The so-called “Yolo Buggy” was not a 19th-century adventure tourism vehicle for those of us who only live once; it was a mobile building, field shelter, and geopolitical laboratory for measuring the borders of an American county. Yolo County, California.

The so-called “Yolo Buggy” was not a 19th-century adventure tourism vehicle for those of us who only live once; it was a mobile building, field shelter, and geopolitical laboratory for measuring the borders of an American county. Yolo County, California.

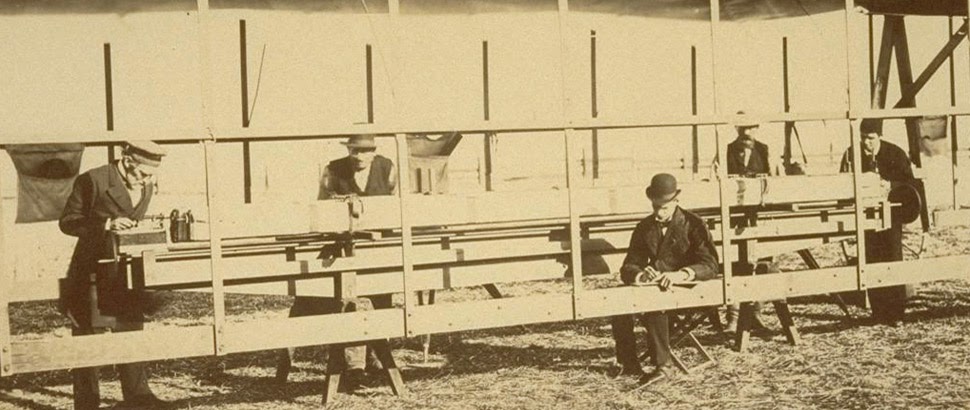

The “moveable tent or ‘Yolo Buggy,'” as the libraries at UC Berkeley describe it, helped teams of state surveyors perform acts of measurement across the landscape in order to mathematically understand—and, thus, to tax, police, and regulate—the western terrain of the United States. It was a kind of Borgesian parade, a carnival of instruments on the move.

The “moveable tent or ‘Yolo Buggy,'” as the libraries at UC Berkeley describe it, helped teams of state surveyors perform acts of measurement across the landscape in order to mathematically understand—and, thus, to tax, police, and regulate—the western terrain of the United States. It was a kind of Borgesian parade, a carnival of instruments on the move.

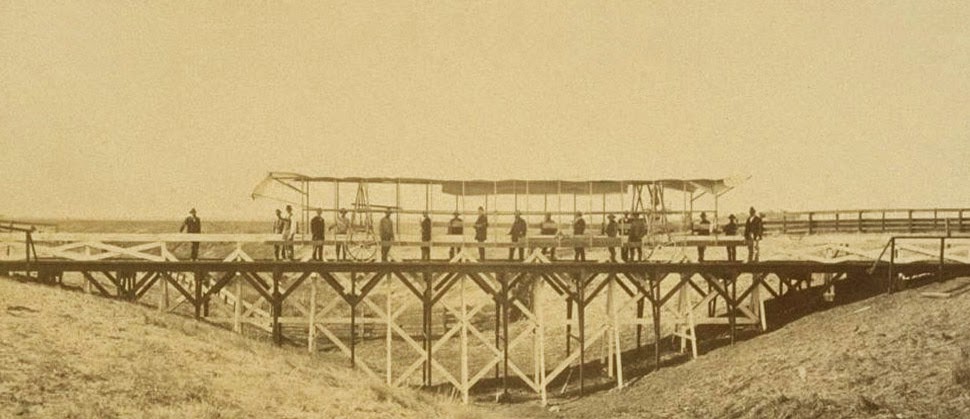

The resulting “Yolo Baseline” and the geometries that emerged from it allowed these teams to establish a constant point of cartographic reference for future mapping expeditions and charts. In effect, it was an invisible line across the landscape that they tried to make governmentally real by leaving small markers in their wake. (Read more about meridians and baselines over at the Center for Land Use Interpretation).

The resulting “Yolo Baseline” and the geometries that emerged from it allowed these teams to establish a constant point of cartographic reference for future mapping expeditions and charts. In effect, it was an invisible line across the landscape that they tried to make governmentally real by leaving small markers in their wake. (Read more about meridians and baselines over at the Center for Land Use Interpretation).

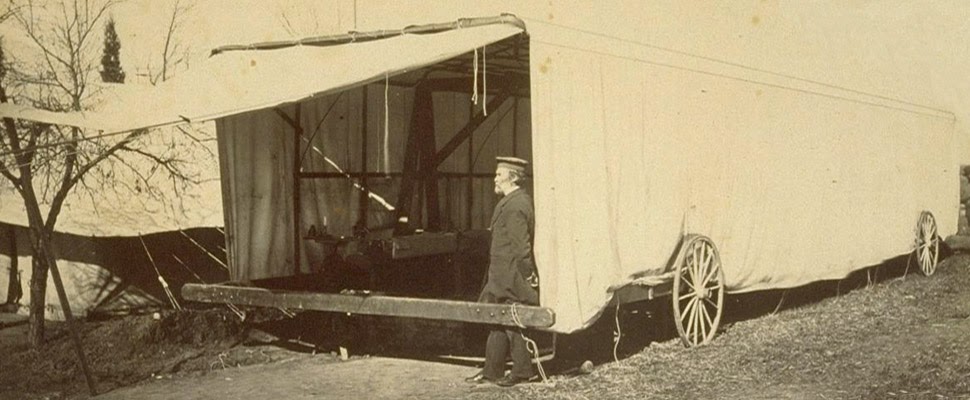

In the process, these teams carried architecture along with them in the form of the “moveable tent” seen here—which was simultaneously a room in which they could stay out of the sun and a pop-up work station for making sense of the earth’s surface—and the related tower visible in the opening image.

In the process, these teams carried architecture along with them in the form of the “moveable tent” seen here—which was simultaneously a room in which they could stay out of the sun and a pop-up work station for making sense of the earth’s surface—and the related tower visible in the opening image.

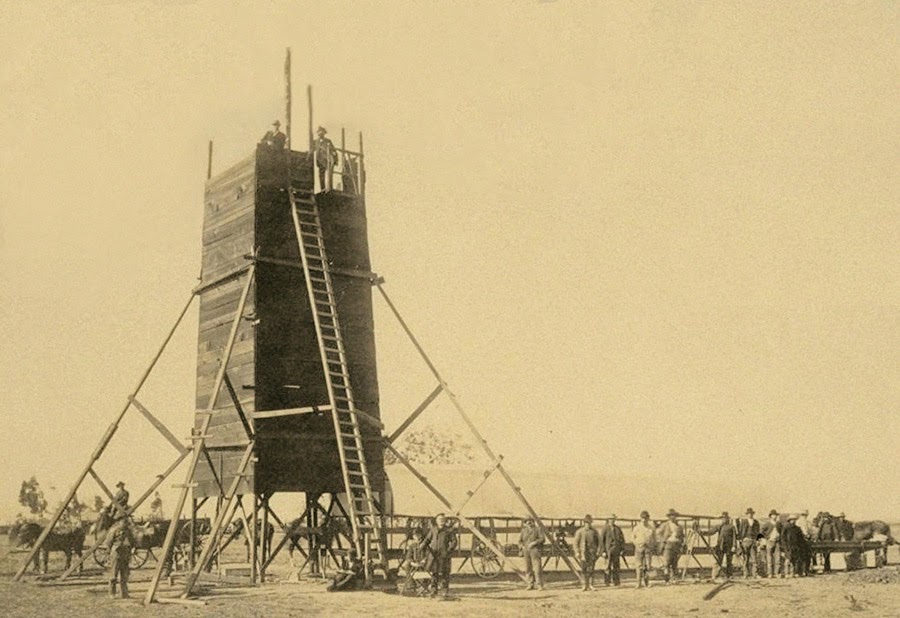

That control tower allowed the teams’ literal supervisors to look back at where they’d come from and to scan much further ahead, at whatever future calculations of the grid they might be able to map in the days to come. You could say that it was mobile optical infrastructure for gaining administrative control of new land.

That control tower allowed the teams’ literal supervisors to look back at where they’d come from and to scan much further ahead, at whatever future calculations of the grid they might be able to map in the days to come. You could say that it was mobile optical infrastructure for gaining administrative control of new land.

Like a dust-covered Tron of the desert, surrounded by the invisible mathematics of a grid that had yet to be realized, these over-dressed gentlemen of another century helped give rise to an abstract model of the state. Their comparatively minor work thus contributed to a virtual database of points and coordinates, something immaterial and totally out of scale with the bruised shins and splintered fingers associated with moving this wooden behemoth across the California hills.

Like a dust-covered Tron of the desert, surrounded by the invisible mathematics of a grid that had yet to be realized, these over-dressed gentlemen of another century helped give rise to an abstract model of the state. Their comparatively minor work thus contributed to a virtual database of points and coordinates, something immaterial and totally out of scale with the bruised shins and splintered fingers associated with moving this wooden behemoth across the California hills.

(All images courtesy UC Berkeley/Calisphere).

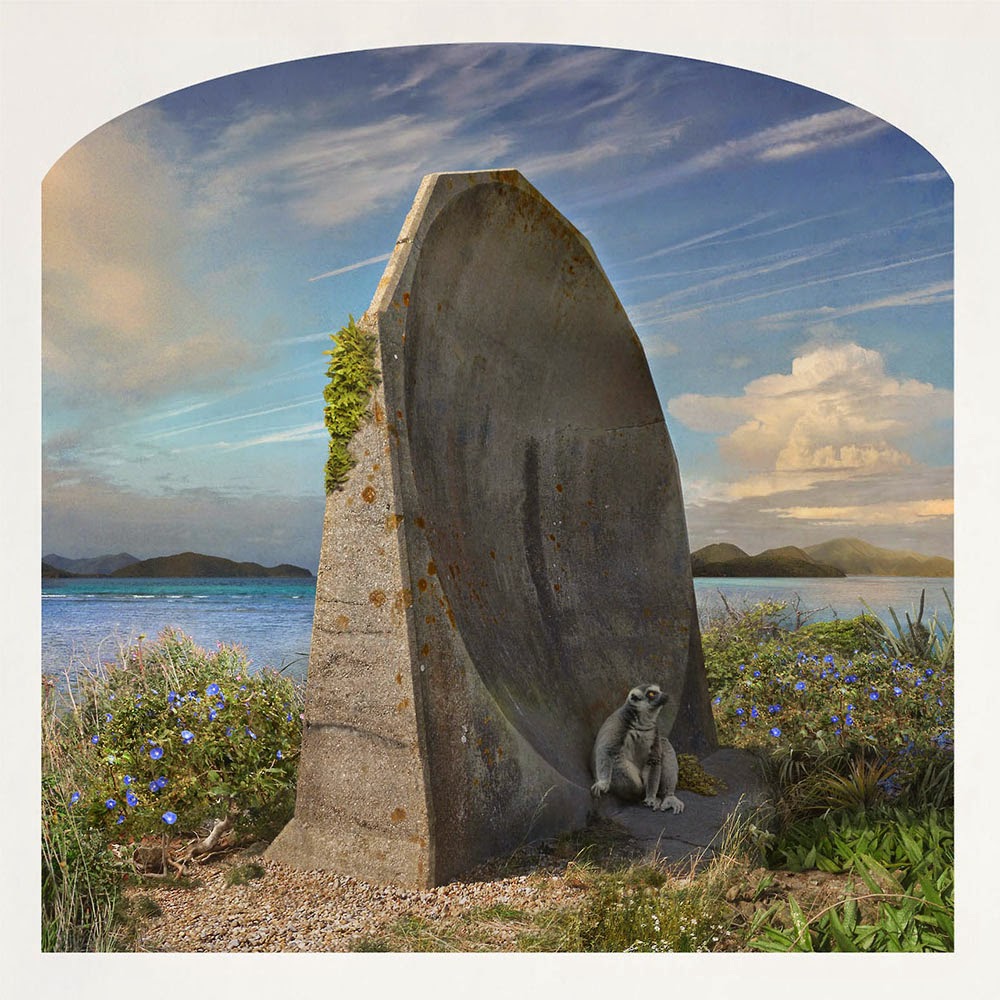

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Images: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Images: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy  [Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

[Image: Kahn & Selesnick, courtesy

If you’re in the Bay Area at the end of month, consider attending an event called

If you’re in the Bay Area at the end of month, consider attending an event called  [Image: The

[Image: The