Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley, originally published on Edible Geography.

In a fantastic hybrid of edible architecture and temporary summer pavilion, architect Caroline O’Donnell has proposed Bloodline, a free-standing, self-consuming grilling shelter.

[Image: Sectional model through the preparation bench, Bloodline pavilion by Caroline O’Donnell; Bloodline is supported by the Akademie Schloss Solitude].

[Image: Sectional model through the preparation bench, Bloodline pavilion by Caroline O’Donnell; Bloodline is supported by the Akademie Schloss Solitude].

Bloodline is the outcome of O’Donnell’s 2007 fellowship and residency at Akademie Schloss Solitude, a grant-making and residency institution housed in the late-Baroque “Solitude Castle” near Stuttgart in southern Germany.

Karl Eugen, Duke of Württemburg, built Schloss Solitude in 1763 as a private pleasure house—a cross between a party castle, summer retreat, and hunting lodge. Solitude was intended to be more intimate and less formal than his royal palace at Ludwigsburg, like the Trianons were to Versailles.

[Image: Akademie Schloss Solitude, via Wikimedia].

[Image: Akademie Schloss Solitude, via Wikimedia].

Among the prerequisites for an eighteenth-century aristocrat to achieve relaxation were a natural setting and, perhaps more importantly, minimal interaction with the servant classes. However, since domestic service was still required (aristocratic relaxation did not encompass preparing, serving, and cleaning up after meals, for example), palace architects had to resort to an extremely elaborate set of spatial tricks and distortions to make the servers as invisible as possible. The original design for the Petit Trianon even included a mechanism for raising and lowering the dining table through the floor so that it could be set and cleared out of sight.

According to O’Donnell, “The guides at Schloss Solitude could not understand why I wanted to see the service spaces, and tried to convince me that they were not interesting. I kept telling them in bad German that I was an architect and therefore interested in uninteresting spaces, but that seemed to cause more confusion.”

[Image: The secret service spaces at Ludwigsburg (left) and Schloss Solitude (right)].

[Image: The secret service spaces at Ludwigsburg (left) and Schloss Solitude (right)].

What she found, eventually, were a series of awkward and cramped service cupboards and passages, filling in the spaces around the formal, symmetrical rooms. They are the negative space of pure classical order; the banished evidence of domestic effort and bodily needs.

Interestingly, O’Donnell noticed that at Karl Eugen’s main palace, Ludwigsburg Castle, the formal rooms are arranged around the edge, concealing a rabbit warren of service spaces in the interior.

Meanwhile at Solitude, the reverse is true: the cupboards, closets, and service passages are banished to the edge, with the result that seven of the fourteen windows on the perfectly symmetrical south façade actually open onto these deformed, hidden spaces.

[Images: (top) The south-facing façade of Schloss Solitude, in which seven of its windows actually open onto service spaces, rather than public rooms; via. (bottom) The negative spaces into which domestic functions were banished at Schloss Solitude (left); many were used as fire-spaces (right)].

[Images: (top) The south-facing façade of Schloss Solitude, in which seven of its windows actually open onto service spaces, rather than public rooms; via. (bottom) The negative spaces into which domestic functions were banished at Schloss Solitude (left); many were used as fire-spaces (right)].

Among the domestic functions concealed in this way was fire maintenance: tiny fire-spaces were used for storing firewood and also enabled servants to stoke open fires while remaining behind the scenes.

O’Donnell explained that when she finally gained access to a fire-space, she noticed “the effects of this small-scale and contorted space on the body,” but she was most fascinated “by this idea of the fire-space as a window, through which the stooping servant had a rare window into the lives of his masters”—and, in some ways, a more complete or privileged understanding of the space of the palace as a whole.

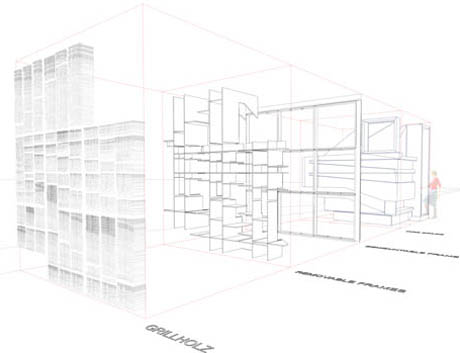

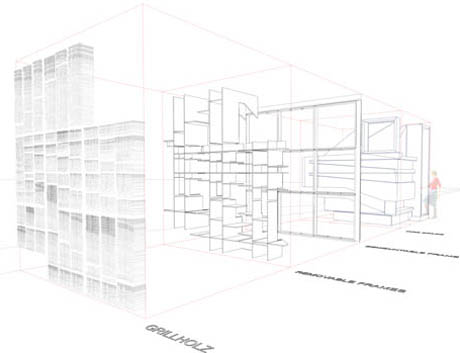

[Image: Bloodline, showing the stacked grillholz cuboid exterior concealing the irregular interior].

[Image: Bloodline, showing the stacked grillholz cuboid exterior concealing the irregular interior].

So, back to the barbecue pavilion: O’Donnell’s Bloodline proposal would use 360 bags of grillholz (German barbecue wood sticks) as the cladding—enough for a summer season, or ninety barbecues at four bags per cook-out. As July fades into August, and then into September, the pavilion will gradually be dismantled: the architecture’s fiery function will lead it to literally consume itself from the outside in. This is an incredibly poetic literalization of the shelter’s function: architecture parlante at its finest.

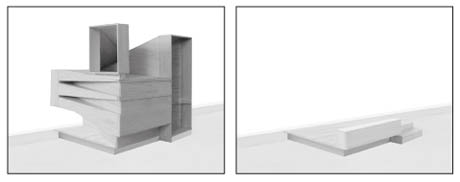

The pavilion also plays on O’Donnell’s initial fascination with Solitude’s squished fire-spaces. Bloodline begins the summer as a perfect, platonic cube, but gradually grills itself down to an awkwardly shaped frame that mirrors a section through the original fire-space. In other words, through use, the mini-barbecue palace will reveal its contorted, service-space origins—a slow, season-long process of revelation.

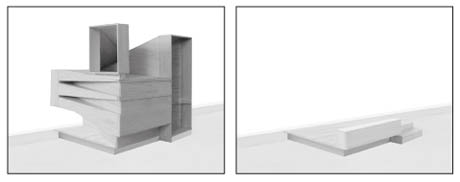

[Image: The pavilion will begin the summer as a platonic cube before being eroded through repeated barbecuing to reveal its hidden fire-space form].

[Image: The pavilion will begin the summer as a platonic cube before being eroded through repeated barbecuing to reveal its hidden fire-space form].

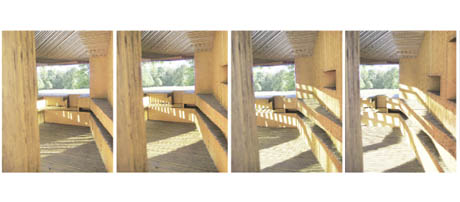

Like Solitude’s original fire-spaces, which servants had to bend down and crawl to enter, the Bloodline barbecue pavilion is only designed to fit one person. And, as in the originals, that one person—the servant or barbecuer-in-chief, depending on how you look at these things—has a unique, more omniscient view.

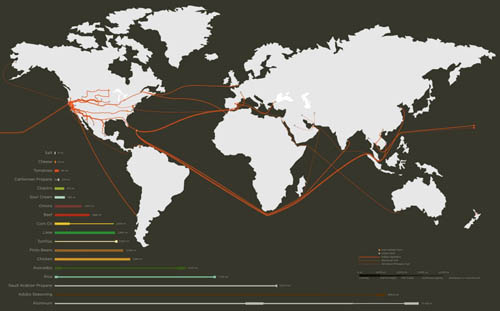

Ludwigsburg and Solitude castles are linked by Solitudeallee, each palace is also aligned on its own axis of symmetry. When O’Donnell looked at these lines in satellite view, it became clear that there was a third axis, emerging from the forest, which was missing a castle.

Ingeniously, O’Donnell’s proposed site for Bloodline means that our barbecuing hero, standing in front of the grill-window on the southwest-facing side of the pavilion, is the only person in their party who can see that they are actually inside the missing third castle.

[Image: Plotting the axes and intersections of Ludwigsburg and Solitude: O’Donnell explained that “only the forest is missing a castle”].

[Image: Plotting the axes and intersections of Ludwigsburg and Solitude: O’Donnell explained that “only the forest is missing a castle”].

In other words, while their friends and family relax in the grounds outside the pavilion, eating sausages they haven’t had to prepare, “only the servant (or grill-master) will know the truth,” explains O’Donnell, “although they can sneak others in, to share the secret.”

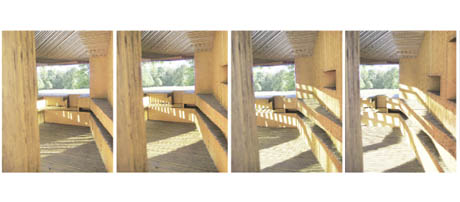

[Images: (top) Renderings of Bloodline show the grill-window and entrance; (bottom) Bloodline interior, looking out toward the grill-window’s privileged view].

[Images: (top) Renderings of Bloodline show the grill-window and entrance; (bottom) Bloodline interior, looking out toward the grill-window’s privileged view].

In terms of grilling experience, the barbecue pavilion that becomes a secret, personal castle seems second to none. “After that, the sausages are not my responsibility,” O’Donnell told me. “There are however custom spaces built into the pavilion on the west side for a fire-extinguisher and a fire-blanket, as well as a big vent on the east side that aligns with the prevailing wind and uses the stack-effect to ventilate the space naturally.”

A couple of thoughts immediately come to mind here: firstly, that this is the perfect Father’s Day gift. After all, doesn’t every red-blooded male secretly crave his own barbecue castle: a private space of solitude, unspoken power, and burger perfection? Lowe’s or Homebase could even stock build-your-own kits, for an extra DIY frisson.

[Image: (left) Inside Bloodline (the server has clearly snuck in a few friends); (right) Stacked grillholz will form the façade and the barbecue fuel. The wood sticks’ color even matches the ochre putty exterior of Schloss Solitude].

[Image: (left) Inside Bloodline (the server has clearly snuck in a few friends); (right) Stacked grillholz will form the façade and the barbecue fuel. The wood sticks’ color even matches the ochre putty exterior of Schloss Solitude].

I’m also reminded, via a link that was (coincidentally?) sent to me separately by Caroline O’Donnell, of Harvard anthropologist Richard Wrangham‘s theory that cooking is the root cause of human civilization. His basic idea is that the discovery of cooking allowed us to unlock many more calories in food, which gave us more energy for less effort, which in turn resulted in a massive increase in brain size in Homo sapiens (as compared to our primate ancestors).

[Images: Stages of consumption. At the end, all that will remain is the ash bench (bottom right), which O’Donnell plans to leave on site once the summer is over, “as a clue to the missing castle”].

[Images: Stages of consumption. At the end, all that will remain is the ash bench (bottom right), which O’Donnell plans to leave on site once the summer is over, “as a clue to the missing castle”].

That expanded brain of course led, eventually, to the flowering of the Baroque, in which rococo pleasure palaces were cleverly designed to hide any evidence of cooking facilities. O’Donnell’s pavilion gives cooking its due once again, as over the course of the summer Solitude’s missing third palace is revealed to be a a functional fire-space, rather than the abstracted perfection of a symmetrical cube. Barbecuing German day-trippers will thus be paying inadvertent homage to the role of fire in human civilization.

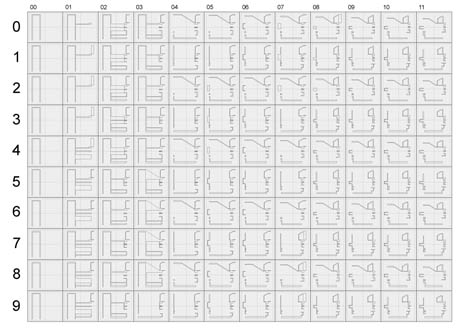

[Image: Some of O’Donnell’s incredibly complex cut files for fabrication].

[Image: Some of O’Donnell’s incredibly complex cut files for fabrication].

Caroline O’Donnell is working with Akademie Schloss Solitude to secure funding for the pavilion: the hope is to install it during the summer of 2011. My thanks are due to her for an incredibly interesting conversation, and also to Nathan Friedman, who has been working on Bloodline with O’Donnell for the past few months.

(Note: This post, written by Nicola Twilley, was originally published on Edible Geography).

[Image: Courtesy of Carnegie Mellon’s Morphing Matter Lab, via New Scientist.]

[Image: Courtesy of Carnegie Mellon’s Morphing Matter Lab, via New Scientist.] [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: Nikola Tesla, perhaps daydreaming of mushrooms; courtesy Wellcome Library.]

[Image: Nikola Tesla, perhaps daydreaming of mushrooms; courtesy Wellcome Library.]  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: An augmented-eating apparatus from “

[Image: An augmented-eating apparatus from “ [Image: From a previous

[Image: From a previous  [Image: From a previous

[Image: From a previous  [Images: Photos from previous

[Images: Photos from previous  [Image: From a previous

[Image: From a previous  Like a culinary version of

Like a culinary version of  [Image: “There are two basic types of taco trucks,” we read; “the first and most common is the transient truck which is a truck that stops at approximately 20 different locations at 20-minute intervals during an 8-hour shift, typically beginning at 6am and ending at 2pm. The second type is the semi-permanent truck, which is a truck that has found a location that has a density of clientele to sustain it for an extended period of the day, creating a nearly fixed presence in a particular community.” From

[Image: “There are two basic types of taco trucks,” we read; “the first and most common is the transient truck which is a truck that stops at approximately 20 different locations at 20-minute intervals during an 8-hour shift, typically beginning at 6am and ending at 2pm. The second type is the semi-permanent truck, which is a truck that has found a location that has a density of clientele to sustain it for an extended period of the day, creating a nearly fixed presence in a particular community.” From  [Image: Sectional model through the preparation bench, Bloodline pavilion by

[Image: Sectional model through the preparation bench, Bloodline pavilion by  [Image: Akademie Schloss Solitude, via

[Image: Akademie Schloss Solitude, via  [Image: The secret service spaces at Ludwigsburg (left) and Schloss Solitude (right)].

[Image: The secret service spaces at Ludwigsburg (left) and Schloss Solitude (right)].

[Images: (top) The south-facing façade of Schloss Solitude, in which seven of its windows actually open onto service spaces, rather than public rooms;

[Images: (top) The south-facing façade of Schloss Solitude, in which seven of its windows actually open onto service spaces, rather than public rooms;  [Image: Bloodline, showing the stacked grillholz cuboid exterior concealing the irregular interior].

[Image: Bloodline, showing the stacked grillholz cuboid exterior concealing the irregular interior]. [Image: The pavilion will begin the summer as a platonic cube before being eroded through repeated barbecuing to reveal its hidden fire-space form].

[Image: The pavilion will begin the summer as a platonic cube before being eroded through repeated barbecuing to reveal its hidden fire-space form]. [Image: Plotting the axes and intersections of Ludwigsburg and Solitude: O’Donnell explained that “only the forest is missing a castle”].

[Image: Plotting the axes and intersections of Ludwigsburg and Solitude: O’Donnell explained that “only the forest is missing a castle”].

[Images: (top) Renderings of Bloodline show the grill-window and entrance; (bottom) Bloodline interior, looking out toward the grill-window’s privileged view].

[Images: (top) Renderings of Bloodline show the grill-window and entrance; (bottom) Bloodline interior, looking out toward the grill-window’s privileged view]. [Image: (left) Inside Bloodline (the server has clearly snuck in a few friends); (right) Stacked grillholz will form the façade and the barbecue fuel. The wood sticks’ color even matches the ochre putty exterior of Schloss Solitude].

[Image: (left) Inside Bloodline (the server has clearly snuck in a few friends); (right) Stacked grillholz will form the façade and the barbecue fuel. The wood sticks’ color even matches the ochre putty exterior of Schloss Solitude].

[Images: Stages of consumption. At the end, all that will remain is the ash bench (bottom right), which O’Donnell plans to leave on site once the summer is over, “as a clue to the missing castle”].

[Images: Stages of consumption. At the end, all that will remain is the ash bench (bottom right), which O’Donnell plans to leave on site once the summer is over, “as a clue to the missing castle”]. [Image: Some of O’Donnell’s incredibly complex cut files for fabrication].

[Image: Some of O’Donnell’s incredibly complex cut files for fabrication]. [Image: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel. All photos by the

[Image: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel. All photos by the  [Image: The mushroom tunnel, on the left, was originally built in 1886 to house a single-track railway line. By 1919, it had to be replaced with the still-functioning double-track tunnel to its right, built to cope with the rise in traffic on the route following the founding of

[Image: The mushroom tunnel, on the left, was originally built in 1886 to house a single-track railway line. By 1919, it had to be replaced with the still-functioning double-track tunnel to its right, built to cope with the rise in traffic on the route following the founding of

[Images: (top) Dr. Arrold with a bag of mushroom spawn. He keeps his mushroom cultures in test-tubes filled with boiled potato and agar, and initially incubates the spawn on rye or wheat grains in clear plastic bags sealed with sponge anti-mould filters before transferring it to jars, black bin bags, or plastic-wrapped logs; (middle) Shimeji and (bottom) pink oyster mushrooms cropping on racks inside the tunnel. Dr. Arrold came up with the simple but clever idea of growing mushrooms in black bin bags with holes cut in them. Previously, mushrooms were typically grown inside clear plastic bags. The equal exposure to light meant that the mushrooms fruited all over, which made it harder to harvest without missing some].

[Images: (top) Dr. Arrold with a bag of mushroom spawn. He keeps his mushroom cultures in test-tubes filled with boiled potato and agar, and initially incubates the spawn on rye or wheat grains in clear plastic bags sealed with sponge anti-mould filters before transferring it to jars, black bin bags, or plastic-wrapped logs; (middle) Shimeji and (bottom) pink oyster mushrooms cropping on racks inside the tunnel. Dr. Arrold came up with the simple but clever idea of growing mushrooms in black bin bags with holes cut in them. Previously, mushrooms were typically grown inside clear plastic bags. The equal exposure to light meant that the mushrooms fruited all over, which made it harder to harvest without missing some].

[Images: (top) Logs on racks (Taiwanese style) and mounted on the wall (Chinese style) in the tunnel; (bottom) Wood-ear mushrooms grow through diagonal slashes in plastic bags filled with chopped wheat straw].

[Images: (top) Logs on racks (Taiwanese style) and mounted on the wall (Chinese style) in the tunnel; (bottom) Wood-ear mushrooms grow through diagonal slashes in plastic bags filled with chopped wheat straw]. [Image: Renderings of Fabric’s “Tower of Atmospheric Relations,” showing the stacked volumes of air and the resulting climate simulations].

[Image: Renderings of Fabric’s “Tower of Atmospheric Relations,” showing the stacked volumes of air and the resulting climate simulations].

[Images: (top) Li-Sun employees unwrap mushroom logs before putting them on racks in the tunnel. The logs are made by mixing steamed bran or wheat, sawdust from thirty-year-old eucalyptus, and lime in a concrete mixer, packing it into plastic cylinders, and inoculating them with spawn. (middle) Fruiting Shiitake logs on racks in the tunnel. Once their mushrooms are harvested, the logs make great firewood. (bottom) The Shiitake log shock tank – Dr. Arrold explained that the logs crop after one week in the tunnel, and then sit dormant for three weeks, until they are “woken up” with a quick soak in a tub of water, after which they are productive for three or four more weeks. “Shiitake,” said Dr. Arrold, in a resigned tone, “are the most trouble – and the biggest market.”]

[Images: (top) Li-Sun employees unwrap mushroom logs before putting them on racks in the tunnel. The logs are made by mixing steamed bran or wheat, sawdust from thirty-year-old eucalyptus, and lime in a concrete mixer, packing it into plastic cylinders, and inoculating them with spawn. (middle) Fruiting Shiitake logs on racks in the tunnel. Once their mushrooms are harvested, the logs make great firewood. (bottom) The Shiitake log shock tank – Dr. Arrold explained that the logs crop after one week in the tunnel, and then sit dormant for three weeks, until they are “woken up” with a quick soak in a tub of water, after which they are productive for three or four more weeks. “Shiitake,” said Dr. Arrold, in a resigned tone, “are the most trouble – and the biggest market.”]

[Images: (top) The paper cone around the top of the enoki jar helps the mushrooms grow tall and thin. (second) Chestnut mushrooms grow in jars for seven weeks: four to fruit, and three more to sprout to harvest size above the jar’s rim. (third) Thousands of mushroom jars are stacked from floor to ceiling. Dr. Arrold starting growing these mushroom varieties in jars two years ago, and hasn’t had a holiday since. (fourth) Empty mushroom jars are sterilised in the autoclave between crops, so that disease doesn’t build up. (bottom) The clean jars are filled with sterilised substrate using a Japanese-designed machine, before being inoculated with spawn].

[Images: (top) The paper cone around the top of the enoki jar helps the mushrooms grow tall and thin. (second) Chestnut mushrooms grow in jars for seven weeks: four to fruit, and three more to sprout to harvest size above the jar’s rim. (third) Thousands of mushroom jars are stacked from floor to ceiling. Dr. Arrold starting growing these mushroom varieties in jars two years ago, and hasn’t had a holiday since. (fourth) Empty mushroom jars are sterilised in the autoclave between crops, so that disease doesn’t build up. (bottom) The clean jars are filled with sterilised substrate using a Japanese-designed machine, before being inoculated with spawn]. [Image: Temperature map of the London Underground system (via the

[Image: Temperature map of the London Underground system (via the  [Image: A very amateur bit of Photoshop work: Li-Sun Mushrooms as packaged for Australian supermarket chain

[Image: A very amateur bit of Photoshop work: Li-Sun Mushrooms as packaged for Australian supermarket chain

[Images: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel].

[Images: Shiitake logs on racks in the Mittagong mushroom tunnel]. [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Ebenezer Howard’s original scheme for the

[Image: Ebenezer Howard’s original scheme for the  [Image: A lemon grown in Dulwich; photograph by Jonathan Gales (2008), ©

[Image: A lemon grown in Dulwich; photograph by Jonathan Gales (2008), © [Image: From Mikey Tomkins’s series of

[Image: From Mikey Tomkins’s series of  [Image: The water selection at

[Image: The water selection at  [Image: The

[Image: The