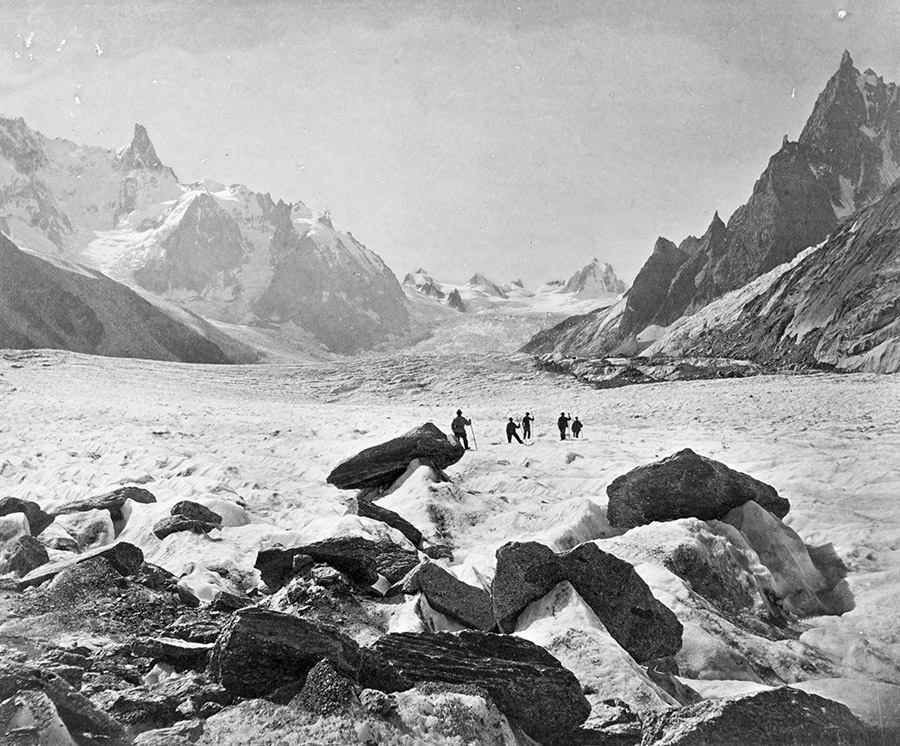

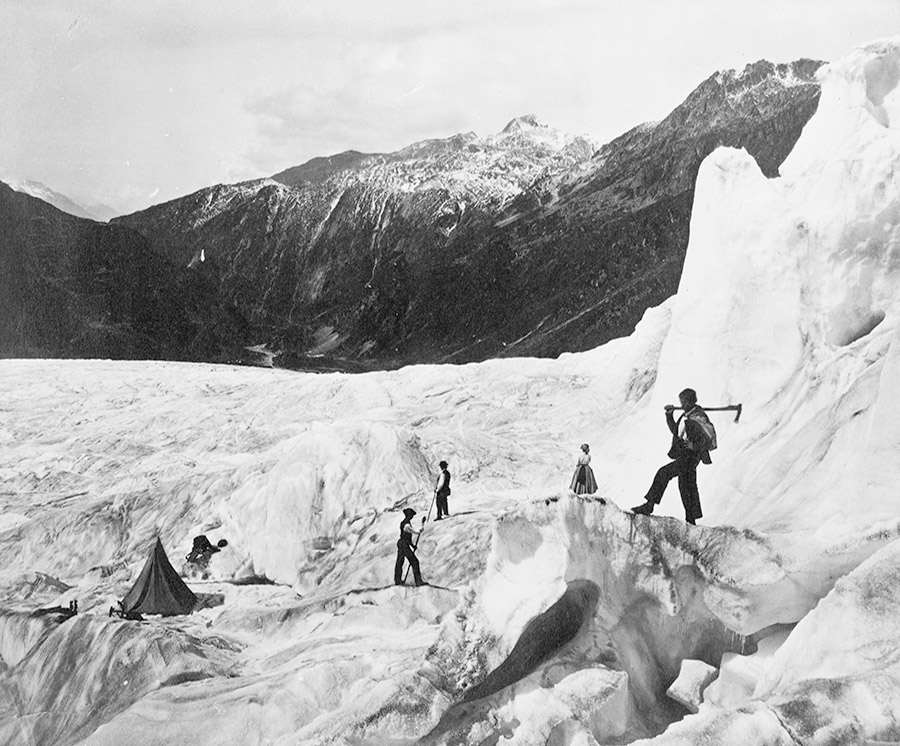

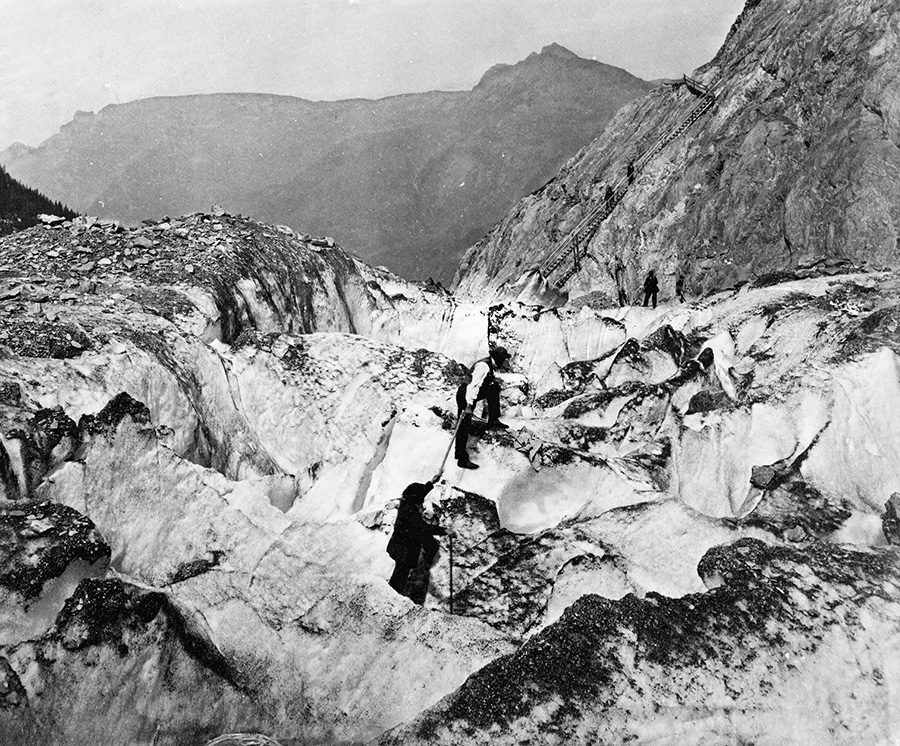

[Image: Photo by Gerco de Ruijter, via but does it float].

[Image: Photo by Gerco de Ruijter, via but does it float].

A short article by Sam Kean for the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia explores the world of “bizarro ice—ice that burns, ice that sinks instead of floating, ice literally out of this world.” For the most part, these are ices that have formed under extraordinary pressure, whether naturally or artificially applied, which “forc[es] H2O molecules into rhombuses, tetragons, and other alternative geometries.”

In some cases, the pressure is so great that the resulting ice “can stay solid at temperatures of thousands of degrees—a true freezer burn. If you could somehow plop chunks of these ices into a glass of liquid water, they’d vaporize it.” Incredibly, we read that, “at super-high pressures, some chemists predict that ice transforms into a metal.”

There is an ice “that’s structurally similar to diamonds,” Kean explains, that “probably exists in the upper atmosphere.” And there are exotic ices on other planets: “The dense, hot interiors of Neptune and Uranus probably contain chunks of nonhexagonal ices, as do exoplanets around distant stars, a potentially important consideration as we search for life beyond our solar system.”

[Image: The Sea of Ice by Caspar David Friedrich].

[Image: The Sea of Ice by Caspar David Friedrich].

This latter remark brings to mind a book I downloaded in my recent PDF binge called The Science of Solar System Ices, edited by Murthy S. Gudipati and Julie Castillo-Rogez. It’s a mammoth book—more than 650 pages—that explores exotic ices found in comets, on exoplanets, on moons, and elsewhere in our solar system.

“The largest deposits of carbon dioxide ice,” we learn, “is on Mars. Sulfur dioxide ice is found in the Jupiter system. Nitrogen and methane ices are common beyond the Uranian system. Saturn’s moon Titan probably has the most complex active chemistry involving ices, with benzene and many tentative or inferred compounds,” including a long list of chemicals I can’t even pronounce let alone recognize or describe, forming ices with “unusual colors and spectral shapes.” There are even “organic” ices made of hydrocarbons.

[Image: The Monk by the Sea by Caspar David Friedrich].

[Image: The Monk by the Sea by Caspar David Friedrich].

How these ices produce landscapes is by far the most interesting aspect here, at least from the point of view of BLDGBLOG: how they glaciate, experience gravitational tides and weathering, melt from below due to volcanoes, reflect the alien skies shining down on them in distorted shapes and angled echoes, and even how they tectonically fracture into karst-like networks of sinkholes and caves.

Imagining snow storms of frozen methane on other planets while thinking about, for example, human artistic traditions of landscape representation, from the Hudson Valley School to Caspar David Friedrich—picturing massive and extraordinary widescreen scenes of glacial hills and valleys steaming in the outer darkness of the solar system and the paintings or photographs or even animated GIFs that might result—would extend the idea of the sublime to non-terrestrial landscapes and the sights they might someday reveal to human explorers.

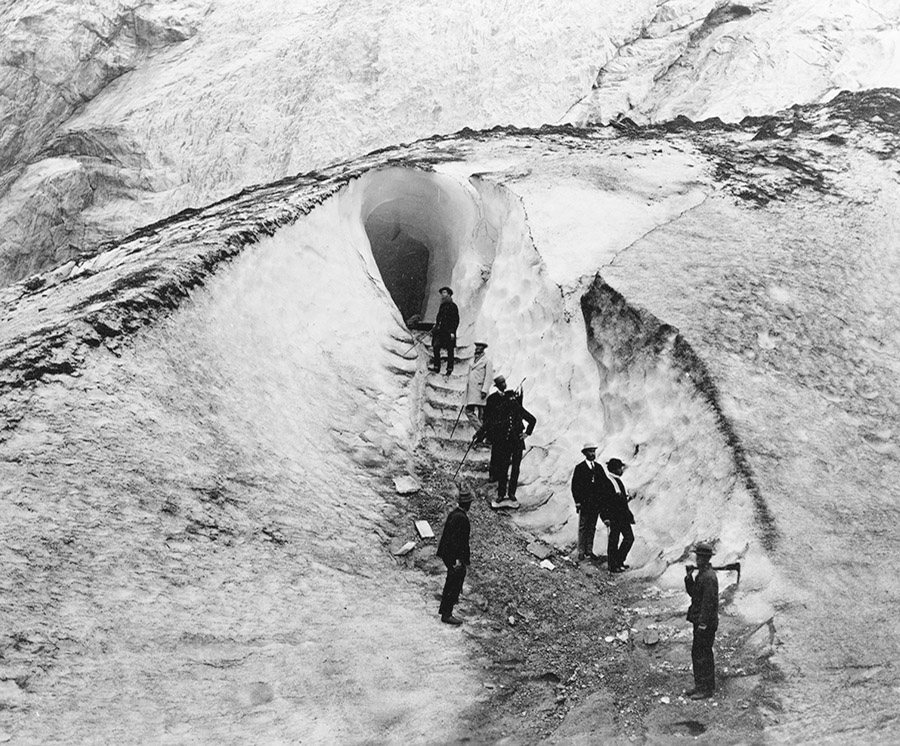

[Image: Walking into a glacier: “Grindelwald Grotto, Bernese Oberland, Switzerland,” courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division].

[Image: Walking into a glacier: “Grindelwald Grotto, Bernese Oberland, Switzerland,” courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division].

Art historians would gaze in awe at offworld glaciers of carbon dioxide ice and howling massifs of frozen nitrogen, where volcanoes erupt not with liquid rock but with “ice slurries” and groundwater exploding onto the landscape with the force of a Kilauea.

Perhaps someday you’ll be able to get a degree in the field of exploratory xenoglaciology, the study of rare and incredible landforms made of frozen chemicals in space.

(“Wild Ice” story spotted via @nicolatwilley).

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

[Images: Courtesy of the

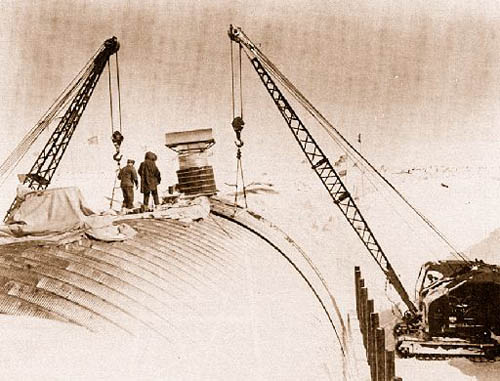

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via

[Image: Camp Century under construction; photograph via

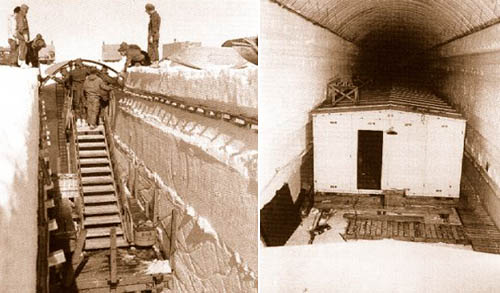

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

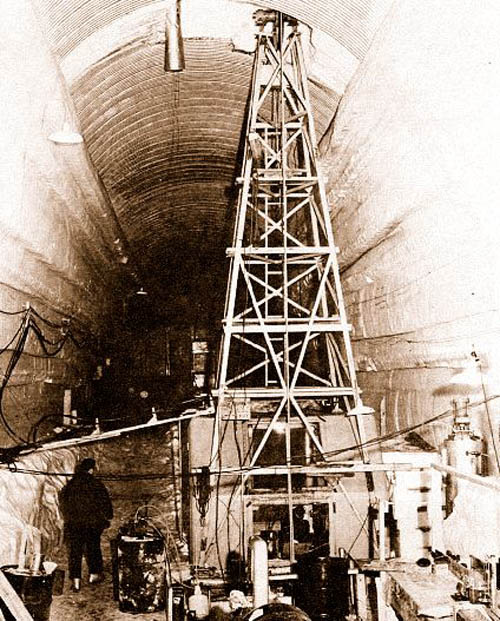

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via

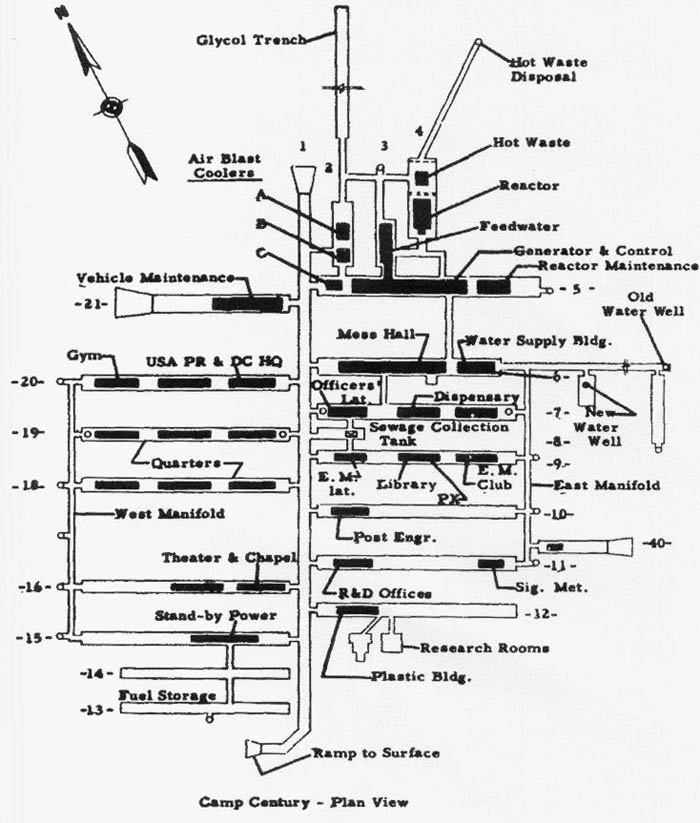

[Images: Camp Century under construction; photographs via  [Image: The plan of Camp Century; via

[Image: The plan of Camp Century; via  [Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the

[Image: U.S. Army photograph, via the

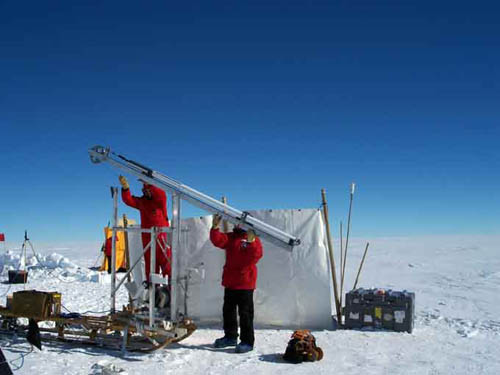

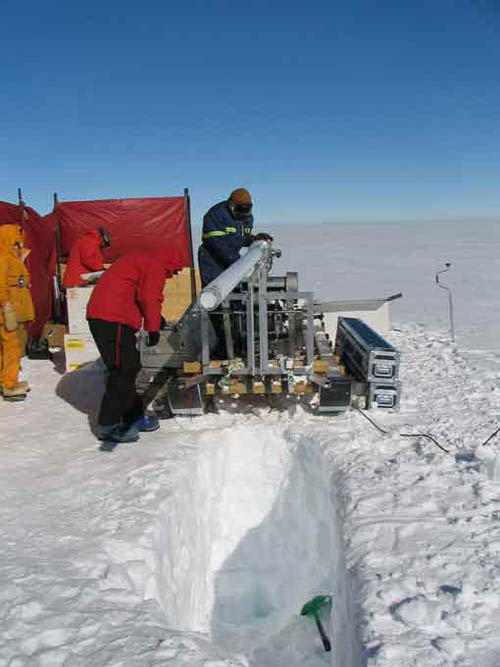

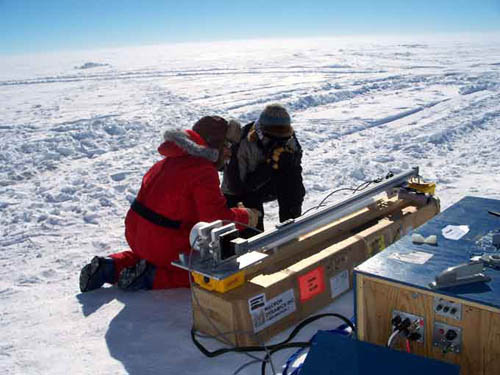

[Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007  [Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007

[Images: From the 2006-2007

[Images: From the 2006-2007  [Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007  [Image: “Beardmore Glacier, slicing its way through the Transantarctic Mountains.” Via

[Image: “Beardmore Glacier, slicing its way through the Transantarctic Mountains.” Via  [Image: The aurora borealis – yes, the Northern, not Southern, Lights. Sorry. Via

[Image: The aurora borealis – yes, the Northern, not Southern, Lights. Sorry. Via  [Image: The BLDGBLOG glacial cathedral, adapted from

[Image: The BLDGBLOG glacial cathedral, adapted from  [Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From

[Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From  [Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From

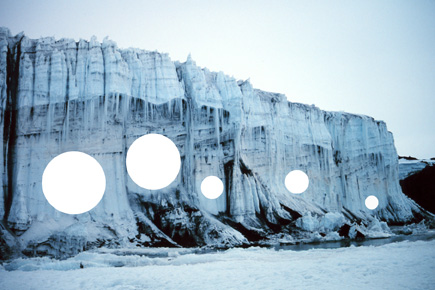

[Image: Jackie Dee Grom, Antarctic ventifacts. From  [Image: From a truly spectacular collection of Antarctic images at

[Image: From a truly spectacular collection of Antarctic images at  [Image: Again, from the fantastic collection of Antarctic images at

[Image: Again, from the fantastic collection of Antarctic images at