I first discovered Mike Davis’s work about a decade ago, through his book City of Quartz, a detailed and poetic look at the social geography of Los Angeles. Perhaps most memorably, City of Quartz describes the militarization of public space in LA, from the impenetrable “panic rooms” of Beverly Hills mansions to the shifting ganglands of South Central. Not only does the Los Angeles Police Department use “a geo-synchronous law enforcement satellite” in their literal oversight of the city, but “thousands of residential rooftops have been painted with identifying street numbers, transforming the aerial view of the city into a huge police grid.” In Los Angeles today, “carceral structures have become the new frontier of public architecture.”

A more wide-ranging book is Davis’s 2002 collection Dead Cities. The book ends with an invigorating bang: its final section, called “Extreme Science,” is a perfect example of how Davis’s work remains so consistently interesting. We come across asteroid impacts, prehistoric mass extinctions, Victorian disaster fiction, planetary gravitational imbalances, and even the coming regime of human-induced climate change, all in a book ostensibly dedicated to West Coast American urbanism.

Of course, Mike Davis’s particular breed of urban sociology has found many detractors – detractors who accuse Davis of falsifying his interviews, performing selective research, deliberately amplifying LA’s dark side (whether that means plate tectonics, police brutality, or race riots), and otherwise falling prey to battles in which Davis’s classically Marxist approach seems both inadequate and outdated. In fact, these criticisms are all justified in their own ways – yet I still find myself genuinely excited whenever a new book of his hits the bookshop display tables.

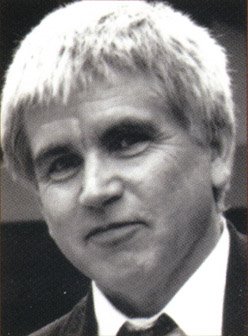

In any case, the following interview took place after the publication of Davis’s most recent book, Planet of Slums. Having reviewed that book for the Summer 2006 issue of David Haskell’s Urban Design Review, I won’t dwell on it at length here; but Planet of Slums states its subject matter boldy, on page one. There, Davis writes that we are now at “a watershed in human history, comparable to the Neolithic or Industrial revolutions. For the first time the urban population of the earth will outnumber the rural.”

This “urban” population will not find its home inside cities, however, but deep within horrific mega-slums where masked riot police, raw human sewage, toxic metal-plating industries, and emerging diseases all violently co-exist with literally billions of people. Planet of Slums quickly begins to read like some Boschian catalog of our era’s most nightmarish consequences. The future, to put it non-judgmentally, will be interesting indeed.

Mike Davis and I spoke via telephone.

•BLDGBLOG:

First, could you tell me a bit about the actual writing process of Planet of Slums? Was there any travel involved?

Davis: This was almost entirely an armchair journey. What I tried to do was read as much of the current literature on urban poverty, in English, as I could. Having four children, two of them toddlers, I only wish I could visit some of these places. On the other hand, I write from our porch, with a clear view of Tijuana, a city I know fairly well, and that’s influenced a lot of my thinking about these issues – although I tried scrupulously to avoid putting any personal journalism into the narrative.

Really, the book is just an attempt to critically survey and synthesize the literature on global urban poverty, and to expand on this extraordinarily important report of the United Nations – The Challenge of Slums – which came out a few years ago.

BLDGBLOG: So you didn’t visit the places you describe?

Davis: Well, I was initially anticipating writing a much longer book, but when I came to what should have been the second half of Planet of Slums – which looks at the politics of the slum – it became just impossible to rely on secondary or specialist literature. I’m now collaborating on a second volume with a young guy named Forrest Hylton, who’s lived for several years in Colombia and Bolivia. I think his first-hand experience and knowledge makes up for most of my deficiencies, and he and I are now producing the second book.

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious about the vocabulary that you use to describe this new “post-urban geography” of global slums: regional corridors, polycentric webs, diffuse urbanism, etc. I’m wondering if you’ve found any consistent forms or structures now arising, as cities turn away from centralized, geographically obvious locations, becoming fractal, slum-like sprawl.

Davis: First of all, the language with which we talk about metropolitan entities and larger-scale urban systems is already eclectic because urban geographers avidly debate these issues. I think there’s little consensus at all about the morphology of what lies beyond the classical city.

The most important debates really arose through discussions of urbanization in southern China, Indonesia, and southeast Asia – and that was about the nature of peri-urbanization on the dynamic periphery of large Third World cities.

BLDGBLOG: And “peri-urbanization” means what?

Davis: It’s where the city and the countryside interpenetrate. The question is: are you, in fact, looking at a snapshot of a very dynamic or perhaps chaotic process? Or will this kind of hybrid quality be preserved over any length of time? These are really open questions.

There are several different discussions here: one on larger-order urban systems – similar to the Atlantic seaboard or Tokyo-Yokohama, where metropolitan areas are linked in continuous physical systems. But then there’s this second debate about the spill-over into the countryside, this new peri-urban reality, where you have very complex mixtures of slums – of poverty – crossed with dumping grounds for people expelled from the center – refugees. Yet amidst all this you have small, middle class enclaves, often new and often gated. You find rural laborers trapped by urban sweatshops, at the same time that urban settlers commute to work in agricultural industries.

This, in a way, is the most interesting – and least-understood – dynamic of global urbanization. As I try to explain in Planet of Slums, peri-urbanism exists in a kind of epistemological fog because it’s not well-studied. The census data and social statistics are notoriously incomplete.

BLDGBLOG: So it’s more a question of how to study the slums – who and what to ask, and how to interpret that data? Where to get your funding from?

Davis: At the very least, it’s a challenge of information. Interestingly, this has also become the terrain of a lot of Pentagon thinking about urban warfare. These non-hierarchical, labyrinthine peripheries are what many Pentagon thinkers have fastened onto as one of the most challenging terrains for future wars and other imperial projects. I mean, after a period in which the Pentagon was besotted with trendy management theory – using analogies with Wal-Mart and just-in-time inventory – it now seems to have become obsessed with urban theory – with architecture and city planning. This is happening particularly through things like the RAND Corporation’s Arroyo Center, in Santa Monica.

The U.S. has such an extraordinary ability to destroy hierarchical urban systems, to take out centralized urban structures, but it has had no success in the Sadr Cities of the world.

BLDGBLOG: I don’t know – they leveled Fallujah, using tank-mounted bulldozers and Daisy Cutter bombs –

Davis: But the city was soon re-inhabited by the same insurgents they tried to force out. I think the slum is universally recognized by military planners today as a challenge. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if there’s a great leap forward in our understanding of what’s happening on the peripheries of Third World cities because of the needs of Pentagon strategists and local military planners. For instance, Andean anthropology made a big leap forward in the 1960s and early 1970s when Che Guevara and his guerilla fighters became a problem.

I think there’s a consensus, both on the left and the right, that it’s the slum peripheries of poor Third World cities that have become a decisive geopolitical space. That space is now a military challenge – as much as it is an epistemological challenge, both for sociologists and for military planners.

BLDGBLOG: What kind of imaginative role do you see slums playing today? On the one hand, there’s a kind of CIA-inspired vision of irrational anti-Americanism, mere breeding grounds for terrorism; on the other, you find books like The Constant Gardener, in which the Third World poor are portrayed as innocent, naive, and totally unthreatening, patiently awaiting their liberal salvation. Whose imaginination is it in which these fantasies play out?

Davis: I think, actually, that if Blade Runner was once the imaginative icon of our urban future, then the Blade Runner of this generation is Black Hawk Down – a movie I must admit I’m drawn to to see again and again. Just the choreography of it – the staging of it – is stunning. But I think that film really is the cinematic icon for this new frontier of civilization: the “white man’s burden” of the urban slum and its videogame-like menacing armies, with their RPGs in hand, battling heroic techno-warriors and Delta Force Army Rangers. It’s a profound military fantasy. I don’t think any movie since The Sands of Iwo Jima has enlisted more kids in the Marines than Black Hawk Down. In a moral sense, of course, it’s a terrifying film, because it’s an arcade game – and who could possibly count all the Somalis that are killed?

BLDGBLOG: It’s even filmed like a first-person shooter. Several times you’re actually watching from right behind the gun.

Davis: It’s by Ridley Scott, isn’t it?

BLDGBLOG: Yeah – which is interesting, because he also directed Blade Runner.

Davis: Exactly. And he did Black Rain, didn’t he?

BLDGBLOG: The cryptic threat of late-1980s Japan…

Davis: Ridley Scott – more than anyone in Hollywood – has really defined the alien Other.

Of course, in reality, it’s not white guys in the Rangers who make up most of the military presence overseas: it’s mostly slum kids themselves, from American inner cities. The new imperialism – like the old imperialism – has this advantage, that the metropolis itself is so violent, with such concentrated poverty, that it produces excellent warriors for these far-flung military campaigns. I remember reading a brilliant book once by a former professor of mine, at the University of Edinburgh, on British imperial warfare in the nineteenth century. He showed, against every expectation, that, in fact, most often for the British Army, in imperial wars, what was decisive wasn’t their possession of better weapons, or artillery, or Maxim guns: it was the ability of the British soldier to engage in personal carnage, hand-to-hand combat, up close with bayonets – and that was strictly a function of the brutality of life in British slums.

Now, if you read the literature on warfare today, this is what the Pentagon’s really capitalizing on: they’re using the American inner city as a kind of combat laboratory, in addition to these urban test ranges they’ve built to study their new technologies. The slum dwellers’ response to this, and it’s a response that has yet to be answered – and maybe it’s unanswerable – is the poor man’s Air Force: the car bomb. That’s the subject of another book I’m finishing up right now, a short history of the car bomb. That has to be one of the most decisive military innovations of the late twentieth century. If you look at what’s happening in Iraq, it may be the Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) that are killing Americans, but what’s just ripping that country apart is these fortified car bomb attacks. The car bomb has given poor people in slums – small groups and networks – a new, extremely traumatic kind of geopolitical leverage.

What’s happened, I think, at the end of the 20th century – and at the beginning of the 21st – is that the outcasts have discovered these extraordinarily cheap and horrific weapons. That’s why I argue, in Planet of Slums, that they have “the gods of chaos” on their side.

BLDGBLOG: Beyond a turn toward violence and insurgency, do you see any intentional, organized systems of self-government emerging in the slums? Is there a slum “mayor,” for instance, or a kind of slum city hall? In other words, who would a non-military power negotiate with in the first place?

Davis: Organization in the slums is, of course, extraordinarily diverse. The subject of the second book – that I’m writing with Forrest Hylton – will be what kinds of trends and unities exist within that diversity. Because in the same city – for instance, in a large Latin American city – you’ll find everything from Pentacostal churches to the Sendero Luminoso, to reformist organizations and neoliberal NGOs. Over very short periods of time there are rapid swings in popularity from one to the other – and back. It’s very difficult to find a directionality in that, or to predict where things might go.

But what is clear, over the last decade, is that the poor – and not just the poor in classical urban neighborhoods, but the poor who, for a long time, have been organized in leftwing parties, or religious groups, or populist parties – this new poor, on the fringes of the city, have been organizing themselves massively over the last decade. You have to be struck by both the number and the political importance of some of these emerging movements, whether that’s Sadr, in Iraq, or an equivalent slum-based social movement in Buenos Aires. Clearly, in the last decade, there have been dramatic increases in the organization of the urban poor, who are making new and, in some cases, unprecedented demands for political and economic participation. And where they are totally excluded, they make their voices heard in other ways.

BLDGBLOG: Like using car bombs?

Davis: I mean taking steps toward formal democracy. Because the other part of your question concerns the politics of poor cities. I’m sure that somebody could write a book arguing that one of the great developments of the last ten or fifteen years has been increased democratization in many cities. For instance, in cities that did not have consolidated governments, or where mayors were appointed by a central administration, you now have elections, and elected mayors – like in Mexico City.

What’s so striking, in almost all of these cases, is that even where there’s increased formal democracy – where more people are voting – those votes actually have little consequence. That’s for two reasons: one is because the fiscal systems of big cities in the Third World are, with few exceptions, so regressive and corrupt, with so few resources, that it’s almost impossible to redistribute those resources to voting people. The second reason is that, in so many cities – India is a great example of this – when you have more populist or participatory elections, the real power is simply transferred into executive agencies, industrial authorities, and development authorities of all kinds, which tend to be local vehicles for World Bank investment. Those agencies are almost entirely out of the control of the local people. They may even be appointed by the state or by a provisional – sometimes national – government.

This means that the democratic path to control over cities – and, above all, control over resources for urban reform – remains incredibly elusive in most places.

(This interview continues in Part Two. For another, recent two-part interview with Mike Davis, see TomDispatch: Part 1, Part 2. All drawings used in this interview are by Leah Beeferman, who was also behind BLDGBLOG’s Helicopter Archipelago).

I’m immensely pleased to announce BLDGBLOG’s first event, on January 13th in Los Angeles, to be hosted by the Center for Land Use Interpretation.

I’m immensely pleased to announce BLDGBLOG’s first event, on January 13th in Los Angeles, to be hosted by the Center for Land Use Interpretation. Back in 1997, then, I found myself in Rotterdam where I went to the Netherlands Architecture Institute several days in a row to use their architecture library; the NAi’s exhibit at the time was about Daniel Libeskind. While this proves that I’m possibly the world’s lamest backpacker, it also resulted in my stumbling across a copy of Mary-Ann Ray’s Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice, and Midgets, a book I highly recommend to just about anyone – and a book that may or may not even be responsible for my current interest in architecture.

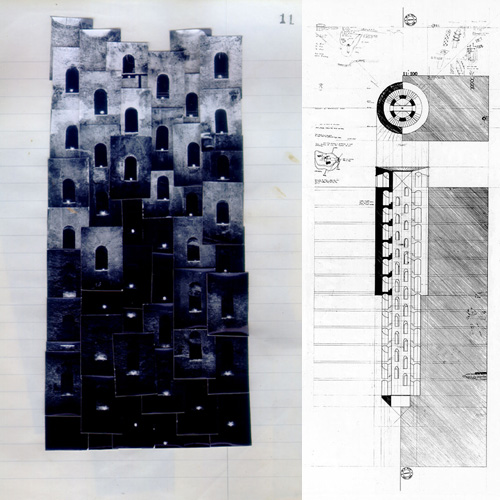

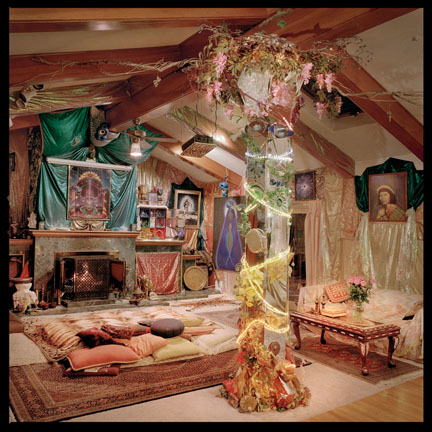

Back in 1997, then, I found myself in Rotterdam where I went to the Netherlands Architecture Institute several days in a row to use their architecture library; the NAi’s exhibit at the time was about Daniel Libeskind. While this proves that I’m possibly the world’s lamest backpacker, it also resulted in my stumbling across a copy of Mary-Ann Ray’s Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice, and Midgets, a book I highly recommend to just about anyone – and a book that may or may not even be responsible for my current interest in architecture.  [Image: Mary-Ann Ray, from Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice, and Midgets].

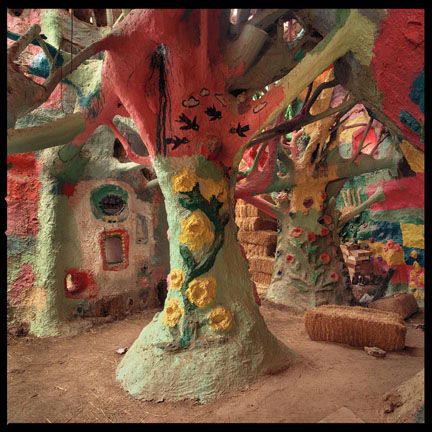

[Image: Mary-Ann Ray, from Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice, and Midgets]. [Image: From Robert Sumrell’s Portfolio 4].

[Image: From Robert Sumrell’s Portfolio 4]. [Image: An example of “mega coral,” crocheted by Christine Wertheim].

[Image: An example of “mega coral,” crocheted by Christine Wertheim]. [Image: Part of Shea Zellweger’s logical alphabet; image courtesy of Shea Zellweger, via the Institute for Figuring].

[Image: Part of Shea Zellweger’s logical alphabet; image courtesy of Shea Zellweger, via the Institute for Figuring]. [Image:

[Image:  [Image: A passing Illinois lightning storm and supercell, the clouds peeling away to reveal evening stars; photo ©

[Image: A passing Illinois lightning storm and supercell, the clouds peeling away to reveal evening stars; photo ©

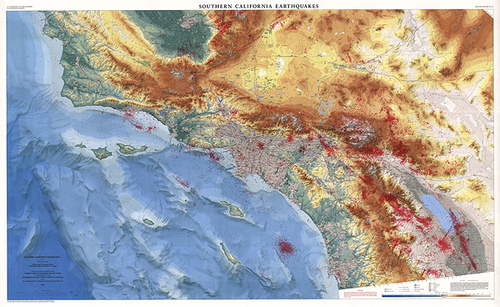

[Image: USGS Map of

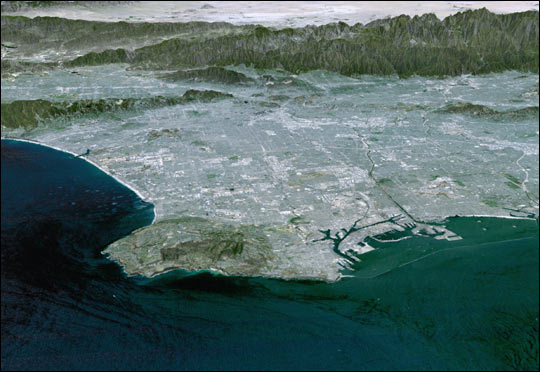

[Image: USGS Map of  [Image: Octopus L.A. For the more satellite-inclined, check out

[Image: Octopus L.A. For the more satellite-inclined, check out

[Image: J.M. Gandy, speculations toward the ruins of John Soane’s Bank of England – but, again, how about speculations toward the Bank of England’s fossils…?]

[Image: J.M. Gandy, speculations toward the ruins of John Soane’s Bank of England – but, again, how about speculations toward the Bank of England’s fossils…?]