This is Part Two of a two-part interview with Mary Beard, Professor of Classics at Cambridge University and general editor of the Wonders of the World, a new series published by Profile and Harvard University Press.

Part One can be found here.

In this installment we discuss cultural authenticity and the rise of archaeo-tourism; China, the pirating of ancient history, and plaster casts of statuary; A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum; the little-understood lost lifestyle patterns of the pyroclastically entombed Pompeii; and the urban military spectacles of imperial Rome.

In this installment we discuss cultural authenticity and the rise of archaeo-tourism; China, the pirating of ancient history, and plaster casts of statuary; A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum; the little-understood lost lifestyle patterns of the pyroclastically entombed Pompeii; and the urban military spectacles of imperial Rome.

BLDGBLOG: I’d like to ask you about different cultural attitudes toward copying and historical reproduction. There’s an essay by Alexander Stille, for instance, called “The Culture of the Copy and the Disappearance of China’s Past,” where he describes how meticulous copies are often used in China as stand-ins for ancient artifacts – without that substitution being acknowledged. Stille writes that, in China, copying “is a sign of reverence rather than lack of originality.” Do you foresee any sort of interpretive conflict on the horizon between these different cultural notions of authenticity and the past?

Mary Beard: This idea, of the meticulous copy being used as a stand-in for the ancient artifact – and that, somehow, this substitution can be its own historical object – well that’s one we actually find our own past. It’s not just a Chinese thing.

I’ve been thinking recently about the role of the plaster cast, and about collections of plaster casts; and, in a sense, it seems to me that the cult of the plaster cast, in seventeenth to early mid-nineteenth century Europe, had much in common with what Stille’s describing in China. Now – and I mean since the total commitment within modernism to “authenticity” – we regard plaster casts as cheap and perhaps awkward copies of the original. But, certainly, in the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, plaster casts were the object that provided people with “real” connection with the classical world. The plaster cast was, in a sense, the fount of classical art and classical knowledge, and people like Goethe were inspired not so much by what we would think of as the authentic marble object, but by looking at plaster casts.

At one point in the Parthenon book – I mention it just very briefly – there was a moment, in the 1930s, when the British Museum had got all of Elgin’s marbles there, but the bits they didn’t have they filled in with plaster casts from Greece. It wasn’t that the casts were actually valued the same, but that viewers could happily see these things, side by side, in order to experience the Parthenon sculptures.

I think it’s actually quite moving sometimes, reading people’s accounts of Greek and Roman sculpture in the eighteenth and nineteenth century – because they’re describing plaster casts using a language which we would not now use for copies. They’re not framing it as a copy – they’re framing it as if it was it – or at least as if was sufficiently like the “real thing” to be able to prompt some of the same language and emotions.

[Image: A view of the Elgin Marbles, via the Wik].

[Image: A view of the Elgin Marbles, via the Wik].

BLDGBLOG: That seems to be as much about the desire to encounter the thing itself as to use convenient stand-ins for that thing, when “authenticity” is simply too expensive to afford.

Mary Beard: That’s partly it – but one thing that’s curious is that the modern city of Rome produced and displayed loads of plaster casts until quite recently (and there is still a great collection in the University gallery in Rome). They went in for making plaster casts of sculpture when they’d got the real stuff sitting right there in front of them. “Authenticity” is always a trickier idea than we think it is – which is, I guess, one of the things that “post-modernism” has been about telling us.

BLDGBLOG: Do you see educational value in things like merchandising, then? Do souvenirs obscure the past or give people access to it?

Mary Beard: I tend to be pretty laid back about it. I mean, I can do the argument about commodification if you like. I can say: goodness me, what you are doing? You’re re-presenting a tawdry cheap object, to make a vast amount of profit, and it’ll be bought by somebody else in the belief that, somehow, they have just bought into cultural property. I can do the gloomy side of it.

But I think it also goes back, more positively, to the idea that these objects are sort of shared. How do you share a monument? One of the main ways that you share a monument is by replicating it and letting people own the replica. It’s a way that people can feel they have a relationship to the original. That’s been going on since antiquity itself. One of the things that’s quite extraordinary is the number of relatively small-scale replicas there are of the cult statue of Athena from the Parthenon – hundreds of them.

Of course, in some ways, you say, tourists are being palmed off with plastic souvenirs instead of with knowledge – and, of course, some of these things, the middle class cultural critics can say, are horrible and cheap, and people think they’re buying culture when, in fact, they’re buying a nasty little replica. Obviously there’s an ambivalence there, but it never seems to me to be wholly bad.

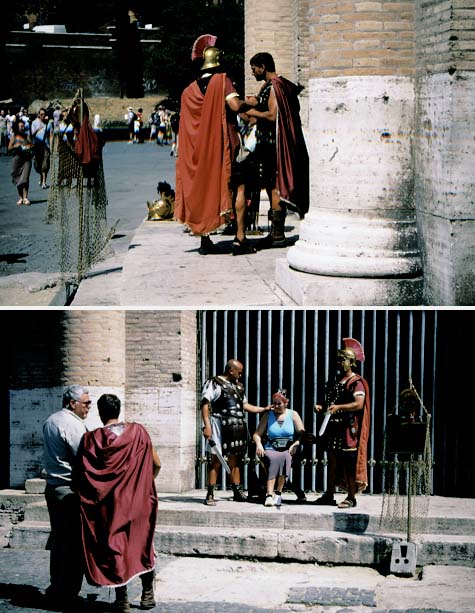

You know, you have your photograph taken at the Colosseum next to somebody dressed up like a gladiator. Is that a terrible bit of exploitation because you’ve just paid a ridiculous amount of money? Well, that’s exactly what it is in one way – but it’s also a way of writing yourself into the history of that site, and saying “I was there.”

[Images: Tourists having their picture taken “next to somebody dressed up like a gladiator.” Photo by Robin Cormack].

[Images: Tourists having their picture taken “next to somebody dressed up like a gladiator.” Photo by Robin Cormack].

BLDGBLOG: For a lot of people, there’s also a sense of irony there – in the idea that you’d get your picture taken next to a gladiator. It’s like a joke: look at me, wearing shorts, standing next to an Italian guy dressed like a gladiator.

Mary Beard: Yes, that’s right. I don’t think one’s capacity for self-ironization is necessarily incompatible with the idea of ownership. When I buy my ouzo bottle shaped like the Parthenon, it’s another way to the same end.

We tend to think that tourists are dupes being flogged crap which they don’t realize is crap. Actually, I suspect that most people, like you and I, do realize that it’s crap. The point is to buy crap, because that’s part of what the deal is – that’s the transaction which you’re doing.

I suppose it’s all part of what I’m thinking in general: people are much smarter about their engagement with these places than we often give them credit for. They/we have quite a highly developed sense of what the touristic game is all about. I might be an expert when it comes to the Parthenon, but I go to hundreds of places where I know nothing at all – but I still know what the contract is, between the tourist and the monument.

[Images: The streets of Pompeii, via Wikipedia].

[Images: The streets of Pompeii, via Wikipedia].

BLDGBLOG: This changes the subject a bit, but I understand you’re also writing a new book about Pompeii. Is that for the Wonders for the World?

Mary Beard: I am writing a Pompeii book, and it’s for Profile and Harvard, like the Wonders. However, it’s not in the series because it’s going to be rather longer than that – and there’s a practical consideration here. If you’re going to tell your authors not to do more than 50,000 words, then you can’t have the series editor deciding she wants to do 100,000 words!

I suppose I’m trying to do some quite specific things. I’ve worked on and off on Pompeii for 20 or 30 years, and it struck me that, apart from the study of volcanology (where everybody will talk till the cows come home about “pyroclastic flows” and all that), by and large there’s an increasing gap between what academic studies of Pompeii are doing and the kind of stuff that popular books on Pompeii feed people. I wanted to see if I could close a bit of that gap between what people normally get given, if they’re not specialists, and some of the ways of thinking about the city that are current within academic debate.

I think that one of the problems about going to Pompeii, once you’ve done your first wander round it – and, even now, it’s gob-smacking to go to the ancient town – there’s a question of: what do people look at? And how do they look at it?

I think, as we were saying before, tourists are pretty canny – but their canniness and sharpness is often crushed by the sense that there is a particular set of questions that are somehow the right questions to ask. I suppose I want to help people see that their puzzlement about how this town worked – their puzzlement about the city – is legitimate. You know, they should go on asking those kinds of questions.

There is a huge distance between us and what went on in this town (whatever that was); yet, on the other hand, there is a dialogue that you can have with it. It’s a dialogue which is, in part, mediated by novels and films and so on – Last Days of Pompeii and the like. And that is something we have to work through, not against. It’s that way of thinking I’m interested in exploring.

BLDGBLOG: You’ve written on your blog about Pompeii’s ancient traffic patterns, and about some more mundane questions, such as how Pompeii actually functioned.

Mary Beard: Yes, that’s right – you know: where did people go to the loo? Why is there so little “stuff” there? Why was so little found in Pompeii? Well, that really is interesting – and that is what archaeologists are sometimes honest enough to worry about. Where do these stairs actually go? Did anything happen up there? How many people lived here?

So you want to say to tourists: your questions aren’t foolish. We don’t know what the upstairs was like. Estimates of the population of Pompeii vary by thousands, according to whether you think all the slaves lived up there, squashed together in dorms, or whether there were some elegantly spacious master bedrooms, or whether it was mostly storeroom. We really don’t know. We don’t even know how Pompeii related to the sea!

But I think there is a very difficult trade-off here. In the end it’s a terrible downer for people always to say, “We don’t know, we don’t know, we don’t know.” You’ve got to tell them something that we do know!

I suppose I want to write a book that doesn’t fob people off with simplifying stories that I know not to be true. I think that’s the nasty power relationship between popular books on the ancient world and their readers: an author, who knows how complicated it is, tells the ignorant reading public a simplified story that he or she doesn’t really believe. That then makes writing – and disseminating what you know about the ancient world – an act of bad faith. So you want it to be good faith – without saying: the conclusion of this book is that we know nothing.

BLDGBLOG: [laughs] That reminds me of Robert Irwin’s book, where he begins with two full pages’ worth of incorrect “facts” about the Alhambra.

Mary Beard: Yes. Jolly good.

[Images: A Triumph through the streets of Rome following the sack of Jerusalem. For more on Roman Triumphs, don’t miss Mary Beard’s forthcoming book; for more on the sack of Jerusalem, grab a copy of Simon Goldhill’s The Temple of Jerusalem].

[Images: A Triumph through the streets of Rome following the sack of Jerusalem. For more on Roman Triumphs, don’t miss Mary Beard’s forthcoming book; for more on the sack of Jerusalem, grab a copy of Simon Goldhill’s The Temple of Jerusalem].

BLDGBLOG: You’ve also got another forthcoming book, published by Harvard, about the Roman Triumph – about Roman military processions. Could you tell me more about that? Is it similar in tone to the Wonders of the World series?

Mary Beard: In a funny way, although it’s a longer book, and it’s heavily footnoted, it’s written partly for the same kind of audience. It’s for the specialist as well as the intelligent ignorant.

What the book is saying is: look, here is a Roman ceremony which, much in the same way as these monuments, has been reworked and reappropriated throughout history. You know, Napoleon does the Triumph, every blasted princeling in the Renaissance does a Triumph, Mantegna paints the Triumph – it’s still a cultural form that we share with the Romans. So how can we make sense of it? Particularly now, how do we think about celebrating military victory – and what form is possible, legitimate, in bad taste, in good taste…?

This relates, of course, to how we now package the Romans. Certainly for the last hundred years or so, they have been seen as the poor relations of the Greeks: Greek culture, we believe, was intellectual and self-reflexive, whilst the Romans were thugs who built roads and won battles. It’s a convenient dyad for us but, in many ways, it undermines and disguises so much of what’s really interesting about Roman culture.

One of the things I’m wanting to say about the Triumph goes like this. Here you’ve got the most fantastic parade ever of Roman wealth and imperialism. The Romans score disgustingly big victories, massacring thousands, and they come and celebrate it in the center of the city, bringing the prisoners and the spoils and the riches and all the rest. At one level, this is a jingoistic, militaristic display that would warm the heart of every European dictator ever after – but, at the same time, scratch the surface of that. Look at how the Romans talked about it. That very ceremony is also the ceremony in which you see the Romans debating and worrying about what glory is, what victory is. Who, really, has won? It’s a ceremony that provides Rome with a way of thinking about itself. It exposes all kinds of Roman intellectual anxieties.

For example, there are constant anecdotes, which I think are very loaded anecdotes, about how risky a celebration it is, and how the celebration can always go wrong. There’s one General, Pompey, in the sixties BC, who decides to outbid all of the previous triumphant Generals. Instead of having his chariot yoked to horses, he decides to have it pulled by elephants. It looks fantastic – it looks kind of divine (that’s how the god Bacchus drove his chariot) – until he comes to go through an arch and the elephants get stuck in the arch. So he reverses a bit, and he tries it again – and they still can’t get through. They finally have to unhitch the elephants and bring up the horses – and you think: why is this anecdote being told? Not only is this obviously a humiliating moment – wouldn’t you feel a real fool if it happened to you! – but it’s also being told as a way of saying, remember, glory has to be carefully negotiated. Where is the boundary between glory and foolishness?

Another question is: who do you look at when you’ve got this great procession? Who’s the star of the show? Is it the General in his chariot? Well, sometimes it is – but sometimes it’s the victims. Sometimes military victory makes stars of the defeated. That was also a problem in the gladiatorial arena: who was the star? Well, it was the gladiator, not the emperor. In the Triumph those exotic but pathetic captives regularly stole the show, or were said to, and Roman poets and historians recognized this, and wondered about it, and played with it, and they turned it into a metaphor just like we do. And that is so topical today. Take Saddam Hussein’s execution – you know, what was the upshot of those films? Who won?

Militarism often goes hand in hand with everything which undermines militarism. The Romans were actually – if you know how to read them right, and if you’re not expecting them to be Greek and to talk about it in the same way – they’re actually looking at the nature of military victory, and military display, and they’re wondering about it some of the same ways that we do.

So that’s what the book is about – or, at least, those are some of the questions that have driven it.

[Images: A poster for 300 and scenes from 300 and Gladiator].

[Images: A poster for 300 and scenes from 300 and Gladiator].

BLDGBLOG: Finally, could you talk a bit about the present state of pop cultural knowledge about the Classical world, from the film 300 and David Beckham’s new tattoo to cable television documentaries? In the most general sense, are these things useful for teaching the Classics?

Mary Beard: I’m very keen on it, of course. I have to be. Partly, you know, if you’re a classicist teaching Classics at a British university, self-interest is a factor here. All these things, from Gladiator on, have been a tremendous recruiting ground, and so we go around talking about whether Gladiator’s true or not, and 300, and all the rest – and encouraging people to get interested in “real” Classics that way (there, I’m talking about authenticity!).

More generally, though, one of the things that these movies and so on remind us is that classical culture simply isn’t the bastion of elitism that it’s often made out to be. Certainly in the UK – and, I expect, it’s largely the same in the U.S. – the study of Classics, as an academic discipline, is thought to be the upper echelons of privilege and elitism. To some extent that’s true – and to some extent it’s unfair. What that view overlooks is the fact that there has been enormous amounts of mass engagement with ancient culture from the end of the 19th century onwards. Books like The Last Days of Pompeii, or Ben-Hur, sold fantastic quantities. They were absolute bestsellers, in the way that Gladiator is a bestselling movie.

What’s interesting though is that every generation has always claimed that it was the first to rediscover the Romans for themselves, and for mass culture. You can see that very clearly with the Broadway musical, A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum. It was a fantastic success, but it sold itself in very similar terms to Gladiator – that here, for the first time, the wee masses were going to see Rome as it really was.

So what interests me, beyond the hope that this brings other people into Classics, is the idea that Classics is a subject which is actually quite democratic. It isn’t only this kind of toff, upper-class subject it’s often thought to be. Every generation enjoys rediscovering it – but, each time it comes around, we claim that now, for the first time, we’ve got privileged knowledge which we’re going to share with you all over again. In fact, there are hundreds and hundreds of movies, and hundreds of novels, and thousands of cartoon strips about the Romans. They never go away – but we always think that it’s us that got them first.

In the UK, when kids discover Asterix the Gaul – a wonderful cartoon series about plucky little Gauls fighting the Romans – each 10-year old finds it anew, and rediscovers the Romans for themselves. Which is just how it should be.

[Image: The Colosseum, photographed by Robin Cormack].

[Image: The Colosseum, photographed by Robin Cormack].

I owe a huge thank you to Mary Beard for taking the time to have this conversation, and for following up with images and with edits to the transcript.

For more Mary Beard, meanwhile, don’t miss her blog, A Don’s Life; her essays at the London Review of Books; or The Roman Triumph, due out this Autumn.

Finally, titles in the Wonders of the World series now include:

The Parthenon by Mary Beard

The Colosseum by Keith Hopkins and Mary Beard

The Tomb of Agamemnon by Cathy Gere

The Temple of Jerusalem by Simon Goldhill

Westminster Abbey by Richard Jenkyns

The Alhambra by Robert Irwin

The Rosetta Stone by John Ray

St. Peter’s by Keith Miller

St. Pancras Station by Simon Bradley

The Memorial to the Missing of the Somme by Gavin Stamp

Collect them all—and don’t miss Part One of this interview while you’re doing so.

A few notable titles in that series include Mary Beard’s own book about

A few notable titles in that series include Mary Beard’s own book about

BLDGBLOG: When it comes to choosing an author to produce these books, do you go after people whose scholarly work you already admire – or do the authors come looking for you, pitching you ideas for a new monument or Wonder?

BLDGBLOG: When it comes to choosing an author to produce these books, do you go after people whose scholarly work you already admire – or do the authors come looking for you, pitching you ideas for a new monument or Wonder? [Image: The interior iron arches of London’s St. Pancras Station, via

[Image: The interior iron arches of London’s St. Pancras Station, via  [Image: Tourists visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau; photo via

[Image: Tourists visiting Auschwitz-Birkenau; photo via  BLDGBLOG: Most of the books now focus on sites around the Mediterranean – with some exceptions, but those exceptions are all European. Do you see the series going on to include non-European sites like Macchu Picchu or the Taj Mahal?

BLDGBLOG: Most of the books now focus on sites around the Mediterranean – with some exceptions, but those exceptions are all European. Do you see the series going on to include non-European sites like Macchu Picchu or the Taj Mahal? BLDGBLOG: I thought Cathy Gere’s book,

BLDGBLOG: I thought Cathy Gere’s book,  BLDGBLOG: I think a lot of this, though, comes down to the specific historical relationship between the countries involved. The U.S. having British artifacts in a museum means one thing, whereas, say –

BLDGBLOG: I think a lot of this, though, comes down to the specific historical relationship between the countries involved. The U.S. having British artifacts in a museum means one thing, whereas, say – [Image: Benito Mussolini, via

[Image: Benito Mussolini, via  [Image: The Arch of Titus, via

[Image: The Arch of Titus, via  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The Memorial Park Storage Chambers in Toronto’s

[Image: The Memorial Park Storage Chambers in Toronto’s  [Image: “Stairs” by Michael Cook, from the

[Image: “Stairs” by Michael Cook, from the

[Images: (top) “Transition to CMP,” from Toronto’s

[Images: (top) “Transition to CMP,” from Toronto’s  [Image: “Emerging in Wilson Heights,” out of Toronto’s

[Image: “Emerging in Wilson Heights,” out of Toronto’s  [Image: The outfall of Toronto’s

[Image: The outfall of Toronto’s  [Image: An “A-shaped conduit” in Toronto’s

[Image: An “A-shaped conduit” in Toronto’s

[Image: (top) “Outfall structure in the West Don Valley,” part of Toronto’s

[Image: (top) “Outfall structure in the West Don Valley,” part of Toronto’s  [Image: “Outfall in winter” at Toronto’s

[Image: “Outfall in winter” at Toronto’s  [Image: Looking out of a spillway at the

[Image: Looking out of a spillway at the  [Image: The “spectacular, formerly natural waterfall that the [

[Image: The “spectacular, formerly natural waterfall that the [ [Images: A “short drop” in Toronto’s beautifully torqued and ovoid

[Images: A “short drop” in Toronto’s beautifully torqued and ovoid

[Images: Four glimpses of the vaulted topologies installed inside the Earth at Niagara’s

[Images: Four glimpses of the vaulted topologies installed inside the Earth at Niagara’s

[Images: (top) Leaving the

[Images: (top) Leaving the  [Image: “Transitions” inside the

[Image: “Transitions” inside the  [Image: “Deep inside the century-old wheelpit that is the beginning of the

[Image: “Deep inside the century-old wheelpit that is the beginning of the  [Image: Ottawa’s

[Image: Ottawa’s  [Image: “Looking into the bottom of the William B. Rankine G.S. wheelpit from

[Image: “Looking into the bottom of the William B. Rankine G.S. wheelpit from  [Image: Inside a distributor tunnel at the

[Image: Inside a distributor tunnel at the

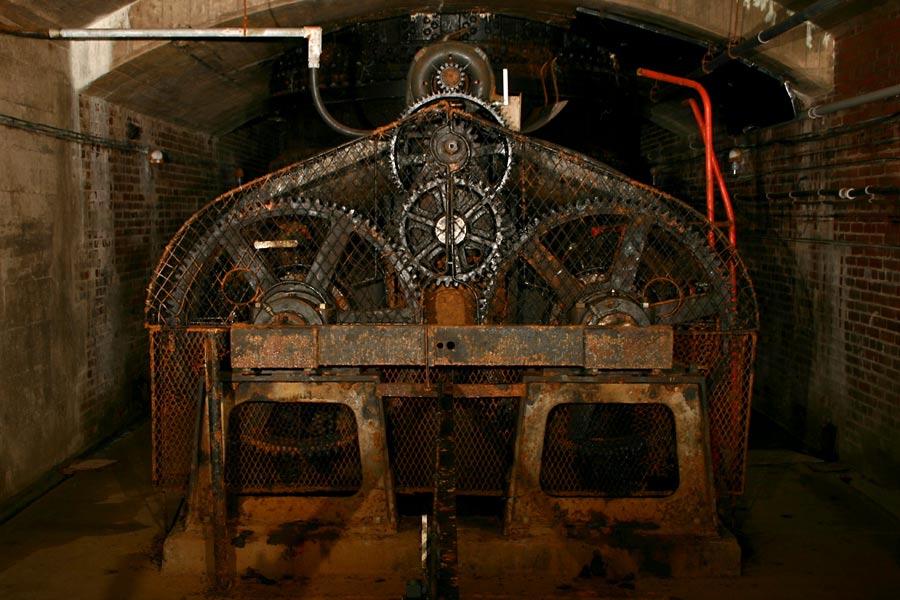

[Images: Disused hydroelectric machinery:

[Images: Disused hydroelectric machinery:  [Image: Abandoned cash registers].

[Image: Abandoned cash registers]. [Image: Inside

[Image: Inside  [Image: The “

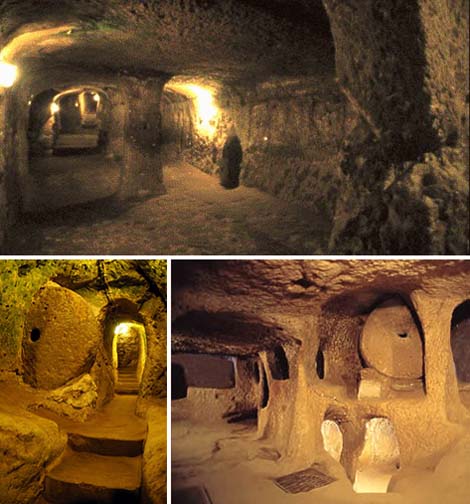

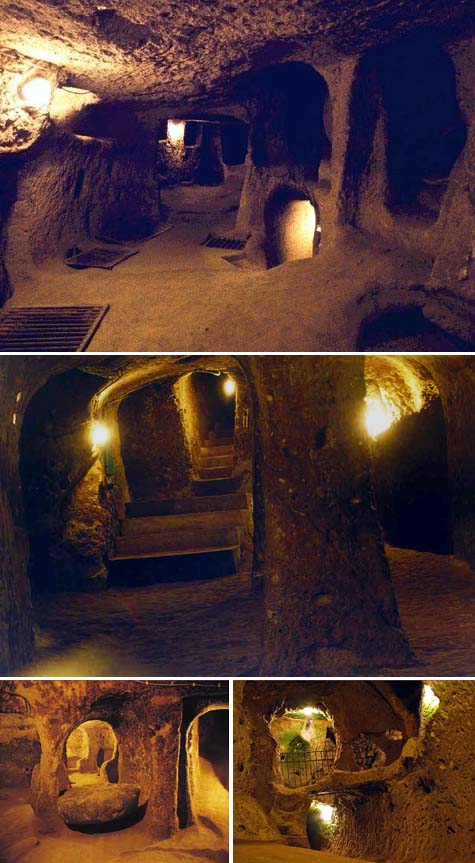

[Image: The “ [Images: Derinkuyu, the great underground city of Cappadocia; images culled from a

[Images: Derinkuyu, the great underground city of Cappadocia; images culled from a  [Images: Derinkuyu, the great underground city of Cappadocia; images culled from a

[Images: Derinkuyu, the great underground city of Cappadocia; images culled from a  [Images: Derinkuyu and a view of Cappadocia; images culled from a

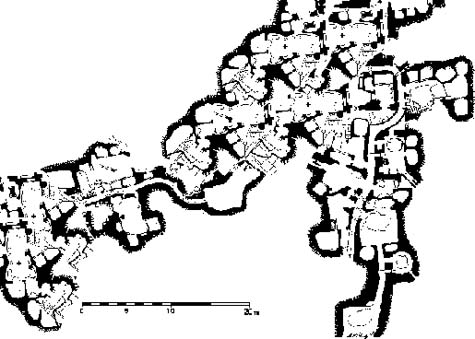

[Images: Derinkuyu and a view of Cappadocia; images culled from a  [Image: A map, altered by BLDGBLOG, of an underground Cappadocian metropolis].

[Image: A map, altered by BLDGBLOG, of an underground Cappadocian metropolis]. [Image: Ole Bouman, photographed by Cassander Eeftinck Schattenkerk].

[Image: Ole Bouman, photographed by Cassander Eeftinck Schattenkerk]. BLDGBLOG: In

BLDGBLOG: In  BLDGBLOG: Again in

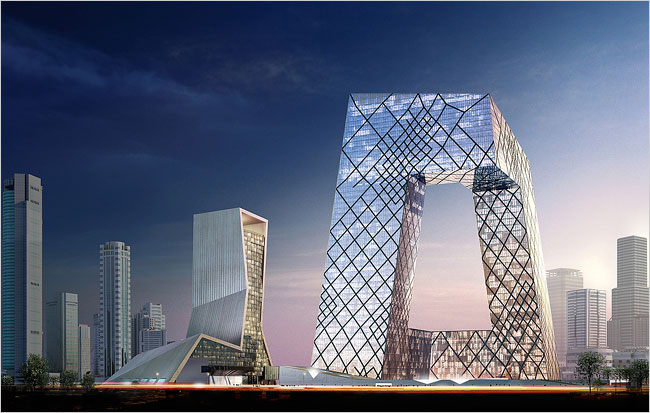

BLDGBLOG: Again in  [Image: The CCTV building, Beijing, by Rem Koolhaas/

[Image: The CCTV building, Beijing, by Rem Koolhaas/ BLDGBLOG: I’m interested in your work – and

BLDGBLOG: I’m interested in your work – and  BLDGBLOG: When you go there, who exactly are you networking with? Architects? Civil servants?

BLDGBLOG: When you go there, who exactly are you networking with? Architects? Civil servants?

BLDGBLOG: Finally, as far as your new job goes – becoming

BLDGBLOG: Finally, as far as your new job goes – becoming  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: An artificial waterfall below the surface of the earth, photographed by

[Image: An artificial waterfall below the surface of the earth, photographed by  [Image: Tower of ladders and platforms, photographed by

[Image: Tower of ladders and platforms, photographed by  [Image: Black and white topology of intake valves, photographed by

[Image: Black and white topology of intake valves, photographed by

[Images: The human encounter with geometry by torchlight, photographed by

[Images: The human encounter with geometry by torchlight, photographed by  [Image: Instrumental curvature, photographed by

[Image: Instrumental curvature, photographed by  [Image: Shining tunnelwork of the future, photographed by

[Image: Shining tunnelwork of the future, photographed by  [Image: (Right) Ed Mazria, photographed by Doug Hoeschler for

[Image: (Right) Ed Mazria, photographed by Doug Hoeschler for  [Image: A chart of Architecture 2030’s goals; via

[Image: A chart of Architecture 2030’s goals; via  [Image: “U.S. Energy Consumption by Sector. A reorganization of existing data – combining the energy required to run residential, commercial, and industrial buildings along with the embodied energy of industry-produced materials like carpet, tile, and hardware – exposes architecture as the hidden polluter.” Graphic by Criswell Lappin, via

[Image: “U.S. Energy Consumption by Sector. A reorganization of existing data – combining the energy required to run residential, commercial, and industrial buildings along with the embodied energy of industry-produced materials like carpet, tile, and hardware – exposes architecture as the hidden polluter.” Graphic by Criswell Lappin, via  [Image: The interior of Ed Mazria’s New Mexico home, designed by

[Image: The interior of Ed Mazria’s New Mexico home, designed by  [Image: Skylit gymnasium in Genoveva Chavez Community Center, Santa Fe; designed by

[Image: Skylit gymnasium in Genoveva Chavez Community Center, Santa Fe; designed by  BLDGBLOG: The

BLDGBLOG: The  [Image: Materials Testing Facility, Vancouver, designed by

[Image: Materials Testing Facility, Vancouver, designed by  [Image: School of Nursing and Student Community Center, Houston, designed by

[Image: School of Nursing and Student Community Center, Houston, designed by  [Image: Energy Savings Buildings, Albuquerque; designed by

[Image: Energy Savings Buildings, Albuquerque; designed by  [Image: “Chat piles” looming round the “abandoned storefronts and empty lots” of Picher, OK; photo by

[Image: “Chat piles” looming round the “abandoned storefronts and empty lots” of Picher, OK; photo by  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Circle Line Pinhole 16, from

[Image: Circle Line Pinhole 16, from  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image: