[Image: “Guatemala Tikal D8006” by youngrobv].

[Image: “Guatemala Tikal D8006” by youngrobv].

Easily one of the most interesting things I’ve read in quite a while is how a team of particle physicists from UT-Austin plan on using repurposed muon detectors to see inside Mayan archaeological ruins.

In the new issue of Archaeology, Samir S. Patel describes how “an almost featureless aluminum cylinder 5 feet in diameter” that spends its time “silently counting cosmic flotsam called muons” – “ghost particles” that ceaselessly rain down from space – will be installed in the jungles of Belize.

There, these machines will map the otherwise unexplored internal spaces of what the scientists call a “jungle-covered mound.”

In other words, an ancient building that now appears simply to be part of the natural landscape – a constructed terrain – will be opened up to viewing for the first time since it was reclaimed by rain forest.

It’s non-invasive archaeology by way of deep space.

[Images: The muon detector, courtesy of the UT-Austin Maya Muon Group].

[Images: The muon detector, courtesy of the UT-Austin Maya Muon Group].

From the UT-Austin Maya Muon Group website:

The first major experiment of the Maya Muon Group will bridge the disciplines of physics and archeology. The particle detectors and related systems are designed specifically to explore ruins of a Maya pyramid in collaboration with colleagues at the UT Mesoamerican Archaeological Laboratory. The Maya Muon Group will travel to La Milpa in northwest Belize to make discoveries about “Structure 1” – a jungle-covered mound covering an unexplored Maya ruin.

Pointing out that dense materials block more muons, Patel explains that a muon detector can actually detect rooms, spaces, and caves inside what seems to be solid:

A detector next to a Maya pyramid, for example, will see fewer particles coming from the direction of the structure than from other angles: a muon “shadow.” And if a part of that pyramid is less dense than expected – containing an open space for, say, a royal burial – it will have less of a shadow. Count enough muons that have passed through the pyramid over the course of several months, and they will form an image of its internal structure, just like light makes an image on film. Then combine the images from three or four devices and a 3-D reconstruction of the pyramid’s guts will take shape.

Referring to a muon detector already at work on the campus of UT-Austin, Patel writes: “The detector sees in every direction, so it also records muon shadows from the adjacent university buildings, and can even identify empty corridors. Silently, with little tending, it takes a monumental x-ray of the world around it.”

“The resulting image,” he adds, “will be almost directly analogous to a medical CAT-scan.”

[Image: The muon detector, courtesy of the UT-Austin Maya Muon Group].

[Image: The muon detector, courtesy of the UT-Austin Maya Muon Group].

Install one of these things in New York City and see what you find: moving blurs of elevators and passing trucks amidst the strange, skeletal frameworks of skyscrapers that stand behind it all in a labyrinthine mesh.

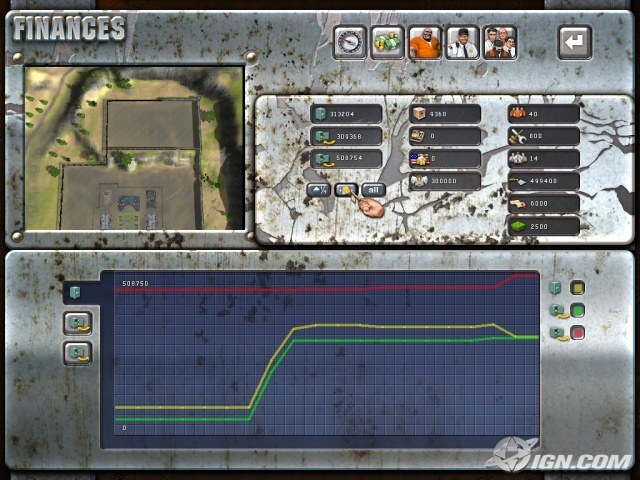

[Image: A diagram of how it all works; from this PDF by Roy Schwitters].

[Image: A diagram of how it all works; from this PDF by Roy Schwitters].

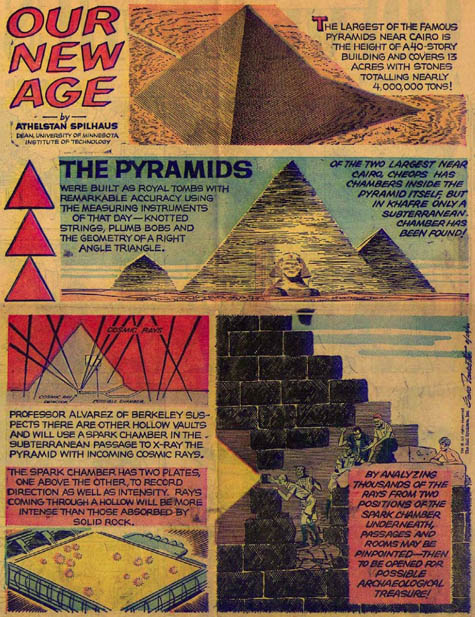

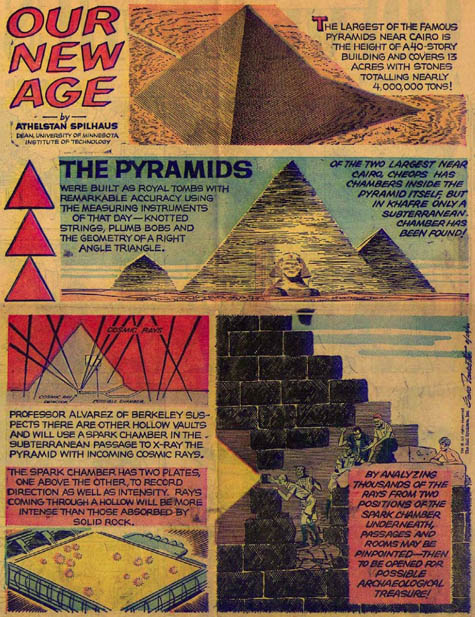

Patel goes on to relate the surreal story of physicist Luis Alvarez, who used muons “to scan the inside of an ancient structure” – in this case, Khafre’s pyramid at Giza. “Working with Egyptian scientists in the late 1960s,” we read, “he gained access to the Belzoni chamber, a humid vault deep under the pyramid.”

Like something out of an H.P. Lovecraft story, “Alvarez’s team set up a muon detector called a spark chamber, which included 30 tons of of iron sheeting, in the underground room.”

Foreign physicists building iron rooms beneath the pyramids! To search for secret chambers based on the evidence of cosmic particles.

[Image: An illustrated depiction of Luis Alvarez’s feat; view larger!].

[Image: An illustrated depiction of Luis Alvarez’s feat; view larger!].

Indeed, we read:

Suspicion of the research team ran high – here was a group of Americans with high-tech electronics beneath one of Egypt’s most cherished monuments. “We had flashing lights behind panels – it looked like a sci-fi thing from Star Trek,” says Lauren Yazolino, the engineer who designed the detector’s electronics.

Alvarez’s iron room beneath the monolithic geometry of the pyramid – it’s like a project by Lebbeus Woods, by way of Boullée – apparently took one year to perform its muon-detection work.

One day, then, the team took a long look at the data – wherein Yazolino “spotted an anomaly, a region of the pyramid that stopped fewer muons than expected, suggesting a void.”

There were still undiscovered rooms inside the structure.

[Image: Wiring up the muon detector, courtesy of the UT-Austin Maya Muon Group].

[Image: Wiring up the muon detector, courtesy of the UT-Austin Maya Muon Group].

Excitingly, when Roy Schwitters sets up his muon detector next to the tree-covered mounds of the Mayan city of La Milpa, he should get his results back in less than six months. Sitting there like a strange battery, the detector’s ultra-long-term abstract photography of the jungle hillsides vaguely reminds me of the technically avant-garde photographic work of Aaron Rose.

Rose has pioneered all sorts of strange lenses and unexpected chemical developers as he takes long-term exposures of Manhattan.

New York becomes less a city than a kind of impenetrable wall of built space.

[Images: Four photographs by Aaron Rose. View slightly larger].

[Images: Four photographs by Aaron Rose. View slightly larger].

Again, then, I’m curious what it’d be like to install one of these muon detectors in Manhattan: the shivering hives of space it might detect, as delivery trucks shake the bridges and elevators move up and down inside distant high-rises. What would someone like Aaron Rose be able to do with a muon detector?

Are muon detectors the future of urban art photography?

Perhaps it could even be a strange new piece of public art: a dozen muon detectors are installed in Union Square for six months. They’re behind fences, and look sinister; conspiratorialists leave long comments on architecture blogs suggesting that the muon detectors might not really be what they seem…

But the resulting images, after six months of Manhattan muon detection, are turned over as a gift to the city; they are hung in massive prints inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art, near the Egyptian wing, and Neil deGrasse Tyson delivers the keynote address.

Or perhaps a muon detector could be installed atop London’s fourth plinth:

The Fourth Plinth is in the north-west of Trafalgar Square, in central London. Built in 1841, it was originally intended for an equestrian statue but was empty for many years. It is now the location for specially commissioned art works.

For six months, a shadowy muon detector will stand there, above the heads of passing tourists, detecting strange and labyrinthine hollows beneath government buildings where sprawling complexes from WWII spiral out of sight below ground.

Or perhaps muon detectors could even be installed along the European coast to discover things like the buried neolithic village of Skara Brae or those infamous Nazi bunkers “that lay hidden for more than 50 years” before being uncovered by the sea. As the Daily Mail reported earlier this month:

Three Nazi bunkers on a beach have been uncovered by violent storms off the Danish coast, providing a store of material for history buffs and military archaeologists.

The bunkers were found in practically the same condition as they were on the day the last Nazi soldiers left them, down to the tobacco in one trooper’s pipe and a half-finished bottle of schnapps.

So what else might be down there under the soil and the sands…?

I’m imagining mobile teams of archaeologists sleeping in unnamed instant cities in the jungles and far deserts of the world, with storms swirling over their heads, running tests on gigantic black cylinders – muon detectors, all – that stand there like Kubrickian monoliths, recording invisible flashes of energy from space to find ancient burial sites and old buildings underground.

[Images: Tikal, photographed by n8agrin: top/bottom].

[Images: Tikal, photographed by n8agrin: top/bottom].

Perhaps all the forests and deserts of the world should be peppered with muon detectors – revealing archaeological anomalies and unexpected spaces in the ground all around us.

Architecture students could be involved: installing muon detectors outside Dubai high-rises and then competing to see who can most accurately interpret the floorplan data.

[Images: “Sobrevolando Tikal, Guatemala,” photographed by Eddie von der Becke].

[Images: “Sobrevolando Tikal, Guatemala,” photographed by Eddie von der Becke].

Till one day, ten years from now, an astronaut crazed with emotional loneliness, riding through space with his muon detector, begins misinterpreting all of the data. He concludes – in a live radio transmission broadcast home to stunned mission control supervisors – that his space station has secret rooms – undiscovered rooms – that keep popping up somehow in the shadows…

More to the point, meanwhile, you can read a few more things about Roy Schwitters over at MSNBC – and, of course, at the UT-Austin Maya Muon Group homepage.

If you could design a bridge across the Bering Strait, connecting the U.S. to Russia, what would it look like? Come up with something good and you could win as much as $80,000 ($20,000, if you’re a student).

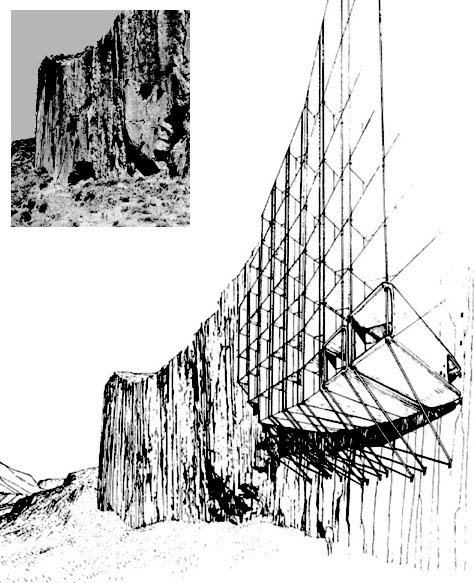

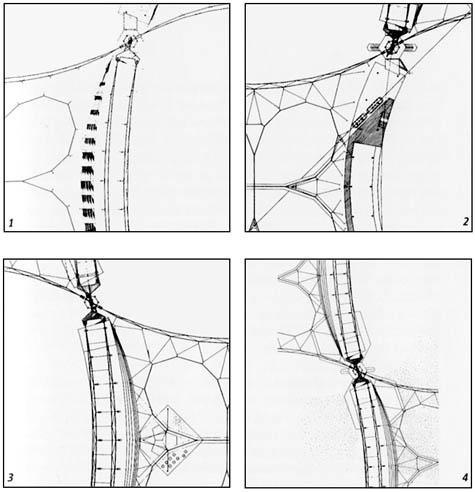

If you could design a bridge across the Bering Strait, connecting the U.S. to Russia, what would it look like? Come up with something good and you could win as much as $80,000 ($20,000, if you’re a student).  [Image: The Hanging Hotel by Takis Zenetos; think of it as the

[Image: The Hanging Hotel by Takis Zenetos; think of it as the  [Image: The Hanging Hotel, strung onto a cliffside like a musical instrument, by Takis Zenetos].

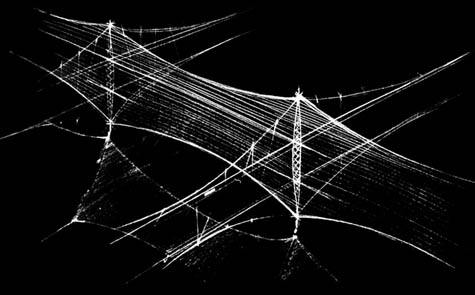

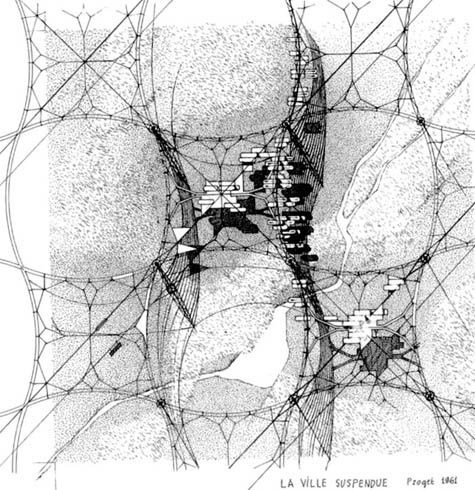

[Image: The Hanging Hotel, strung onto a cliffside like a musical instrument, by Takis Zenetos]. [Image: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos].

[Image: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos]. [Image: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos; the

[Image: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos; the

[Images: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos].

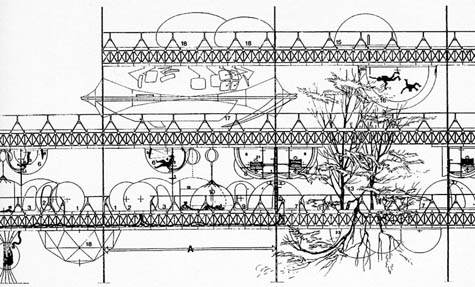

[Images: The Cable City of Takis Zenetos]. [Images: A turbined gorge by Takis Zenetos].

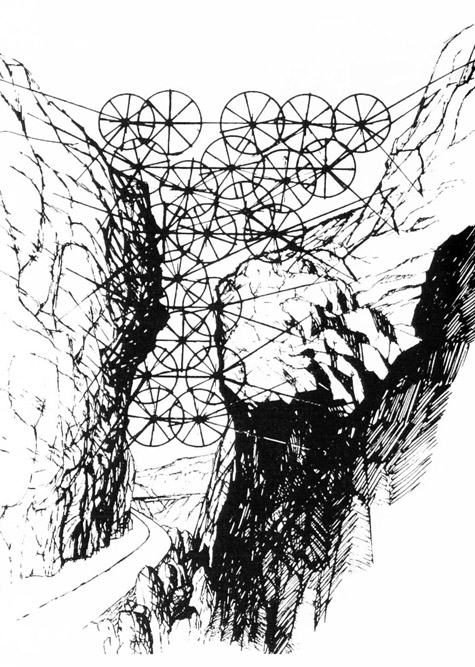

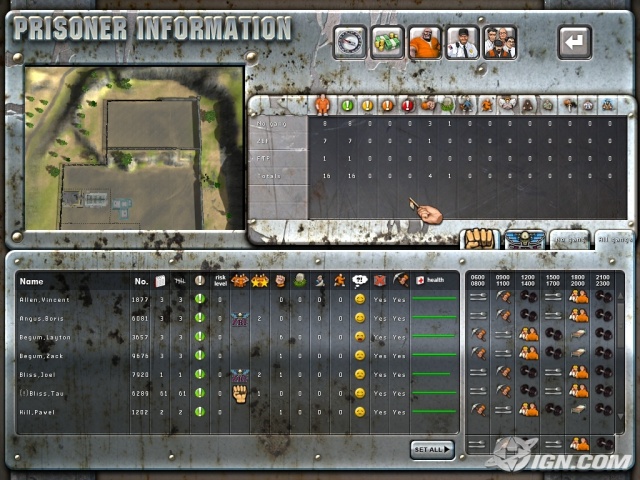

[Images: A turbined gorge by Takis Zenetos]. [Image: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. Image via

[Image: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. Image via

[Images: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. All images via

[Images: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. All images via

[Images: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. Images via

[Images: From Prison Tycoon 4: SuperMax. Images via  [Image: Offshore energy islands, via

[Image: Offshore energy islands, via  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: From Michael Winterbottom’s

[Image: From Michael Winterbottom’s  [Image: Shanghai, from

[Image: Shanghai, from  [Image: Shanghai, from

[Image: Shanghai, from  [Image: The Shanghai skyline, from

[Image: The Shanghai skyline, from  [Image: The opening titles of Michael Winterbottom’s

[Image: The opening titles of Michael Winterbottom’s  [Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Images: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Images: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by  [Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Images: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Images: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by  [Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by  [Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by

[Image: A new wing for the Museum of Photography in Charleroi by  [Image: “

[Image: “

[Images: The muon detector, courtesy of the

[Images: The muon detector, courtesy of the  [Image: The muon detector, courtesy of the

[Image: The muon detector, courtesy of the  [Image: A diagram of how it all works; from

[Image: A diagram of how it all works; from  [Image: An illustrated depiction of Luis Alvarez’s feat; view

[Image: An illustrated depiction of Luis Alvarez’s feat; view  [Image: Wiring up the muon detector, courtesy of the

[Image: Wiring up the muon detector, courtesy of the  [Images: Four photographs by

[Images: Four photographs by

[Images: Tikal, photographed by

[Images: Tikal, photographed by  [Images: “

[Images: “

[Image: The cover and a spread from

[Image: The cover and a spread from

[Image: From

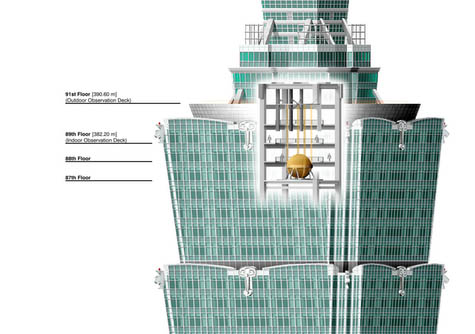

[Image: From  [Image: Diagram of Taipei 101’s earthquake ball via the

[Image: Diagram of Taipei 101’s earthquake ball via the  [Image: The 728-ton damper in Taipei 101, photographed by

[Image: The 728-ton damper in Taipei 101, photographed by  [Image: Animated GIF via

[Image: Animated GIF via