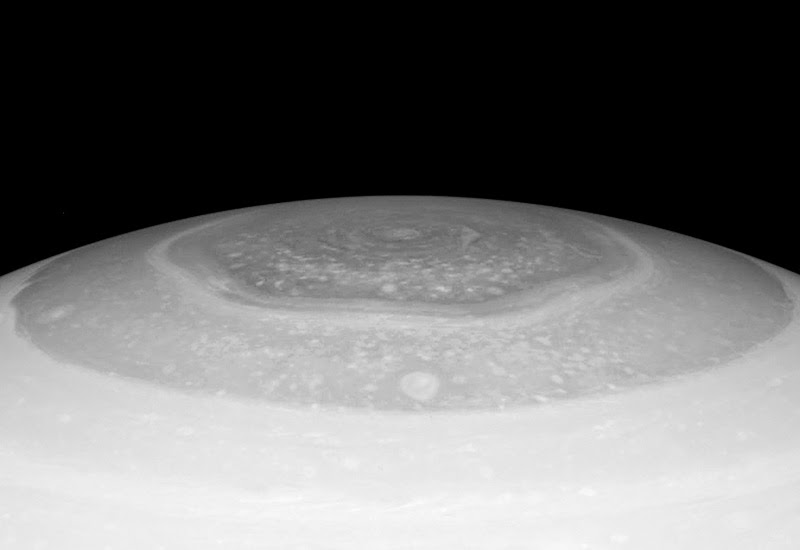

[Image: A “hurricane” at Saturn’s south pole, via NASA; see also The Planetary Weather Report].

[Image: A “hurricane” at Saturn’s south pole, via NASA; see also The Planetary Weather Report].

In Frédéric J. Pont’s new book Alien Skies, he describes the atmospheres of other planets: what storms are like, what the clouds are made of, how a sunset might appear through a chemical haze at high pressure on another world.

He points out, for example, that many of these “alien skies” would likely consist of wildly unfamiliar shapes and formations, as different elements would be capable of condensing to form clouds at ever-increasing heights.

As he puts it, “The type of compound likely to condense into clouds depends on the temperature, and varies from planet to planet. Earth has water clouds. Carbon dioxide clouds sometimes grace the Martian sky, and Venus is shrouded in sulphuric acid clouds. On the giant planets, successive cloud decks are made of different compounds as the temperature increases in the deeper layers.”

[Image: J.M.W. Turner, “Storm at Sea” (1824), courtesy of Tate Britain].

[Image: J.M.W. Turner, “Storm at Sea” (1824), courtesy of Tate Britain].

However, I should emphasize that all of this stuff needs to be put into the context of the Hudson River School and European Romanticism, of so-called “representational exploration art” of earlier scientific expeditions, where humans attempted to visually depict the wild worlds they’d plunged themselves into.

You shouldn’t see this stuff and think of astronomy, in other words. You should think of J.M.W. Turner or John Constable, of huge coastal storms and mountain passes lit by lightning, of ships dashed on the rocks as wrathful pillars of dark cloud spiral into the blackness of space above terrified figures for whom weather bears traces of omnipotence.

Only now the weather is even more spectacular, and it is glimpsed on planets more exotic than any continent to which artists have traveled before.

The weather on other planets should not be left only to scientists, in other words, but needs always to be considered in the context of art and landscape history.

[Image: John Constable, “Seascape Study with Rain Cloud” (c. 1824), via Wikipedia].

[Image: John Constable, “Seascape Study with Rain Cloud” (c. 1824), via Wikipedia].

In any case, Pont explains that, as you move higher into some of the otherworldly atmospheres he describes, you would continually pass into entirely new elements—carbon dioxide, methane, ammonia—now frozen or condensed, billowing and moving about in the wind, capable of assuming structures unlike anything seen on Earth, vast “waves, spirals and tentacles,” or “unpredictable storm patterns” and even giant hexagons, as weird configurations unlock through a chemical sky.

[Image: The great hexagon at Saturn’s north pole, via Universe Today].

[Image: The great hexagon at Saturn’s north pole, via Universe Today].

The book is less landscape poetry, however—sadly, after all, as what an incredible book of poems it would be, simply describing the skies of other worlds—than a scientific introduction to atmospheric chemistry, including here on Earth. But don’t hold that against it.

For instance, during Pont’s survey of the atmosphere of the early Earth, he makes an interesting and particularly evocative observation, one worth repeating here.

As he points out, the early Earth—for a period that lasted nearly a billion years—was quite boring, geologically speaking, “because nothing much happened to the rocks in a billion years.” But the skies were another matter.

[Image: A false-color image of the “hurricane” at Saturn’s south pole, via NASA; the eye is estimated to be 1,250 miles wide].

[Image: A false-color image of the “hurricane” at Saturn’s south pole, via NASA; the eye is estimated to be 1,250 miles wide].

“The oxygen content in the atmosphere was stable,” Pont explains, “at around 0.1 percent. This was not enough to produce an ozone layer. Therefore the stratospheric lid that kept the clouds below ten miles in the present Earth did not operate.”

This had at least one spectacular side-effect:

Convection must have extended much higher into the atmosphere. This would have been called “the Great Age of Clouds” by any visitor, since the high temperatures, large oceans and lack of stratospheric lid would have produced the most magnificent cloud formations and the most awesome storms.

Imagine standing on the shore of some rocky archipelago billions of years before any other humans were born, as massive and otherworldly storms four or five times taller than anything you’d ever seen come rolling over the horizon, torqued into strange tropical towers, flashing in every crevice with lightning to reveal vast humid interiors where air roars upward in near-permanent mushroom clouds, breaking open to reveal shells of orange and red storms within storms boiling continuously for weeks at a time. The Great Age of Clouds would be in full performance.

Pont’s book is also available through SpringerLink if you have academic access.

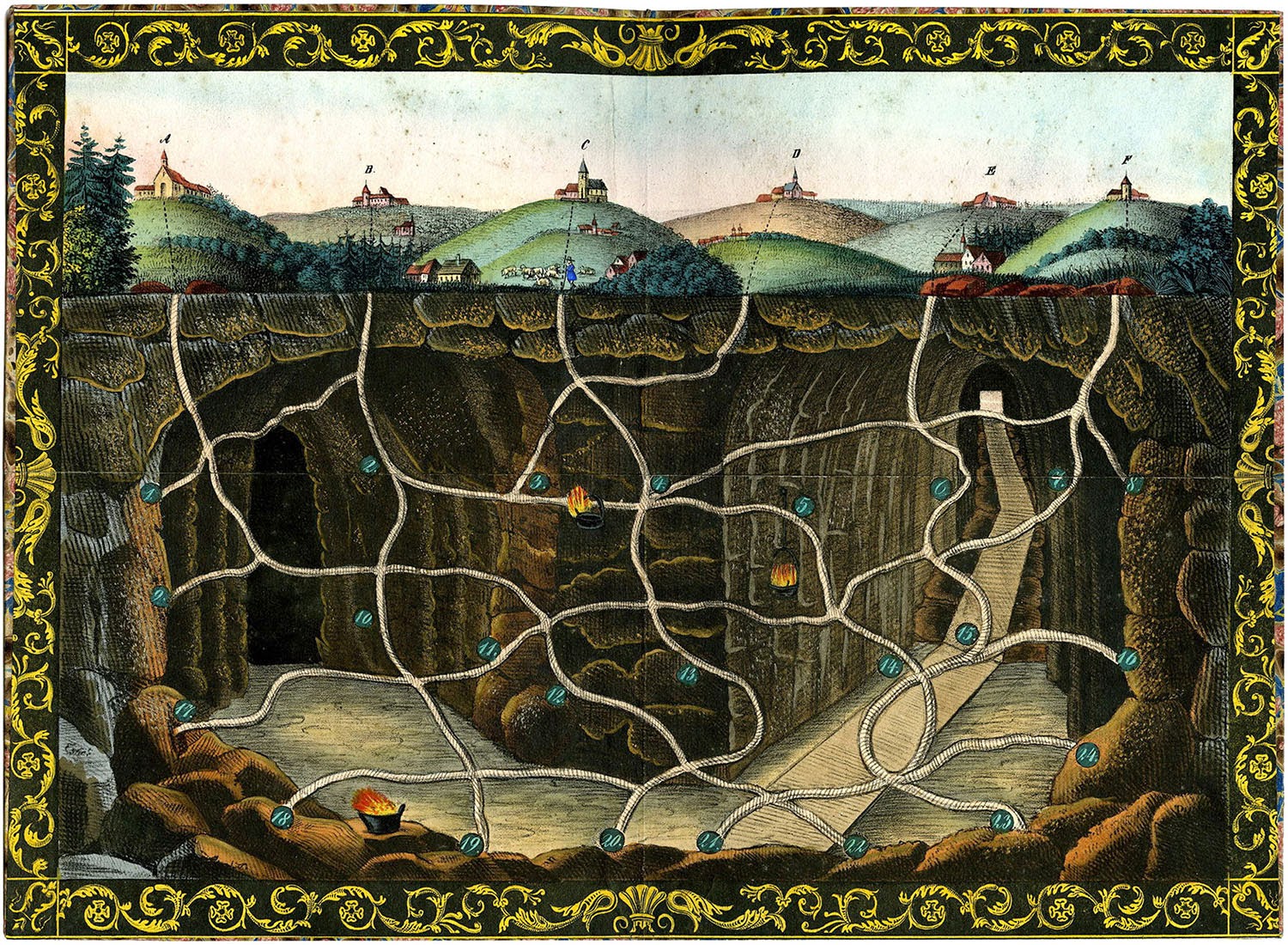

[Image: Der Bergbau, courtesy of the

[Image: Der Bergbau, courtesy of the

[Image: Screen-grab from

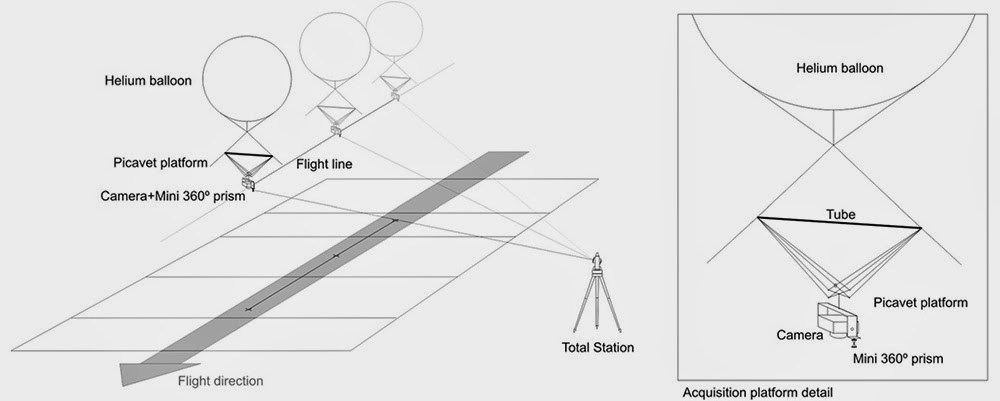

[Image: Screen-grab from  [Image: A glimpse of the balloon rig, from Mozas-Calvache et al.,

[Image: A glimpse of the balloon rig, from Mozas-Calvache et al.,  [Image: The balloon rig diagrammed, from Mozas-Calvache et al.,

[Image: The balloon rig diagrammed, from Mozas-Calvache et al.,  [Image: Some resulting images, from Mozas-Calvache et al.,

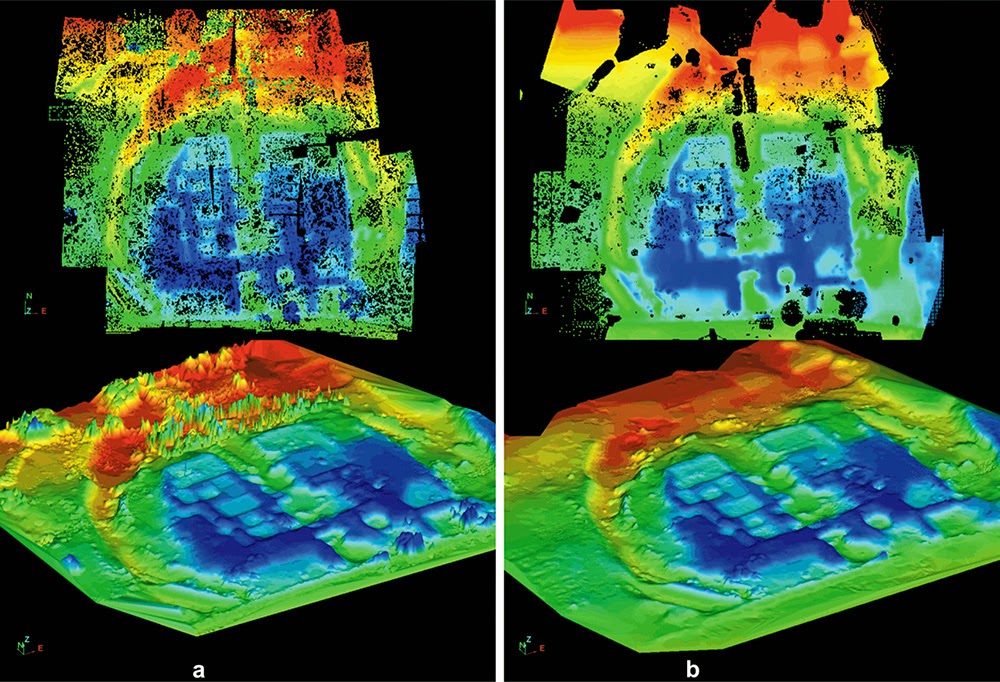

[Image: Some resulting images, from Mozas-Calvache et al.,

[Image: The

[Image: The

[Image: “Humvees are stored inside the Frigaard Cave in central Norway. The cave is one of six caves that are part of the Marine Corps Prepositioning Program-Norway, which supports the equipping of Marine Expeditionary Brigade consisting of 15,000 Marines and with supplies for up to 30 days.”

[Image: “Humvees are stored inside the Frigaard Cave in central Norway. The cave is one of six caves that are part of the Marine Corps Prepositioning Program-Norway, which supports the equipping of Marine Expeditionary Brigade consisting of 15,000 Marines and with supplies for up to 30 days.”  [Image: “Rows of front loaders and 7-ton trucks sit, gassed up and ready to roll in one of the many corridors in the Frigard supply cave located on the Vaernes Garrison near Trondheim, Norway. This is one of seven [see previous caption!] caves that make up the Marine Corps Prepositioning Program-Norway facility. All the caves total more than 900,000 sq. ft. of storage space, full of enough gear to outfit 13,000 Marines for up to 30 days.”

[Image: “Rows of front loaders and 7-ton trucks sit, gassed up and ready to roll in one of the many corridors in the Frigard supply cave located on the Vaernes Garrison near Trondheim, Norway. This is one of seven [see previous caption!] caves that make up the Marine Corps Prepositioning Program-Norway facility. All the caves total more than 900,000 sq. ft. of storage space, full of enough gear to outfit 13,000 Marines for up to 30 days.”  [Image: “Medium Tactical Vehicle Replacements, High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicles and trailers, which belong to Marine Corps Prepositioning Program-Norway are staged in a storage cave at Tromsdal, Norway, Feb. 24, 2014. Marine Corps began storing equipment in several cave sites throughout Norway in the 1980s to counter the Soviets, but the gear is now reserved for any time of crisis or war.”

[Image: “Medium Tactical Vehicle Replacements, High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicles and trailers, which belong to Marine Corps Prepositioning Program-Norway are staged in a storage cave at Tromsdal, Norway, Feb. 24, 2014. Marine Corps began storing equipment in several cave sites throughout Norway in the 1980s to counter the Soviets, but the gear is now reserved for any time of crisis or war.”  [Image: “China: ample space for a spare copy of France”; image by

[Image: “China: ample space for a spare copy of France”; image by

[Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Images: The

[Images: The  “The property comes with a 19th century fortification,

“The property comes with a 19th century fortification,

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: Another

[Image: Another  [Image: One more

[Image: One more

[Image: Screengrab from

[Image: Screengrab from  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Image: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills]. [Image: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Image: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Images: “Cultivating the Map” by Danny Wills].

[Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by

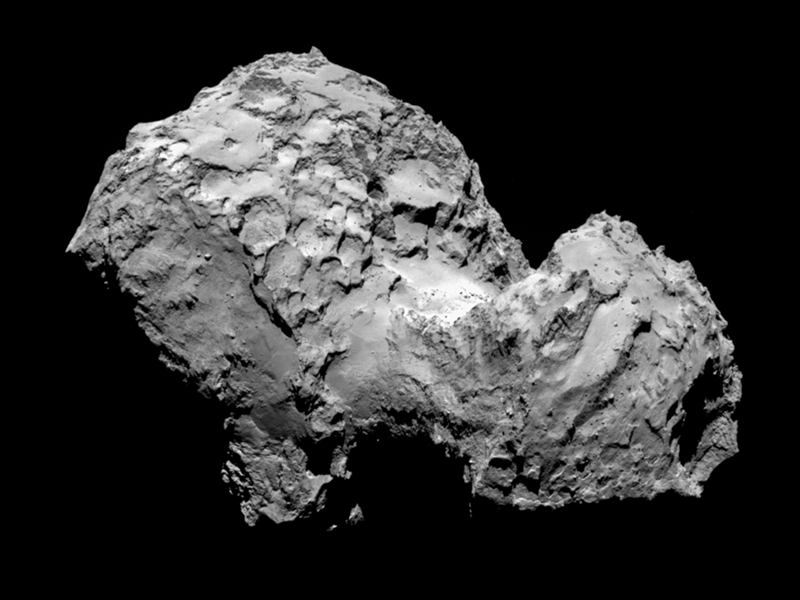

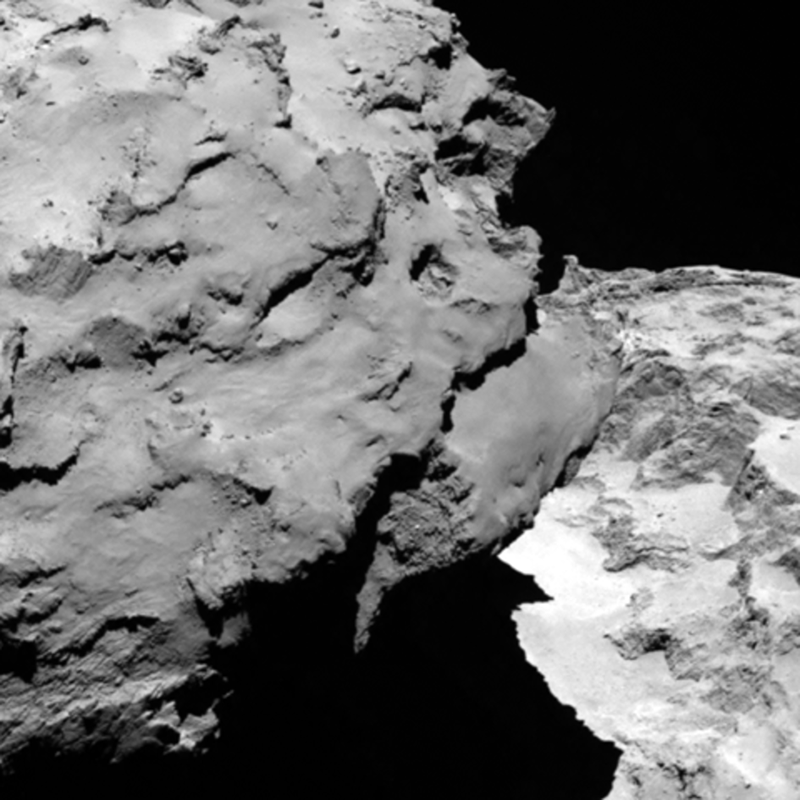

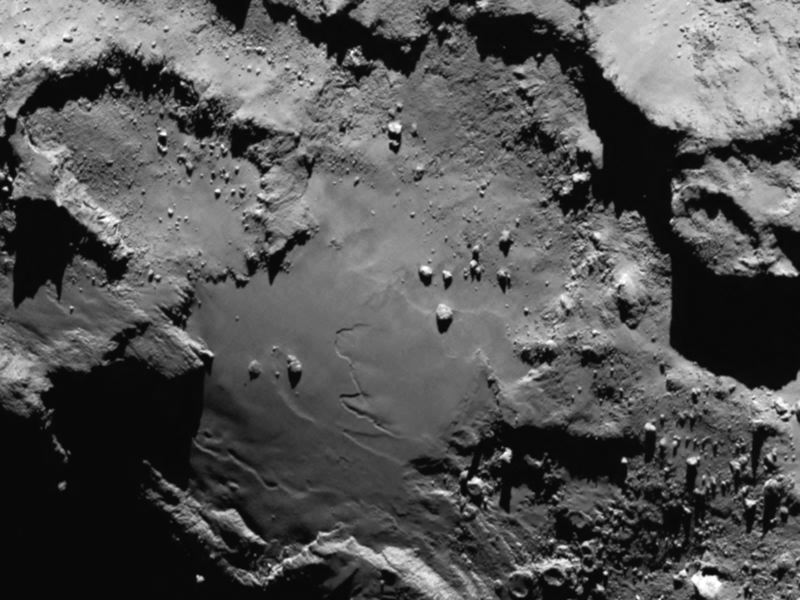

[Image: The gateway arches of the Antarctic; photo by  [Image: Approaching 67P, via the

[Image: Approaching 67P, via the