New archaeological discoveries continue to be made as glacial ice patches melt, revealing their previously unknown contents. Teams of archaeologists and historians have taken to wandering around newly exposed ground in locations as diverse as Norway, the Alps, and Glacier National Park.

Animal bones and cultural artifacts, including 3,000-year old woven bark baskets and old wooden tools, are most prevalent.

[Image: Courtesy Oppland County Council. Photo by Johan Wildhagen/Palookaville, via Archaeology].

[Image: Courtesy Oppland County Council. Photo by Johan Wildhagen/Palookaville, via Archaeology].

“Prehistoric ice is melting and revealing artifacts and organic materials like wood, feather, and bone that have been frozen within the snow for thousands of years,” Kevin Grange writes in National Parks magazine. “As temperatures continue to rise, researchers and Native people are racing to find these materials before they vanish.”

“Enter the ice patch archaeologist,” Grange continues. “These explorers don’t sift through the dirt for artifacts—they prowl the retreating edges of ice patches and glaciers, searching for ancient tools, weapons, wood fragments, bones, and even animal dung. Glaciers move, sort, and grind material down, but ice patches—the result of windblown snow accumulating on alpine slopes—are unique for their ability to stay put and preserve anything frozen within them.”

But there is a justified sense of urgency, as many of the organic materials begin to decay as soon as they’re exposed; if they aren’t found soon after being revealed, they might not be found at all.

The loss of cultural heritage as ice patches give up their archaeological goods was the subject of a 2011 letter to the editors of Nature Geoscience by Kathryn Molyneaux and Dave S. Reay. “In the central Asian Altai Mountains,” Molyneaux and Reay write, “approximately 700 tombs have been preserved for 2,500 years by ice lenses or permafrost. They contain frozen mummies, wood, leather and textiles, which are very rarely preserved and can provide a unique insight into the culture of prehistoric societies in this region. As a result of increasing ground and surface temperatures over the past century, these tombs and their deposits are now within only a few degrees of melting.”

Although I suppose this sounds like the set-up for a new supernatural thriller—in which ancient kings arise from the ice of Central Asia, stepping forth from their melting tombs—in reality, it often has tense emotional and political consequences.

[Image: A shot of the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site by Gleb Raygorodetsky, courtesy of Our World 2.0].

[Image: A shot of the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site by Gleb Raygorodetsky, courtesy of Our World 2.0].

Here, the authors refer to the rise of “rescue archaeology,” where artifacts are rapidly and even haphazardly removed from an endangered site, in operations “carried out under less than ideal conditions with limited funding and a lack of long-term goals. For example,” they add, “a coastal cemetery near Barrow, Alaska is eroding at rates of up to 20 [meters per year], because the sea ice that used to protect the coastline has receded. As a result, indigenous people’s remains that date back to the fourth century AD are being exposed at a rapid rate. At present, rescue work is carried out annually in an attempt to document, stabilize and relocate the cemetery material that is being washed away owing to high beach erosion.”

In the Altai region itself, meanwhile, the exhumation of a “princess” led to “political unrest in the local shaman community,” Molyneaux and Reay write. These disturbed and literally geopolitical circumstances are only set to grow.

[Image: Two shots from the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site by Gleb Raygorodetsky, courtesy of Our World 2.0].

[Image: Two shots from the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site by Gleb Raygorodetsky, courtesy of Our World 2.0].

Writing for the somewhat unfortunately named publication Our World 2.0, Gleb Raygorodetsky reiterates the point that the changing ground conditions of the region that once so effectively “preserved the remains of the Altai’s ancestors in burial kurgans [or tombs] for thousands of years is disappearing, melting away because of steadily rising air and ground temperatures in the region. Climate change is literally melting away the cultural heritage of the Altai people, a rich and irreplaceable part of the global heritage.”

It’s worth noting that there have been some architectural proposals for helping with the in-situ preservation of these frozen tombs. As Raygorodetsky writes, “UNESCO and Ghent University, along with their Russian partners, have been cataloguing the Altai’s frozen tombs to help develop conservation and preservation plans. Some of the proposed solutions include elaborate schemes to shade each individual tomb from direct sunlight to stabilize its temperature.”

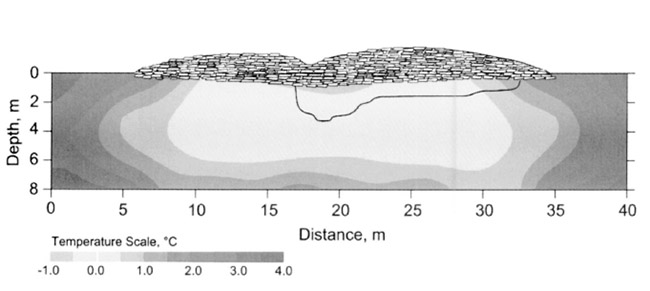

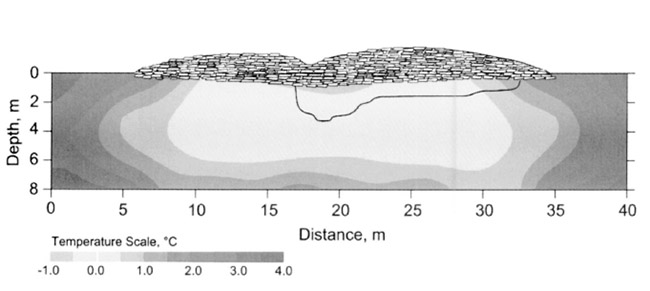

[Image: Diagram of the thermal effects of an Altai rock tomb or kurgan, from “Saving the Frozen Scythian Tombs of the Altai Mountains” by Jean Bourgeois, Alain De Wulf, Rudi Goossens and Wouter Gheyle].

[Image: Diagram of the thermal effects of an Altai rock tomb or kurgan, from “Saving the Frozen Scythian Tombs of the Altai Mountains” by Jean Bourgeois, Alain De Wulf, Rudi Goossens and Wouter Gheyle].

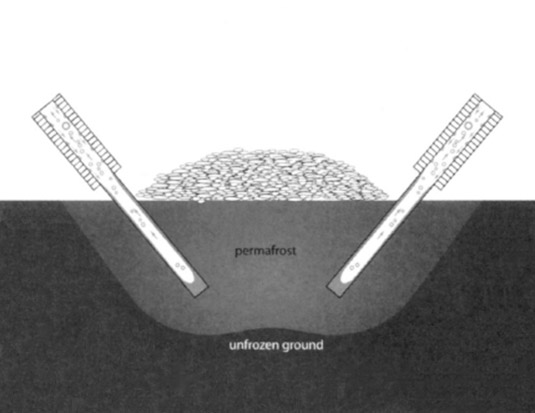

Here, Raygorodetsky refers to a 2007 paper originally published in World Archaeology, called “Saving the Frozen Scythian Tombs of the Altai Mountains,” where the possibility of constructing thermal shading devices to protect the tombs from melting is explored.

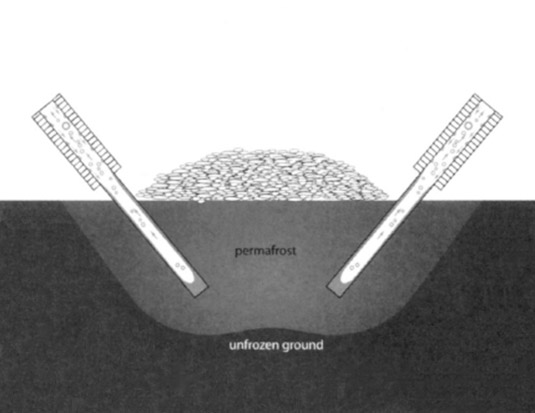

However, considering the visually intrusive nature of such shelters, not to mention the expense of construction and upkeep, the authors instead suggest what amounts to refrigerating the ground: proposing a solution that would involve “self-regulating seasonally acting cooling devices or thermosyphons. They act like refrigerators but without needing an external power source. By extracting heat from the ground and dissipating it into the air, they lower the ground temperature and prevent the degradation of permafrost.”

As such, these would be not unlike the ground-refrigeration columns currently used to artificially englaciate the ground beneath the epic Beijing-Lhasa high-altitude, pressurized train in China & Tibet, or artificial glaciation as a form of architectural design.

[Image: Diagram of archaeological ground-refrigeration techniques, from “Saving the Frozen Scythian Tombs of the Altai Mountains” by Jean Bourgeois, Alain De Wulf, Rudi Goossens and Wouter Gheyle].

[Image: Diagram of archaeological ground-refrigeration techniques, from “Saving the Frozen Scythian Tombs of the Altai Mountains” by Jean Bourgeois, Alain De Wulf, Rudi Goossens and Wouter Gheyle].

But perhaps precise cataloging of the exposed artifacts really is all that can be done in most locations.

In the most recent issue of Archaeology, journalist Andrew Curry tags along with a team of surveyors and archaeologists as they explore the Jotunheim Mountains of Norway.

As the ice fields recede due to changing temperatures, ancient artifacts, such as 3,400-year old leather shoes, are being uncovered more and more frequently, now found just sitting there on the rocks. Finding these and other soon-to-be-disturbed objects is, Curry writes, “an effort that combines high-tech mapping, glaciology, climate science, and history. When conditions are right, it’s as simple as picking the past up off the ground.”

[Image: Courtesy Espen Finstad/Oppland County Council. Photos by Johan Wildhagen/Palookaville and Andrew Curry, via Archaeology].

[Image: Courtesy Espen Finstad/Oppland County Council. Photos by Johan Wildhagen/Palookaville and Andrew Curry, via Archaeology].

Growing beards and loaded down with survey gear, the archaeologists Curry traveled with hiked up into the mountains, following meltwater streams to the ice patches they came from. At one of their camps, sleeping inside “Everest-rated” tents, one of the scientists tells Curry of an experience from a prior year’s survey work.

They had been ready to return home, the archaeologist explains, hiking carefully through a heavy fog, when they noticed a woven tunic and scattered leather goods lying on the rocks down at their feet.

Then the fog lifted and they saw the landscape around them, “littered with leather, textiles, wood, and animal dung”—artifacts everywhere—an archaeological site newly exposed from its frozen burial like a fully-stocked stage set dramatically revealed, dream-like, on all sides, an ancient open-air exhibition that had only recently been hidden from view.

(For more things locked in ice, suddenly revealed, see Ice Patch Archaeology earlier on BLDGBLOG).

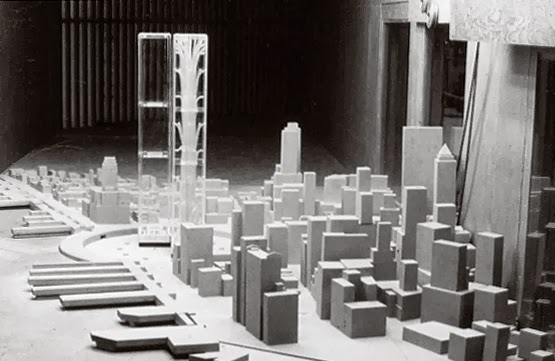

[Image: A “wind tunnel model of the New York Trade Center (study by Drs. J.E.Cermak and A.G. Davenport in the Colorado State University boundary layer wind tunnel for L.E. Robertson of Worthington, Skilling, Helle and Jackson (1964),” via Studio-X NYC].

[Image: A “wind tunnel model of the New York Trade Center (study by Drs. J.E.Cermak and A.G. Davenport in the Colorado State University boundary layer wind tunnel for L.E. Robertson of Worthington, Skilling, Helle and Jackson (1964),” via Studio-X NYC].

[Image: David Kilcullen, from

[Image: David Kilcullen, from  [Image: David Kilcullen, from

[Image: David Kilcullen, from  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Walking into a glacier: “

[Image: Walking into a glacier: “

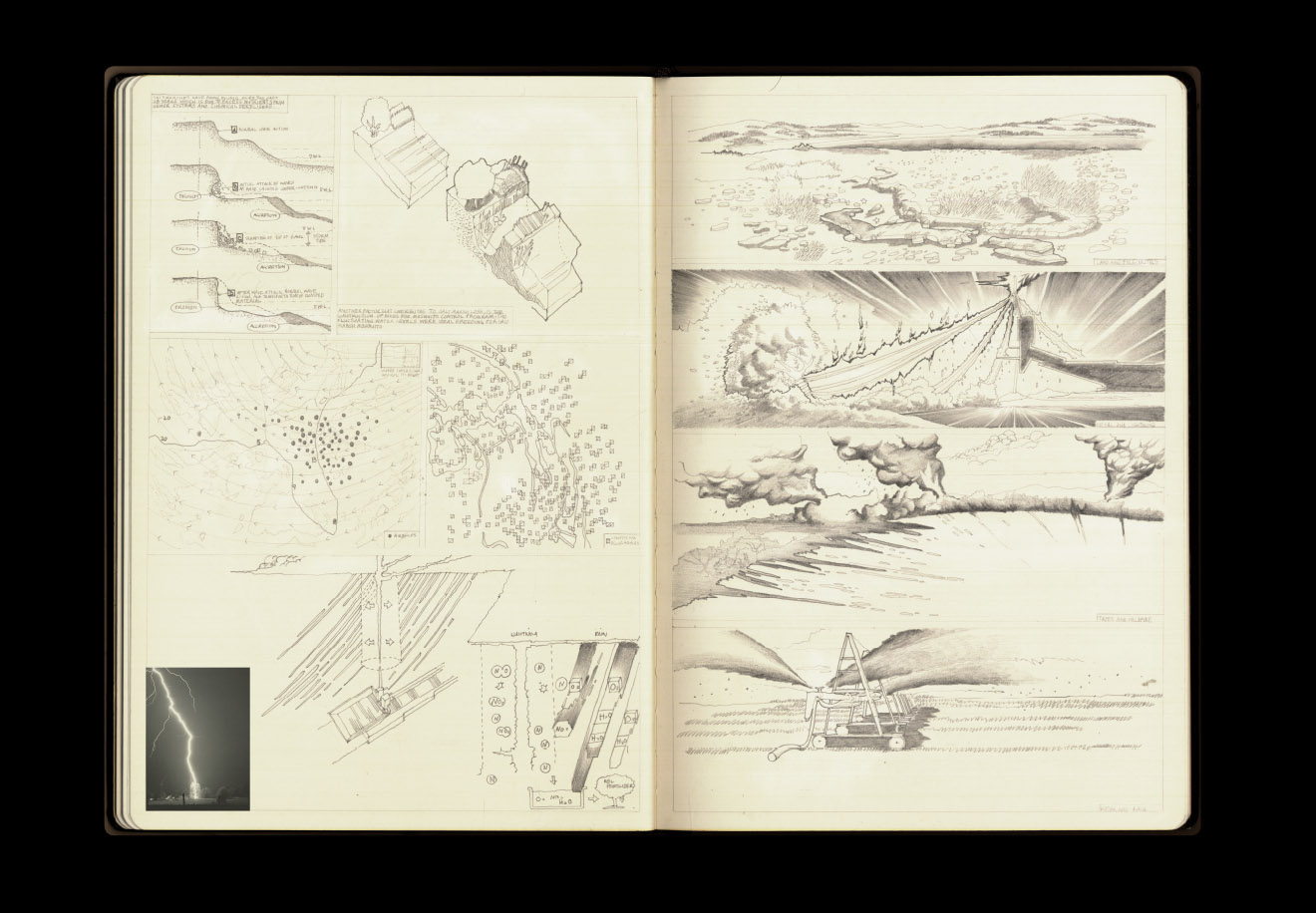

[Image: From the paper “

[Image: From the paper “ [Image: From the paper “

[Image: From the paper “ [Image: From the paper “

[Image: From the paper “ [Image: From the paper “

[Image: From the paper “ [Image: The stricken poplar tree, from “

[Image: The stricken poplar tree, from “

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida’s

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida’s

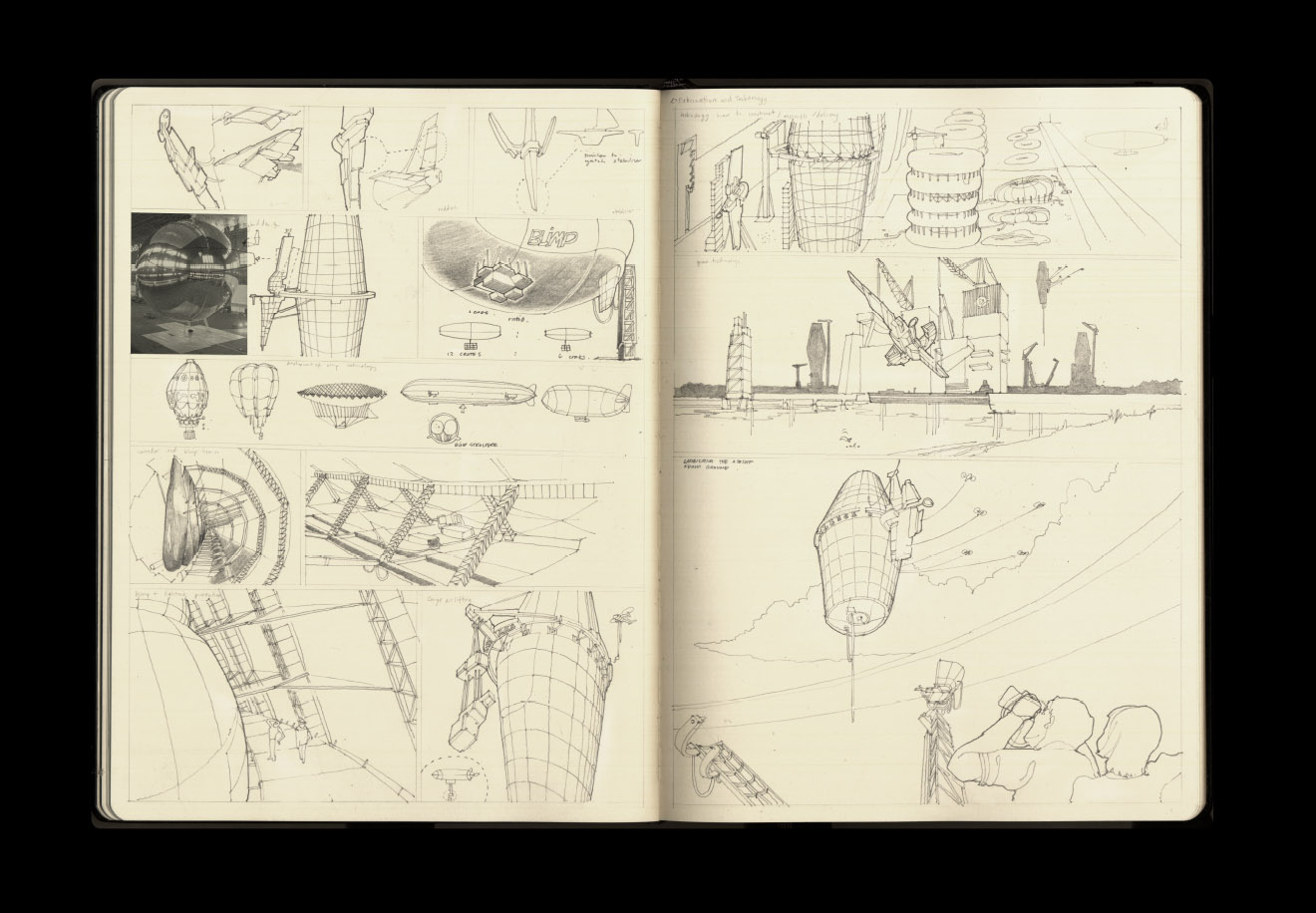

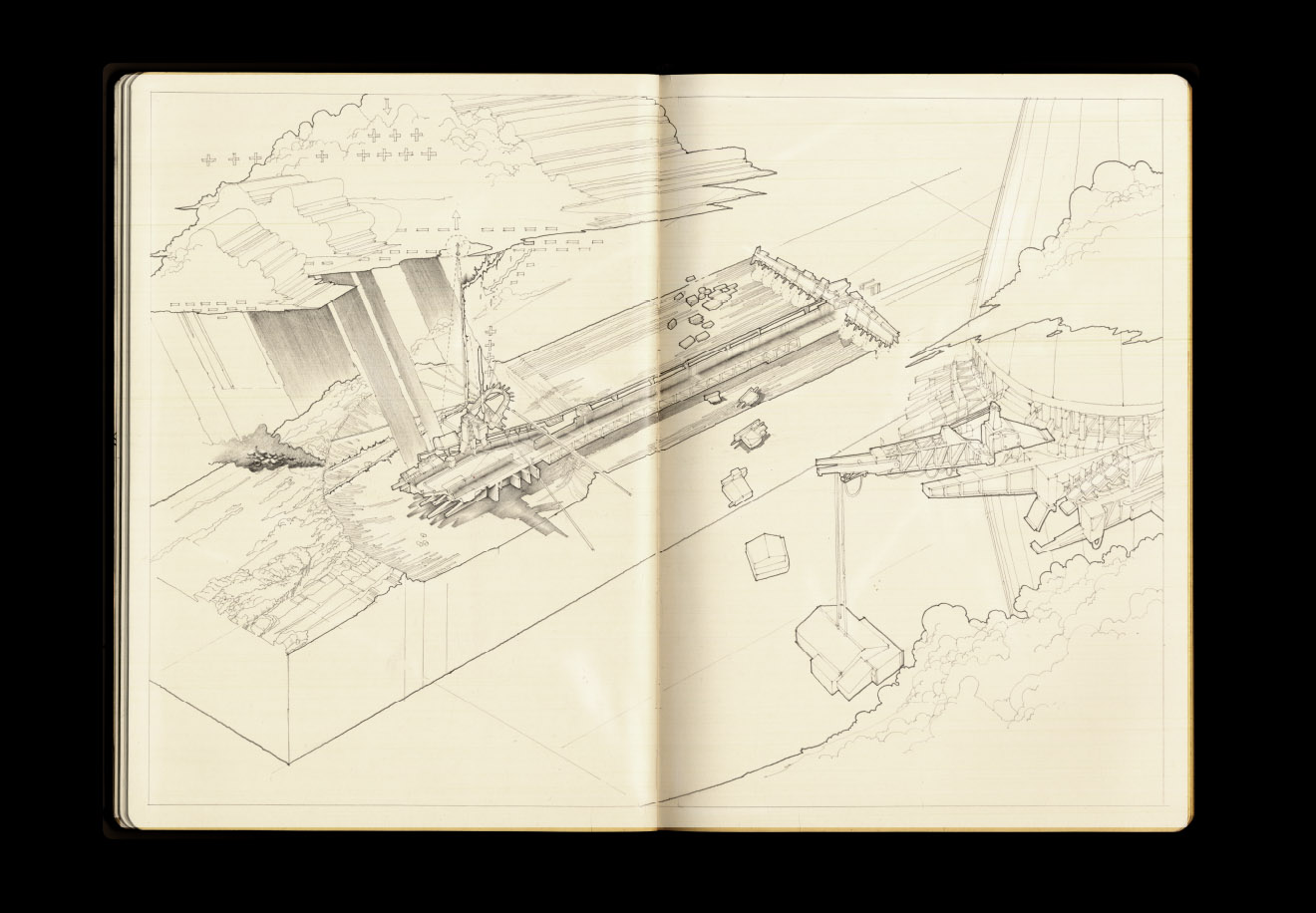

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the  [Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the  [Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida’s

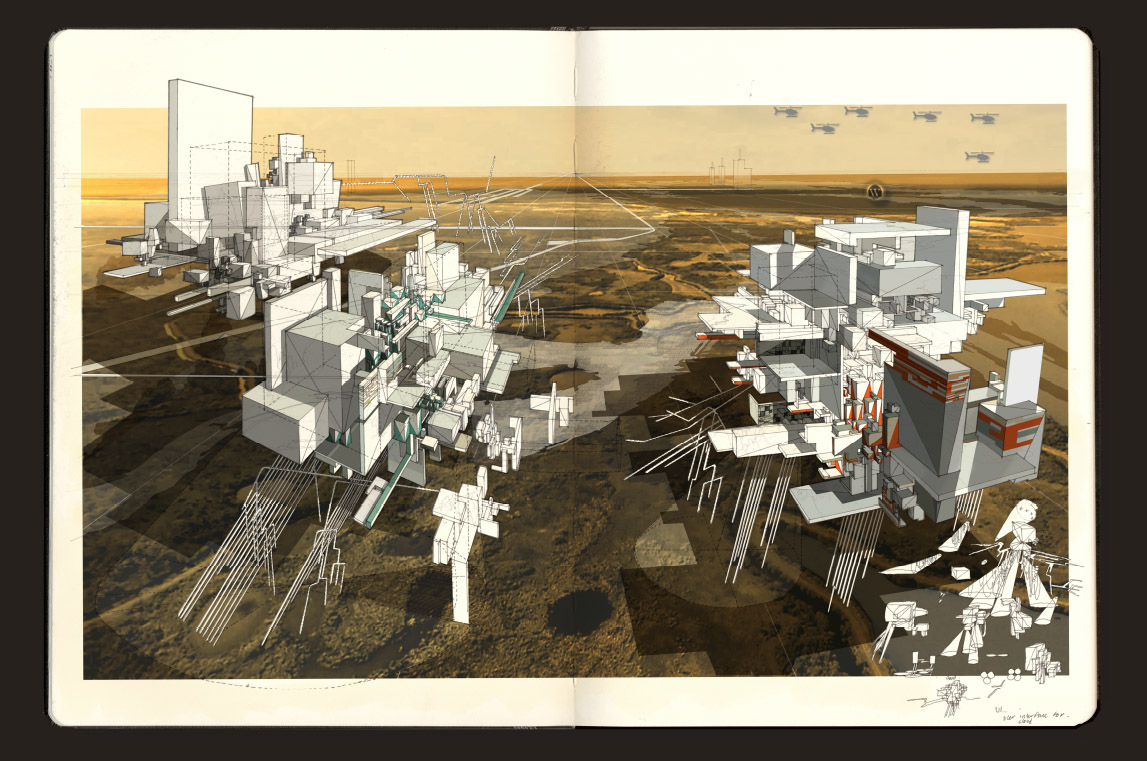

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida’s  [Image: Aerial collage view of the lightning farm, by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the

[Image: Aerial collage view of the lightning farm, by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the  [Image: Collage of the lightning farm, by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the

[Image: Collage of the lightning farm, by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the  [Image: Farah Aliza Badaruddin].

[Image: Farah Aliza Badaruddin].

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the

[Image: Courtesy Oppland County Council. Photo by

[Image: Courtesy Oppland County Council. Photo by  [Image: A shot of the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site by Gleb Raygorodetsky, courtesy of

[Image: A shot of the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site by Gleb Raygorodetsky, courtesy of

[Image: Two shots from the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site by Gleb Raygorodetsky, courtesy of

[Image: Two shots from the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site by Gleb Raygorodetsky, courtesy of  [Image: Diagram of the thermal effects of an Altai rock tomb or kurgan, from “

[Image: Diagram of the thermal effects of an Altai rock tomb or kurgan, from “ [Image: Diagram of archaeological ground-refrigeration techniques, from “

[Image: Diagram of archaeological ground-refrigeration techniques, from “ [Image: Courtesy Espen Finstad/Oppland County Council. Photos by

[Image: Courtesy Espen Finstad/Oppland County Council. Photos by

[Image: A SWORDS unit firing; photo via

[Image: A SWORDS unit firing; photo via  [Image: Knights at the

[Image: Knights at the

[Image: Ancient Egyptian jewelry made from meteorites; photo courtesy of

[Image: Ancient Egyptian jewelry made from meteorites; photo courtesy of  [Image: Space buddha! Photo by Dr. Elmar Buchner, via

[Image: Space buddha! Photo by Dr. Elmar Buchner, via

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: Another view of “

[Image: Another view of “

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “