[Image: “Landscapes of Quarantine” meets at Storefront for Art and Architecture, October 2009].

[Image: “Landscapes of Quarantine” meets at Storefront for Art and Architecture, October 2009].

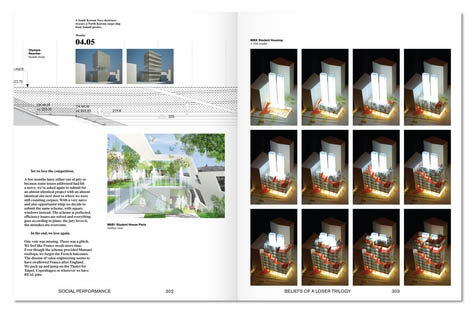

As many readers will already know, for the past two months BLDGBLOG has been teaming up with Edible Geography to lead an independent design studio called “Landscapes of Quarantine” in New York City. We’ve been meeting every Tuesday—and the odd Saturday—since October, using various spaces around Manhattan but, for the most part, based at Storefront for Art and Architecture (we’ve also met at Front Studio/Harvest and at Studio-X).

It’s all coming to an end this week, however, after which we’ll start getting ready for the “Landscapes of Quarantine” exhibition, which opens in March 2010 at Storefront for Art and Architecture. I thought, therefore, following Edible Geography‘s lead, that I should post some photographs from the previous eight weeks. These are less project documentation shots, however, than they are simply social photographs of our weekly meetings; for the projects themselves, expect more images coming up in the spring.

[Image: “Landscapes of Quarantine” meets at Storefront for Art and Architecture, December 2009].

[Image: “Landscapes of Quarantine” meets at Storefront for Art and Architecture, December 2009].

Of course, I realize that these photos will not be of immediate interest to everyone—but what I nonetheless like about them, and why they are appearing here, is that they show how a design studio without any official institutional affiliation can manage to set itself up, using equipment as simple as cheap wine, PDFs, and Post-It notes, inside already existing spaces around the city.

[Images: Scenes and friendly faces, including guest speaker Jake Barton, from “Landscapes of Quarantine,” autumn 2009].

[Images: Scenes and friendly faces, including guest speaker Jake Barton, from “Landscapes of Quarantine,” autumn 2009].

You don’t need a campus, in other words, or even a dedicated building (or room); you need a schedule, some colored markers, a stack of plastic cups, maybe a Google Groups account, and a willingness to participate in a structured conversation.

[Images: After hours on a Tuesday night at Storefront for Art and Architecture, autumn 2009].

[Images: After hours on a Tuesday night at Storefront for Art and Architecture, autumn 2009].

In fact, Nicola Twilley of Edible Geography and I have been joking that we wanted to start a kind of counterfeit university—that is, a form of continuing education that models itself on, and masquerades as, the very academic studio system it is meant to supplement (but not replace).

Whether or not any of that is told by the following photographs—let alone whether or not Nicola and I were actually successful—is something else altogether. But I’ll put these photos up here simply as an act of willful nostalgia and archival documentation. It’s been a great eight weeks. I regret no part of it—even living in a surreal, semi-abandoned building in New York City without a lease while everything we own remains boxed up in a storage unit in west Los Angeles.

[Images: Paola Antonelli from the Museum of Modern Art addresses the “Landscapes of Quarantine” group at Storefront for Art and Architecture, November 2009].

[Images: Paola Antonelli from the Museum of Modern Art addresses the “Landscapes of Quarantine” group at Storefront for Art and Architecture, November 2009].

The group has had some fantastic guest critics & speakers, as well. Architect Bjarke Ingels came by in October to see some initial project proposals; Paola Antonelli, senior curator of architecture and design at the Museum of Modern Art, gave us all an inspiring introduction to her own past work (and offered exhibition advice for the future); designer Jake Barton blew everyone away with some of the most interesting exhibition-design ideas out there today; architect and educator Laura Kurgan supplied much-needed feedback on our designs and conceptual approach; graphic designer Glen Cummings came by with countless examples of his books, pamphlets, posters, shows, and websites; and Joseph Grima, director of Storefront for Art and Architecture, gave us an eye-opening history of the space we all then sat in. We even got to meet the immensely talented (and intimidatingly young) landscape architects from paisajes emergentes, in town from Medellín, who stopped by one night to say hello.

[Images: Guest speakers Laura Kurgan and Glen Cummings address “Landscapes of Quarantine,” November 2009].

[Images: Guest speakers Laura Kurgan and Glen Cummings address “Landscapes of Quarantine,” November 2009].

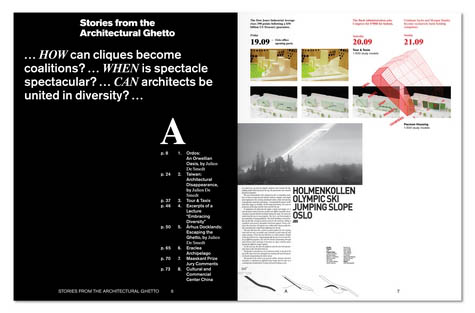

That’s in addition to the amazing group of people we had along for the ride. The breadth of our participants’ projects is extraordinary, and it’s worth taking a long look at how far they’ve been pushing the idea of quarantine. I’ll here paraphrase—or outright quote from—Edible Geography‘s own round-up of the studio.

At its most basic, quarantine is the creation of a hygienic boundary between two or more things, meant to protect one from exposure to the other. It is a spatial strategy of separation and containment, often invoked in response to suspicion, threat, and uncertainty.

Typically, quarantine is thought of in the context of disease control, where it used, somewhat mundanely, to isolate people who have been exposed to a contagious virus or bacteria (and who, as a result, might be carrying the infection themselves). According to historian David Barnes, quarantine was simply “an unpleasant fact of life” in most port cities for the duration of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (and, in some cases, earlier: in 1377, Dubrovnik became the first city-state to hold ships for a thirty day quarantine, on an island outside its harbor).

By the twentieth-century, this kind of routine application of quarantine was becoming less and less common. According to the Centers for Disease Control’s own “History of Quarantine“:

In the 1970s, infectious diseases were thought to be a thing of the past. At that time, CDC reduced the number of quarantine stations from 55 to 8. However, two major events—the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center in 2001 and the SARS outbreak in 2003—caused concerns about bioterrorism and the worldwide spread of disease. As a result, during 2004–2007, CDC increased the number of U.S. Quarantine Stations from 8 to 20.

This year’s swine flu pandemic has prompted an even greater awareness and enforcement of quarantine—although opinions are divided as to whether or not it has actually been effective in slowing the spread of disease.

[Images: Guest critic Bjarke Ingels surveys the scene as the “Landscapes of Quarantine” group presents their preliminary design ideas at Studio-X, October 2009].

[Images: Guest critic Bjarke Ingels surveys the scene as the “Landscapes of Quarantine” group presents their preliminary design ideas at Studio-X, October 2009].

The use of quarantine to restrict individual liberties in the name of public health raises a host of legal and ethical questions that proved a fruitful ground for discussions this autumn about the “dark math” of triage and “acceptable losses.”

Game designer Kevin Slavin, for instance, and comic book artist Joe Alterio are both now producing projects that investigate the challenge of shared responsibility and individual decision-making in the face of a deadly disease.

[Images: Add Post-It notes, and every wall becomes a university… Post-It notes at Storefront for Art and Architecture, autumn 2009].

[Images: Add Post-It notes, and every wall becomes a university… Post-It notes at Storefront for Art and Architecture, autumn 2009].

Other studio participants have identified an undercurrent of absurdity inherent to the practice of quarantine, and they have been gravitating toward almost Dada-like real-life images of tourists forcibly confined inside Chinese hotel rooms, receiving takeout food from biohazard-suited attendants, and the returning astronauts of the Apollo program who were denied their public ticker-tape parade and simply waved at by President Nixon through the window of a modified airstream trailer (which was itself later found, mysteriously, on a fish farm in Alabama).

Set designer Mimi Lien and graphic designer Amanda Spielman (in collaboration with her brother, Jordan) are both creating projects that play on the most surreal aspects of quarantined space, with (respectively) evocative, depopulated dioramas of unexpected quarantine locations, and a tongue-in-cheek public health campaign filled with helpful tips. These touch on making the most of your time in quarantine, for example, as well as on relationship-maintenance for married couples divided by quarantine.

Of course, quarantine does not only apply to people and animals. Its boundaries can be set up anywhere and for as long as necessary, creating spatial separation between the clean and the dirty, the safe and the dangerous, the healthy and the sick, the foreign and the native—no matter how those terms might be currently applied. Many of our readings and discussions thus focused on the technical challenges involved in using design to prevent the forward contamination of Mars or the spread of plant pests in an era of global climate change.

Artists Jamie Kruse and Elizabeth Ellsworth of Smudge Studio are focusing their attention on what they term the “limit-case” of quarantine: plans for the one-million-year containment of nuclear waste in subterranean geological repositories around the world. Is there such a thing as infinite quarantine, Smudge has asked, and how might that be represented on a comprehensible human timescale?

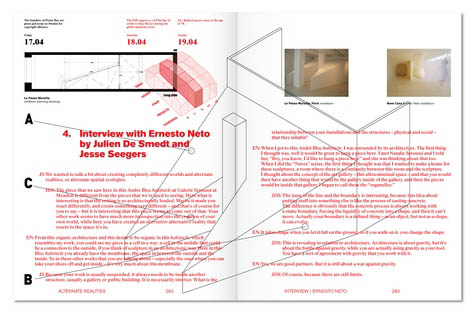

[Images: Smudge Studio‘s graphical analysis of how long-term nuclear waste repositories can be designed].

[Images: Smudge Studio‘s graphical analysis of how long-term nuclear waste repositories can be designed].

Of course, as a project of spatial control, the implications of quarantine ripple outward to affect the layouts of buildings, the shapes of cities, the borders of nations, and even the clothes we wear. Our weekly discussions have ranged from the fictional potential of quarantine (currently under investigation by writer Scott Geiger) to the infrastructural requirements of quarantine as it applies both to rare orchids and to the President of the United States (architect Thomas Pollman of the NYC Office of Emergency Management).

Architects Yen Ha and Michi Yanagishita of Front Studio are addressing the implications of inserting quarantine spaces directly into the fabric of the city, while architect Brian Slocum has been examining the way quarantine spaces blur the border between inside and outside, resident and visitor, homeland and foreign origin.

Some evenings, our conversations have revolved around the dystopian overlap between border controls and health screening, as well as what quarantine might look like from the point of view of the bacteria or virus that that quarantine has been set up to control (a twist that stems from architect and filmmaker Ed Keller‘s thoughts on networks, information virology, and what he calls political science fiction).

Scott Geiger, Kevin Slavin, and artist Katie Holten were brave enough to rise early on a cold October morning in order to catch the Staten Island ferry with us and witness the ceremonial re-interment of the quarantined dead during a bagpipe-accompanied church service. Later in the studio, Katie went back out onto the waters of the New York archipelago to visit North Brother Island, the final home of Typhoid Mary, where she stepped through ruined buildings half-buried in autumn leaves, while photographer Richard Mosse—previously interviewed here on BLDGBLOG—flew all the way to Malaysia as part of his fascinating exploration of vampirology, family history, and remote villages destroyed by the Nipah virus.

[Images: Benjamen Walker of WNYC records the final Tuesday evening of “Landscapes of Quarantine,” December 2009].

[Images: Benjamen Walker of WNYC records the final Tuesday evening of “Landscapes of Quarantine,” December 2009].

As some people might have noticed, on the other hand, we lost Lebbeus Woods (one of our studio’s original participants who, unfortunately, had to drop out of the proceedings), and we’ve been meeting with Jeffrey Inaba off-site in order to discuss his work (with C-LAB) for the exhibition.

You can read more about the studio here or here—and I want very much to point out to other people elsewhere that you don’t need to be connected to academia in order to put together a group of interesting and committed people for the purpose of pursuing an organized research project. You could work at Jamba Juice and still assemble a makeshift university. In fact, I’ve always thought it worth remembering that Thomas Bulfinch wrote his classic text Bulfinch’s Mythology while working day shifts as a bank teller in Boston.

But you need nothing more than a structure, a common topic, a place to meet up, a backpack full of the most basic office supplies, perhaps a bottle opener, and the will-power to see it through; with any luck, in other words, more “counterfeit universities” will be popping up here and there, their research published independently on blogs, their meetings hosted in apartments, offices, restaurants, bars, and other spaces in their after-hours, bringing more and more people into productive conversation.

This is how to make a “seed grenade,” “seed bomb,” or, more prosaically, seed ball.

This is how to make a “seed grenade,” “seed bomb,” or, more prosaically, seed ball. [Image: “This is what happens just a few day’s after dropping a seedbomb. The rain melted the clay and the compost, feeding the soil surrounding the bomb allowing for other plant growth.” Image and text from Guerilla Gardener’s Blog].

[Image: “This is what happens just a few day’s after dropping a seedbomb. The rain melted the clay and the compost, feeding the soil surrounding the bomb allowing for other plant growth.” Image and text from Guerilla Gardener’s Blog]. [Image: The DoChoDo Zoological Island by

[Image: The DoChoDo Zoological Island by

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: “Landscapes of Quarantine” meets at

[Image: “Landscapes of Quarantine” meets at  [Image: “Landscapes of Quarantine” meets at

[Image: “Landscapes of Quarantine” meets at

[Images: Scenes and friendly faces, including guest speaker

[Images: Scenes and friendly faces, including guest speaker  [Images: After hours on a Tuesday night at

[Images: After hours on a Tuesday night at

[Images: Paola Antonelli from the

[Images: Paola Antonelli from the

[Images: Guest speakers

[Images: Guest speakers

[Images: Guest critic

[Images: Guest critic

[Images: Add Post-It notes, and every wall becomes a university… Post-It notes at

[Images: Add Post-It notes, and every wall becomes a university… Post-It notes at

[Images:

[Images:  [Images:

[Images:  If I was in Los Angeles next week, I would definitely be aboard the Center for Land Use Interpretation’s forthcoming tour,

If I was in Los Angeles next week, I would definitely be aboard the Center for Land Use Interpretation’s forthcoming tour,  Being a long-time fan of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, meanwhile, I was excited to put together an infrastructure-based guide to the city of Los Angeles last year in the form of a short interview with CLUI director Matthew Coolidge. From human-waste-processing sites in El Segundo to the cell-phone towers atop Mt. Wilson—by way of gravel pits and methane-capture valves atop landfills—that tour can be found at

Being a long-time fan of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, meanwhile, I was excited to put together an infrastructure-based guide to the city of Los Angeles last year in the form of a short interview with CLUI director Matthew Coolidge. From human-waste-processing sites in El Segundo to the cell-phone towers atop Mt. Wilson—by way of gravel pits and methane-capture valves atop landfills—that tour can be found at  [Image: The Dariel Pass in the Caucausus Mountains, rumored possible site of the mythic

[Image: The Dariel Pass in the Caucausus Mountains, rumored possible site of the mythic  [Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, mythic isotope to Alexander’s Gates].

[Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, mythic isotope to Alexander’s Gates]. [Image: The geography of Us vs. Them, in a “12th century map by the Muslim scholar Al-Idrisi. ‘Yajooj’ and ‘Majooj’ (Gog and Magog) appear in Arabic script on the bottom-left edge of the Eurasian landmass, enclosed within dark mountains, at a location corresponding roughly to Mongolia.” Via

[Image: The geography of Us vs. Them, in a “12th century map by the Muslim scholar Al-Idrisi. ‘Yajooj’ and ‘Majooj’ (Gog and Magog) appear in Arabic script on the bottom-left edge of the Eurasian landmass, enclosed within dark mountains, at a location corresponding roughly to Mongolia.” Via  [Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, via

[Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, via  [Image: A map of the

[Image: A map of the  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Ad hoc infrastructure: “A convoy of sewage trucks removing solid waste from the city center. The current sewer system cannot handle the demand.” Photo by

[Image: Ad hoc infrastructure: “A convoy of sewage trucks removing solid waste from the city center. The current sewer system cannot handle the demand.” Photo by

[Images: (top) “A

[Images: (top) “A  [Image: Christmas trees for sale outside

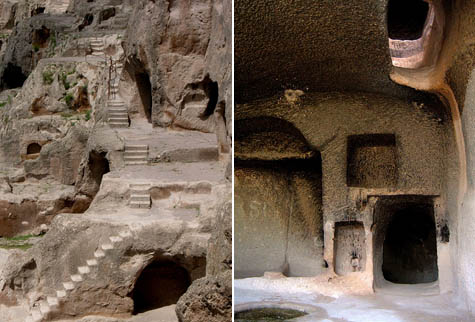

[Image: Christmas trees for sale outside  [Image: The Georgian cave monastery of Vardzia, via

[Image: The Georgian cave monastery of Vardzia, via  [Image: Vardzia, via

[Image: Vardzia, via  [Images: Vardzia, via

[Images: Vardzia, via  [Images: Vardzia, via

[Images: Vardzia, via

[Images: Vardzia, as seen in some

[Images: Vardzia, as seen in some  [Images: Vardzia, via

[Images: Vardzia, via  [Image: “Bunk beds are seen in a room in a black jail in Beijing in August 2009,” the

[Image: “Bunk beds are seen in a room in a black jail in Beijing in August 2009,” the  [Image: The Great Wall of China, via

[Image: The Great Wall of China, via  [Image: A scene of citizenry and its government, from

[Image: A scene of citizenry and its government, from  [Image: Stackin’ it at the

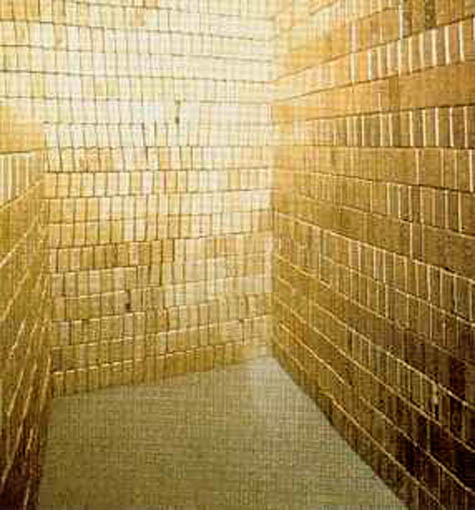

[Image: Stackin’ it at the  [Image: The solid gold walls of the U.S. Bullion Depository at

[Image: The solid gold walls of the U.S. Bullion Depository at