[Image: Binnewater Kilns, photo by BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: Binnewater Kilns, photo by BLDGBLOG.]

While I was over in New York State last fall, reporting both the “witch houses” piece for The New Yorker and the Middletown High School piece for The Guardian, I stopped off in the town of Rosendale, enticed there by several things I noticed on Google Maps.

[Image: The Rosendale Trestle, photo by BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: The Rosendale Trestle, photo by BLDGBLOG.]

First was what turned out to be a satirical reference to something called the Geo Refrigeration Crevice, which, even on its own, sounded worth a side-trip. But, in the exact same area, there were also photos of an incredible-looking railway bridge converted to a hiking path that I wanted to walk across; there were these gorgeous, ruined kilns built into the hillside; and there were supposedly huge caves.

How on Earth could I drive past all that without stopping?

[Image: Caves everywhere! Photos by BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: Caves everywhere! Photos by BLDGBLOG.]

Being—perhaps to my Instagram followers’ frustration—an avid hiker, I spent far more time there than I should have, mostly looking down into jagged crevasses that extended past the roots of trees, carpeted in fallen leaves, often hidden beneath great, shipwrecked jumbles of boulders slick with the waters of temporary streams.

I crossed the bridge and was ready to hit the road again, when I saw another site of interest on the map. I decided to walk all the way down and around to something called the Widow Jane Mine.

Having visited many mines in my life, I was expecting something like a small arched hole in the side of a hill, probably guarded with a locked gate. Instead, hiking into the woods past some sort of private home/closed mining museum, the ground still damp from rain, I found myself stunned by the unexpected appearance of these huge, moaning, jaw-like holes blasted into the Earth.

[Image: An entrance to the Widow Jane Mine; photo by BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: An entrance to the Widow Jane Mine; photo by BLDGBLOG.]

I walked inside and immediately saw the space was huge: a massive artificial cavern extending far back into the hillside. Excuse my terribly lit iPhone photos here, but these images should give you at least a cursory sense of the mine’s scale.

[Image: Inside the Widow Jane Mine; photos by BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: Inside the Widow Jane Mine; photos by BLDGBLOG.]

Several things gradually became clear as my eyes adjusted to the darkness.

One, I was totally alone in there and had no artificial illumination beyond my phone, whose light was useless. Two, a great deal of the mine was flooded, meaning that the true extent of its subterranean workings was impossible to gauge; I began fantasizing about returning someday with a canoe and seeing how far back it all really goes.

[Image: Flooding inside the Widow Jane Mine; photo by BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: Flooding inside the Widow Jane Mine; photo by BLDGBLOG.]

Three, there were plastic lawn chairs everywhere. And they were facing the water.

While the actual explanation for this would later turn out to be both entirely sensible and somewhat anticlimactic—the mine, it turns out, is occasionally used as a performance venue for unusual concerts and events—it was impossible not to fall into a more Lovecraftian fantasy, of people coming here to sit together in the darkness, waiting patiently for something to emerge from the smooth black waters of a flooded mine, perhaps something they themselves have invited to the surface…

[Image: Lawn chairs facing the black waters of a flooded mine; photo by BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: Lawn chairs facing the black waters of a flooded mine; photo by BLDGBLOG.]

In any case, at that point I couldn’t be stopped. While trying to figure out where in the world I had left my rental car, I noticed something else in Google’s satellite view of the area—some sort of abandoned factory complex in the woods—so I headed out to find it.

On the way there, still totally alone and not hiking past a single other person, there was some sort of Blair Witch house set back in the trees, collapsing under vegetation and water damage, with black yawning windows and graffiti everywhere. I believe it is this structure in the satellite pic.

[Image: A creepy, ruined house in the woods, photo by BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: A creepy, ruined house in the woods, photo by BLDGBLOG.]

Onward I continued, walking till I made it, finally, to this sprawling cement plant facility of some sort just standing there in a clearing.

[Image: Cement world; photos by BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: Cement world; photos by BLDGBLOG.]

I wandered into the silos, looking at other people’s graffiti…

[Image: “Born to Die”—it’s hard to argue with that, although when I texted this photo to a friend he thought it said “Born to Pie,” which I suppose is even better. Photo by BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: “Born to Die”—it’s hard to argue with that, although when I texted this photo to a friend he thought it said “Born to Pie,” which I suppose is even better. Photo by BLDGBLOG.]

…before continuing on again to find my car.

Then, though, one more crazy thing popped up, sort of hidden behind those kilns in the opening photo of this post.

There was a door in the middle of the forest! With a surveillance camera!

[Image: Photos by BLDGBLOG.]

[Image: Photos by BLDGBLOG.]

It turns out this door leads down into the massive document-storage caverns of Iron Mountain located nearby, a company whose subterranean archive fever was documented in The New Yorker several years ago (albeit referring to a slightly different location of the firm). I would guess that this is the approximate location of that door.

This was confirmed for me by a man sitting alone in a public works truck back at the Binnewater Kilns parking lot, near my rental car. He was smoking a cigar and listening to the radio with his window rolled down when I walked up to the side of his truck and said, “Hey, man, what’s that door in the woods?”

[Image: As if a lighter-than-air geometric fluid became temporarily frozen between two gateways of masonry, it’s just a bridge over the Norderelbe in Hamburg, Germany; photograph by Georg Koppmann (1888) from the collection of the

[Image: As if a lighter-than-air geometric fluid became temporarily frozen between two gateways of masonry, it’s just a bridge over the Norderelbe in Hamburg, Germany; photograph by Georg Koppmann (1888) from the collection of the  [Image: Saltair, photographed ca. 1901, courtesy of the

[Image: Saltair, photographed ca. 1901, courtesy of the  [Image: Via

[Image: Via

[Image: An otherwise unrelated shot of rebar used in road construction; via

[Image: An otherwise unrelated shot of rebar used in road construction; via

[Image: Photo by

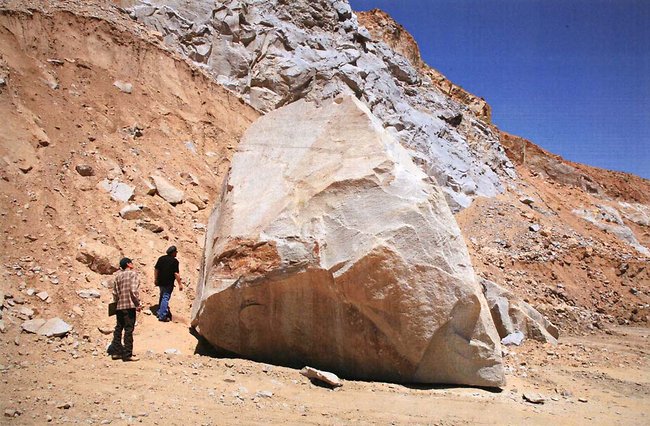

[Image: Photo by  [Image: The rock in question; photo by Monica Almeida, courtesy of the

[Image: The rock in question; photo by Monica Almeida, courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by Monica Almeida, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Monica Almeida, courtesy of the