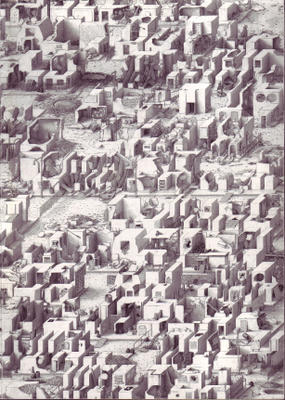

I just found an old article from frieze about graphic artist Paul Noble‘s “monumental eight-year project… [to create] a fictional city called Nobson Newtown.”

Nobson Newtown was an “exercise in self-portraiture via town planning,” involving “the painstaking design of a special font based on the forms of classic modernist architecture.”

The “city,” in other words, was made of words.

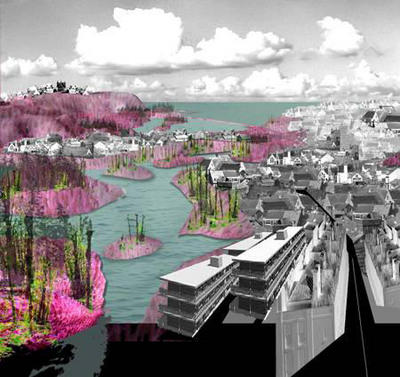

“Variously described as ‘3-D Scrabble tiles’ or ‘Lego blocks’, Noble’s pictograms name the buildings that they depict. From the hospital (Nobspital) to the cemetery (Nobsend) via the town centre (Nobson Central) or the Mall, citations from Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat, Gerard Winstanley’s letters to Oliver Cromwell or T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland are camouflaged within the fields, the trees or the brickwork. Noble’s project embodies a complex infrastructure of civil planning, social policies and historical perspectives” – and it was all done with pencil. (Book available here).

“At first,” says the BBC, “the drawings appear to be depictions of a crazy Babylonian society, with a touch of Brueghel’s Tower Of Babel and Robert Crumb’s rounded comic strips. Then you realise each building is also a 3-D letter of the alphabet spelling out hard to decipher sentences in Noble’s self-created Nobfont.”

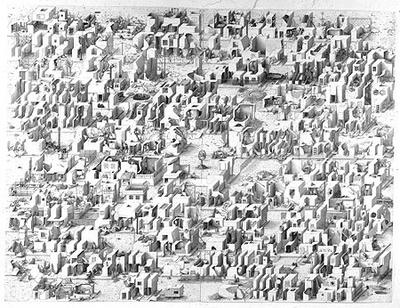

But he wasn’t the first.

Nearly two decades earlier, in 1980, Steven Holl published his own “Alphabetical City” through Pamphlet Architecture, and it, too, consisted entirely of buildings that were actually letters, that were actually a city, that… – but the funny thing is, Holl’s drawings look absolutely, unpublishably stupid compared to Noble’s:

Hello? One wonders which two-minute lunch break Holl took to draw those… Or was it thirty seconds?

In any case, the creation of architectural space through a tweaking of the alphabet is not an inherently interesting proposition, but Noble’s eye-failure-inducing drawings reward repeated viewings. Just blink occasionally.

The buildings, frieze‘s Tom Morton claims, look like, “odd, wind-carved rock formations. Standing on higher ground, squinting against the sun, we’d see that they formed an eroded text.”

Here I’m reminded of the idea of “slow sculpture” from China Miéville’s novel, Iron Council:

“Huge sedimentary stones… each carefully prepared: shafts drilled precisely, caustic agents dripped in, for a slight and so-slow dissolution of rock in exact planes, so that over years of weathering, slabs would fall in layers, coming off with the rain, and at very last disclosing their long-planned shapes. Slow-sculptors never disclosed what they had prepared, and their art revealed itself only long after their deaths.”

Perhaps, in those dissolving rocks, you could plan a slow and secret alphabet…