[Image: From Acoustic Botany by David Benqué].

[Image: From Acoustic Botany by David Benqué].

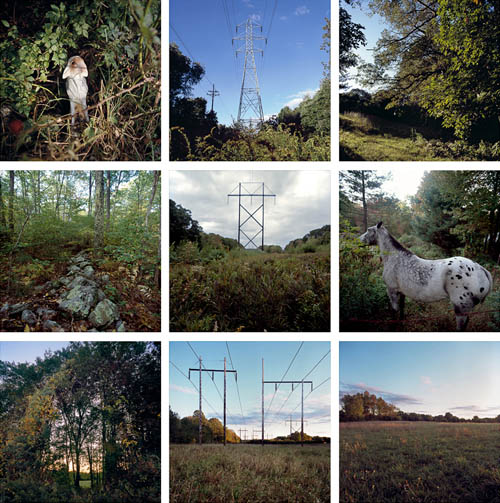

We saw David Benqué’s Fabulous Fabbers project here on BLDGBLOG a few months ago, but his more recent work, Acoustic Botany, deserves similar attention.

Acoustic Botany uses genetically modified plants to produce a “fantastical acoustic garden,” where sounds literally grow on trees. “Desired traits such as volume, timbre and harmony are acquired through selective breeding techniques,” the artist explains.

[Image: From Acoustic Botany by David Benqué].

[Image: From Acoustic Botany by David Benqué].

As Benqué writes:

The debate around Genetic Engineering is currently centered around vital issues such as food, healthcare and the environment. However, we have been shaping nature for thousands of years, not only to suit our needs, but our most irrational desires. Beautiful flowers, mind altering weeds and crabs shaped like human faces all thrive on these desires, giving them an evolutionary advantage. By presenting a fantastical acoustic garden, a controlled ecosystem of entertainment, I aim to explore our cultural and aesthetic relationship to nature, and to question its future in the age of Synthetic Biology.

There are thus “singing flowers,” “modified agrobacteria” that ingeniously take “sugars and nutrients from the host plant to encourage the growth of parasitic galls and fill them with gas to produce sound,” and “string-nut bugs” that have been “engineered to chew in rhythm” inside hollow gourds.

[Image: From Acoustic Botany by David Benqué].

[Image: From Acoustic Botany by David Benqué].

The symphonic range of sounds is then fine-tuned and modulated inside an acoustic lab using specialized equipment; out in the field, this takes the form of pruning trees into living chords, so that “harmonic note combinations” can bloom on a single branch.

Upscaling this to the level of all-out acoustic forestry would be an extraordinary thing to hear.

[Image: From Acoustic Botany by David Benqué].

[Image: From Acoustic Botany by David Benqué].

I’m reminded of at least two quick things here:

1) Several years ago in the excellent British music magazine The Wire, there was an article about Brian Eno and “generative music,” in which the acoustic nature of backyard gardens was described quite beautifully based on the seasonal popping of seedpods, the rustle of leaf-covered fronds in evening breezes, and even, if I remember correctly, the specific insects that such plants might attract and support. Does anyone reading this have experience with planting a backyard garden based on its future acoustics?

2) Alex Metcalf’s Tree Listening project (which I have also covered elsewhere). “The installation,” Metcalf writes, “allows you to listen to the water moving up inside the tree through the Xylem tubes from the roots to the leaves.” Headphones hang down from the tree’s canopy like botanical iPods, and you put them on to lose yourself in arboreal surroundsound. Imagine a shortwave radio that allows you to tune not into distant stations sparkling with disembodied sounds and buzzing voices from the other side of the world, but into the syrupy tides of trees spiked with microphones in forests and sacred groves on every continent.

More images of Benqué’s project can be seen on the artist’s website.

(Spotted on Core77, thanks to a tweet from @soundscrapers).

[Image: The Duplicative Forest—17,000 acres of identical trees—awaits; photo courtesy of

[Image: The Duplicative Forest—17,000 acres of identical trees—awaits; photo courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image: Courtesy of the

[Image: Courtesy of the  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image: