[Image: Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer by Caspar David Friedrich (c. 1818).]

[Image: Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer by Caspar David Friedrich (c. 1818).]

It would be interesting to look at locations of the American popular imagination, as seen in movies and TV, mapped against regional tax breaks for the film industry.

There was a brief span of time, for example, when rural Pennsylvania stood in for authentic Americana, a kind of Rust Belt imaginary, all pick-up trucks and hard-drinking younger brothers, stories framed against the hulking ruins of industrial landscapes—I’m thinking of Out Of The Furnace or Prisoners, both released in 2013, or even 2010’s Unstoppable. Whereas, today, Georgia seems to have stepped into that niche, between The Outsider and, say, Mindhunter (season two), let alone Atlanta, no doubt precisely because Georgia has well-known tax incentives in place for filming.

My point is that an entire generation of people—not just Americans, but film viewers and coronavirus quarantine streamers and TV binge-watchers around the world—might have their imaginative landscapes shaped not by immaterial forces, by symbolic archetypes or universal rules bubbling up from the high-pressure depths of human psychology, but instead by tax breaks offered in particular U.S. states at particular moments in American history.

You grow up thinking about Gothic pine forests, or you fall asleep at night with visions of rain-soaked Georgia parking lots crowding your head, but it’s not just because of the aesthetic or atmospheric appeal of those landscapes; it’s because those landscapes are, in effect, receiving imaginative subsidies from local business bureaus. You’re dreaming of them for a reason.

Your mind is not immaterial, in other words, some angelic force waltzing across the surface of the world, stopping now and again to dwell on universal imagery, but something deeply mundane, something sculpted by ridiculous things, like whether or not camera crews in a given state get hotel room discounts for productions lasting more than two weeks.

Of course, you could extend a similar kind of analysis way back into art history and look at, say, the opening of particular landscapes in western Europe, after decades of war, suddenly made safe for cultured travelers such as Caspar David Friedrich, whose paintings later came to define an entire era of European and European-descended male imaginations. That wanderer over a sea of fog, in other words, was wandering through a very specific landscape during a very particular window of European political accessibility. Had things been different, had history taken a slightly different path, Friedrich might have been stuck in his parents’ house, painting still-lives and weed-choked alleyways, and who knows what images today’s solo hikers might be daydreaming about instead.

[Image: From The Outsider, courtesy HBO; I should mention that The Outsider was set and filmed primarily in Georgia, a departure from Stephen King’s novel, which was primarily set in Oklahoma.]

[Image: From The Outsider, courtesy HBO; I should mention that The Outsider was set and filmed primarily in Georgia, a departure from Stephen King’s novel, which was primarily set in Oklahoma.]

In any case, the humid forests of rural America, the looming water towers and abandoned industrial facilities, the kudzu-covered strip malls and furloughed police stations—picture the Louisianan expanses of True Detective (season one)—have come to represent the dark narrative potential of the contemporary world. But what if, say, North Dakota or Manitoba (where, for example, The Grudge was recently filmed) had offered better tax breaks?

My own childhood imagination was a world of sunlit suburbs, detached single-family homes, and long-shadowed neighborhood secrets, but, as to my larger point here, I also grew up watching movies like E.T., Poltergeist, Fright Night, and Blue Velvet—so, in a sense, of course I would think that’s what the world looked like.

[Image: From David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), specifically via the site Velvet Eyes.]

[Image: From David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), specifically via the site Velvet Eyes.]

So, again, it would be interesting to explore how one’s vision of the world—your most fundamental imagination of the cosmos—is being shaped for you by tax breaks, film incentives, and other, utterly trivial local concerns, like whether or not out-of-state catering companies can get refunds on expenditures over a certain amount or where actors can write off per diems as gifts, not income, affecting whether crime films or horror stories will be shot there, and thus where an entire generation’s future nightmares might be set.

Or, for that matter, you could look at when particular colors, paints, and pigments became affordable for artists of a certain era, resulting in all those dark and moody images you love to stare at in the local museum—e.g. the old joke that, at some point, Rembrandt simply bought too much purple. It wasn’t promethean inspiration; it was material surplus.

We see things for a reason, yet, over and over again, mistake our dreams for signs of the cosmic. Or, to put this another way, we are not surrounded by mythology; we are surrounded by economics. The latter is a superb and confusing mimic.

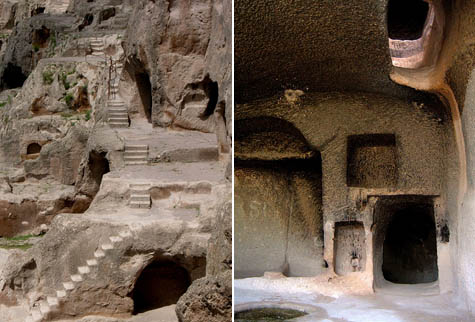

[Image: The Georgian cave monastery of Vardzia, via

[Image: The Georgian cave monastery of Vardzia, via  [Image: Vardzia, via

[Image: Vardzia, via  [Images: Vardzia, via

[Images: Vardzia, via  [Images: Vardzia, via

[Images: Vardzia, via

[Images: Vardzia, as seen in some

[Images: Vardzia, as seen in some  [Images: Vardzia, via

[Images: Vardzia, via