[Image: Gruen Day 2015].

[Image: Gruen Day 2015].

One of the most interestingly sinister things I studied a million years ago while writing an undergraduate thesis about shopping and agoraphobia is the so-called “Gruen transfer.”

Named after Victor Gruen, pioneer of American shopping mall design, the Gruen transfer is the moment at which, confronted by an unexpected array of choices—other products, rival goods, similar services, different options—a shopper loses sight of what he or she originally came out to purchase. That shopper originally just wanted new socks; now he wants jeans, a t-shirt, and, oh, that coffee place across the hall is looking mighty tempting right now…

The shopper’s desire has been transferred, against their will, onto another item altogether—and this transfer is a deliberately cultivated, if not entirely predictable, side-effect of how the shopping space itself has been designed.

I say “shopping space” rather than “shopping mall,” because the Gruen transfer is clearly alive and well and living online: speaking only from personal experience, the amount of random add-ons I’ve thrown into an Amazon cart at the last minute over the years, or even the extra songs I’ve bought on Bandcamp, is testament to how easy it can be to convince oneself that something you had no idea you were searching for is suddenly a must-have.

[Image: One of many malls by Victor Gruen].

[Image: One of many malls by Victor Gruen].

What was infinitely more interesting to me, however, was the fact that, when taken to an interpretive extreme, becoming hyper-aware of the possibility that the Gruen transfer might be influencing you can lead to a strange, not particularly enjoyable state of paranoia, in which every decision you make—after all, you went to the mall to buy socks, but perhaps even wanting socks was the result of a Gruen transfer, one that began in the peace of your own home, for example, when you first noticed that you would need new shoes in another month or two, only to realize that, hey, a new pair of socks right now would be awesome… You’ve been transferred.

This can be true whether or not it even involves a purchase. Making the decision to move to a new city, or going to a museum there with a new friend, or even having that new friend in your life in the first place—these all might actually be the end results of multiple, cultivated mis-steps, a much more sinister and far-reaching Gruen transfer as you were silently but comprehensively duped by the world around you.

Pushed to this level, the Gruen transfer takes on a weird, paranoid ubiquity, a disturbing omnipresence that appears to be coextensive with desire in the first place. We are, in a sense, always and already being Gruen transferred, making decisions in a state of otherwise undetectable distraction.

In any case, Victor Gruen’s spatial contribution to the American landscape—how he influenced urban form and set a multi-generational path for the design of retail environments—is the subject of a new tour hosted by the Bay Area Infrastructure Observatory. July 18, 2015, is Gruen Day 2015:

Victor Gruen (July 18, 1903–Feb 14, 1980) was an Austrian-born visionary architect most remembered for his pioneering work popularizing the enclosed, climate-controlled shopping center in the United States.

On July 18, the Bay Area Infrastructure Observatory (BAIO) invites you to celebrate the lofty aspirations and historical legacy of the suburban shopping center at Gruen Day 2015.

Festivities will include an afternoon of talks, tours, and hanging out in the food court at Bay Fair Center, which opened in 1957 as one of the first Gruen designed shopping centers in the country.

Tickets are $30—but the first ten people to email event co-organizer Tim Hwang saying that you read about the tour on BLDGBLOG will get a free ticket. Email him at tim (at) infraobservatory (dot) com, and tell him I said hey.

[Image: Victor Gruen gestures at a mall of his making; photo originally via The Fox is Black].

[Image: Victor Gruen gestures at a mall of his making; photo originally via The Fox is Black].

This is technically irrelevant, meanwhile, but it is nonetheless worth remembering that science fiction author Ray Bradbury—whose house of half a century was torn down by, of all people, architect Thom Mayne of Morphosis— claimed to have invented the indoor shopping mall.

Indeed, Bradbury recommended “giant malls as the cure to American urban decay,” Steve Rose explains in The Guardian. “‘Malls are substitute cities,’ [Bradbury] said at the time, ‘substitutes for the possible imagination of mayors, city councilmen and other people who don’t know what a city is while living right in the center of one. So it is up to corporations, creative corporations, to recreate the city.'”

In an essay posthumously published by The Paris Review, Bradbury anecdotally recounted a conversation he once had with architect Jon Jerde. Jerde asked Bradbury if he had ever visited a mall called the Glendale Galleria:

I said, “Yes, I have.”

“Did you like it?” he asked. I said, “Yes.”

He said, “That’s your Galleria. It’s based on the plans that you put in your article in the essay in the Los Angeles Times.” I was stunned. I said, “Are you telling me the truth? I created the Glendale Galleria?”

“Yes, you did,” he said. “Thank you for that article that you wrote about rebuilding L.A. We based our building of the Glendale Galleria completely on what you wrote in that article.”

What Bradbury wrote in that article was the idea that the vast interiors of future shopping malls would supply ersatz urban landscapes “where people could spend an afternoon, getting safely lost, just wandering about.”

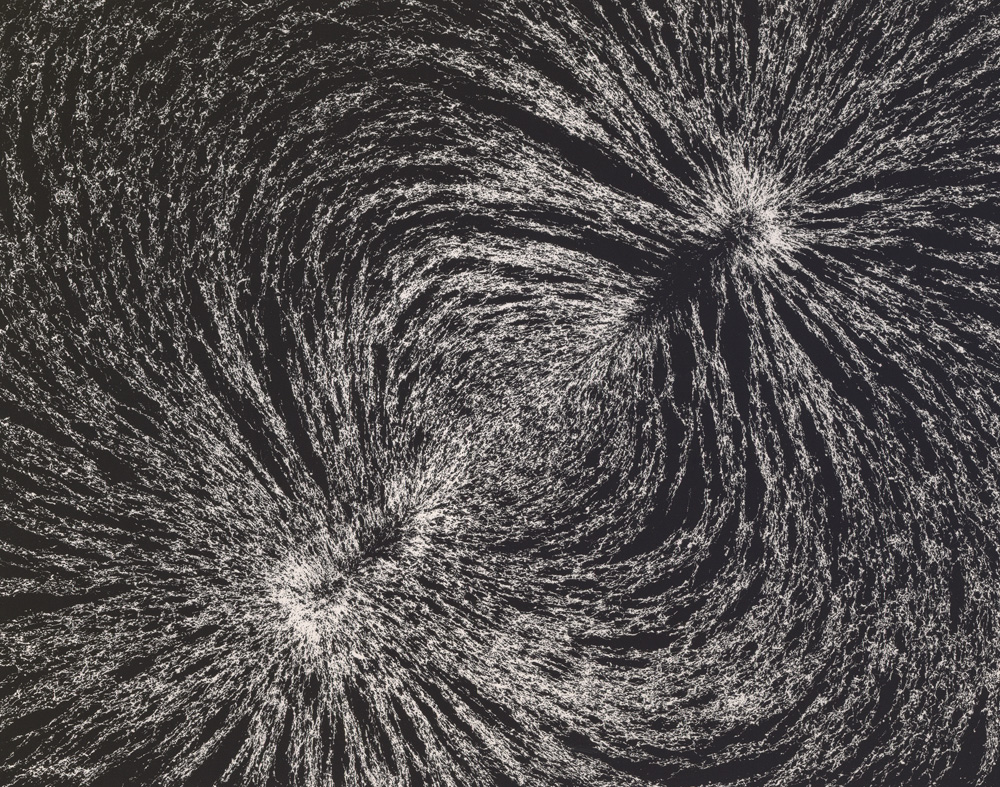

[Image: Guy Debord maps psychogeographic routes through Paris; perhaps, all along, psychogeography was just a confused first-person experience of the Gruen transfer on an urban scale].

[Image: Guy Debord maps psychogeographic routes through Paris; perhaps, all along, psychogeography was just a confused first-person experience of the Gruen transfer on an urban scale].

It was a psychogeography of the interior, as weary shoppers tracked whatever down-market dérive they could find amidst the mirrored escalators and mannequins.

Who knows if Ray Bradbury will come up during Gruen Day 2015, but be sure report back if you take the tour; be sure to email Tim Hwang if you’d like a free ticket.

[Image: Here’s another image from the same

[Image: Here’s another image from the same

[Image: Sewn geology; photo by Matthew Cox of

[Image: Sewn geology; photo by Matthew Cox of  [Image: Lifting up fake rocks; photo by Matthew Cox of

[Image: Lifting up fake rocks; photo by Matthew Cox of

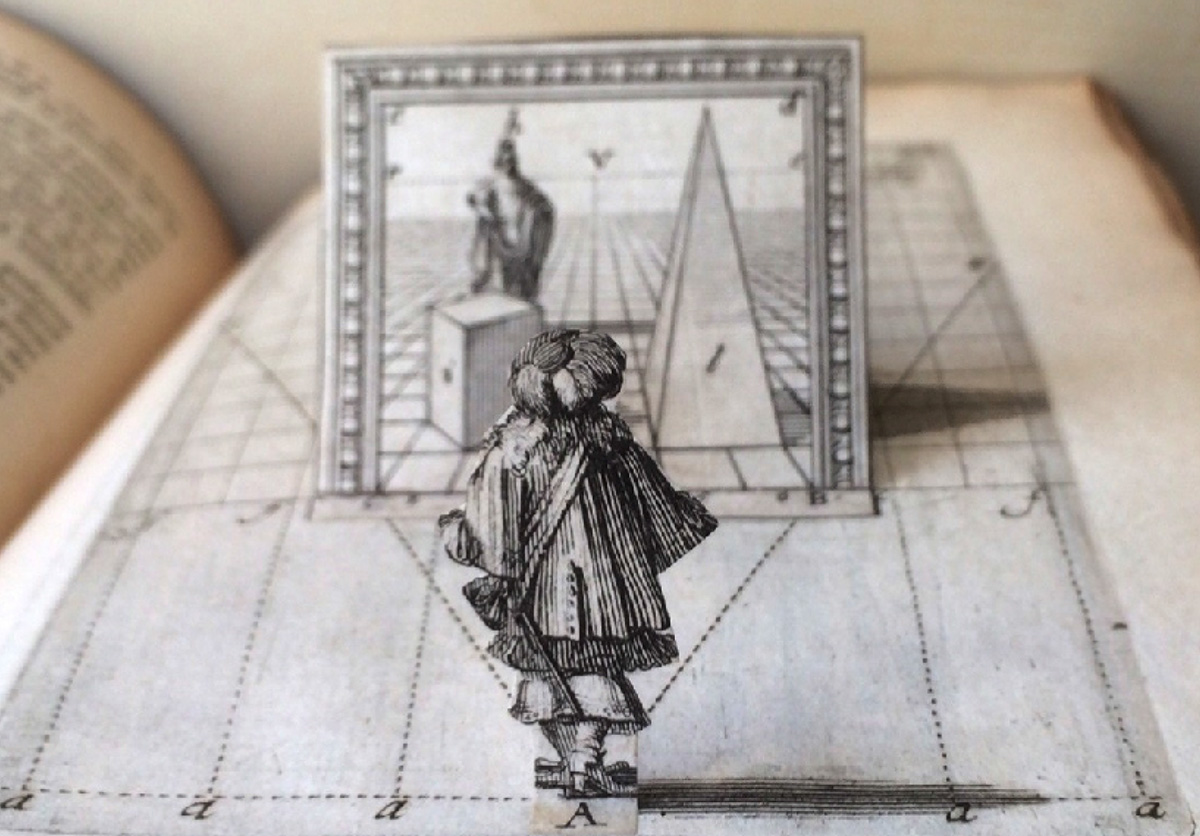

[Image: A figure and his optical context pop up from the pages of a 17th-century treatise on perspective by Abraham Bosse, defending the

[Image: A figure and his optical context pop up from the pages of a 17th-century treatise on perspective by Abraham Bosse, defending the

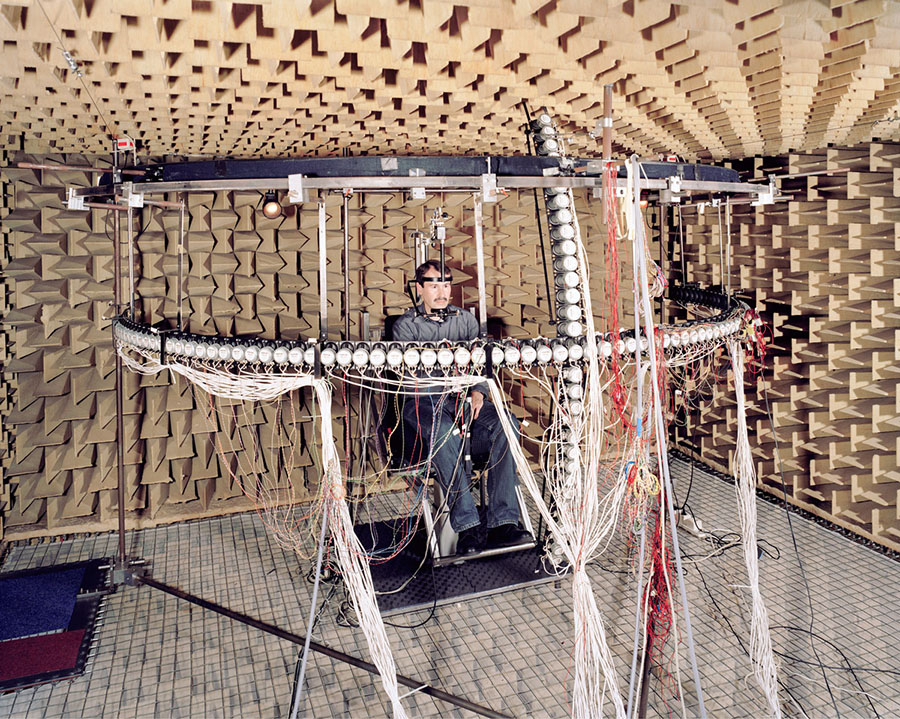

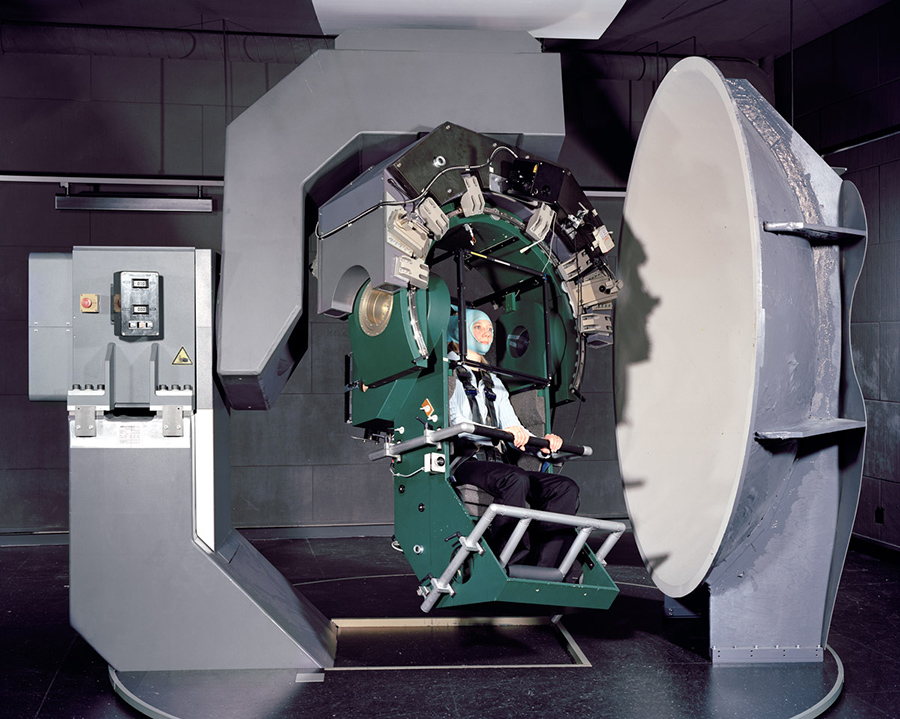

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Image:

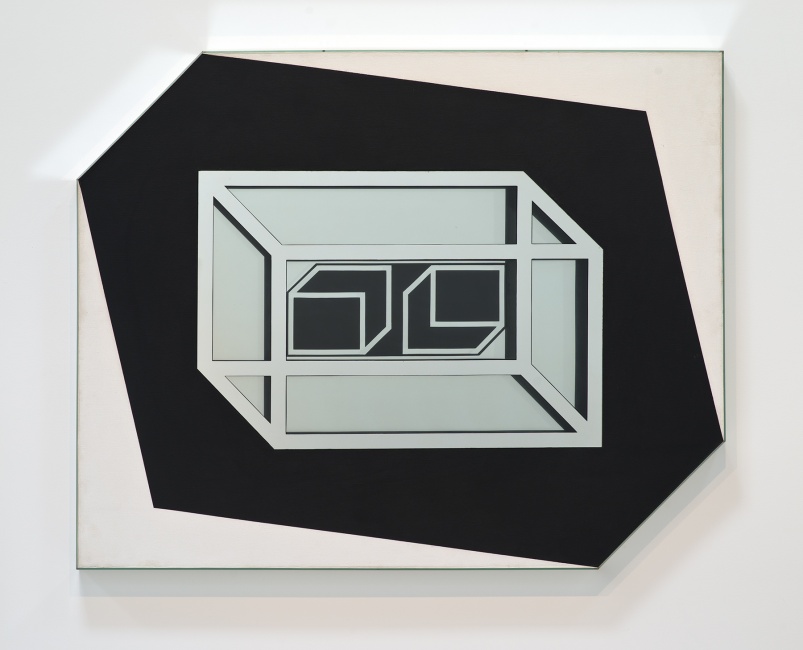

[Image:  [Image: “Untitled” by Larry Bell (1962), via the

[Image: “Untitled” by Larry Bell (1962), via the

[Image: A sidewalk corner in Los Angeles, albeit not the one for sale; via Google Street View].

[Image: A sidewalk corner in Los Angeles, albeit not the one for sale; via Google Street View].

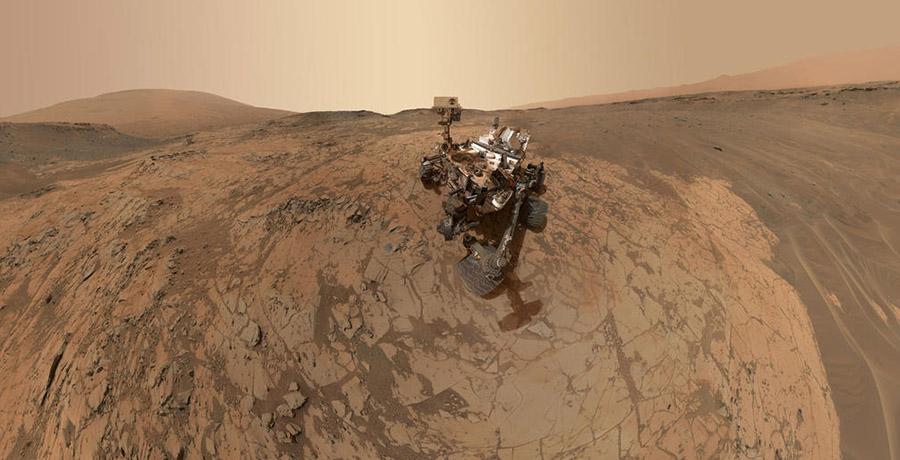

[Image: Self-portrait on Mars; via

[Image: Self-portrait on Mars; via  [Image: Another self-portrait on Mars; via

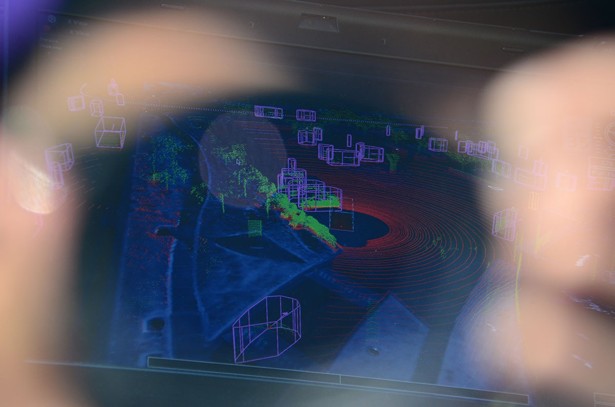

[Image: Another self-portrait on Mars; via  [Image: A glimpse of the dreaming; photo by

[Image: A glimpse of the dreaming; photo by

[Image: Navigating dreams within dreams: (top) from

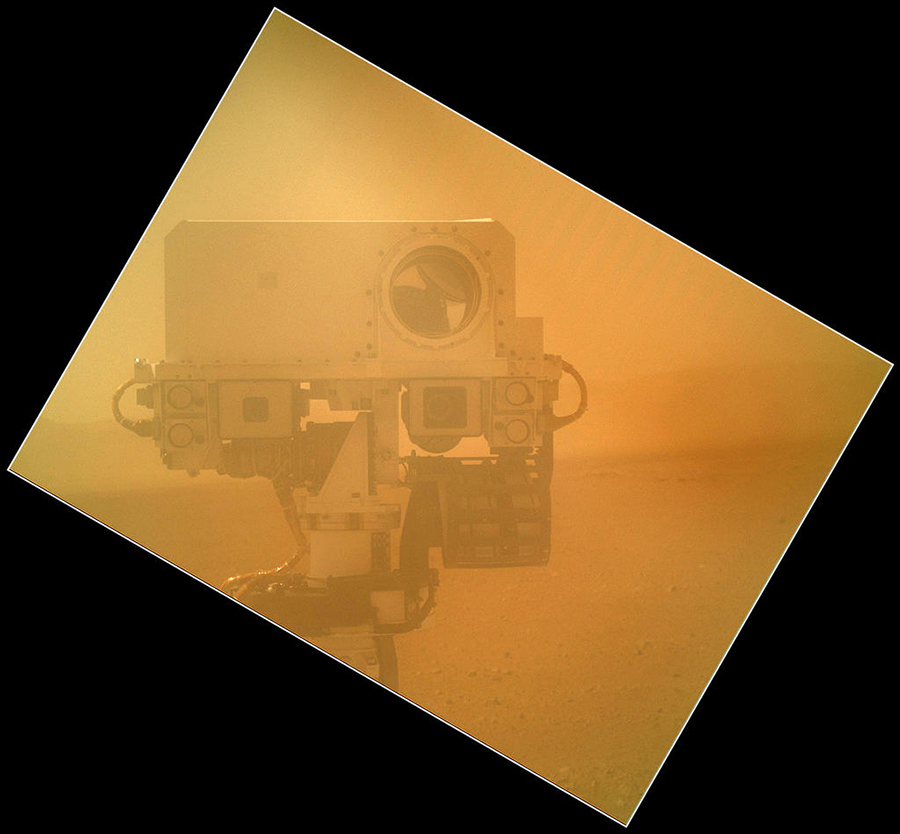

[Image: Navigating dreams within dreams: (top) from  [Image: Volitional portraiture on Mars; via

[Image: Volitional portraiture on Mars; via

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: One of many malls by Victor Gruen].

[Image: One of many malls by Victor Gruen]. [Image: Victor Gruen gestures at a mall of his making; photo originally via

[Image: Victor Gruen gestures at a mall of his making; photo originally via  [Image: Guy Debord maps psychogeographic routes through Paris; perhaps, all along, psychogeography was just a confused first-person experience of the Gruen transfer on an urban scale].

[Image: Guy Debord maps psychogeographic routes through Paris; perhaps, all along, psychogeography was just a confused first-person experience of the Gruen transfer on an urban scale].

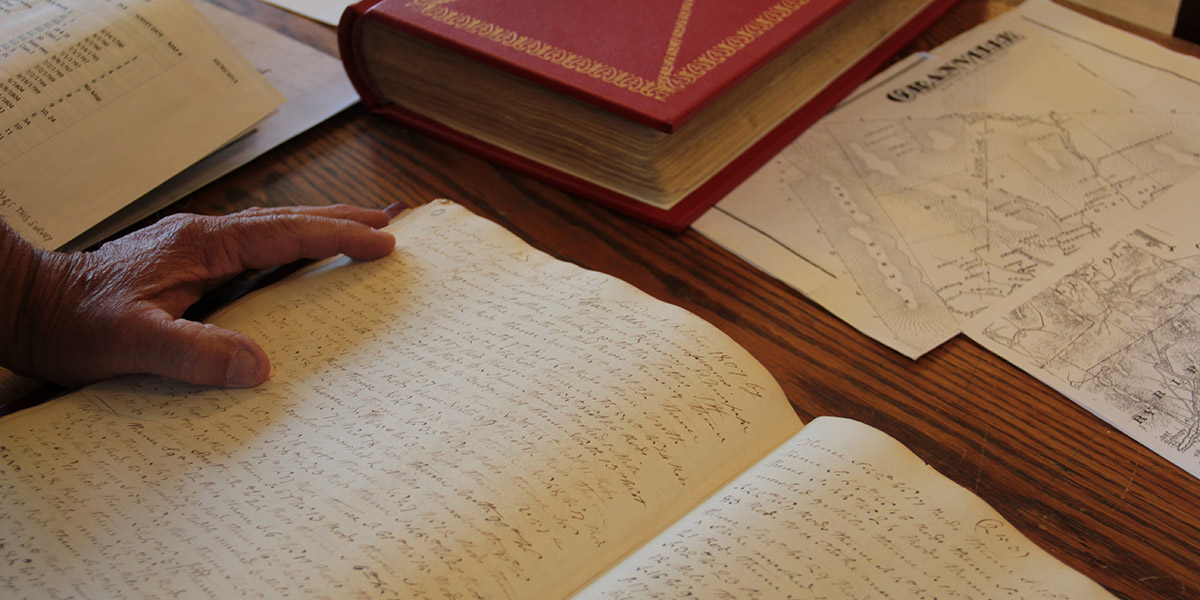

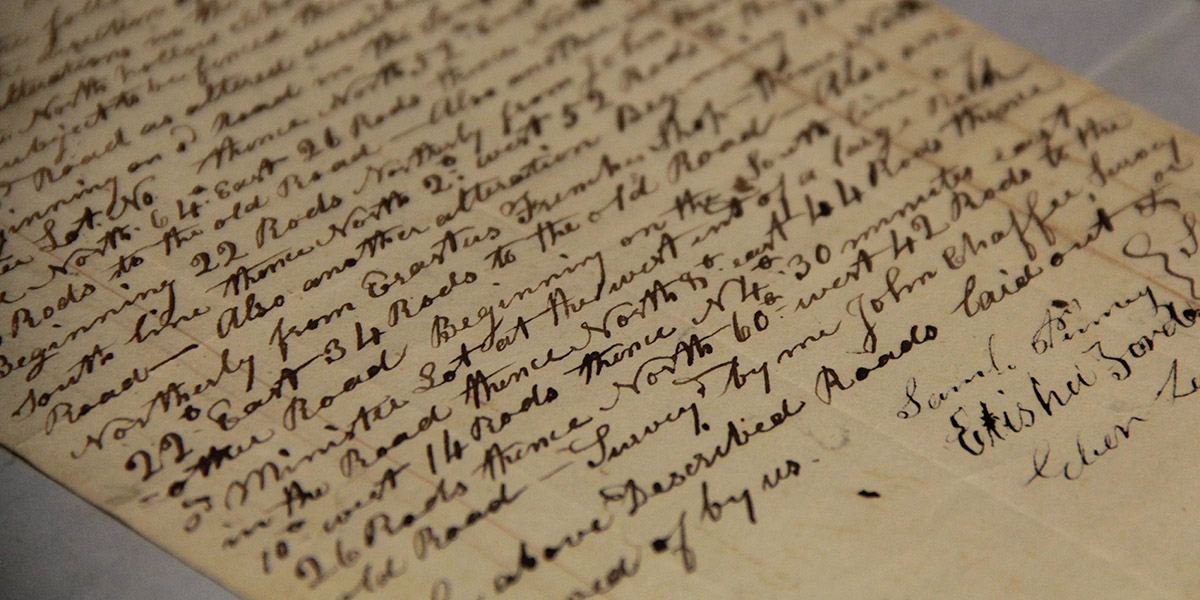

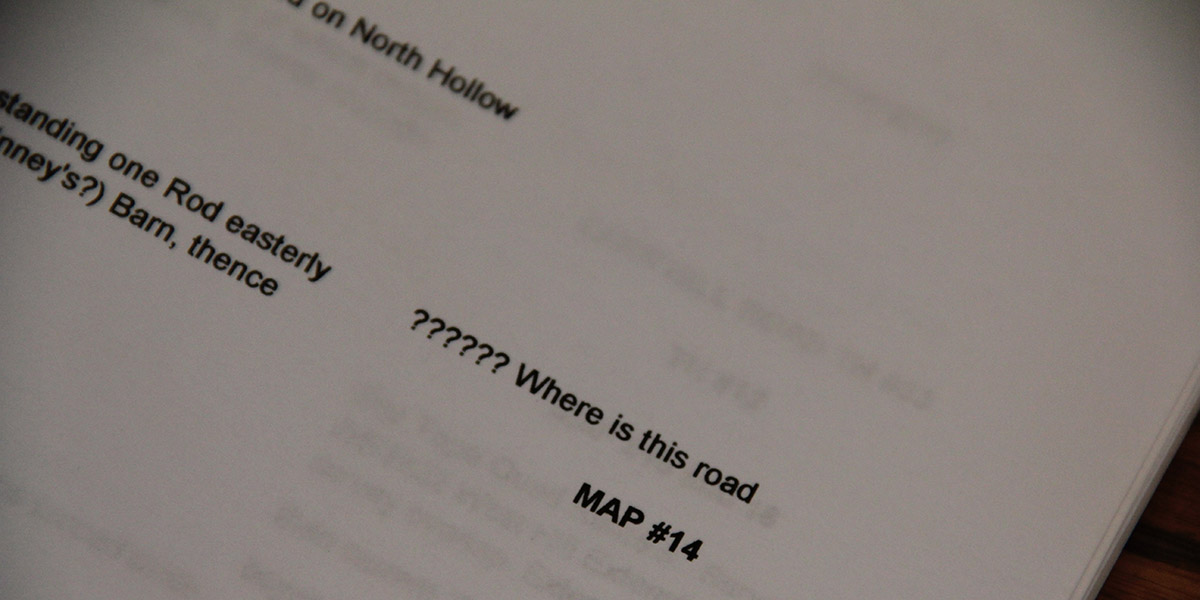

[Image: Reviewing old property deeds and land surveys; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

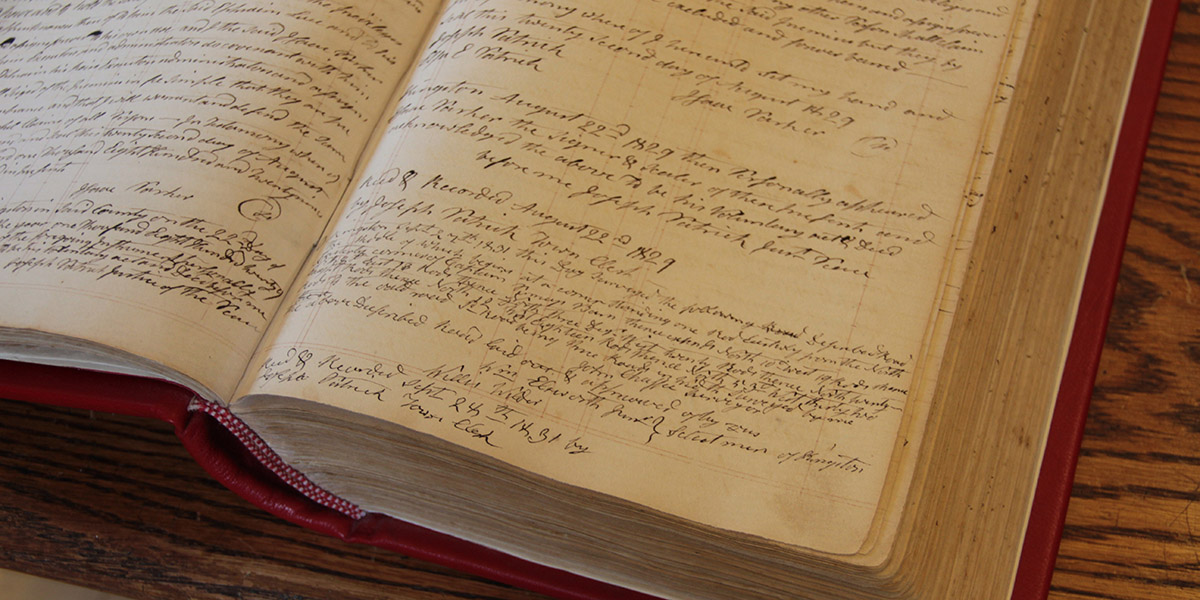

[Image: Reviewing old property deeds and land surveys; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: More Granville property deeds; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

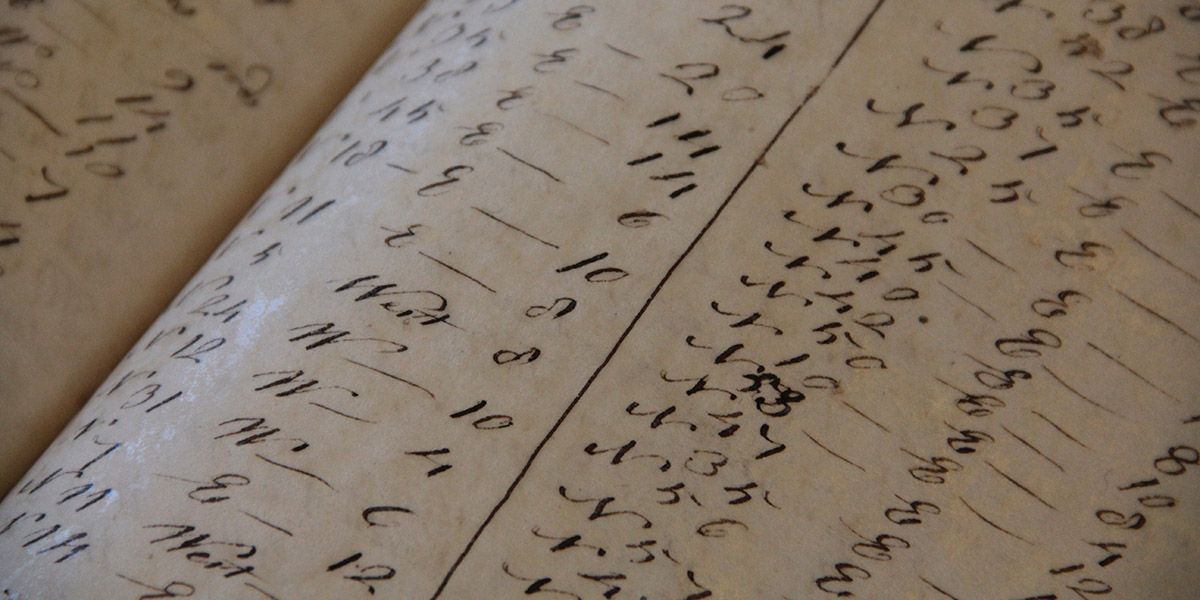

[Image: More Granville property deeds; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Geographic coordinates for lost roadways; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

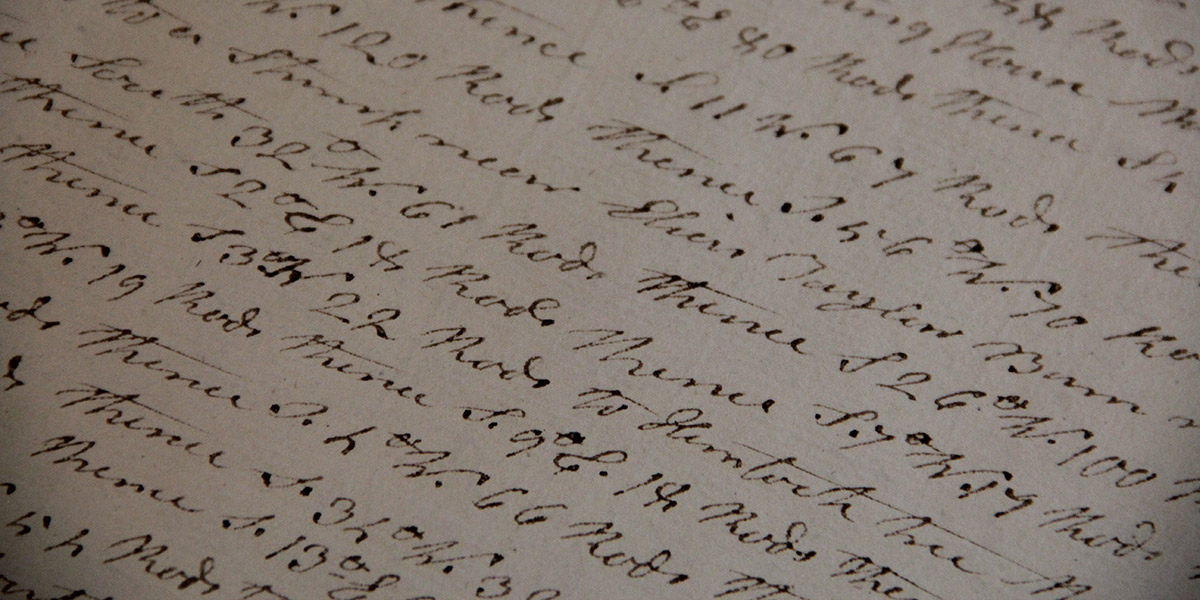

[Image: Geographic coordinates for lost roadways; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Zooming into survey descriptions of rods and chains; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Zooming into survey descriptions of rods and chains; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: Ancient road descriptions; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: Ancient road descriptions; photo by Geoff Manaugh]. [Image: “?????? Where is this road”; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

[Image: “?????? Where is this road”; photo by Geoff Manaugh].

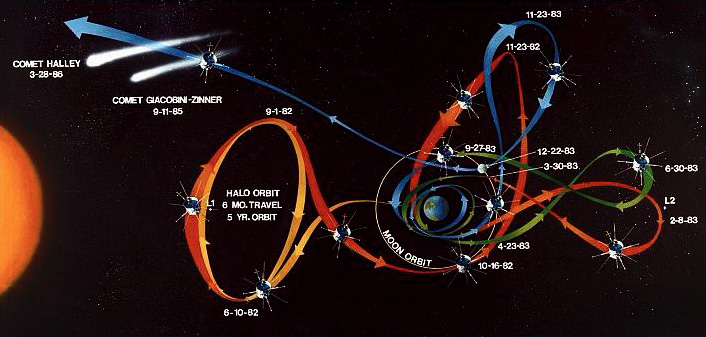

[Image: A diagram of the elaborate loops and ribbons of self-intersecting movement allowed by gravity-assisted travel, in this case heading toward a comet; original artist unknown].

[Image: A diagram of the elaborate loops and ribbons of self-intersecting movement allowed by gravity-assisted travel, in this case heading toward a comet; original artist unknown]. [Image: GIF by David Shortt, via

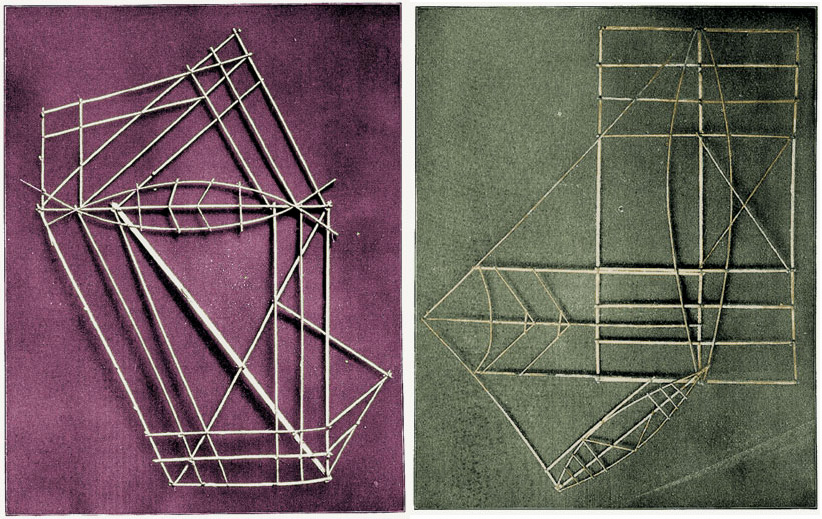

[Image: GIF by David Shortt, via  [Images: Polynesian “stick charts,” via

[Images: Polynesian “stick charts,” via  [Images: Polynesian “stick charts,” via

[Images: Polynesian “stick charts,” via