[Image: Australia’s Great Barrier Reef].

[Image: Australia’s Great Barrier Reef].

A “vanished giant has reappeared in the rocks of Europe,” New Scientist writes. It extends “from southern Spain to eastern Romania, making it one of the largest living structures ever to have existed on Earth.”

This “bioengineering marvel” is actually a fossil reef, and it has resurfaced in “a vast area of central and southern Spain, southwest Germany, central Poland, southeastern France, Switzerland and as far as eastern Romania, near the Black Sea. Despite the scale of this buried structure, until recently researchers knew surprisingly little about it. Individual workers had seen only glimpses of reef structures that formed parts of the whole complex. They viewed each area separately rather than putting them together to make one huge structure.”

[Image: The reefs of Raiatea and Tahaa in the South Pacific; NASA/LiveScience].

[Image: The reefs of Raiatea and Tahaa in the South Pacific; NASA/LiveScience].

In fact, Marine Matters, an online journal based in the Queen Charlotte Islands, thinks the reef was even larger: “Remnants of the reef can be found from Russia all the way to Spain and Portugal. Portions have even been found in Newfoundland. They were part of a giant reef system, 7,000km long and up to 60 meters thick which was the largest living structure ever created.”

[Image: The Pearl and Hermes Atoll, NW Hawaii, via NOAA Ocean Explorer].

[Image: The Pearl and Hermes Atoll, NW Hawaii, via NOAA Ocean Explorer].

The reef’s history, according to New Scientist:

About 200 million years ago the sea level rose throughout the world. A huge ocean known as the Tethys Seaway expanded to reach almost around the globe at the Equator. Its warm, shallow waters enhanced the deposition of widespread lime muds and sands which made a stable foundation for the sponges and other inhabitants of the reef. The sponge reef began to grow in the Late Jurassic period, between 170 and 150 million years ago, and its several phases were dominated by siliceous sponges.

Rigid with glass “created by using silica dissolved in the water,” this proto-reef “continued to expand across the seafloor for between 5 and 10 million years until it occupied most of the wide sea shelf that extended over central Europe.”

Thus, today, in the foundations of European geography, you see the remains of a huge, living creature that, according to H.P. Lovecraft, is not yet dead.

Wait, what—

“We do not know,” New Scientist says, “whether the demise of this fossil sponge reef was caused by an environmental change to shallower waters, or from the competition for growing space with corals. What we do know is that such a structure never appeared again in the history of the Earth.” (You can read more here).

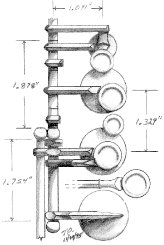

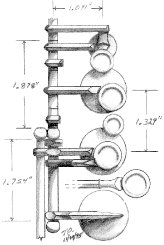

For a variety of reasons, meanwhile, this story reminds me of a concert by Japanese sound artist Akio Suzuki that I attended in London back in 2002 at the School of Oriental and African Studies. That night, Suzuki played a variety of instruments, including the amazing “Analapos,” which he’d constructed himself, and a number of small stone flutes, or iwabue.

The amazing thing about those flutes was that they were literally just rocks, hollowed out by natural erosion; Suzuki had simply picked them up from the Japanese beach years before. If I remember right, one of them was even from Denmark. He chose the stones based on their natural acoustic properties: he could attain the right resonance, hit the right notes, and so, we might say, their musical playability was really a by-product of geology and landscape design. An accident of erosion—as if rocks everywhere might be hiding musical instruments. Or musical instruments, disguised as rocks.

[Image: Saxophone valve diagram by Thomas Ohme].

[Image: Saxophone valve diagram by Thomas Ohme].

But I mention these two things together because the idea that there might be a similar stone flute—albeit one the size and shape of a vast fossilized reef, stretching from Portugal to southern Russia—is an incredible thing to contemplate. In other words, locked into the rocks of Europe is the largest musical instrument ever made: awaiting a million more years of wind and rain, or even war, to carve that reef into a flute, a flute the size of a continent, a buried saxophone made of fossilized glass, pocketed with caves and indentations, reflecting the black light of uncountable eclipses until the earth gives out.

Weird European land animals, evolving fifty eons from now, will notice it first: a strange whistling on the edges of the wind whenever storms blow up from Africa. Mediterranean rains wash more dust and soil to the sea, exposing more reef, and the sounds get louder. The reef looms larger. Its structure like vertebrae, or hollow backbones, frames valleys, rims horizons, carries any and all sounds above silence through the reef’s reverberating latticework of small wormholes and caves. Musically equivalent to a hundred thousand flutes per square-mile, embedded into bedrock.

[Image: Sheridan Flute Company].

[Image: Sheridan Flute Company].

Soon the reef generates its own weather, forming storms where there had only been breezes before; it echoes with the sound of itself from one end to the next. It wakes up animals, howling.

For the last two or three breeding groups of humans still around, there’s an odd familiarity to some of the reef-flute’s sounds, as if every two years a certain storm comes through, playing the reef to the tune of… something they can’t quite remember.

[Image: Sheridan Flute Company].

[Image: Sheridan Flute Company].

It’s rumored amidst these dying, malnourished tribes that if you whisper a secret into the reef it will echo there forever; that a man can be hundreds of miles away when the secret comes through, passing ridge to ridge on Saharan gales.

And then there’s just the reef, half-buried by desert, whispering to itself on windless days—till it erodes into a fine black dust, lost beneath dunes, and its million years of musicalized weather go silent forever.

[Image: Australia’s

[Image: Australia’s  [Image: The reefs of Raiatea and Tahaa in the South Pacific;

[Image: The reefs of Raiatea and Tahaa in the South Pacific;  [Image: The Pearl and Hermes Atoll, NW Hawaii, via

[Image: The Pearl and Hermes Atoll, NW Hawaii, via  [Image: Saxophone valve diagram by

[Image: Saxophone valve diagram by  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image: