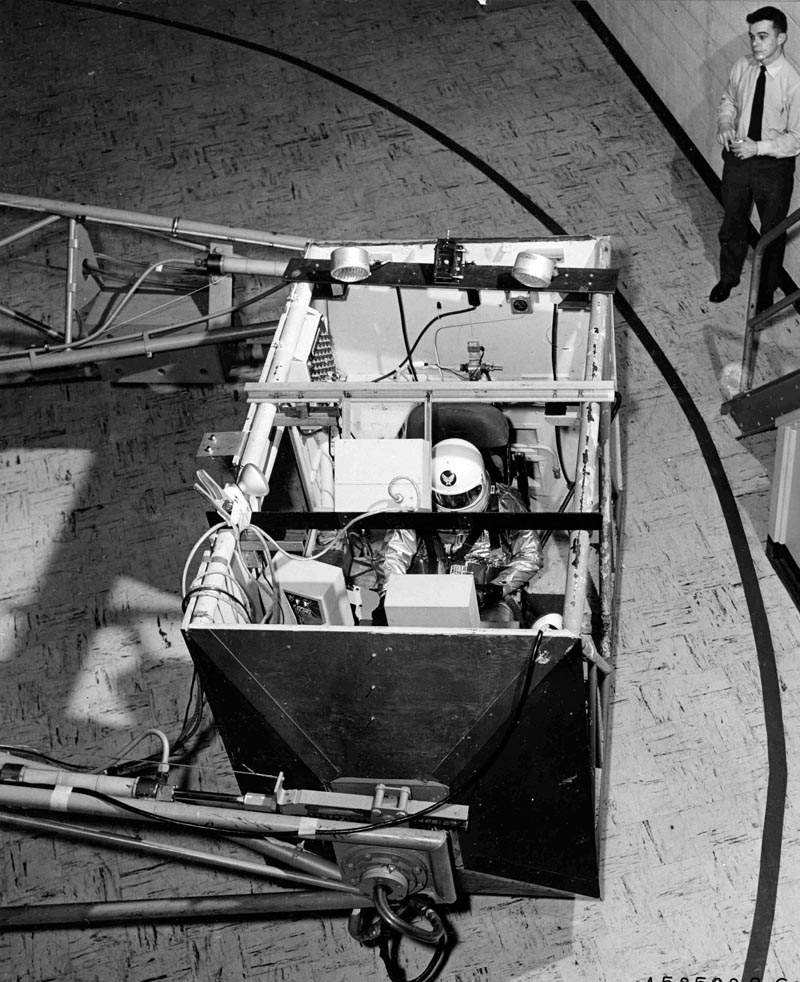

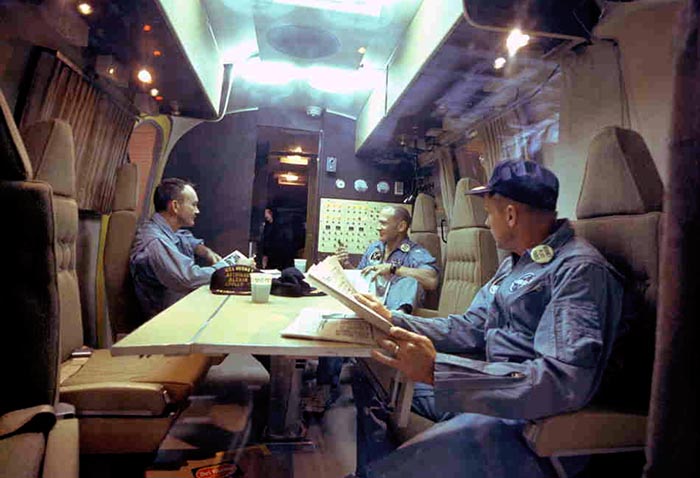

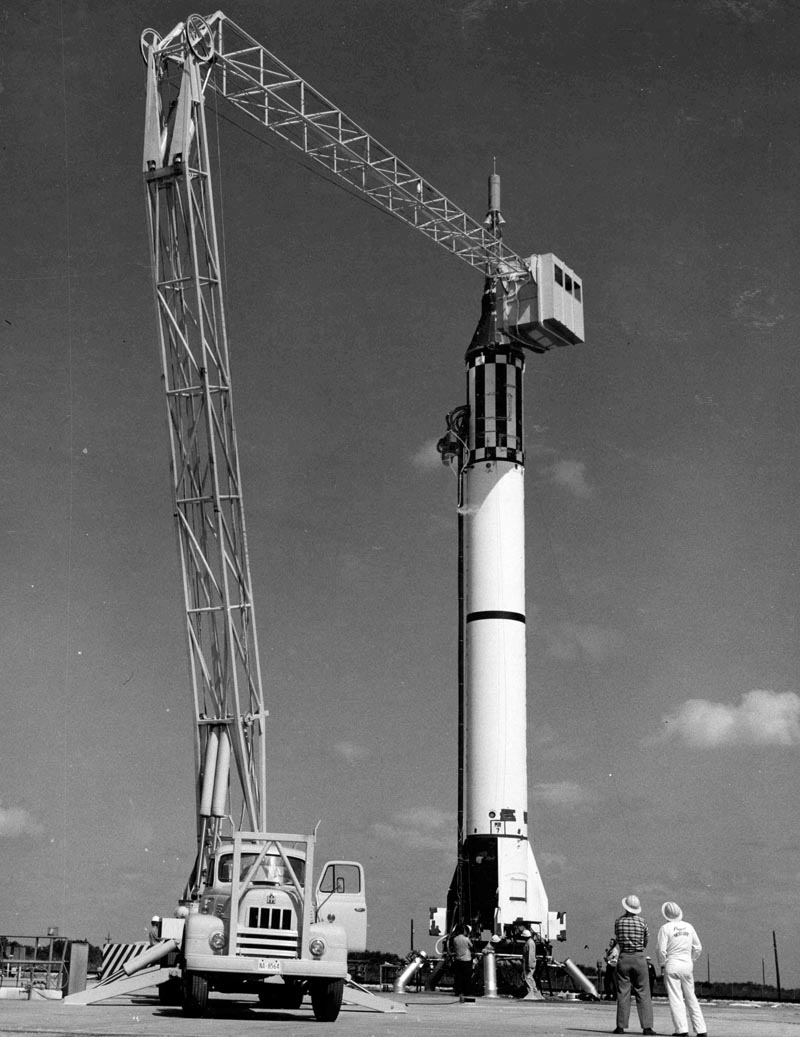

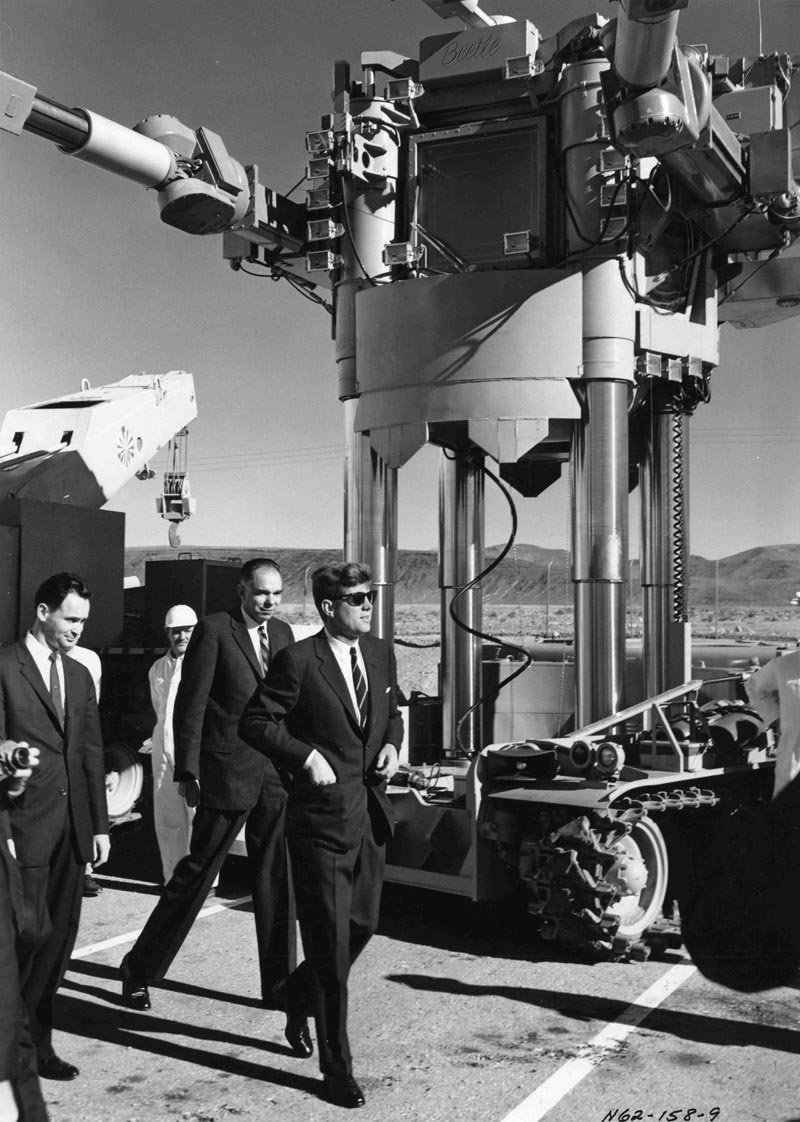

[Image: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Image: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

Nicholas de Monchaux is an architect, historian, and educator based in Berkeley, California. His work spans a huge range of topics and scales, as his new and utterly fascinating book, Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo, makes clear.

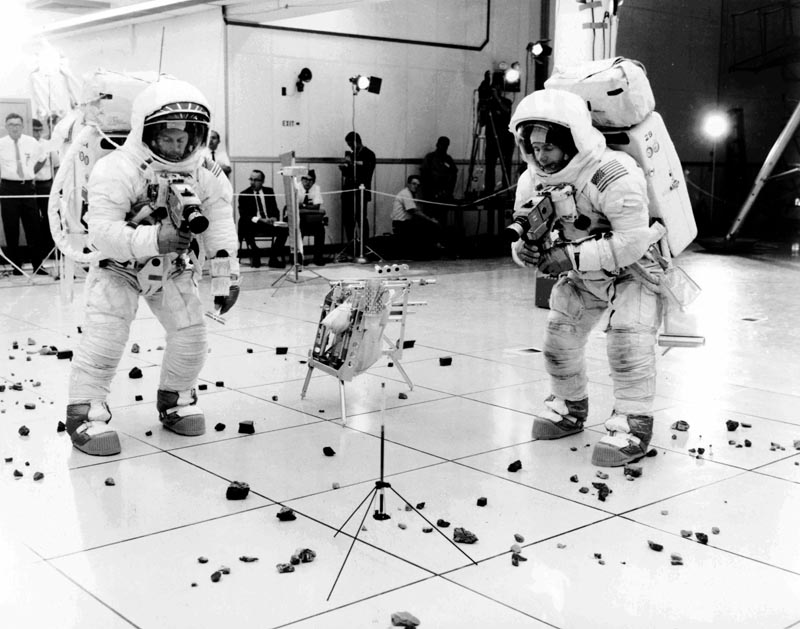

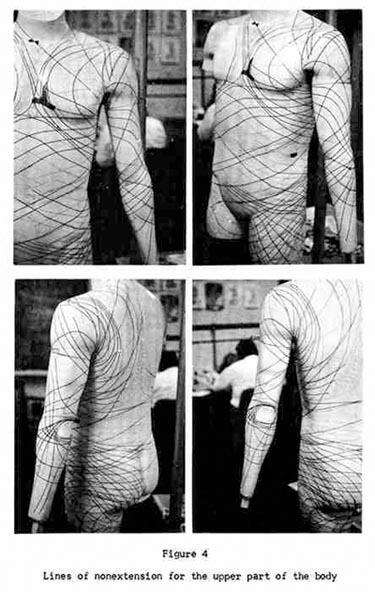

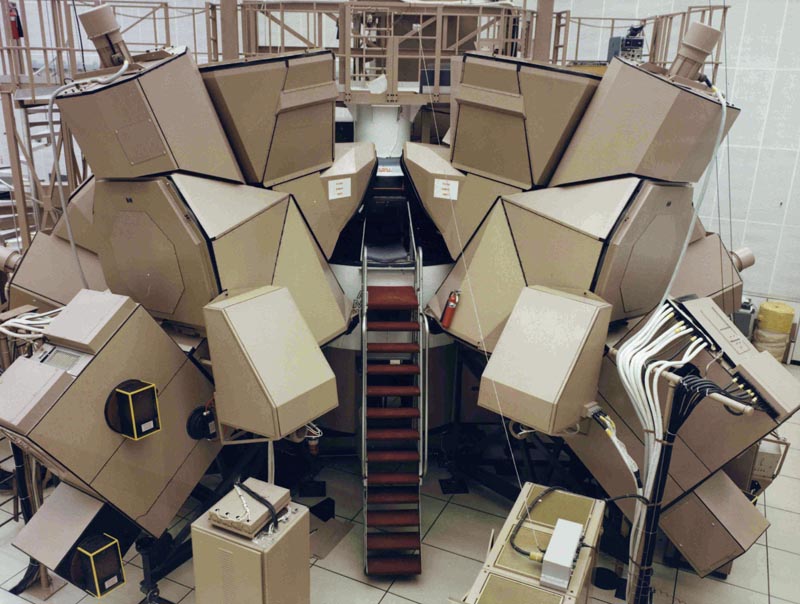

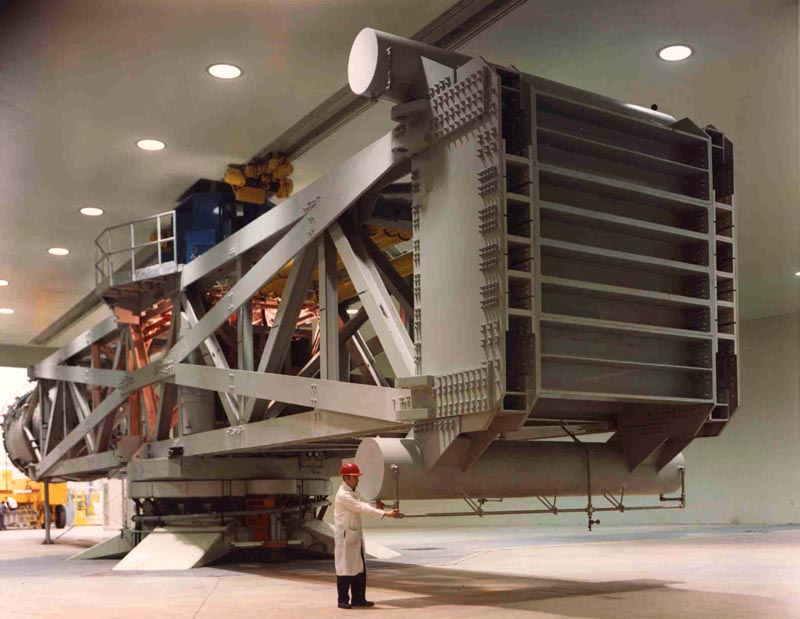

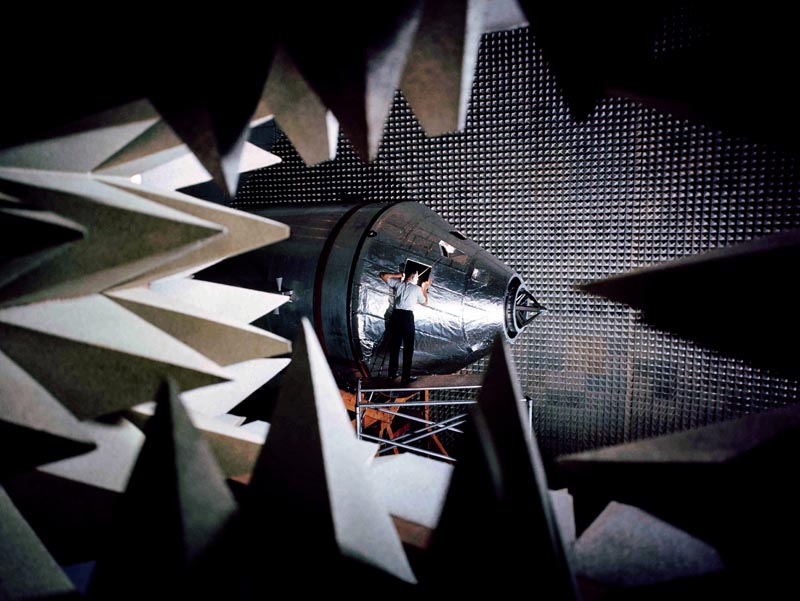

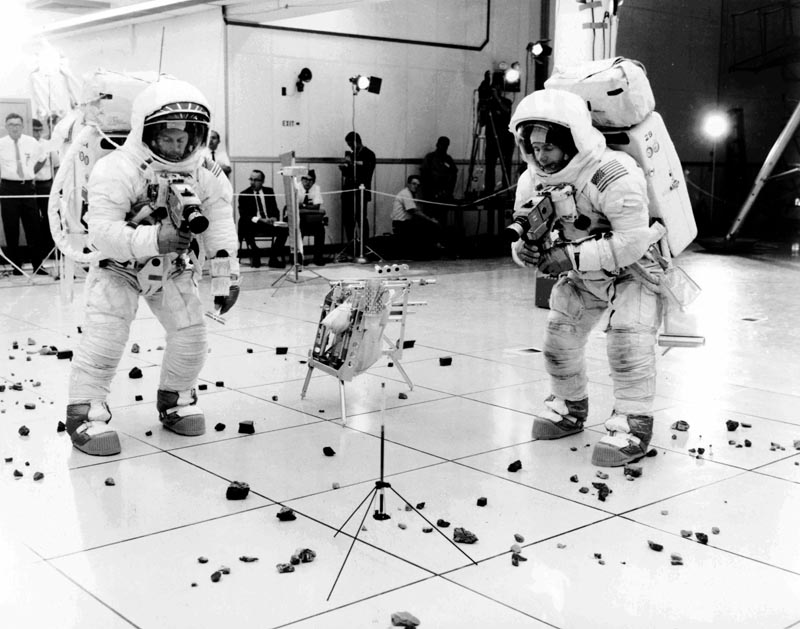

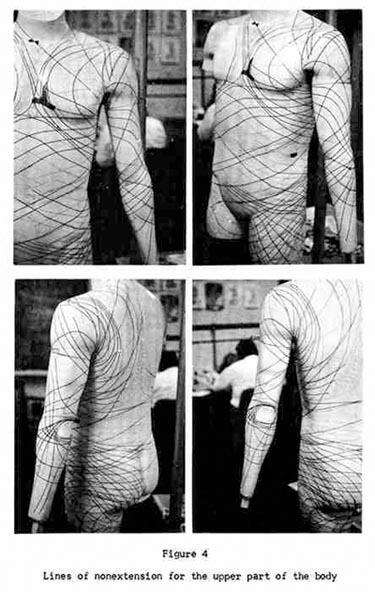

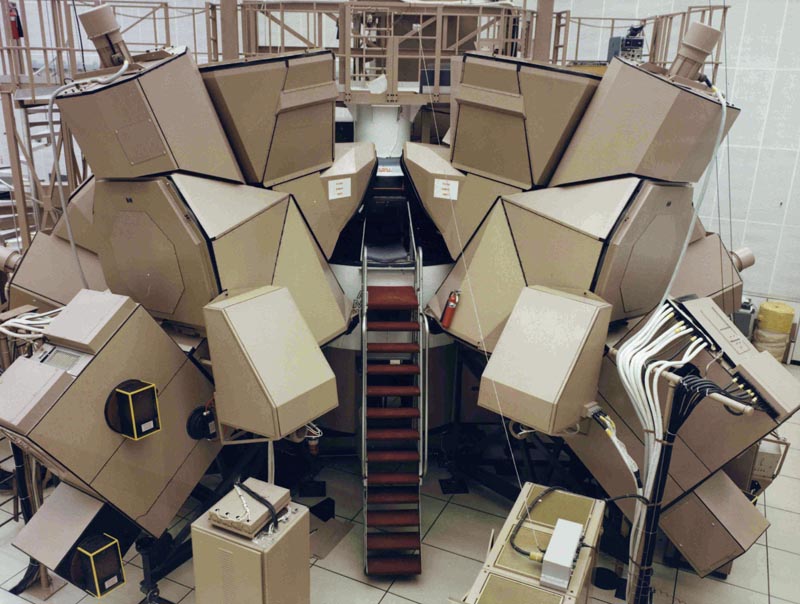

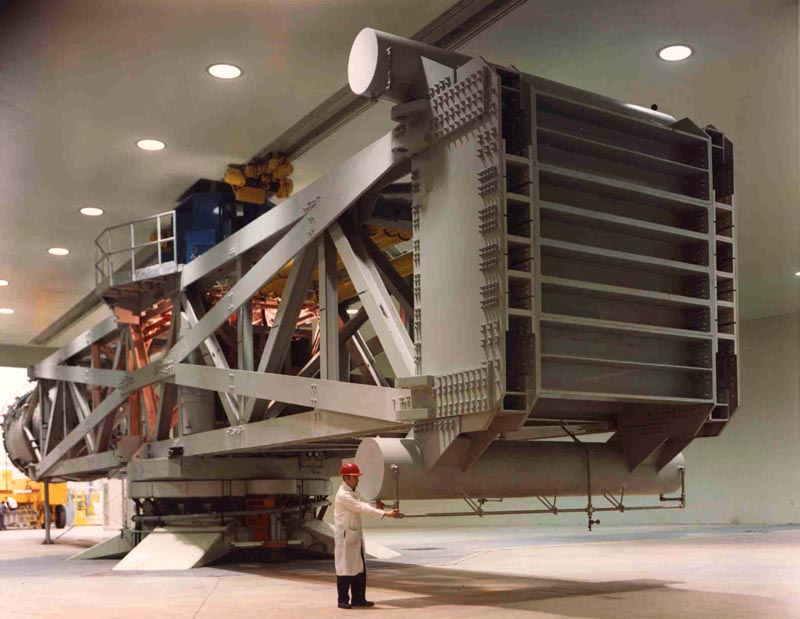

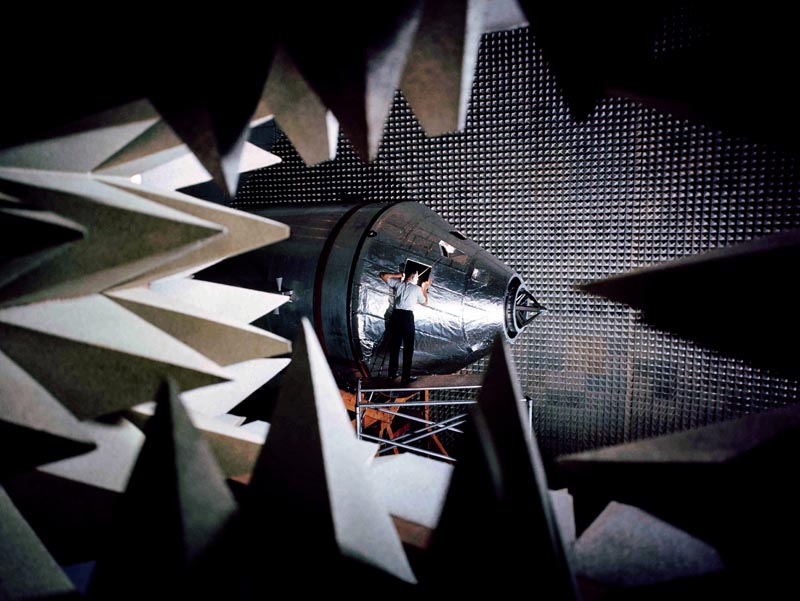

From the fashionable worlds of Christian Dior and Playtex to the military-industrial complex working overtime on efforts to create a protective suit for U.S. exploration of the moon, and from early computerized analyses of urban management to an “android” history of the French court, all by way of long chapters on the experimental high-flyers and military theorists who collaborated to push human beings further and further above the weather—and eventually off the planet itself—de Monchaux’s book shows the often shocking juxtapositions that give such rich texture and detail to the invention of the spacesuit: pressurized clothing for human survival in space.

[Image: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Image: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

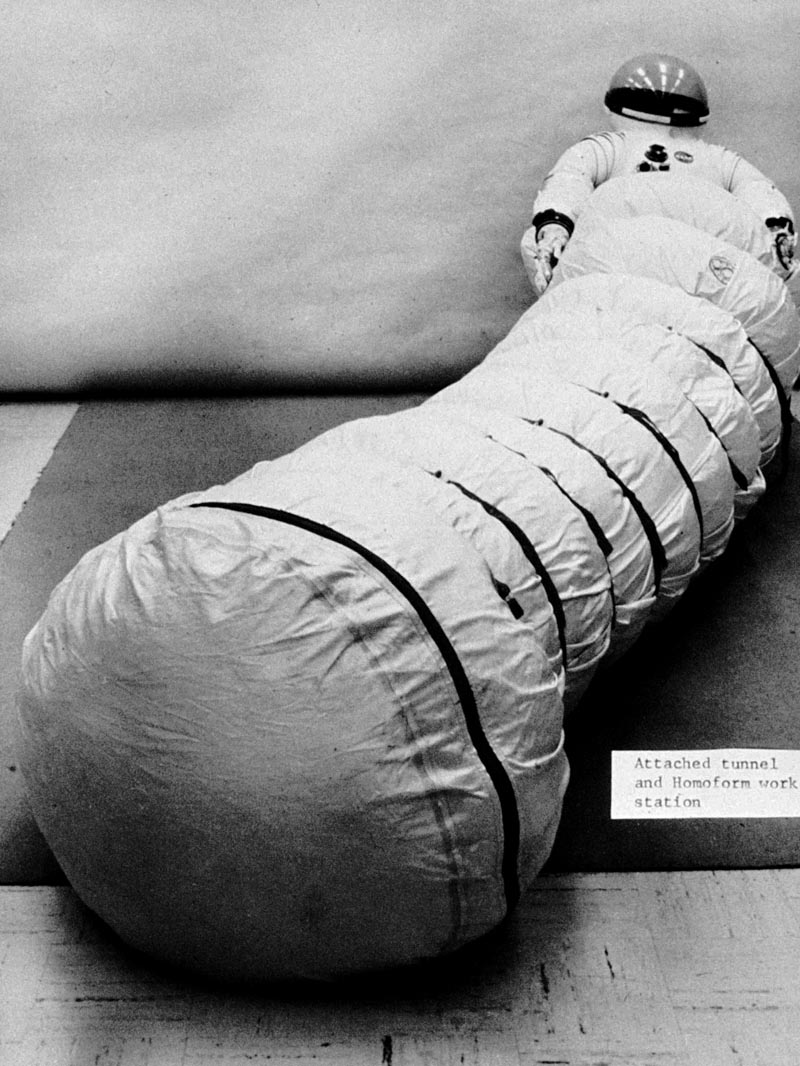

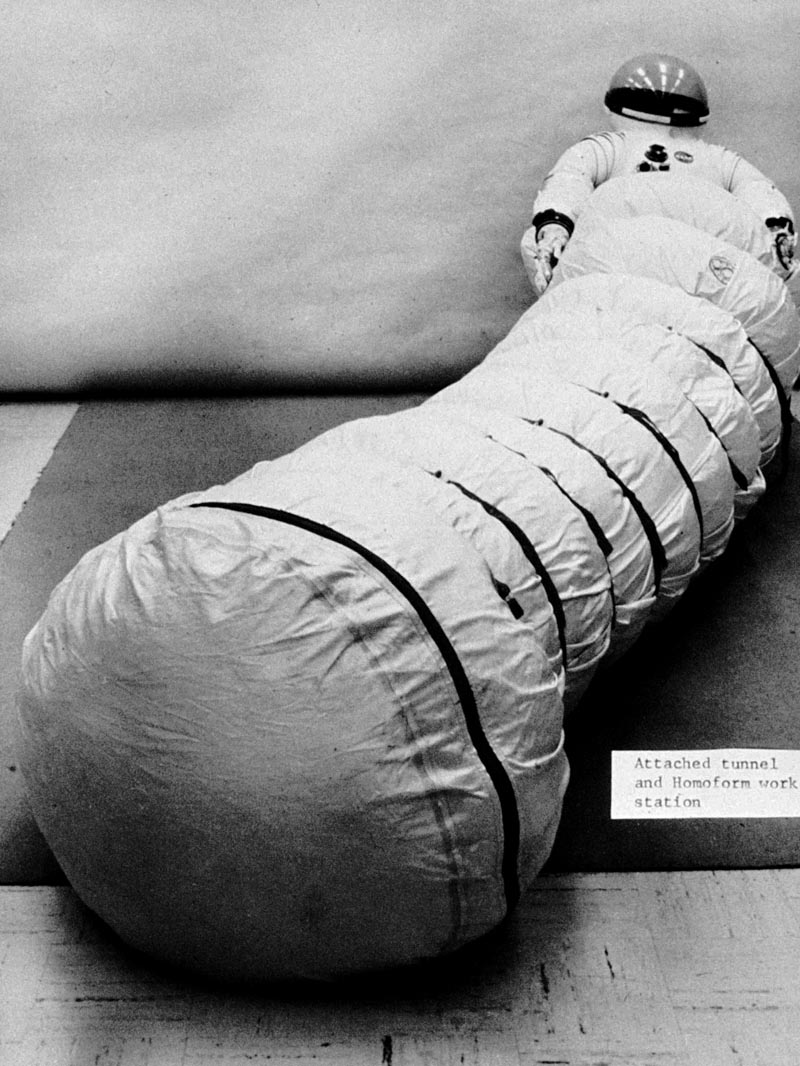

Bridging the line between clothing and architecture, the spacesuit is a portable environment: a continuation of habitable space, safe for human beings, capable of radical detachment from the Earth. That a “soft” and pliable suit designed by Playtex—manufacturer of women’s underwear—would beat the “hard,” armor-like suit design of military contractors is the surprising core story of de Monchaux’s research.

[Image: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Image: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

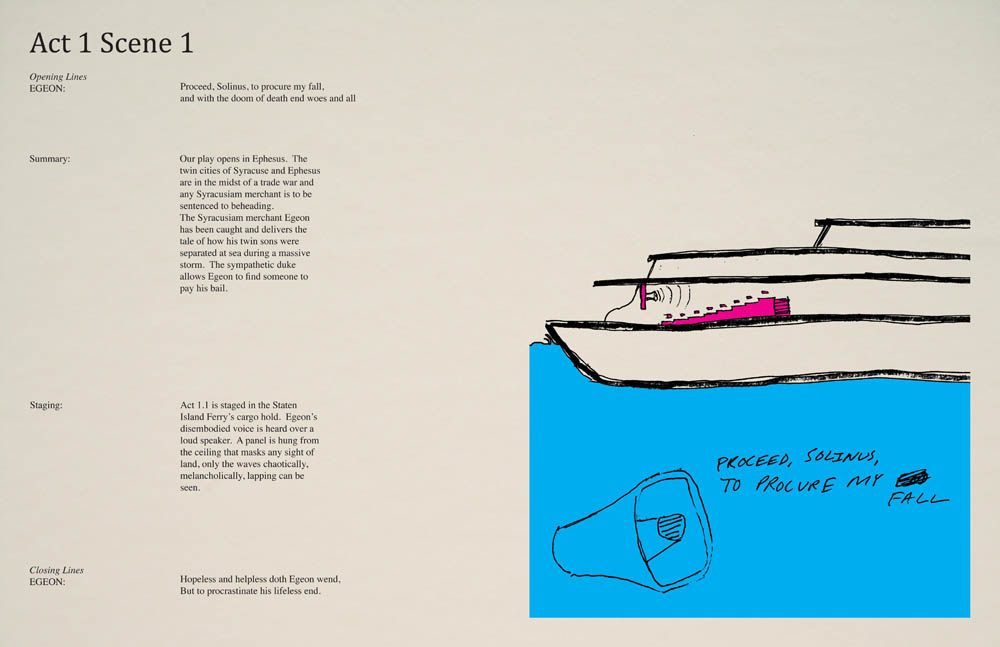

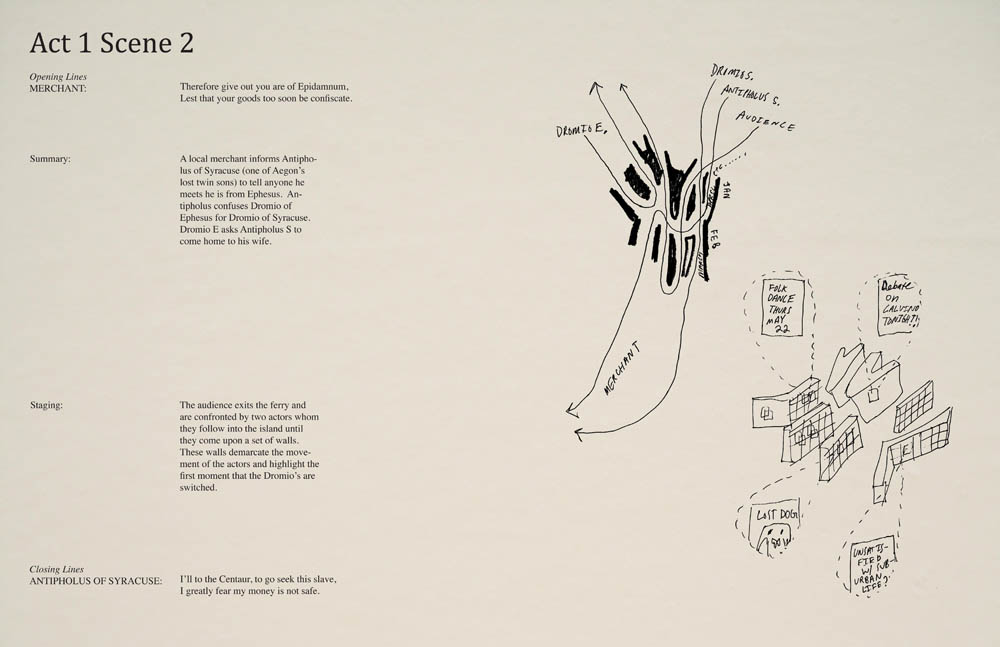

In the following Q&A, BLDGBLOG speaks with de Monchaux about his book; about his newly announced architectural design track at UC-Berkeley, called Studio One; about the risks and rewards of parametric design on an urban scale; and about his ongoing experiments with architectural representation, including analyses of food production and delivery and a technical interrogation of the complex digital tools we use to map empty spaces in our cities. We video-chatted on Skype.

• • • [Image: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Image: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

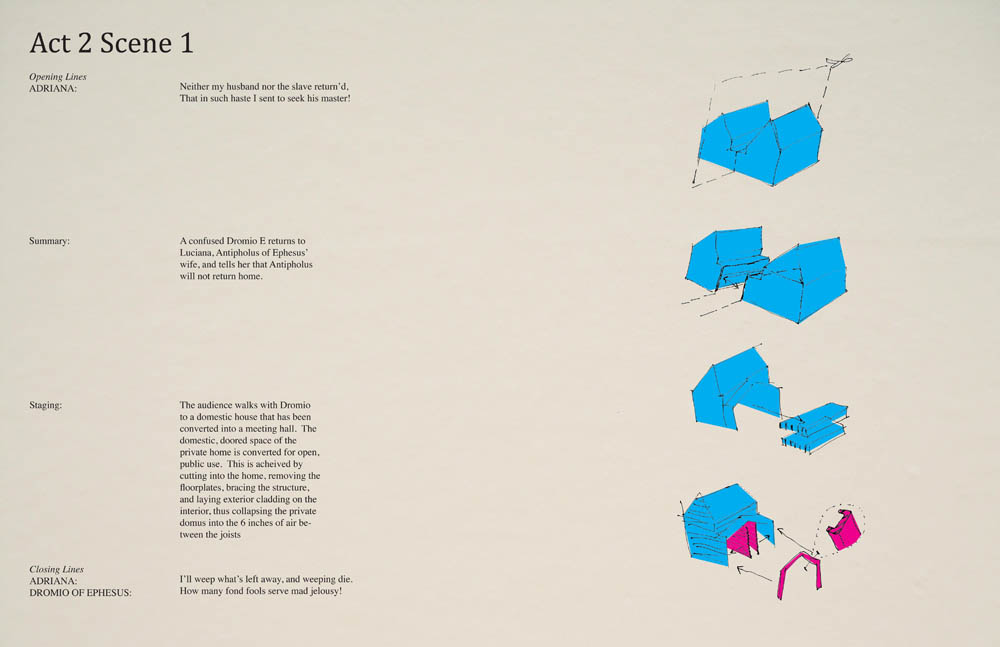

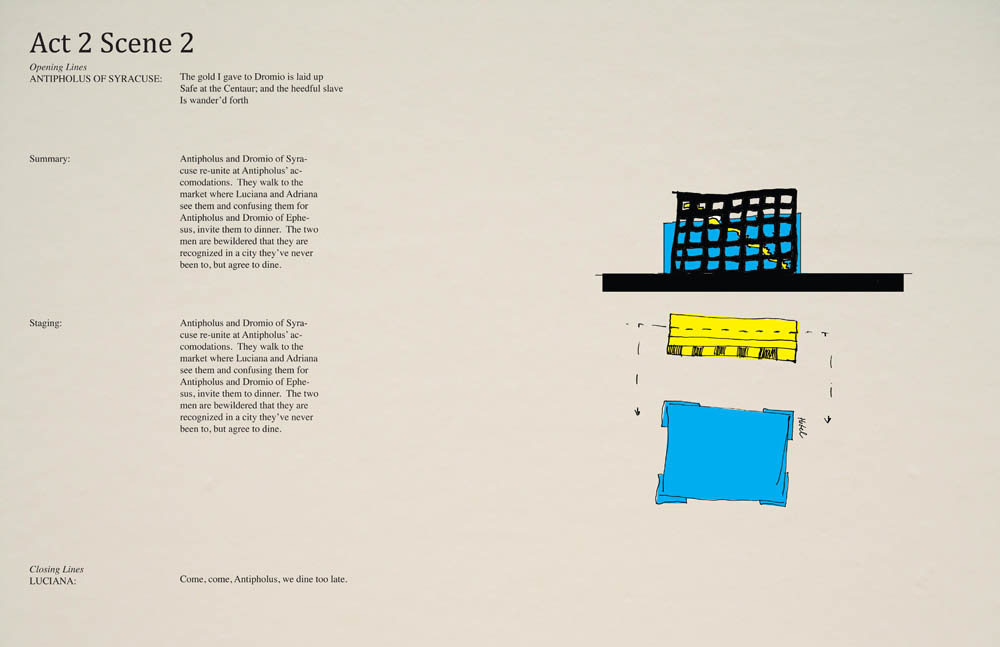

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious about the origins of the book: did you start off researching the history of systems engineering, only to stumble upon this emblematic object—the Apollo spacesuit—or were you hoping to write a design history of the spacesuit, only to discover that it was connected to these hugely diverse topics, such as postwar urban management and complexity theory?

Nicholas de Monchaux: The project itself really has two origin stories. One is when I first began to research spacesuits, as a graduate student: I expected there to be a single historical narrative. I expected that someone had already written extensively about the Apollo spacesuit, because it’s such an iconic object of the 20th century. But there was very little writing to be found.

Then, in 2003, I was invited to give a lecture at the Santa Fe Institute, which was a slightly intimidating thing to do—I was on the same bill as James Crick, Stewart Brand, and all these other heavyweights! I was looking for a way to discuss the essential lessons of complexity and emergence—which, even in 2003, were pretty unfamiliar words in the context of design—and I hit upon this research on the spacesuit as the one thing I’d done that could encapsulate the potential lessons of those ideas, both for scientists and for designers.

The book really was a melding of these two things. One is very much a situation where the chapters alternate between a focus on the object itself and its astonishing history—being made by Playtex, who was an underdog in the whole suit-design process, and that suit’s hand-crafted nature, etc.—and the other is an equally layered but very outward-looking narrative, from the vacuum of outer space to early ideas of computing, simulation, the body, cybernetic theories of urbanism, etc. etc.

Just as the structure of the spacesuit allowed many different approaches to be hybridized, from girdle-making to military-industrial engineering, so too did the structure of the book allow these complex internal and external narratives to be bound together into a single volume.

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

BLDGBLOG: At its most basic, your book tells the story of how humans have costumed themselves for extreme exploration. From the Mongolfiers’ balloon to Wiley Post and the high-altitude jump suit, you reveal some fascinating design precedents for the Apollo spacesuit—suggesting that it’s almost more of a technical outgrowth from the history of baroque costume design. Could you speak a little bit more about this background?

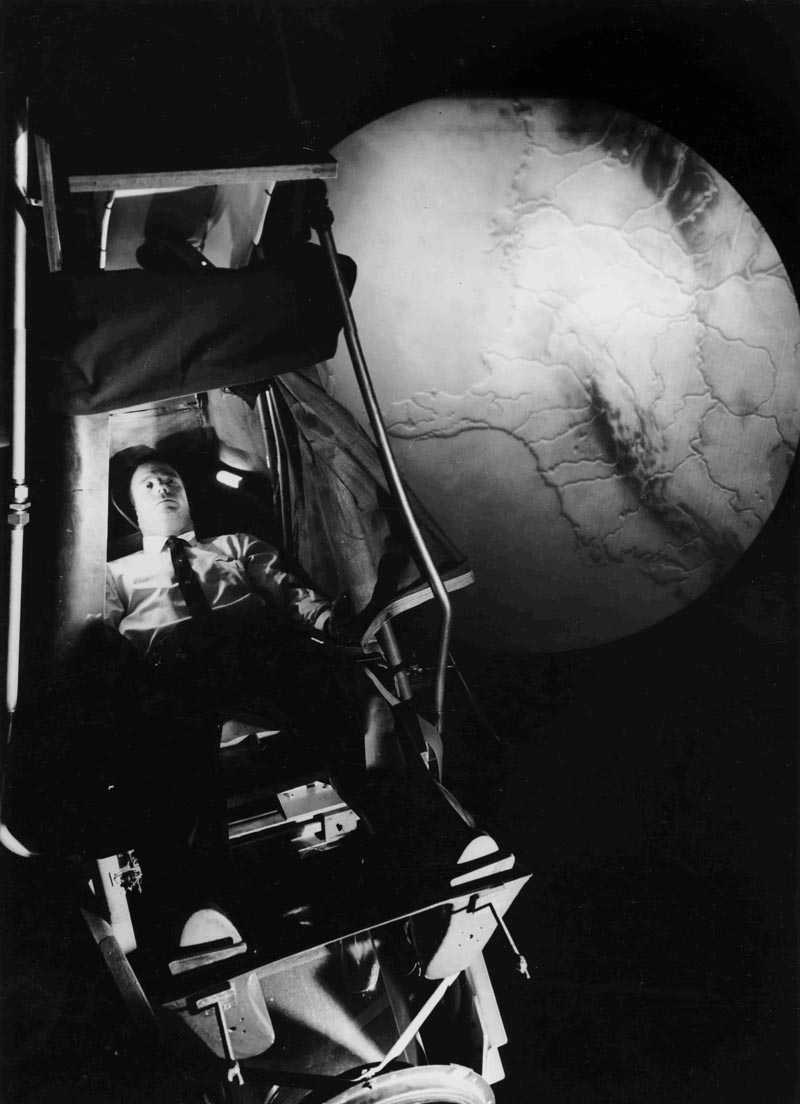

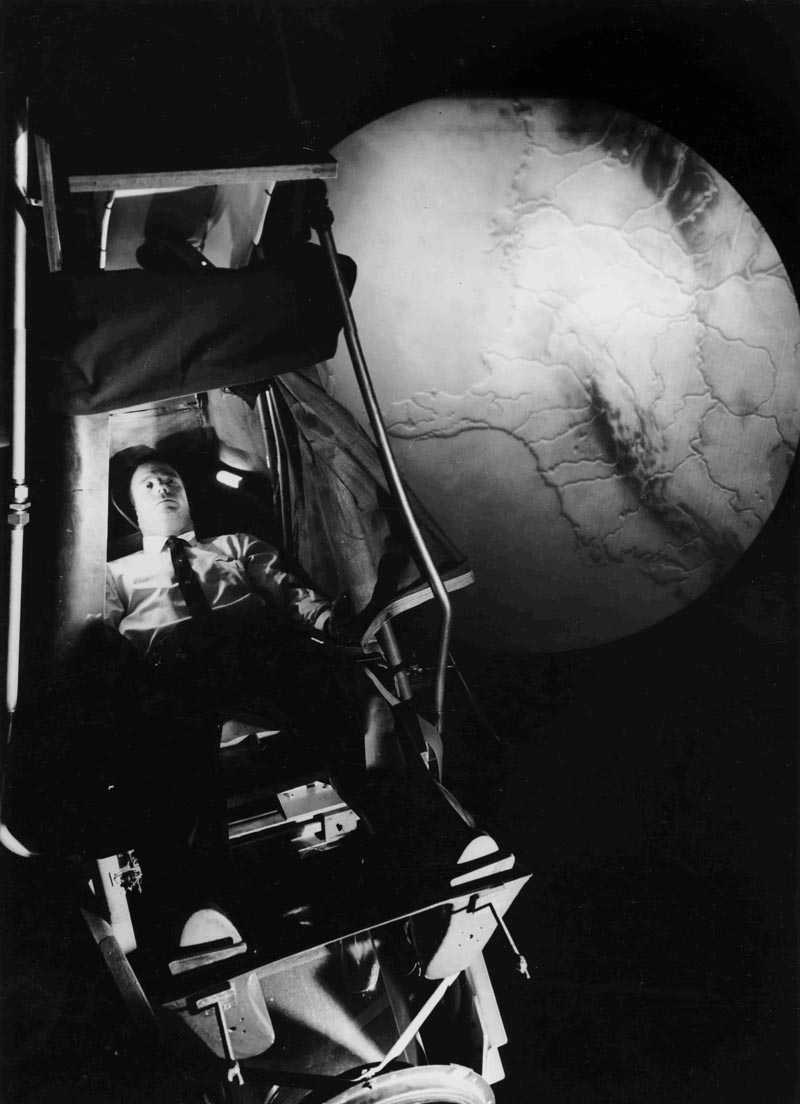

de Monchaux: One of the things I find most fascinating about the idea of the spacesuit is that space is actually a very complex and subtle idea. On the one hand, there is space as an environment outside of the earthly realm, which is inherently hostile to human occupation—and it was actually John Milton who first coined the term space in that context.

On the other hand, you have the space of the architect—and the space of outer space is actually the opposite of the space of the architect, because it is a space that humans cannot actually encounter without dying, and so must enter exclusively through a dependence on technological mediation.

Whether it’s the early French balloonists bringing capsules of breathable air with them or it’s the Mongolfier brothers trying to burn sheep dung to keep their vital airs alive in the early days of ballooning, up to the present day, space is actually defined as an environment to which we cannot be suited—that is to say, fit. Just like a business suit suits you to have a business meeting with a banker, a spacesuit suits you to enter this environment that is otherwise inhospitable to human occupation.

From that—the idea of suiting—you also get to the idea of fashion. Of course, this notion of the suited astronaut is an iconic and heroic figure, but there is actually some irony in that.

For instance, the word cyborg originated in the Apollo program, in a proposal by a psycho-pharmacologist and a cybernetic mathematician who conceived of this notion that the body itself could be, in their words, reengineered for space. They regarded the prospect of taking an earthly atmosphere with you into space, inside a capsule or a spacesuit, as very cumbersome and not befitting what they called the evolutionary progress of our triumphal entry into the inhospitable realm of outer space. The idea of the cyborg, then, is the apotheosis of certain utopian and dystopian ideas about the body and its transformation by technology, and it has its origins very much in the Apollo program.

But then the actual spacesuit—this 21-layered messy assemblage made by a bra company, using hand-stitched couture techniques—is kind of an anti-hero. It’s much more embarrassing, of course—it’s made by people who make women’s underwear—but, then, it’s also much more urbane. It’s a complex, multilayered assemblage that actually recapitulates the messy logic of our own bodies, rather than present us with the singular ideal of a cyborg or the hard, one-piece, military-industrial suits against which the Playtex suit was always competing.

The spacesuit, in the end, is an object that crystallizes a lot of ideas about who we are and what the nature of the human body may be—but, then, crucially, it’s also an object in which many centuries of ideas about the relationship of our bodies to technology are reflected.

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

BLDGBLOG: The spacesuit’s history implies a sort of David Bowie-like situation where astronauts are really cosmic cross-dressers—genderless and post-terrestrial, with no obligation to stay on Earth. But there are at least three different ways, I’d say, of preparing humans for inhospitable circumstances, whether that’s the moon, Antarctica, or Mars: one, you can turn humans into cyborgs, as you just explained; two, you can build them a spacesuit, which makes our ability to visit other planets a kind of unexpected outgrowth of the fashion industry; or, three, you can actually alter the atmosphere of the target destination itself, terraforming it, making it more Earth-like. It’s neither fashion nor architecture, but more like planetary-scale weather engineering.

de Monchaux: Well, I’d say that those are actually still two approaches. The cyborg approach and the climate-modification approach are not only one idea, conceptually, but they are also one and the same historically. The same individuals and organizations who were presuming to engineer the internal climate of the body and create the figure of the cyborg were the same institutions who, in the same context of the 1960s, were proposing major efforts in climate-modification.

Embedded in both of those ideas is the notion that we can reduce a complex, emergent system—whether it’s the body or the planet or something closer to the scale of the city—to a series of cybernetically inflected inputs, outputs, and controls. As Edward Teller remarked in the context of his own climate-engineering proposals, “to give the earth a thermostat.”

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious about other uses of spacesuit technology. For instance, biosafety suits allow humans to clean up after virological outbreaks or to enter Level 4 bioresearch labs without become infected—it’s clothing as quarantine, we might say. But there is also a different kind of space exploration, which is terrestrial exploration into the earth itself, through caving. The complex rebreathing apparatuses and wetsuits used in cave diving, in particular, are perhaps earthbound cousins of the Apollo spacesuit that you describe so well in the book.

de Monchaux: Absolutely. It’s the same notion. In the devices, mechanisms, and portable environments that we make for ourselves, and that we bring with us into these extreme situations, we see both the inconvenient truths and the convenient untruths of the relationships between technology and the body.

In the 1960s, which was a very anxious time in terms of the safety of the body, you have the image of the space traveler—but it was also an era of films like Fantastic Voyage where the human body itself was deemed to be this fantastic environment that we could enter using technologically mediated tools. And, in films like The Andromeda Strain, there’s that fabulous scene where the wall becomes the suit of the medical worker in quarantine. The architecture literally becomes a piece of clothing that you can wear.

In a sense, though, the diving suit is a fundamentally different technical project from a spacesuit. For instance, a diving suit has to protect against external compressive forces, whereas, in the spacesuit, it’s the internal expansion of a breathable atmosphere that the suit needs to hold in.

Other than that simple difference, though, the technologies end up being quite similar. For instance, the hard suits proposed by Litton Industries for use on the moon were never used, because, though they were conceptually very clear, they were logistically more cumbersome than the soft, mutable suits by Playtex. However, they ended up being adapted into a series of deep-sea diving suits—in fact, becoming the first jointed diving suits engineered in the 1960s.

Further, the same industrial division of Playtex that produced the Apollo spacesuit produces many of the suits used today by the EPA for major threat-level spills and contamination events, because the fundamental lessons about how to suit the body for these hostile environments are very similar.

As we’re discovering, we don’t have to go a quarter-million miles to the surface of the moon to discover environments that are inhospitable to the human body.

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

BLDGBLOG: On a more speculative level, your research implies, in a sense, that architects could simply design portable environments, in the form of elaborate, pressurized clothing and so on, instead of stationary structures called buildings. Put another way, is it no longer an avant-garde question to ask if clothing is the future of architecture?

de Monchaux: There are at least two levels at which that is very much true. An interesting history has yet to be written about the architectural influence of the Space Race. We’re used to understanding groups like Archigram and Coop Himmelb(l)au as being very influenced by inflatable environments and space habitats in the 1960s—and they truly were, and that’s a fascinating history. Even in the Soviet context, you see a kind of heroic architecture that springs directly out of the Space Race, such as the use of gigantic trusses and frames.

But if you look at American architectural magazines from the same era, you don’t see any of that at all. What you actually see is a kind of utopian vision of the systems-management that was at the core of NASA’s own technical approach, as if it could offer its own revolutionary hopes for architecture. In other words, there was something about the European perspective that seized on the actual, physical architectures of the American and Soviet space programs. For the American architectural psyche, the complex systems of the space race implied that any complex situation—cities, in particular—could be subject to principles of management.

This is interesting, especially as we see a return to the intimate as a zone for design in today’s architectural scene. We have many of the same anxieties and hopes now as were the case in the 1960s, when things like Michael Webb’s “Cushicle” first made their appearance. You only have to look at the work of someone like Hussein Chalayan, in fashion design, to see a vision of clothing itself embedded with sensors and actuators and HVAC and infrastructure, that recalls the complexity and function of a building more than anything like traditional clothing. And I would contrast this with the current architectural fascination for extending parametric systems to every scale.

As for the architecture of fabric more broadly, I think, as was the case in the Apollo program, fabric has a discourse of softness, protection, and layering that is very appropriate to our current architectural moment, despite the hard logic of systems that underlies much of what passes for fashion in architecture these days.

It’s also important to note that, in a world that is moving so fast, and in such uneasy and unsettling directions with issues such as climate change, peak oil, and the resilience of cities, that something like a clothing-based solution is probably more credible than parametrically designing whole future cities from scratch. Of course, as was pointed out by Walter Benjamin, fashion and the city have an intimate and particular relationship that I think is of clear relevance to this discussion.

I love the word fashion, by the way, because, on the one hand, it speaks to a kind of utter fabulousness that none of us, as designers, could live without; but, at the same time, fashion means to make something out of something else, often with a connotation that this is something it wasn’t originally intended for.

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

BLDGBLOG: The application of cybernetic and systems-based approaches to the management and administration of cities is also explored by another recent book—The Fires by Joe Flood. Flood’s book specifically looks at the limitations of cybernetic management as applied to firefighting in New York City. The failures of this era of city management seem increasingly of interest today, in fact, when places like New York now have “Chief Digital Officers” and so-called Smart Cities are all the rage. Your book seems, really, to be a prehistory for all this.

de Monchaux: When I presented the original lecture that turned into the Spacesuit book, I made a link between the spacesuit and the urban and environmental scale, mostly through what I would call a system of analogy; the body and the city have been talked about as models for each other at least since Vitruvius. Yet as I delved into the history of NASA, I discovered that what I had thought of initially as an analogy was, in fact, a dense web of historical and material connections.

In the book, I write about a figure named Harold Finger, who was, first, the director of research into nuclear propulsion for something called NACA, a predecessor of NASA. Finger did things like put the only nuclear reactor ever in an airplane—in a B-36 Peacemaker nuclear bomber. The windows to the cockpit needed to be 9-inch thick plexiglass to protect the pilots from radiation. You couldn’t make this stuff up! By 1962, the same figure—Finger—is designing long-range, nuclear-propelled, interplanetary spacecraft. He actually designed the spacecraft that Kubrick lifted and used as a model for the “Discovery” in 2001, with the nuclear reactor at one end, a long spur, and then a habitation module at the other end. And then he becomes NASA’s administrative director.

In 1968, though, he makes a shift to become the director of research for the Department of Housing and Urban Development. And this was not some unusual, crazy thing, where the director of research from NASA moves to HUD. This was very much the tenor of the time.

When Hubert Humphrey made his famous speech—where he said that the same techniques that got us to the moon would also solve the problems of American cities—he wasn’t operating by analogy. He was actually talking very explicitly about a direct transfer of techniques and ideas. You had this historical moment where there was a perceived crisis in the American city; you had the heroic victory of Apollo; and, of course, you then had the radical defunding of the space program. After all, the space program was only ever designed to produce a single TV image of an American man on the moon. In 1968, once they’d succeeded in doing that, you had all of the original engineers losing their jobs.

For instance, at Berkeley, where I teach, and also at MIT, there was a summer school in 1968 explicitly organized to train engineers who had been let go from NASA for new jobs in urban administration—for NASA engineers to become city managers. You can’t underestimate the extent to which this attempt to transfer the techniques of systems management from the national space program to cities was very self-conscious.

Also in 1968, for example, Jay Forrester wrote a book called Urban Dynamics, a very comprehensive cybernetic analysis of urban problems. Forrester was the guy who invented magnetic core memory—RAM—as well as early systems of computer networking for something called the semi-automatic ground environment, or SAGE, a nuclear defense system for the Air Force. And General Bernard Schriever, commander of the Air Force’s Western Development Division from 1954, developed systems engineering with Simon Ramo and Dean Wooldrige of what would become TRW; Neil Sheehan just wrote a marvelous biography of this moment in Schriever’s career. By 1968, Schriever was running a firm called Urban Systems Associates, or U.S.A. Simon Ramo also published his own book on applying systems engineering to urban problems in the same year, called Cure for Chaos.

Yet much like the attempts of the military-industrial complex to design, in the context of the space race, for the human body, most attempts to cybernetically optimize urban systems were spectacular failures, from which very few lessons seem to have been learned.

For instance, in our current architectural moment, our popular discourses of parametric urbanism and digital urban design seem to have been cut from the very same cloth. I was at the Parametric Urbanism conference at USC eighteen months ago and, just for my own amusement, I juxtaposed a series of quotations that came out of USC in a previous era, from a book written by a guy named Glen Swanson, who gave a symposium on the “Cybernetic Approach to Urban Analysis” in 1964.

If you lay, side by side, quotations from USC’s discourse on parametric urbanism now and USC’s discourse on cybernetic urbanism thirty years ago, for better or for worse, you can read them as a complete narrative. It’s impossible to distinguish which is which. Both are born out of a fundamental faith in technology and a fundamental notion that, if you feed enough variables into a problem-solving system—now we call it parametric, then we would have called it cybernetic—that an appropriate and robust solution will emerge. I’m not, myself, so sure that’s the case; in fact, I’m pretty certain that it’s not.

[Image: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Image: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious, then, how you’ll incorporate this criticism into your own Studio One program at Berkeley, which will include the use of parametric design tools as well as your own custom modeling software. How will you differentiate Studio One from the overtly technocratic approach that you just described, and what, in the end, is the ultimate goal for the studio?

de Monchaux: I wrote the Spacesuit book very much in the spirit of my own heroes and teachers—people like Alan Colquhoun, Liz Diller, and a whole generation of architects who were also theorists. They intended to figure out the meaning of the moment in which they found themselves, but then also to design for it. That means, of course, that I can’t just sit back and talk about these issues of technology and the city; I actually have to imagine what a constructive practice might be. That’s what I’ve focused on most in the past two to three years, and what has led to Studio One.

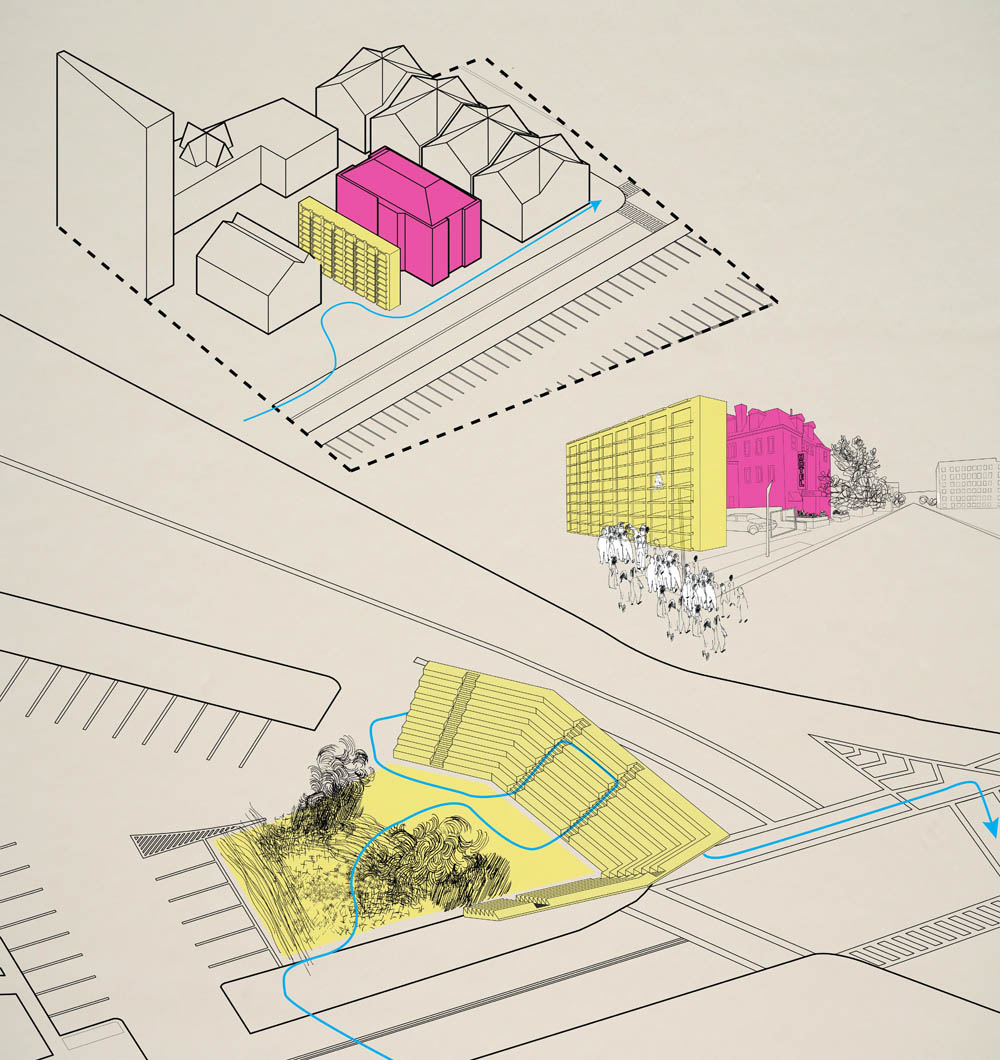

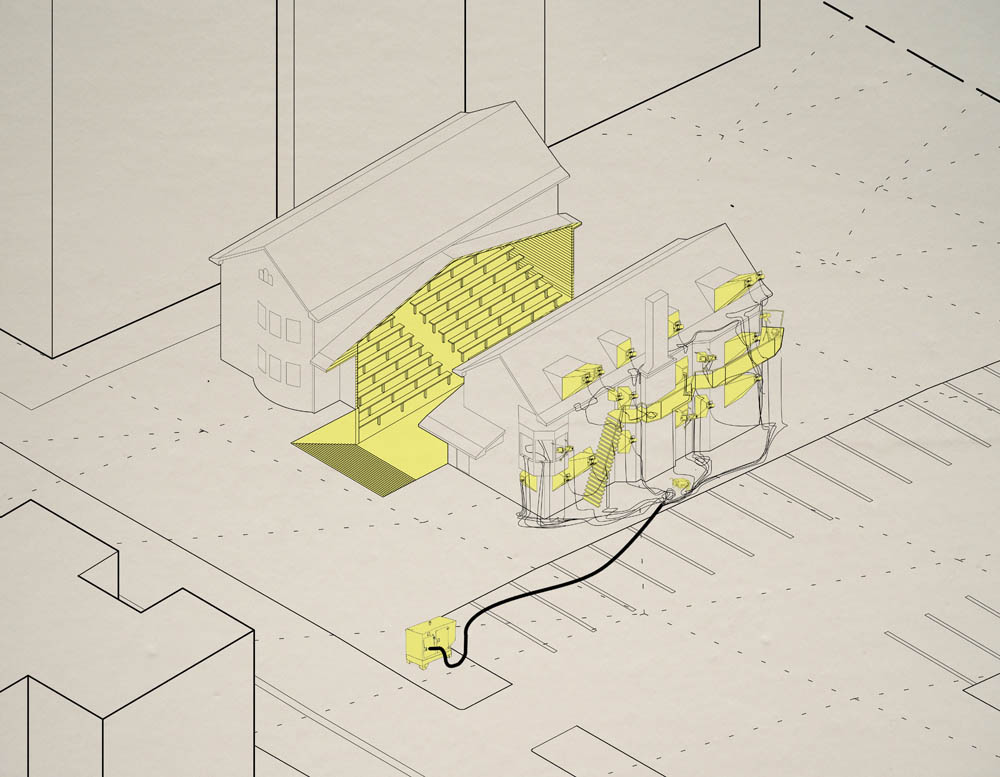

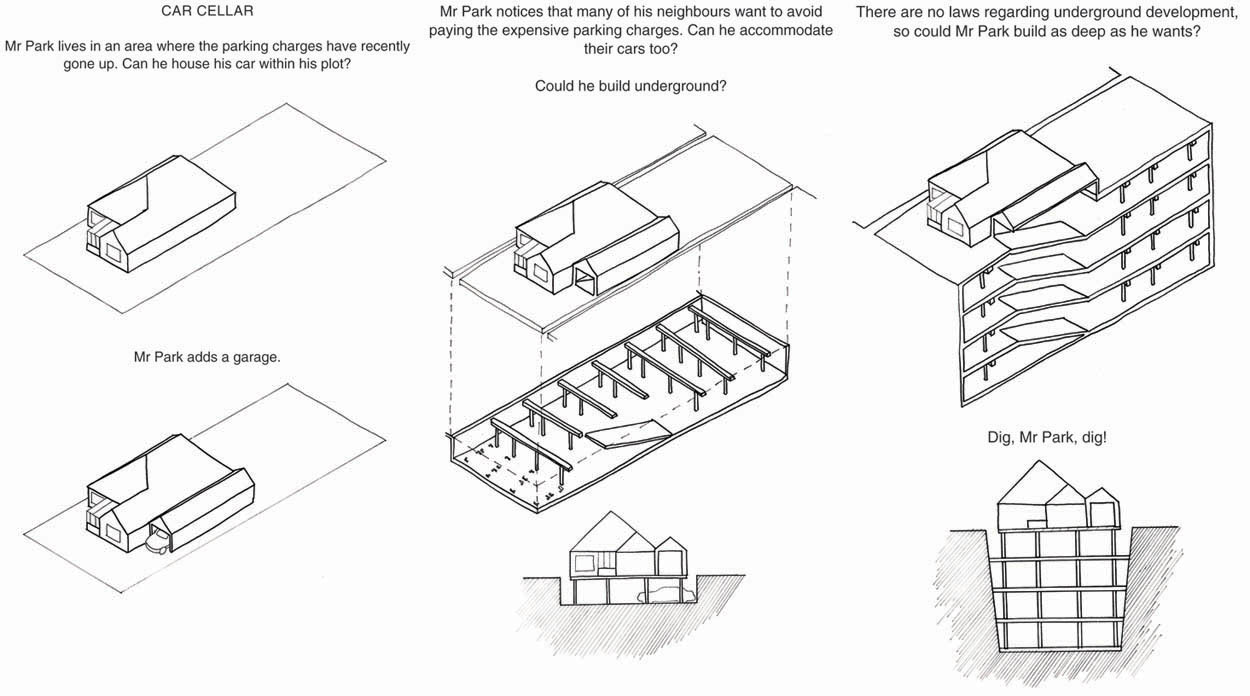

But the Studio One project really builds on the work that I’ve published as “Local Code.” I think one interesting point of intersection between them—and, I think, a shared interest with you—is the work of Gordon Matta-Clark. “Local Code” was very much a take on Matta-Clark’s “Fake Estates,” which was not actually conceived as a documentary project. Matta-Clark was interested, in the 1970s, in the kind of fissures and overlaps between the official and systematized vision of property assumed by the cadastral map and the actual nature of property on the ground.

One of the things I think is important about technology in the current moment is that it allows us ever more completely to visualize and very precisely map the fissures between a technologically mediated understanding of the world and the world as it actually is—and then to exploit those fissures as designers.

A bit like my stumbling on the links between the space race and the urban history of the late 1960s, when I went into the “Local Code” project, I thought that “Fake Estates” was just a great analogy. Now, though, you can find 5,000 sites in New York instead of 15, and you can even figure out, parametrically, what to do with them and how to turn them into an ecological resource. But then, when I went into the history, it turns out that, by 1975-77, Matta-Clark was deeply excited about the prospects of computing and digital mapping, and he had conceived a whole project using left-over urban space—in his case, I kid you not, for a whole series of what he called “pneumatic network enclosures” that would have provided resources to underprivileged neighborhoods.

So we can look to his practice not just as a kind of analogical inspiration but, more literally, as an interesting alternative model for architecture: that architecture can be informed by technology and, at the same time, avoid what I view as the dead-end of an algorithmically inflected formalism from which many of the, to my mind, less convincing examples of contemporary practice have emerged.

I’m actually speaking to you right now from the Autodesk office in downtown San Francisco. I don’t know if you can see the Ferry Building over my shoulder [N.b. picks up laptop and angles camera outside the window toward the Ferry Building], but they’ve invited us to do a residency here and to complete the parametric design of the 5,000 leftover spaces in New York that we’ve identified. We’ll have that project going on all spring here, hoping to publish it this summer.

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

BLDGBLOG: I would love to see the non-urban equivalent of this project. In other words, it would be fascinating to see what scraps of land, in extremely rural areas, also fall into these sorts of federal, municipal, and even just gerrymandered blindspots. Spatial fissures, as you call them, can be just as complex outside the context of, say, downtown San Francisco or Manhattan.

de Monchaux: Of course! The modernist notion that the world needs to be perfect is something that is so fundamental to how architects think about design, yet so potentially problematic in its actual application. Matta-Clark said very directly that “the availability of leftover and unplanned space is one of the primary critiques of progress through modernization.”

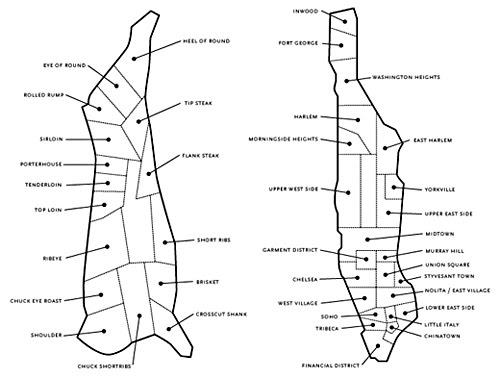

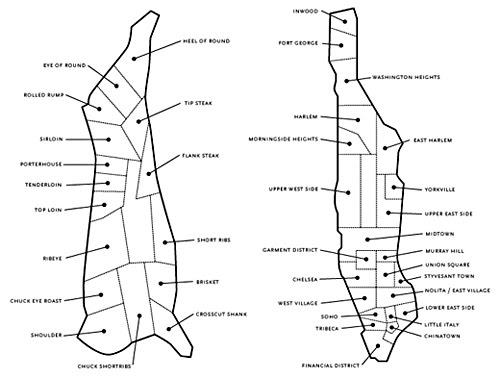

[Image: From “Meatropolis” by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Image: From “Meatropolis” by Nicholas de Monchaux].

BLDGBLOG: One other aspect of your work that I want to touch on briefly is an essay of yours called “Meatropolis,” on food and the city—in particular, on meat and Manhattan. I’d love to hear more about your research into how urban form can be seen as a graph of shifting consumption practices.

de Monchaux: Many people have looked at the history of the city and meat, of course, but that paper was my attempt to see how and whether there was any further truth behind the formal resonance. In the case of my essay, I showed the butcher diagram of a cow and a map of all the neighborhoods of Manhattan—and they do look fairly similar—but the essay tries to examine whether there’s anything more to that superficial similarity.

And, in my mind, there actually is. In both cases, you have complex tissue reduced to a simplified diagram for the sake of its consumption. But we confuse the butchering diagram with the cow, and the neighborhood diagram with the city, at our peril. That’s a highly consumptive and highly simplistic lens—the lens of neighborhoods, the lens of cuts of meat.

Robert Moses once said that, in order to make the city work, you have to cut through it with a meat axe—but it turns out the city has a whole complex set of tissues and connections that are, in Jane Jacobs’s words, inherently irreducible to diagrams. They are, in her words, as slippery as an eel—to use another food metaphor.

I think that, between those two, you have a really interesting space. One of the other historical connections that turned up in my own work is between the early writing of Jane Jacobs, in the case of Death and Life of Great American Cities, and the early research done in the 1950s and 60s on complexity and emergence under the aegis of the Rockefeller Foundation. The Rockefeller Foundation not only funded Jacobs’s work to the tune of about $5,000 in 1962, which was a lot of money back then, but also gave her office space with the then-president of the Rockefeller Foundation, Warren Weaver. Weaver was a seminal founding figure of complexity science, and was, in fact, the first to coin the phrase “the science of organized complexity”—this notion that our attempts at measurement both freeze and oversimplify something fundamental to natural systems at every scale, from our own body to the city, upward to the ecology of the planet as a whole.

Interestingly, just to bring it full-circle, when I gave my spacesuit lecture at the Santa Fe Institute in 2003, the notion that the city itself should essentially be seen as a complex system was something that people took for granted, but it didn’t have a lot to do with the work that was going on there in complex systems and emergence.

Since that time, however, in the last couple of years, I’ve been engaged with the work of two scientists at the Institute—Geoffrey West and Luis Bettencourt—who have gone a long way in showing that, not only should cities be viewed through the analogical lens of complex natural systems, but, in fact, some of the mathematics—in particular, to do with scaling laws, the consumption of resources, and the production of innovation by cities—proves itself far more susceptible to analyses that have come out of biology than, say, conventional economics.

And at the same time, current work in more conventional biology—for example, with the internal biome and ecology of our bodies, where bacterial cells outnumber our own cells by 10 to 1—uses economic and statistical techniques developed to understand cities.

So, without falling too far into sensationalism, we’re getting really interesting indications that intuitions by anyone flying in an airplane at night—that cities look like amoebae or giant life forms—might be a lot closer to the truth than we’ve ever had a chance to understand before, both in the sense that they have their own kind of biology and that organisms are turning out to have their own kind of urbane, material economy.

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Images: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

BLDGBLOG: Even the design tools and software packages that we use often have surprising and unexpected connections across disciplines, from urban mapping to missile guidance and from cancer research to special effects. Software archaeology becomes really interesting, in this context—looking at the shared codes and subroutines of otherwise very different software programs. For instance, Auto-Tune, which is now used on basically every pop record, was actually designed as a seismic-analysis tool for Exxon, to find underground oil deposits. My point is that many, seemingly unrelated disciplines can actually have a lively and engaged conversation together simply on the level of shared research tools.

de Monchaux: Yes. For instance, it’s become fashionable—probably rightly so—to talk about the formal and analogical links between the technological systems and media by which we design today and the midcentury systems of the military-industrial complex. But I didn’t fully realize, for instance, how much of the CAD system that I’m sitting in front of right now here at Autodesk, or the GIS technologies that I make use of in the office, come out of very direct historical and material connections.

For instance, not only is the GIS software that I used to make “Local Code” like the software that was developed to target defensive nuclear missiles; it, in many ways, is that system. It shares code with it; it shares conceptual and algorithmic approaches with it, including the projection of cartographic information onto screens in an interactive way.

As designers, we stand much more shoulder-to-shoulder with the missile-men and systems engineers of midcentury than we might even feel comfortable with, in terms of the tools that we’re increasingly using to shape the physical world.

An awareness of the true nature of those tools is essential, I think, for us to unlock their actual, potentially liberating possibilities; knowing their origins, you can be much more strategic in your relationship to that history, and use these tools not as they were intended to be used—or even directly as they weren’t intended to be used—but from more oblique perspectives, more uncanny angles of incidence. It’s in this territory, I think, that much more essential and interesting architectural research needs to be done.

• • • [Image: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

[Image: From Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo by Nicholas de Monchaux].

Thanks again to Nicholas de Monchaux for having this conversation! For more, pick up a copy of his book, about which you can read more at its website, Fashioning Apollo.

[Image: Michael Maltzan’s Inner City Arts building, Los Angeles; photo by Iwan Baan].

[Image: Michael Maltzan’s Inner City Arts building, Los Angeles; photo by Iwan Baan]. [Image: Los Angeles; photo by Iwan Baan, from No More Play].

[Image: Los Angeles; photo by Iwan Baan, from No More Play]. [Image: Los Angeles; photo by Iwan Baan, from No More Play].

[Image: Los Angeles; photo by Iwan Baan, from No More Play].

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

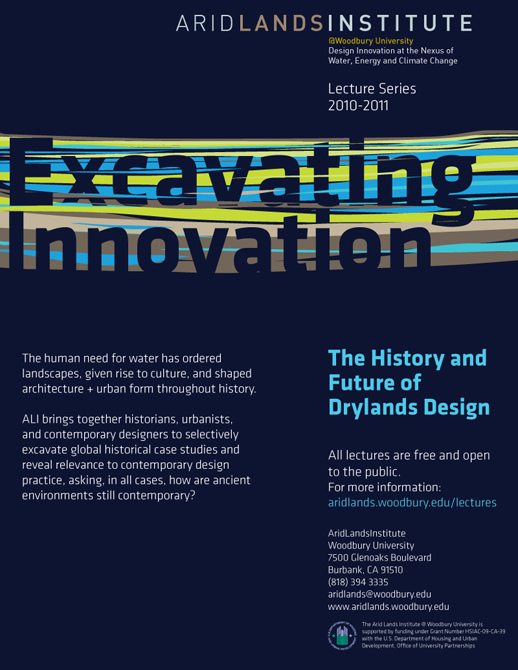

If I could go back in time, there are two things I would have prioritized this autumn, had I known about them earlier: 1) I would have stopped by the

If I could go back in time, there are two things I would have prioritized this autumn, had I known about them earlier: 1) I would have stopped by the  Here’s a description of the lecture series:

Here’s a description of the lecture series:

The specific lectures sound almost too good to be true, including a forthcoming talk this Thursday, November 18, about the stepwells of India—fantastically gorgeous native hydrological structures I’ve returned to again and again in my own off-blog reading and research.

The specific lectures sound almost too good to be true, including a forthcoming talk this Thursday, November 18, about the stepwells of India—fantastically gorgeous native hydrological structures I’ve returned to again and again in my own off-blog reading and research.  [Image: Stepwell at Chand Baori, courtesy of

[Image: Stepwell at Chand Baori, courtesy of

[Image: The Holland Tunnel Land Ventilation Building, courtesy of

[Image: The Holland Tunnel Land Ventilation Building, courtesy of

[Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: From Gordon Matta-Clark’s

[Image: From Gordon Matta-Clark’s

[Image: “The Dormant Workshop” by

[Image: “The Dormant Workshop” by  [Image: “Log Harvest 2041” by

[Image: “Log Harvest 2041” by  [Image: “Reforestation of the Thames Estuary” by

[Image: “Reforestation of the Thames Estuary” by  [Image: “Lecture Preparations” by

[Image: “Lecture Preparations” by  [Image: “Urban Nature” by

[Image: “Urban Nature” by  [Image: “Timber Craft Workshop” by

[Image: “Timber Craft Workshop” by  [Image: “Thames Revival” by

[Image: “Thames Revival” by

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Images: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Images: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the  [Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the  [Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the  [Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Images: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Images: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Image: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams]. [Images: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Images: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams]. [Image: An awesome glimpse of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of

[Image: An awesome glimpse of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of  [Images: Another mind-bending example of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of

[Images: Another mind-bending example of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of