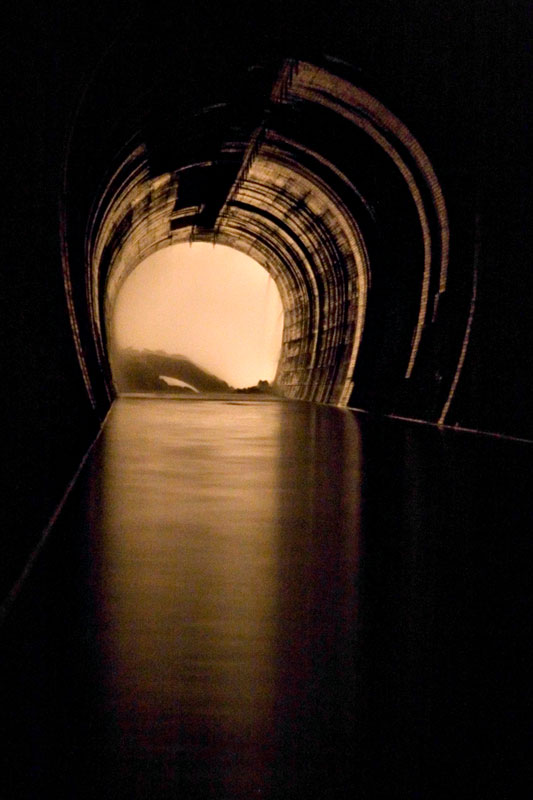

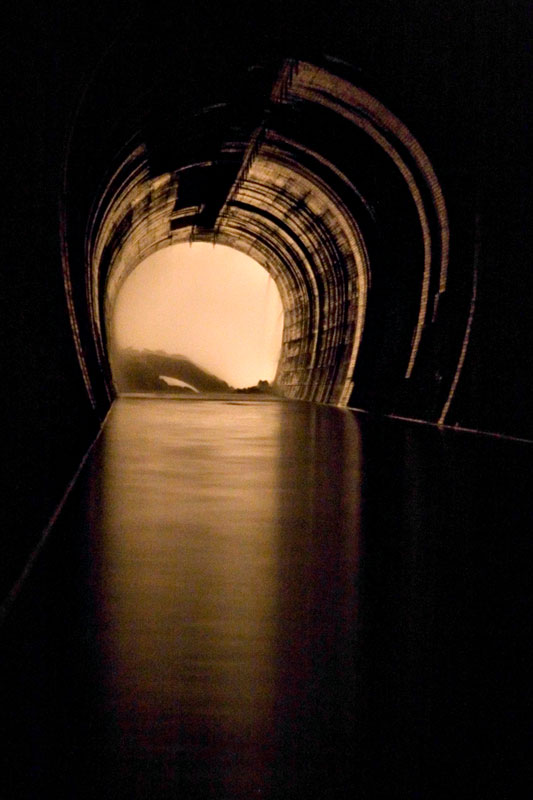

[Image: The Toronto Power Company Tailrace at Niagara; this and all other photos in this post by Michael Cook].

[Image: The Toronto Power Company Tailrace at Niagara; this and all other photos in this post by Michael Cook].

Michael Cook is a writer, photographer, and urban explorer based in Toronto, where he also runs a website called Vanishing Point.

Despite its subject matter, however, Vanishing Point is more than just another website about urban exploration. Cook’s accounts of his journeys into the subterranean civic infrastructure of Canada and northern New York State – and into those regions’ warehouses, factories, and crumbling hospitals – often include plans, elevations, and the odd historical photograph showing the sites under construction.

For instance, his fascinating, inside-out look at the Ontario Generating Station comes with far more than just cool pictures of an abandoned hydroelectric complex behind the water at Niagara Falls, and the detailed narratives he’s produced about the drains of Hamilton and Toronto are well worth reading in full.

As the present interview makes clear, Cook’s interests extend beyond the field of urban exploration to include the ecological consequences of city drainage systems, the literal nature of public space, and the implications of industrial decay for future archaeology – among many other things we barely had time to discuss.

Or, perhaps more accurately phrased, Cook shows that urban exploration has always been about more than just taking pictures of monumentally abstract architectural spaces embedded somewhere in the darkness.

[Image: The Memorial Park Storage Chambers in Toronto’s Belt Line Drain; this is architecture as dreamed of by Adolf Loos: shaved of all ornament, exquisitely smooth, functional – while architecture schools were busy teaching Mies van der Rohe, civil engineers were perfecting the Modern movement beneath their feet].

[Image: The Memorial Park Storage Chambers in Toronto’s Belt Line Drain; this is architecture as dreamed of by Adolf Loos: shaved of all ornament, exquisitely smooth, functional – while architecture schools were busy teaching Mies van der Rohe, civil engineers were perfecting the Modern movement beneath their feet].

As he writes on Vanishing Point:

The built environment of the city has always been incomplete, by omission and necessity, and will remain so. Despite the visions of futurists, the work of our planners and cement-layers thankfully remains a fractured and discontinuous whole, an urban field riven with internal margins, pockmarked by decay, underlaid with secret waterways. Stepping outside our prearranged traffic patterns and established destinations, we find a city laced with liminality, with borderlands cutting across its heart and reaching into its sky. We find a thousand vanishing points, each unique, each alive, each pregnant with riches and wonders and time.

This is a website about exploring some of those spaces, about immersing oneself in stormwater sewers and utility tunnels and abandoned industry, about tapping into the worlds that are embedded in our urban environment yet are decidedly removed from the collective experience of civilized life. This is a website about spaces that exist at the boundaries of modern control, as concessions to the landscape, as the debris left by economic transition, as evidence of the transient nature of our place upon this earth.

In the following conversation with BLDGBLOG, Cook discusses how and where these drains are found; what they sound like; the injuries and infections associated with such explorations; myths of secret systems in other cities; and even a few brief tips for getting inside these hyper-functionalist examples of urban infrastructure. We talk about ecology, hydrology, and industrial archaeology; and we come back more than once to the actual architecture of these spaces.

[Image: “Stairs” by Michael Cook, from the Westview Greenbelt Drain].

[Image: “Stairs” by Michael Cook, from the Westview Greenbelt Drain].

• • •BLDGBLOG: Is there any place in particular that you’re exploring right now?

Michael Cook: I am trying to piece together entrance to a drain here in Toronto. It’s part of a larger system. As part of their efforts to improve Toronto’s water quality on the lake front, the city built this big storage tunnel called the Western Beaches Storage Tunnel. It intercepts and stores overflow from a number of combined sewers, as well as from several storm sewers along the western lake front. I guess this was finished in 2001, but they had various technical issues, with the mechanics of it, so it was only operational this past summer.

But there are three storm sewers, I guess, that are part of this system. One of them is on my site already – Pilgrimage – and then there’s a second one that’s large and possibly worth getting into. It’s just not something I’ve investigated thoroughly, so… I’ll probably go down and look for that.

[Images: (top) “Transition to CMP,” from Toronto’s Old Ironsides drain; (middle) “Junction with small sidepipe (falling in on the right)” inside Toronto’s Graphic Equalizer drain; (bottom) “Backwards junction” in Toronto’s Sisters of Mercy drain].

[Images: (top) “Transition to CMP,” from Toronto’s Old Ironsides drain; (middle) “Junction with small sidepipe (falling in on the right)” inside Toronto’s Graphic Equalizer drain; (bottom) “Backwards junction” in Toronto’s Sisters of Mercy drain].

BLDGBLOG: How do you know that the system fits together – that all these storm sewers actually connect up with one another? Are there maps?

Michael Cook: In this case, I have an outfall list that was prepared in the late 80s for portions of Toronto – so I know, from this list, what the size of this storm sewer was at its outfall, before it was intercepted by the new system.

There was also a fair bit of media coverage when the system was being built, because it was a huge expenditure on the part of the city. So we know which combined sewers are part of the system, and I do know where a particular storm sewer is when they intersect – I just don’t necessarily know which residential streets it runs under.

Basically, I have a starting point – and the way I’m going to do this is just go down there on foot and walk around the various residential streets, starting at the lake and moving north. I’ll see if I can find any viable manhole entrances – which involves being by the side of the road or in the sidewalk, where it will be possible to enter and exit safely.

[Image: “Emerging in Wilson Heights,” out of Toronto’s Depths of Salvation drain].

[Image: “Emerging in Wilson Heights,” out of Toronto’s Depths of Salvation drain].

BLDGBLOG: What do you actually bring with you? Do you have some kind of underground exploration kit? Full of Band-Aids and Advil?

Michael Cook: I have a pair of boots or waders, depending on the circumstances. I’ll also bring one or more headlamps, and a spotlamp, and various other lighting gear – plus a camera and a tripod. That basically sums it up.

I also have a manhole key – that’s basically just a loop of aircraft cable tied onto a bolt at one end and run through a piece of aluminum pipe that serves as a crude handle. Most of the manhole lids around here have between two and twenty square holes in them about an inch wide, and they’re reasonably light. Assuming the lid hasn’t been welded or bolted into the collar of the manhole, it’s relatively quick and painless to use this tool to pull the lid out. It’s only useful for light-weight lids, though. In Montreal, for instance, most of the covers are awkward, heavy affairs that sometimes need two people, each with their own crowbar, to dislodge safely. Real utilities workers use pickaxes – but those aren’t so easily carried in the pocket of a backpack.

[Image: The outfall of Toronto’s Old Ironsides drain].

[Image: The outfall of Toronto’s Old Ironsides drain].

BLDGBLOG: Do you ever run into other people down there?

Michael Cook: That’s never happened to me, actually. It’s just not that popular a pursuit, outside of certain hotspots.

People can accept going into an abandoned building: you might run into someone you don’t want to run into there, or you might find that part of the building’s unstable – but it’s still just a building.

Even people I know who self-identify as urban explorers aren’t at all that interested in undergrounding – especially not in storm drains. A lot of them just don’t see the actual interest. It’s not a detail-rich environment. You can walk six kilometers underground through nearly featureless pipe – and there’s not something to see and photograph every five feet.

[Image: An “A-shaped conduit” in Toronto’s Belt Line Drain].

[Image: An “A-shaped conduit” in Toronto’s Belt Line Drain].

BLDGBLOG: Yet a lot – possibly most – of these drains are already named. Who names them, and how do the names get passed around and agreed on by everyone else?

Michael Cook: With people who drain, one of the first things you pick up is a respect for existing names – and the first person to explore a drain has naming rights over it. People generally respect that. Sometimes we’ll make exceptions – I know I’ve made exceptions a few times – but, ultimately, we depend on other people respecting our names.

It’s at once a completely pointless exercise; but, at the same time, it’s fairly meaningful in terms of having a way of discussing this with other people.

So that’s how it comes up. You then use that name, both offline and online. In Australia, they have a kind of master location list, that they keep within Cave Clan, but here we don’t have that level of organization, or that size of a community. It’s just a matter of publishing stuff on our websites.

That said, sometimes we’ll adopt the official name. This usually happens when we’ve been using that name for awhile before we find a way to actually get inside the system, and this usually comes about with something really big or historically significant. We’ll never rename the Western Beaches Storage Tunnel, for instance, though we call it the “Webster,” colloquially. When I find a way into Toronto’s storied Garrison Creek Sewer, the buried remains of our fabled “lost” creek, it won’t be the subject of renaming either. Those are the exceptions though; most of the time naming is one of the things we do to capture and communicate something of the magic of wading for three hours through a watery, feature-poor concrete tunnel underground.

[Image: (top) “Outfall structure in the West Don Valley,” part of Toronto’s Depths of Salvation drain; (bottom) The outfall of Toronto’s Graphic Equalizer drain].

[Image: (top) “Outfall structure in the West Don Valley,” part of Toronto’s Depths of Salvation drain; (bottom) The outfall of Toronto’s Graphic Equalizer drain].

BLDGBLOG: A lot of these places look like surreal, concrete versions of all the streams and rivers that used to flow through the city. The drains are like a manmade replacement, or prosthetic landscape, that’s been installed inside the old one. Does the relationship between these tunnels and the natural waterways that they’ve replaced interest you at all?

Michael Cook: Oh, definitely – ever since I got into this through exploring creeks.

At their root, most drains are just an abstract version of the watershed that existed before the city. It’s sort of this alternate dimension that you pass into, when you step from the aboveground creek, through the inlet, into the drain – especially once you walk out of the reach of daylight.

Even sanitary sewers often follow the paths of existing or former watersheds, because the grade of the land is already ideal for water flow – fast enough, but not so fast that it erodes the pipe prematurely – and because the floodplains are often unsuitable for other uses.

[Image: “Outfall in winter” at Toronto’s Gargantua drain].

[Image: “Outfall in winter” at Toronto’s Gargantua drain].

BLDGBLOG: How does that affect your attitude toward this, though? Do you find yourself wishing that all these drains could be dismantled, letting the natural landscape return – or, because these sites are so interesting to explore, do you actually wish that there were more of them?

Michael Cook: It’s an awful toll that we’ve taken on the landscape – I’m not one to celebrate all this concrete. If it were conceivable to set it all right, I’d be the first one in line to support that. And the marginal progress being made in terms of environmental engineering – building storm water management alternatives to burial and to large, expensive pipes – is a great step forward; unfortunately, its success so far has been limited.

Ultimately, you just can’t change the fact that we’ve urbanized, and we continue to do so. That comes with a cost that can be managed – but it can’t be eliminated completely.

[Image: Looking out of a spillway at the Ontario Generating Station].

[Image: Looking out of a spillway at the Ontario Generating Station].

BLDGBLOG: So do you actually have an environmental goal with these photographs? Your explorations are really a form of environmental advocacy?

Michael Cook: Well, I want to find something that goes a bit further than just presenting these photos for their aesthetic value – but, at the same time, turning this into some sort of environmental advocacy platform doesn’t really come to mind, either.

I’m very interested in urban ecology and in the environmental politics that take place in the city – and I’ve done some academic work in that regard – but I’m not really prepared to distill the photography and these adventures into an activist exercise.

[Image: The “spectacular, formerly natural waterfall that the [Chedoke Falls Drain] now feeds,” in Hamilton, Ontario].

[Image: The “spectacular, formerly natural waterfall that the [Chedoke Falls Drain] now feeds,” in Hamilton, Ontario].

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious if you’ve ever been injured, or even gotten sick, down there. All that old, stagnant air – and the dust, and the germs – can’t be very good for you!

Michael Cook: I can’t say that I’ve ever gotten sick from it. Sometimes, the day after, you can feel almost hung-over – but I don’t know what that is. It could be dust, or it could be from the amount of moisture you breathe in. But it passes. It may even be an allergy I have.

I haven’t really done any exploration of sanitary sewers – that would be a different story. In Minneapolis/St. Paul they actually have a name for the sickness they sometimes come down with after a particularly intense sewer exploration: Rinker’s Revenge. It’s named after the engineer who designed the systems there. And a colleague caught a bout of giardia recently, which he believes he acquired exploring a section of combined sewer in Montreal.

So, obviously, there are disease risks in doing this, though they’re not as extensive as one might want to imagine.

The only serious situation I’ve ever been in, with a high potential for injury – and I was pretty lucky – was while exploring in Niagara. The surge spillways for the Ontario Generating Station used to carry overflow water from the surge tanks, and those were fed by the intake pipes. So the water would overflow from the intake pipes into the surge tanks, and then drain out through these helical spillways that spiral downwards to the bottom of the gorge. They then outfall in front of the plant into the river.

So we made an attempt to ascend both of these spillways, and we were successful in the first one; but the second one, we found, was more difficult toward the latter stages of the climb. We had to turn back just before reaching the surge tanks. On the way back down I lost my footing – I lost all grip on the surface, it was so steep and so slippery, and it was covered in very fine grit – and I ended up sliding all the way down to the bottom, nearly 200 vertical feet. And I was going at a very high speed by the time I reached the bottom.

I was very lucky to come away from that with just a few friction burns and a sprained thumb.

[Images: A “short drop” in Toronto’s beautifully torqued and ovoid Viceroy Drain].

[Images: A “short drop” in Toronto’s beautifully torqued and ovoid Viceroy Drain].

BLDGBLOG: As far as the actual tunnels go, how connected is all this stuff? Is it like a big, underground labyrinth sometimes – or just a bunch of little tunnels that look connected only because of the way that they’ve been photographed?

Michael Cook: Well, most of the drainage systems I’ve been in are pretty linear. You have a main trunk conduit, and then sometimes you’ll get significant side pipes that are worth exploring. But as far as actual maze-quality features go, it’s pretty rare to find systems like that – at least in Ontario and most places in Canada. It requires a very specific geography and a sort of time line of development for the drains.

You might end up with a lot of side overflows and other things, which makes the system more complicated, if the drain has several different places where it overflows into a surface body of water – or if there’s a structure that allows one pipe to flow into another at excess capacity. That sort of thing allows for more complicated systems – but most of the time it doesn’t happen.

You can still spend hours in some of these drains, though, because of how long they are. And sometimes that makes for a fairly uninteresting experience: drains can be pretty featureless for most of their length.

[Images: Four glimpses of the vaulted topologies installed inside the Earth at Niagara’s William Birch Rankine Hydroelectric Tailrace].

[Images: Four glimpses of the vaulted topologies installed inside the Earth at Niagara’s William Birch Rankine Hydroelectric Tailrace].

BLDGBLOG: Are the drains up there mostly poured concrete, or are they made of brick?

Michael Cook: We have recently opened up our first significant brick sewer in Toronto – The Skin of a Lion – which is built from yellow brick and would probably date to around the turn of the last century. So there are a few locations where you can find brick, but most are concrete.

[Images: (top) Leaving the William Birch Rankine Hydroelectric Tailrace, Niagara Falls; (bottom) Tailrace outlet, William B. Rankine Generating Station].

[Images: (top) Leaving the William Birch Rankine Hydroelectric Tailrace, Niagara Falls; (bottom) Tailrace outlet, William B. Rankine Generating Station].

BLDGBLOG: Does that affect what the drains sound like, as far as echoes and reverb go? What sort of noises do you hear?

Michael Cook: I’d say that every drain is acoustically unique. Each has its own resonance points – and even different sections of the drain will resonate differently, based on where the next curve is, or the next room. It all shifts. I often explore that aspect a bit – probably to the annoyance of some of my colleagues. I’ll make noises, or hum. Even sing.

As far as environmental noises, the biggest thing is that, if there’s a rail line nearby, or a public transit line, you often get that noise coming back through the drain to wherever you are. It’s very frightening when you first hear it, till you figure out what it is – this rushing noise. It’s not a wall of water. [laughs]

But the most common recurring noise is the sound of cars driving over manhole covers – which gives you an idea of which covers you don’t want to exit through. It also helps you keep track of the distance, and where you are – that sort of thing.

[Image: “Transitions” inside the Duncan’s Got Wood sewer, Toronto].

[Image: “Transitions” inside the Duncan’s Got Wood sewer, Toronto].

BLDGBLOG: What kind of legal issues are involved here – like trespassing, or even loitering? Do you have to go out at 2am, dressed like an official city worker, or wear a hood or anything like that?

Michael Cook: For draining, the legal issues are pretty grey. After all, you’re on public property the entire time – so the risk of a serious trespassing fine is a lot lower. There’s no private security company looking out for you, and there’s no private property owner who’s going to be irate if you’re found inside his building. It’s a municipal waterway – it just happens to run underground. A lot of times the outfalls aren’t even posted with notices telling you to stay out.

Now, some people have been given fines for trespassing – for having been inside drains in Ontario – but these have been for pretty minor sums of money. It’s not something that I’ve ever had a problem with – and definitely not something that requires me to go in the middle of the night.

The only thing that really dictates what time you can go is traffic conditions. If you have to use a street-side manhole, you generally don’t want to be doing that doing the day.

[Image: “Deep inside the century-old wheelpit that is the beginning of the Rankine Generating Station Tailrace” (view bigger)].

[Image: “Deep inside the century-old wheelpit that is the beginning of the Rankine Generating Station Tailrace” (view bigger)].

BLDGBLOG: Within Toronto itself, are you still finding new drains, or is the city pretty much exhausted by now?

Michael Cook: We are still finding new tunnels beneath Toronto, and we’re on the trail of others that we know about but just haven’t discovered access to yet. There are also still a few underground gems in Hamilton that haven’t been seen by anyone except municipal workers and a handful of journalists. These days though, Montreal and Vancouver are emerging hotbeds for new sewer and drainage finds in Canada, thanks to explorers in those cities.

When Siologen came over here he found a whole bunch of new drain systems in Toronto – systems nobody else knew about. He had the time and the inclination to go and scout out a whole lot of stuff that I’d never gotten around to doing.

BLDGBLOG: How’d he do that?

Michael Cook: Basically by riding all the buses. That, and looking at a lot of little creek systems, and searching around for manholes – all of that.

But there are people who happen to read in the paper about some new tunnel project, or whatever, and so they pass that on to people who do this sort of thing. Outside of that, I don’t really know what to say. I guess some people have even found stuff after it’s been featured in skateboarding magazines.

BLDGBLOG: [laughs]

Michael Cook: Some of the largest pipe in the world is used as spillways for hydroelectric projects – big dams and that sort of thing – and usually the first people who find out about this stuff are skateboarders. Usually they try to keep the locations pretty quiet – just as we do. But I’m sure that, at least once or twice, some tunnel explorer has found out about a system through the skateboarding community.

[Image: Ottawa’s Governor General’s Drain].

[Image: Ottawa’s Governor General’s Drain].

BLDGBLOG: I’m also curious if there’s some huge, mythic system out there that you’ve heard about but haven’t visited yet, or even just an urban legend about some tunnels that may not actually be real – secret government bunkers in London, for instance.

Michael Cook: I guess the most fabled tunnel system in North America is the one that supposedly runs beneath old Victoria, British Columbia. It’s supposedly connected with Satanic activity or Masonic activity in the city, and there’s been a lot of strange stuff written about that. But no one’s found the great big Satanic system where they make all the sacrifices.

You know, these legends are really… there’s always some sort of fact behind them. How they come about and what sort of meaning they have for the community is what’s really interesting. So while I can poke fun at them, I actually appreciate their value – and, certainly, these sort of things are rumored in a lot of cities, not just Victoria. They’re in the back consciousness of a lot of cities in North America.

[Image: “Looking into the bottom of the William B. Rankine G.S. wheelpit from the Rankine tailrace“].

[Image: “Looking into the bottom of the William B. Rankine G.S. wheelpit from the Rankine tailrace“].

BLDGBLOG: Is there some system – a real system – that you’re really dying to explore?

Michael Cook: If I had unlimited funds, I’d really like to make a trip to South America and see some of the underground workings beneath Rio and São Paulo and Montevideo; and I want to go to Africa for a lot reasons but, obviously, it would also be really neat to see what’s built under some of the larger cities in Africa. It’s a place of real cleavages between modern development and the complete impossibility of expanding that development to the entire population. So great sums of money have been wasted on huge highway projects and huge downtown core projects that were completely unnecessary for anything other than creating the semblance of a modern city – but, undoubtedly, there’s subterranean infrastructure connected to all of it.

BLDGBLOG: As well as abandoned pieces of infrastructure just sitting up there on the surface – unused highway overpasses and derelict stadiums and things like that.

Michael Cook: Definitely. And huge mine workings, as well, in certain parts of Africa, that have been shut down.

[Image: Inside a distributor tunnel at the Ontario Generating Station drain; meanwhile, I can’t help but imagine what it’d be like if architects began building hotel lobbies like this: you check into your boutique hotel in London – and nearly pass out in awe…].

[Image: Inside a distributor tunnel at the Ontario Generating Station drain; meanwhile, I can’t help but imagine what it’d be like if architects began building hotel lobbies like this: you check into your boutique hotel in London – and nearly pass out in awe…].

BLDGBLOG: Meanwhile, urban exploration seems to be getting a lot of media attention these days – this interview included. How do you feel when you see articles in The New York Times about people exploring tunnels and drains?

Michael Cook: The problem I have with general interest reporting is that it almost invariably becomes, you know: look at this, isn’t this weird. Because that’s the easiest way of presenting what we do. It’s not about anything else – it’s entertainment.

So I’ve never really been interested in taking part in articles like that. They happen all the time in various places around the continent. Somewhere, there’s always a reporter who needs to file a story this week, or this month, and so they find an urban exploration site on the internet and they think, hey, that’s a great thing to write about, and then I can fill my quota. It’s not even that what they’re going to write is false or misleading, but it ultimately presents an incomplete and slightly cheapening image of what we do – and, in the end, it doesn’t really accomplish that much.

I think what I’m getting at is that the format of the newspaper article or the television news feature ultimately waters all this down and forces it into a specific block – that, while true of a certain segment of urban exploration, isn’t really representative of the whole. It has the effect of pigeon-holing the whole endeavor in a way.

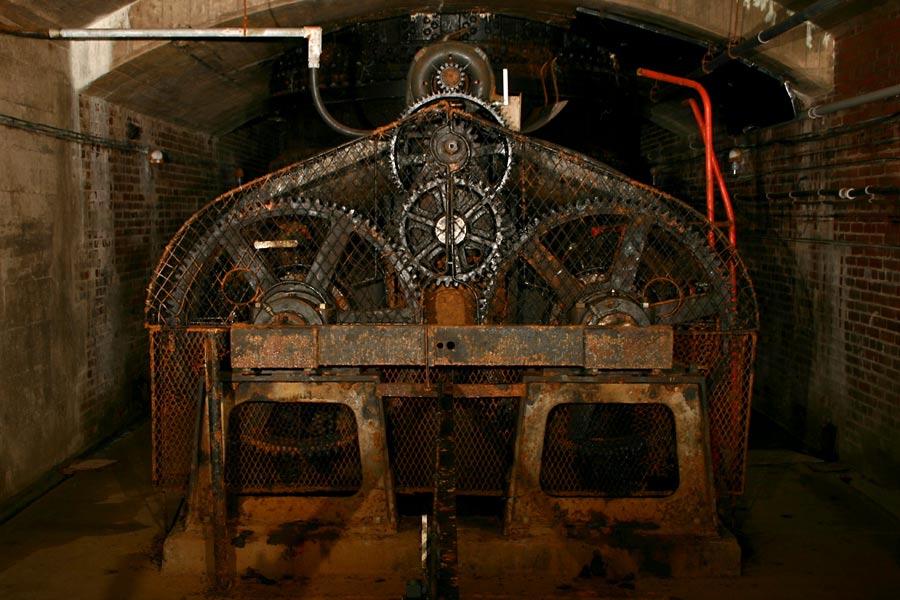

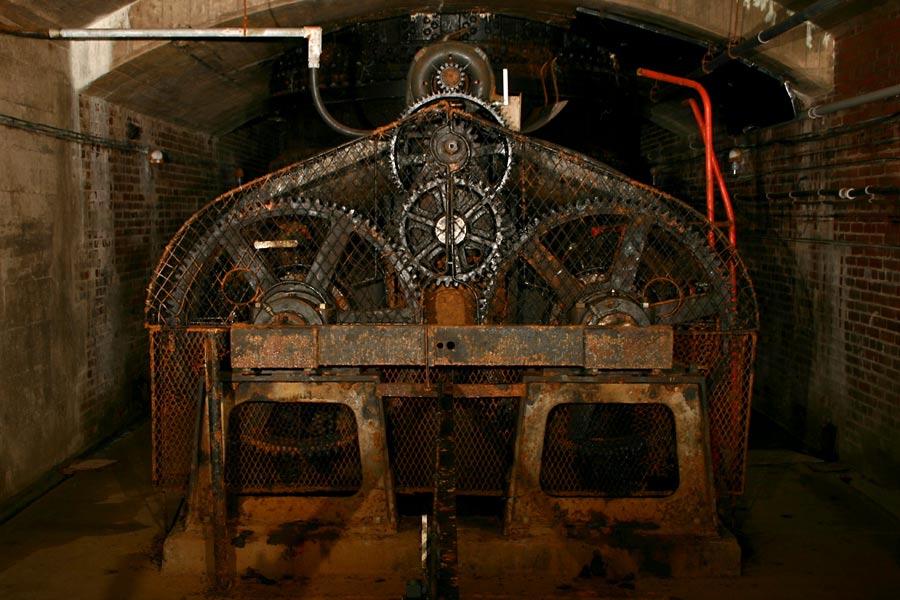

[Images: Disused hydroelectric machinery: top/bottom].

[Images: Disused hydroelectric machinery: top/bottom].

BLDGBLOG: That implies that there’s a way of looking at all this that you think needs more exposure. What parts of urban exploration should the media actually be covering?

Michael Cook: I think, even among explorers, that we don’t pay enough attention to process. I think every piece of infrastructure – every building – is on a trajectory, and you’re experiencing it at just one moment in its very extended life.

We see things, but we don’t often ask how they came about or where they’re going to go from here – whether there will be structural deterioration, or if living things will colonize the structure. We tend to ignore these things, or to see them in temporal isolation. We also don’t give enough time or consideration to how this infrastructure fits into the broader urban fabric, within the history of a city, and where that city’s going, and whose lives have been affected by it and whatever may happen to it in the future. I think these are all stories that really need to start being told.

Which is something I’m starting on. It’s just not something that necessarily comes naturally. It requires a lot of work, and a lot of thought while you’re on-site – which maybe you’re not really inclined to do, because you’re too busy paying attention to the immediate, sublime nature of the experience.

But the basic linear photo gallery really bores me at this point – especially when you’re seeing basically the same photos, just taken inside different buildings. It has no real, lasting value. A lot of people have fallen into that trap, and a lot of people defend that – saying that they’re making art or whatever, or that it’s just for their own personal interest.

BLDGBLOG: So it’s a matter of paying attention both to the site’s history and to how your own documentation of that site will someday be used as history.

Michael Cook: If you decide to take a purely historical approach to it, though, I think the real question is: are these photos of asylum hallways and drainage tunnels ultimately going to be useful to anyone else at some point in the future? And the answer is probably not. Probably we’re photographing the wrong things for that.

Some architect or materials historian is going to be cursing us for photographing some things and not others, or for not taking a close-up of something – or for not writing down any supplementary information at all to help them identify this stuff.

So that historical angle, to justify some of the stuff we’re doing, falls down on further analysis.

[Image: Abandoned cash registers].

[Image: Abandoned cash registers].

BLDGBLOG: It’s like bad archaeology.

Michael Cook: What’s that?

BLDGBLOG: It’s like bad archaeology.

Michael Cook: Yeah, basically. It’s like we’re just digging things up and not paying attention to where they were placed, or what they were next to, or who might have put it there.

Ultimately, we need some sort of framework, and to put more effort into additional information beside just taking a photo. That doesn’t necessarily mean publishing all that information so that everyone can see it – but just telling stories in other ways, and creating narratives about the places and the things that we’re seeing.

Otherwise, these are just postcard shots. We’re taking postcard shots of the sublime.

[Image: Inside The Skin of a Lion, Toronto].

[Image: Inside The Skin of a Lion, Toronto].

• • •While we were editing the transcript for publication, Michael wrote:

I got into the storm sewer I mentioned [at the beginning of the interview], shortly after talking to you. It’s now on the site as Sisters of Mercy. Similar to Pilgrimage, it ends in a siphon, rather than a traversable passage into the Western Beaches Storage Tunnel, which I’m still working on finding. We’ve started exploring combined sewers as well here – so that opens up some other options. In the end, the access I found was directly above where the siphon begins, quite close to the lake.

So the explorations continue.

With a big thanks to Michael Cook for having this conversation – and for maintaining such a great website.

[Image: The “Three Musketeers” standing inside Toronto’s Westview Greenbelt Drain; Michael Cook is the one on the right; one of the other two is Siologen].

[Image: The “Three Musketeers” standing inside Toronto’s Westview Greenbelt Drain; Michael Cook is the one on the right; one of the other two is Siologen].

For a few more images, meanwhile, check out Vanishing Point – in particular, stop by the Daily Underground).

(More underground worlds and urban exploration on BLDGBLOG: Urban Knot Theory, London Topological, Derinkuyu, or: the allure of the underground city, Beneath the Neon, Valvescape, Subterranean bunker-cities, and Tunnels, mines, and the “upwardly migrating void”).

[Image: An airplane flies above Los Angeles, a landscape of now-forgotten airports].

[Image: An airplane flies above Los Angeles, a landscape of now-forgotten airports]. [Image: The now-lost runways of L.A.’s Cecil B. De Mille Airfield; photo courtesy of UCLA’s Re-Mapping Hollywood archive].

[Image: The now-lost runways of L.A.’s Cecil B. De Mille Airfield; photo courtesy of UCLA’s Re-Mapping Hollywood archive]. [Image: Charlie Chaplin Airfield in 1920s Los Angeles; photo courtesy of UCLA’s Re-Mapping Hollywood archive].

[Image: Charlie Chaplin Airfield in 1920s Los Angeles; photo courtesy of UCLA’s Re-Mapping Hollywood archive]. [Image: The Cecil B. De Mille Airfield, renamed Rogers Airport (or, possibly, Rogers Airport, which later became the Cecil B. De Mille Airfield); image via Paul Freeman’s Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields].

[Image: The Cecil B. De Mille Airfield, renamed Rogers Airport (or, possibly, Rogers Airport, which later became the Cecil B. De Mille Airfield); image via Paul Freeman’s Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields]. If you could design a bridge across the Bering Strait, connecting the U.S. to Russia, what would it look like? Come up with something good and you could win as much as $80,000 ($20,000, if you’re a student).

If you could design a bridge across the Bering Strait, connecting the U.S. to Russia, what would it look like? Come up with something good and you could win as much as $80,000 ($20,000, if you’re a student).  [Image: Offshore energy islands, via

[Image: Offshore energy islands, via  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: From Michael Winterbottom’s

[Image: From Michael Winterbottom’s  [Image: Shanghai, from

[Image: Shanghai, from  [Image: Shanghai, from

[Image: Shanghai, from  [Image: The Shanghai skyline, from

[Image: The Shanghai skyline, from  [Image: The opening titles of Michael Winterbottom’s

[Image: The opening titles of Michael Winterbottom’s  [Image: An etching by

[Image: An etching by

[Images: The Vatnsmýri airport grounds, Reykjavík, Iceland. Photos courtesy of the

[Images: The Vatnsmýri airport grounds, Reykjavík, Iceland. Photos courtesy of the  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By

[Images: By

[Images: By

[Images: By

[Images: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By

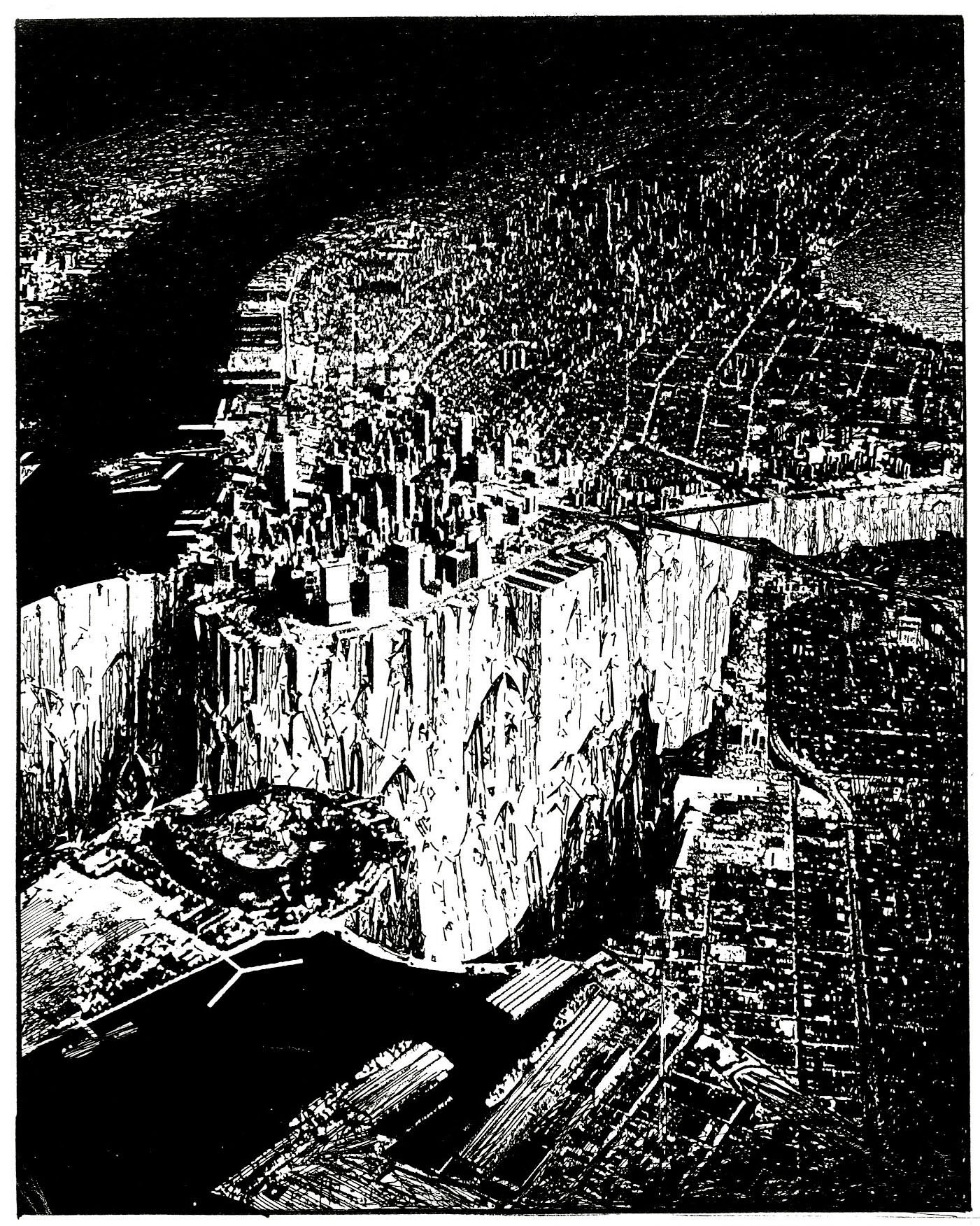

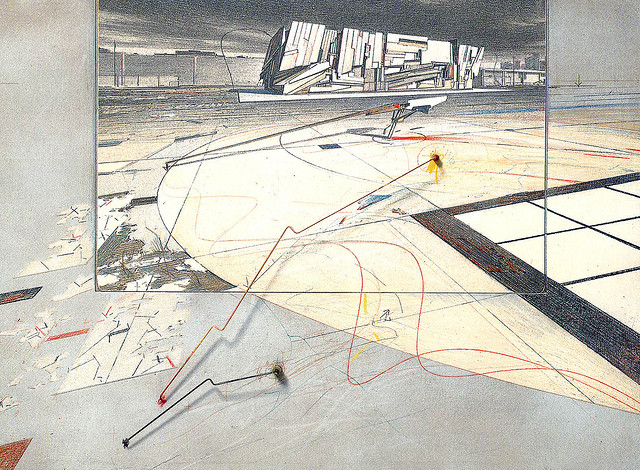

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999; view

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999; view  [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, radically reconstructed, 1994].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, radically reconstructed, 1994]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, DMZ, 1988].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, DMZ, 1988].

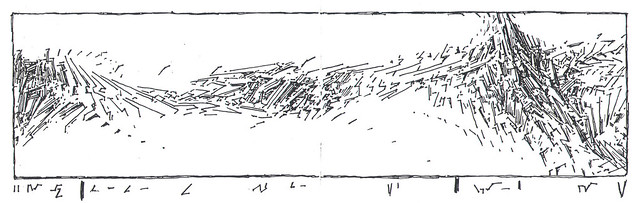

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, the city and the faults it sits on, from the San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, the city and the faults it sits on, from the San Francisco Bay Project, 1995]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, 1994; view

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Havana, 1994; view  [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999, in case you missed it; view

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Lower Manhattan, 1999, in case you missed it; view

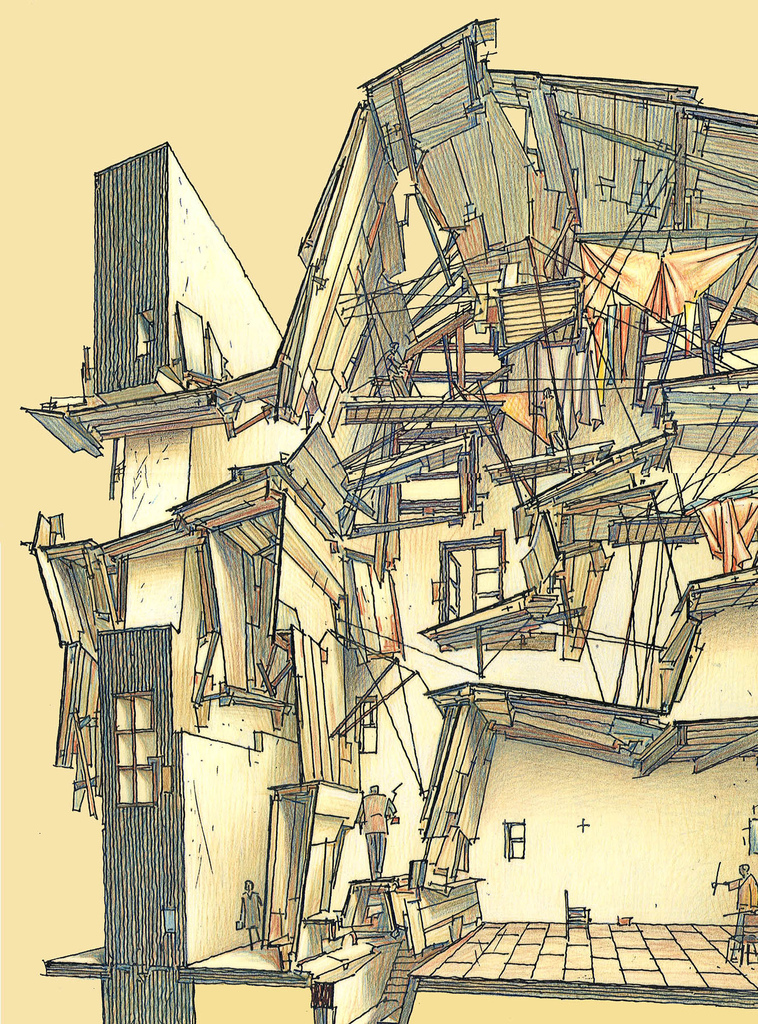

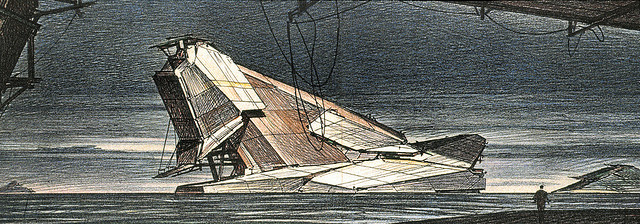

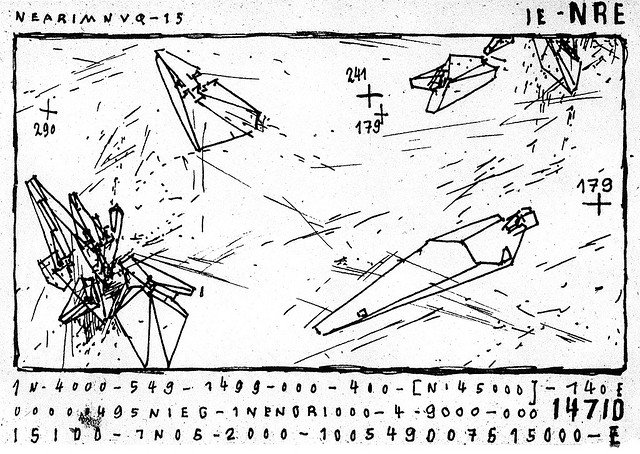

[Images: Lebbeus Woods. Future structures of the Korean demilitarized zone (1988) juxtaposed with two views of the architectonic tip of some vast flooded machine-building, from Icebergs (1991)].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods. Future structures of the Korean demilitarized zone (1988) juxtaposed with two views of the architectonic tip of some vast flooded machine-building, from Icebergs (1991)].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, The Wall Game].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, The Wall Game]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods, Siteline Vienna, 1998].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods, Siteline Vienna, 1998].

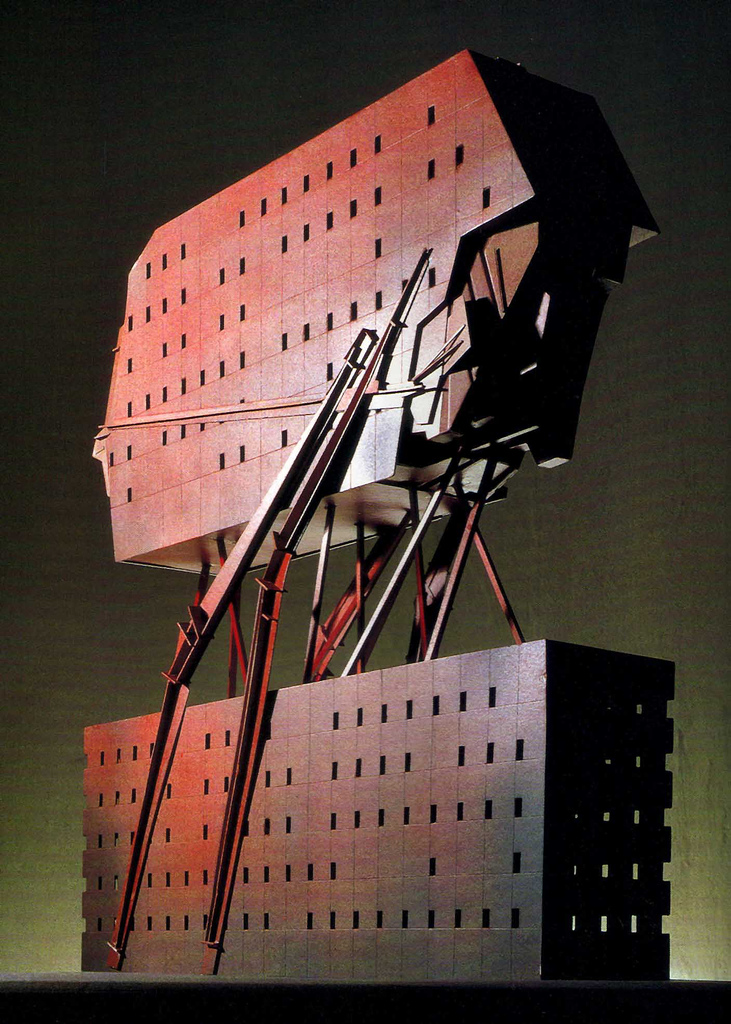

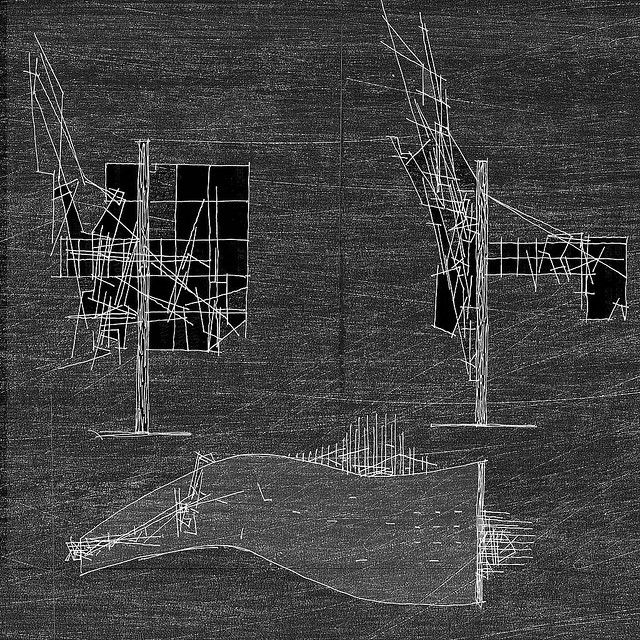

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, Nine Reconstructed Boxes].

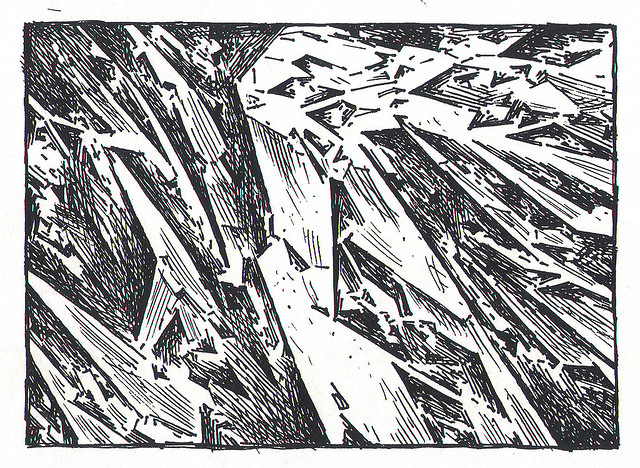

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, Nine Reconstructed Boxes]. [Image: Lebbeus Woods. A drawing of tectonic faults and other subsurface tensions, from his San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

[Image: Lebbeus Woods. A drawing of tectonic faults and other subsurface tensions, from his San Francisco Bay Project, 1995].

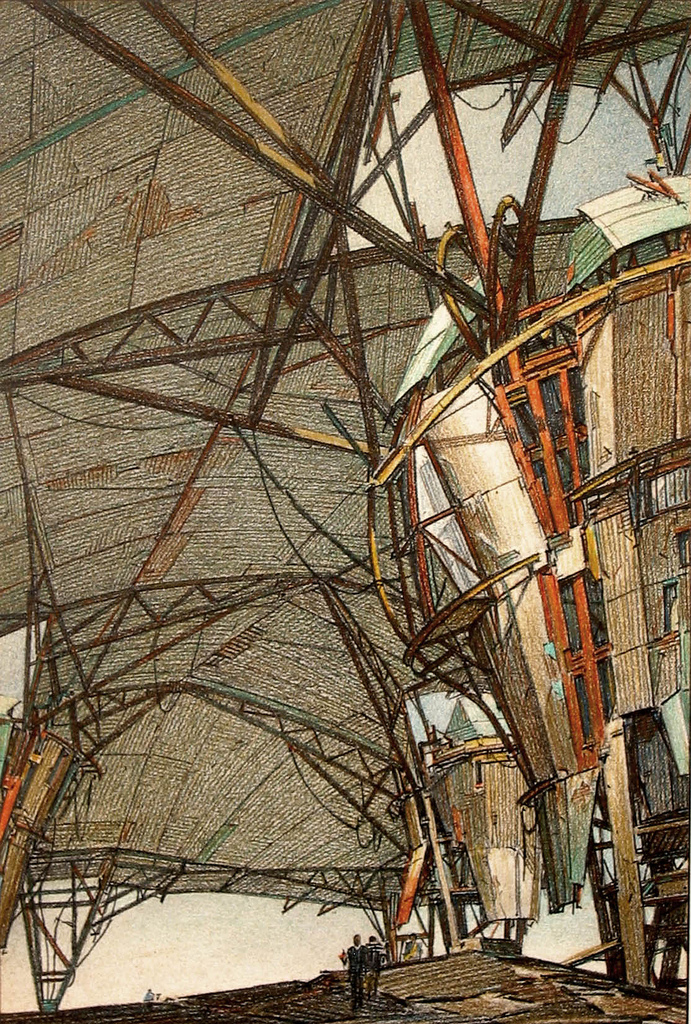

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, System Wien, 2005].

[Images: Lebbeus Woods, System Wien, 2005]. [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The Memorial Park Storage Chambers in Toronto’s

[Image: The Memorial Park Storage Chambers in Toronto’s  [Image: “Stairs” by Michael Cook, from the

[Image: “Stairs” by Michael Cook, from the

[Images: (top) “Transition to CMP,” from Toronto’s

[Images: (top) “Transition to CMP,” from Toronto’s  [Image: “Emerging in Wilson Heights,” out of Toronto’s

[Image: “Emerging in Wilson Heights,” out of Toronto’s  [Image: The outfall of Toronto’s

[Image: The outfall of Toronto’s  [Image: An “A-shaped conduit” in Toronto’s

[Image: An “A-shaped conduit” in Toronto’s

[Image: (top) “Outfall structure in the West Don Valley,” part of Toronto’s

[Image: (top) “Outfall structure in the West Don Valley,” part of Toronto’s  [Image: “Outfall in winter” at Toronto’s

[Image: “Outfall in winter” at Toronto’s  [Image: Looking out of a spillway at the

[Image: Looking out of a spillway at the  [Image: The “spectacular, formerly natural waterfall that the [

[Image: The “spectacular, formerly natural waterfall that the [ [Images: A “short drop” in Toronto’s beautifully torqued and ovoid

[Images: A “short drop” in Toronto’s beautifully torqued and ovoid

[Images: Four glimpses of the vaulted topologies installed inside the Earth at Niagara’s

[Images: Four glimpses of the vaulted topologies installed inside the Earth at Niagara’s

[Images: (top) Leaving the

[Images: (top) Leaving the  [Image: “Transitions” inside the

[Image: “Transitions” inside the  [Image: “Deep inside the century-old wheelpit that is the beginning of the

[Image: “Deep inside the century-old wheelpit that is the beginning of the  [Image: Ottawa’s

[Image: Ottawa’s  [Image: “Looking into the bottom of the William B. Rankine G.S. wheelpit from

[Image: “Looking into the bottom of the William B. Rankine G.S. wheelpit from  [Image: Inside a distributor tunnel at the

[Image: Inside a distributor tunnel at the

[Images: Disused hydroelectric machinery:

[Images: Disused hydroelectric machinery:  [Image: Abandoned cash registers].

[Image: Abandoned cash registers]. [Image: Inside

[Image: Inside  [Image: The “

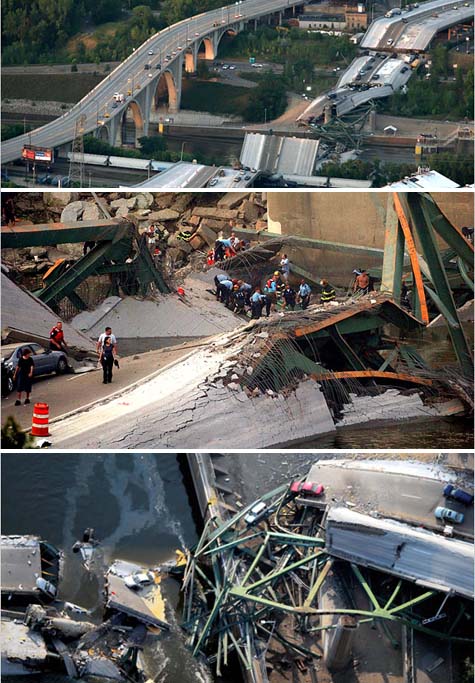

[Image: The “ [Image: Photo by Allen Brisson-Smith for

[Image: Photo by Allen Brisson-Smith for  [Image: Photo by Jeff Wheeler/The Star Tribune/AP; via

[Image: Photo by Jeff Wheeler/The Star Tribune/AP; via  [Image: Photo by Heather Munro/The Star Tribune/AP; via

[Image: Photo by Heather Munro/The Star Tribune/AP; via  [Images: Photos courtesy of

[Images: Photos courtesy of  [Image: Jeffrey Inaba].

[Image: Jeffrey Inaba]. [Image: A page-spread from Volume 10].

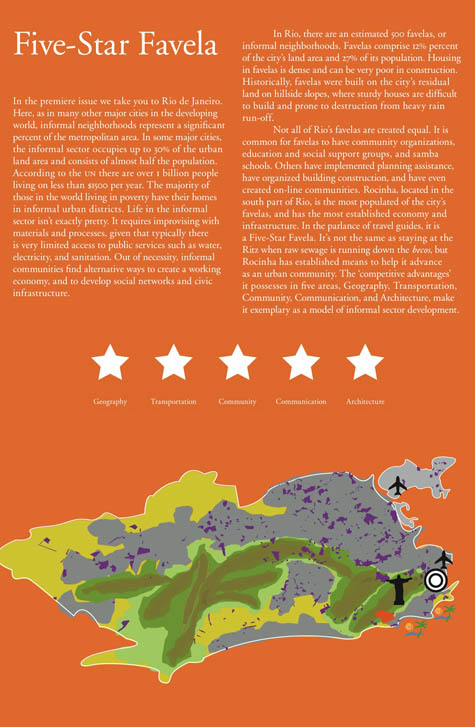

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 10]. [Image: The cover page of Alibi, from Volume 10. For more on favelas, meanwhile, don’t miss BLDGBLOG’s earlier, two-part interview with

[Image: The cover page of Alibi, from Volume 10. For more on favelas, meanwhile, don’t miss BLDGBLOG’s earlier, two-part interview with  [Image: A page-spread from Volume 10].

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 10]. [Image: A page-spread from Volume 10].

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 10]. [Image: A page-spread from Volume 6].

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 6]. [Image: A page-spread from Volume 6].

[Image: A page-spread from Volume 6]. [Image: Two pages from Volume 6].

[Image: Two pages from Volume 6]. [Image: A page from Volume 10].

[Image: A page from Volume 10].