[Image: (Right) Ed Mazria, photographed by Doug Hoeschler for Metropolis].

[Image: (Right) Ed Mazria, photographed by Doug Hoeschler for Metropolis].

Last year, Ed Mazria and his New Mexico-based non-profit organization, Architecture 2030, revealed that architecture – or the building sector, more generally – is the largest single source of greenhouse gas emissions, worldwide.

To help prevent “catastrophic” climate change, then, the building sector must become carbon neutral. Reaching that state before the year 2030 is what Mazria has dubbed the 2030 Challenge.

In an effort to speed things along, Mazria will be co-hosting an event, on February 20th, called the 2010 Imperative. This will be a “global emergency teach-in” broadcast live on the web from New York City. The 2010 Imperative – discussed in more detail, below – has been specifically organized around the idea that “ecological literacy [must] become a central tenet of design education,” and that “a major transformation of the academic design community must begin today.”

I recently spoke to Mazria about climate change, sustainable design, and carbon neutrality; about the present state, and future direction, of architectural education; about suburban development, Wal-Mart, and SUVs; and about the 2030 Challenge itself.

What follows is an edited transcript of our conversation.

BLDGBLOG: First, how did you choose the specific targets of the 2030 Challenge?

Ed Mazria: Well, let’s see. The way we developed the 2030 Challenge was by working backward from the greenhouse gas emissions reductions that scientists were telling us we needed to reach by 2050. Working backwards from those reductions, and looking at, specifically, the building sector – which is responsible for about half of all emissions – you can see what we need to do today. You can see the targets that we need to reach so we can avoid hitting what the scientists have called catastrophic climate change.

If you do that, you see that we need an immediate, 50% reduction in fossil fuel, greenhouse gas-emitting energy in all new building construction. And since we renovate about as much as we build new, we need a 50% reduction in renovation, as well. If you then increase that reduction by 10% every five years – so that by 2030 all new buildings use no greenhouse gas-emitting fossil fuel energy to operate – then you reach a state that’s called carbon neutral. And you get there by 2030. That way we meet the targets that climate scientists have set out for us.

That’s how we came up with the 2030 Challenge – meaning a 50% reduction today, and going to carbon neutral by 2030.

[Image: A chart of Architecture 2030’s goals; via Metropolis. Graphic also available as a PDF].

[Image: A chart of Architecture 2030’s goals; via Metropolis. Graphic also available as a PDF].

BLDGBLOG: When you say that the building sector is responsible for half of all greenhouse gas emissions, though, do you mean that in a direct or an indirect sense? Because surely houses aren’t just sitting there emitting carbon dioxide all day – it’s the power plants that those houses are connected to.

Mazria: It’s direct. The number is actually 48% of total US energy consumption that can be attributed to the building sector, most of which – 40% of total consumption – can be attributed just to building operations. That’s heating, lighting, cooling, and hot water. There are others – running pumps and things like that. But 40% of total US energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions can be attributed just to building operations.

BLDGBLOG: What’s the other 8%?

Mazria: The other 8% is greenhouse gas emissions released in producing the materials for buildings – materials that architects can specify – as well as during the construction process itself.

But the major part, you see – 40% – is design. Every time we design a building, we set up its energy consumption pattern and its greenhouse gas emissions pattern for the next 50-100 years. That’s why the building sector and the architecture sector is so critical. It takes a long time to turn over – whereas the transportation sector, on wheels, in this country, turns over once every twelve years.

[Image: “U.S. Energy Consumption by Sector. A reorganization of existing data – combining the energy required to run residential, commercial, and industrial buildings along with the embodied energy of industry-produced materials like carpet, tile, and hardware – exposes architecture as the hidden polluter.” Graphic by Criswell Lappin, via Metropolis].

[Image: “U.S. Energy Consumption by Sector. A reorganization of existing data – combining the energy required to run residential, commercial, and industrial buildings along with the embodied energy of industry-produced materials like carpet, tile, and hardware – exposes architecture as the hidden polluter.” Graphic by Criswell Lappin, via Metropolis].

BLDGBLOG: Speaking of which, you’ve pointed out elsewhere that SUVs only represent about 3% of total greenhouse gas emissions in the US – yet they receive the brunt of the media’s attention and anger. The real culprit is wastefully designed architecture.

Mazria: People must remember, though, that this doesn’t let the US automobile industry off the hook! Cars and SUVs are still part of the problem – and we need to attack that part of the problem.

And there are solutions. One of the solutions, for example, is to use plug-in hybrid flex-fuel technology. Plug-in meaning you can collect energy on your rooftop, with photovoltaic cells, and then plug your car into a battery at night, and drive 30-50 miles on a charge. Then you can use hybrid technology to get incredible miles. Then you can use flex-fuel: you put high-cellulose alcohol or ethanol into the tank, rather than fossil fuels. So there are solutions in that sector.

BLDGBLOG: It seems like the 2030 Challenge has met with a lot of enthusiasm from both the American Institute of Architects and the US Conference of Mayors. Is that the case, or were you hoping for a better response?

Mazria: The response was immediate, and very gratifying. Right when we issued the challenge, in January of 2006, the American Institute of Architects adopted it for all its 78,000 members. That did two things. One, it got the wheels turning within the architecture and building sector to figure out how to meet the Challenge. Two, it began getting resources and information to architects and to designers about how to change course.

Just as important, the US Conference of Mayors then adopted the 2030 Challenge in a resolution that was passed at their annual convention. That was passed unanimously. The Challenge was adopted for all buildings in all cities. That’s very important.

[Image: The interior of Ed Mazria’s New Mexico home, designed by Mazria’s own firm; photographed by Doug Hoeschler for Metropolis. “Masonry walls and floors in the dining and living areas absorb heat and provide cool interior surfaces in summer and warmth in the winter,” we read].

[Image: The interior of Ed Mazria’s New Mexico home, designed by Mazria’s own firm; photographed by Doug Hoeschler for Metropolis. “Masonry walls and floors in the dining and living areas absorb heat and provide cool interior surfaces in summer and warmth in the winter,” we read].

BLDGBLOG: As far as implementing the Challenge goes, is that as simple as sending out a new pamphlet to housing contractors that explains how they can change their building techniques? Or is it as complex as starting whole new university degrees?

Mazria: Well, first you have to inform. People really have to be aware of this issue. Universities don’t really understand their role in this whole situation. So the first step is to inform – and we’ve actually gone a long way in that. We’ve done a lot of magazine articles and other publications; we’ve done public speaking; and there’s also our website – so we’re making an impact.

What we’re really doing is changing the conversation. Through changing – or expanding – the conversation, we’ve been able to issue the 2030 Challenge. We would not have been able to issue that had we not changed the conversation. So we issued the Challenge, which was picked up by the profession and then by the cities, and that was absolutely critical.

Now businesses are picking it up. For instance, at the same time that we were issuing the Challenge, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development came out with a call for carbon neutral buildings by 2050. So we’ve asked the AIA to begin a dialogue with them to get that done by 2030, instead.

Also, since that time, I gave a talk at a conference hosted by the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives. ICLEI‘s membership consists of about 475 cities worldwide. It’s kind of a global counterpart to the US Conference of Mayors – though many cities in the US are members. At the end of that conference, they adopted the 2030 Challenge. They’re now bringing it up with their global Board of Directors, to discuss adopting the Challenge worldwide. Actually, adopted is not the right word – they incorporated the Challenge into their targets.

BLDGBLOG: Do you think the speed with which the Challenge has been adopted reflects a kind of embarrassment over the failure of the Kyoto Protocol?

Mazria: That’s possible. It’s also now more accepted that the science is firm; people are accepting that the debate is essentially over, and that we must move from debate to action. But scientists have given us a very, very small window of opportunity here. We have essentially ten years to begin to get this situation under control. Otherwise we’ll hit tipping points beyond which there will be very little anyone can do to influence things. So there’s a new sense of urgency.

What has been lacking so far are specifics on how to attack the problem. Most initiatives are general, without real teeth behind them, saying that we’re going to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by this much, by this date. But I think that the people who have adopted these initiatives are now looking for ways to implement them, to meet their own targets.

The 2030 Challenge gives them a very specific way to do this – and I think that’s the main reason why this has taken hold as quickly as it has.

BLDGBLOG: In the meantime, you’ve seen corporations like Wal-Mart try to reinvent themselves as pro-green, pro-sustainability firms, because they’ve seen that there is a profit motive. It makes sense for the environment – but it also makes sense for shareholders. The shift isn’t necessarily altruistic.

Mazria: I think it’s going mainstream for a number of reasons. One of the reasons is what we just talked about: the urgency of the issue. There are many people out there with a conscience, and they think about the future rather than just their own immediate needs. They think about their children and their grandchildren. I think that’s moving some of this.

But I think you’re right: I think another part of this is essentially self-serving, that going green may give you a leg up on the competition. It may save you money. It may enhance your image in the community, which means your business can maneuver with more ease and fewer restrictions.

The real point is: whatever the motivation, it’s going in the right direction.

[Image: Skylit gymnasium in Genoveva Chavez Community Center, Santa Fe; designed by Mazria Inc. Photo by Robert Reck, via Metropolis].

[Image: Skylit gymnasium in Genoveva Chavez Community Center, Santa Fe; designed by Mazria Inc. Photo by Robert Reck, via Metropolis].

BLDGBLOG: So what roles do the architecture and design schools play in all this?

Mazria: An AIA COTE report came out last year, called Ecology and Design. It was a year-plus long study by a panel of AIA COTE members. Every school should read this.

From page 43: “Schools and teachers are discovering and creating new ways to incorporate sustainability into studios and other coursework. There appears to be more out there than there was 5 or 10 years ago and the efforts are deeper, more layered, and more complex.” But this next part is what’s important: “But our sample includes not a single example where the issues have informed a true transformation of the core curriculum. As promising as many of the courses are, it must be said that sustainable design remains a fringe activity in the schools.”

It gets worse:

Many of the most highly rated architecture schools show little interest in sustainable design, according to our research. The Ivy League schools, which consistently draw top applicants, have not made a noticeable effort to incorporate environmental strategies into their coursework. With few exceptions – notably California Polytechnic State University-San Luis Obispo, our top winner – the same may be said of all the programs listed in the 2005 Design Intelligence ranking of top schools. The implication is that ecology is not considered a design agenda but, rather, an ethical or technical concern. If the best programs, instructors, and students do not embrace ecology as an inspiration for good design, what chance does this endeavor have to transform the industry?

Now I want to turn to Cal Poly-San Luis Obispo, their “top winner.” This is Cal Poly: “the most significant drawback of the Sustainable Environments program is the fact that it is an elective minor and not an integral part of the core curriculum. Though enrollment in program grows every year, currently only about 20 percent of CAED students take part.” Now, listen to this: “Dean Jones, who is new to the school, sees the Sustainable Environments minor as a pilot program for the entire department: ‘It is a long-term goal to integrate this kind of approach within the core curriculum.'” Long-term.

You have ten years basically to change course across the entire building sector, and the top-ranking ecological design program has a sustainable development minor. The top school. And it’s a long-term goal for them. So you get the picture.

School’s must transform – and they must transform immediately. So we’ve organized what we term the 2010 Imperative. That will explain to all the schools what we think needs to be done today, immediately, as well as beginning with the next school year – and, to complete the process, what needs to be done by 2010.

By 2010 we’re looking at total ecological literacy in architectural education.

BLDGBLOG: The 2010 Imperative is a “global emergency teach-in” scheduled to occur in about three weeks’ time. Could you tell me a little bit more about that?

BLDGBLOG: The 2010 Imperative is a “global emergency teach-in” scheduled to occur in about three weeks’ time. Could you tell me a little bit more about that?

Mazria: The teach-in will happen on February 20th. It will be a live webcast from the New York Academy of Sciences, from 12-noon to 3:30. It will have four speakers: Dr. James Hansen of NASA will talk about the science and the implications of global warming, and the urgency for action. I’ll talk about the building sector and what we need to do – and why – and how education is a critical piece of this whole thing. Susan Szenasy will do the introductions, and talk about all the design disciplines. She’ll also moderate the panel at the end. And Chris Luebkeman will give a talk called “Doing Is Believing” – which is pretty interesting – and he’ll talk about Arup‘s projects all over the world. That should take about an hour and a half.

Then it will be open to questions and answers – and general discussion – from people typing-in, live, from anywhere in the world. So it’s as participatory as we can get. We’ll also have a live audience of about 300-plus, made up of people from the nine New York City-area design schools.

BLDGBLOG: Have universities and institutions outside of New York signed up to participate?

Mazria: The teach-in has been supported by the ACSA, the AIA Committee on the Environment, the US Green Building Council, and a lot of other schools. We’ve received emails now – probably about 15,000 – from people saying that they’re going to log on. We’ve got schools that are going to be canceling classes that day and creating full-day events around the teach-in – so it’s very exciting. We’re getting responses from everywhere: Berkeley, Harvard, Cal-Poly-San Luis Obispo, UW-Milwaukee. 50 to 100 come in a day, including practitioners and architecture offices that are going to get their whole office to participate. Those offices will also get continuing education credits for their architects.

You know, you can give a lecture to 1000 people, or to 500 people, or to 300 people – but this way you’re talking to tens of thousands of people, in one day. It’s a really good way to use the technology to get the word out.

BLDGBLOG: Some of these changes are going to require a pretty major conceptual shift, I think. You’re moving from an artistic or historical approach to architecture – where architecture is something of an expressive design medium – and you’re going to an approach that treats the built environment as something whose effect is scientifically measurable. Ecologically speaking, a design can literally be good or bad, no matter what it looks like, or whether or not the client likes it. Do you see this as a possible issue down the road?

Mazria: I think you can incorporate both personal expression and aesthetics into ecological literacy. Ecological literacy just gives you another tool with which to design. Architecture is not just pure sculpture; it’s not just pure function; it’s not just pure performance – it’s all of those. And so what must be added and integrated into the design curriculum is this notion of ecological literacy. You cannot design anymore without being literate in this area – otherwise you’re doing more harm than good.

BLDGBLOG: Beyond the teach-in, how do you anticipate getting this message into the schools and design offices? Is this a question of issuing textbooks and PDFs, or just organizing more events?

Mazria: You’re not going to do it one school at a time. There are too many schools. You have hundreds of thousands of students being educated today, and they are not fully ecologically literate. They don’t have a total grasp of the global situation we’re facing, and what must happen next. And it’s not just the students – their instructors aren’t fully aware of this, either.

So we propose to do this in two ways. One is an immediate method, and one is a short-term method. The immediate method is well-defined: we will address every design school in the world, globally, and we will ask every instructor to add one sentence to every problem that they issue in their design studios. That’s all we’re asking them to do. We’re not asking them to change the assignments – we’re asking them to add one sentence.

That sentence is: “That the project be designed to engage the environment in a way that dramatically reduces or eliminates the need for fossil fuels.”

This will set off a chain reaction, globally, throughout the student population. Because what the students will do at the outset of a new assignment is they will research the issue. They’ll then come back to the class with all the information they can find – and all the information, by the way, is available on the internet. They have access very, very quickly to this information. They’ll then bring everyone else in that class, including the instructor, up to speed on the issues, the design strategies, and the technologies that are available and part of the design palette. Out of that, universities and professional studios will become instruments for transforming design.

If you bring creative problem-solving to the issue, many, many different ways of addressing the problem will come about – in ways we can’t even imagine. And that’s the beauty of making this change immediately.

We can then work on a systematic approach, between 2007 and 2010, to bring true ecological literacy to all the design schools.

[Image: Materials Testing Facility, Vancouver, designed by Busby Perkins + Will. The design “incorporates recycled and reused materials extensively throughout the building,” and other “sustainable (‘green’) building design concepts, such as natural ventilation and solar shading have also been utilized.” Via Architecture 2030].

[Image: Materials Testing Facility, Vancouver, designed by Busby Perkins + Will. The design “incorporates recycled and reused materials extensively throughout the building,” and other “sustainable (‘green’) building design concepts, such as natural ventilation and solar shading have also been utilized.” Via Architecture 2030].

BLDGBLOG: In that same time period, do you plan to approach large-scale home developers, like Toll Brothers or KB Home, to inspire environmental change on a larger and more immediate scale?

Mazria: You have to remember that we’re a very small organization! [laughs] I think, though, that a growing movement around these issues, and around the 2030 Challenge, is beginning to take shape, so I would imagine that there are many other people in other industries who may begin to embrace these changes. For example, there’s an organization called ConSol, and they address the mass-market housing industry in terms of the issues we just talked about. There’s the Urban Land Institute. There’s the Congress for the New Urbanism. They all specifically address how such issues affect development.

BLDGBLOG: What about designing a kind of prototype development, or model village, that might serve to exemplify the 2030 Challenge?

Mazria: To teach by design? I think that’s happening. On our website, we have a whole section on projects that begin to meet the targets, and we do have buildings that fit that category, that we’ve designed over the years. In fact, in the 1980s, we designed the Mt. Airy Library that reduced its consumption of fossil fuels over an average building of that type, in that region, by over 80%. Just through design.

In fact, in the early 1980s, right after the first energy crisis, the US Department of Energy sponsored anywhere between twelve and eighteen architects around the country to design very low-energy buildings. I would say probably every one of those architects demonstrated that you could get reductions of 50-80% just through design! There were many, many buildings built in the late 1970s, and during the 1980s, using passive solar design, and day-lighting principles, that actually put those buildings off the grid.

So you have a wealth of information generated way back then. It wasn’t until oil went down to $10 a barrel, and the Reagan Administration came in and basically killed off all these initiatives, that we really came to rely on fossil fuels. Now our buildings are sealed up; they have no real integrated relationship with the exterior environment. When we talk about a connection to the environment in architecture today, for the past 30 or 50 years we’ve just been talking about a visual connection. We haven’t been talking about a real, integrated, energy-based connection between the building and its environment. And that’s where the term open systems comes from – and where we need to be headed.

[Image: School of Nursing and Student Community Center, Houston, designed by BNIM. From their website: “Goals of increased air quality, increased natural daylighting, reduction of polluting emissions and run-off, and increased user satisfaction and productivity were achieved using the LEED® rating system.” Via Architecture 2030].

[Image: School of Nursing and Student Community Center, Houston, designed by BNIM. From their website: “Goals of increased air quality, increased natural daylighting, reduction of polluting emissions and run-off, and increased user satisfaction and productivity were achieved using the LEED® rating system.” Via Architecture 2030].

BLDGBLOG: If you drew up actual plans for a carbon neutral city of the future, though, wouldn’t that give people a clearer sense of what all this will look like? Which would then help both the clients and the architects understand what they need to do next?

Mazria: I think that’s a really good question – because having some imagery for what we’re talking about is very important in terms of us acting. But for only one person to come up with a plan or an image – that might actually do more damage than good. I think you need a whole range of aesthetics and ideas to take shape, and what shakes out will be those ideas and solutions that work. I think tying it to just one visual image would not be helpful.

BLDGBLOG: You’ve also talked about the importance of new design software – software that can model, in real-time, the projected energy-use of an architectural design. That would help architects meet their emissions targets. Has there been any progress on that front?

Mazria: Every time we make a decision – we reorient the building, we twist it, we add glazing, we use this kind of material, we add a shading device, we reposition or realign a wall – we have to have, in the corner, the energy implications of that. It should be as simple as just two numbers: one would indicate whether we’re meeting our target of a 50% reduction, or a 60% reduction, or a 70% reduction – how close we are to hitting that target. The other would indicate the actual embodied energy in the materials and construction of the building. If we had those two numbers as we design our buildings, then, intuitively, as designers, we would understand the results of our actions.

These design tools are a critical piece, and the major players are AutoDesk, Google – we need them to take this on almost as an emergency effort, to put this on a fast-track. In fact, Green Building Studio is already working diligently in this area. Students can send their design over to them and get an analysis back in, I think, fifteen minutes – for free. But the companies that supply us with these tools really need to step up to the plate. The federal government can help, or the larger states that have resources of money can help, by putting some dollars into R&D and getting those tools out there immediately.

BLDGBLOG: Could you issue a kind of Software Challenge to help kick things into gear?

Mazria: We could. I think that, because the AIA adopted the 2030 Challenge, you would see now that the federal government and the larger states – and the cities, and the companies – would not be far behind. Adopting the Challenge was critical in getting more movement in this area. I think as more cities adopt the Challenge, and want to understand how they can implement it, they’re going to require certain kinds of software, and the software companies will be competing to supply that software.

Right now we’re in the process of creating a huge market for those tools. If the Challenge gets adopted by the schools, then even the schools will be looking for this software.

We’re helping to put a market in place – so the software companies will have to act.

[Image: Energy Savings Buildings, Albuquerque; designed by Mazria Inc. Photo via Metropolis].

[Image: Energy Savings Buildings, Albuquerque; designed by Mazria Inc. Photo via Metropolis].

BLDGBLOG: Finally, you mentioned mayors earlier. How has your experience been with other political leaders, at different levels of government?

Mazria: It’s actually gone quite well – the mayors are highly interested and motivated. I was in Washington yesterday, actually, talking to Senators and to members of Congress about getting federal support. That would mean having federal buildings lead the way – because the federal government does quite a lot of building – probably about 3% of total construction – and we’re asking for all federally-funded buildings to meet the Challenge targets.

We’re also asking for incentives to help meet these targets, until everyone gets up to speed. In some cases there are costs involved, so if you provide incentives you can help accelerate the adoption of the Challenge – so the quicker we get incentives into place, the better.

But there’s now a lot of interest on Capitol Hill for what we’re talking about.

BLDGBLOG: Is that because of the elections this past November?

Mazria: It is.

We just don’t have that much time left. We really have to work absolutely as hard as we can right now to get things done. We need everyone – I mean everyone – really pulling in the same direction, and not getting discouraged. You can make things happen. Everyone has a role in making things happen. I can’t emphasize this enough: we need everyone. It’s the people who respond to the situation that will make it happen – and that’s who we’re looking to reach.

This is doable. It’s a doable job, and I think all the pieces are known; we understand them – we know what needs to be done. We only have to do it now. We now know exactly where we need to be; we know what the reductions are; we know how to get them; we know where to go for the incentives – we just have to make it happen.

The time for small, incremental changes has passed. This is not a top-down action; that’s too slow. This change has to come from across the universities, the industries, and the entire political spectrum.

With huge thanks to Ed Mazria for his interest, efforts, and time. Thanks, as well, to Quilian Riano, for helping set up this discussion.

[Note: This interview was simultaneously posted on both Worldchanging and Inhabitat].

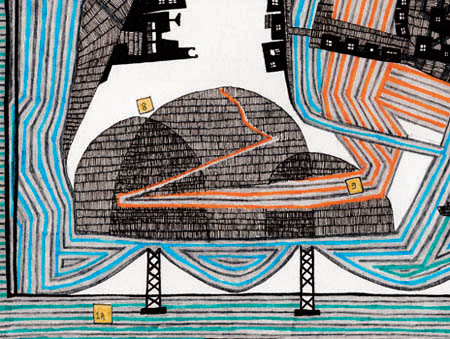

[Image: A remnant glimpse of a lost supercontinent, via the

[Image: A remnant glimpse of a lost supercontinent, via the  [Image: “Chat piles” looming round the “abandoned storefronts and empty lots” of Picher, OK; photo by

[Image: “Chat piles” looming round the “abandoned storefronts and empty lots” of Picher, OK; photo by  [Image: The “Voronoi Shelf” and “Extruded Chair” by Marc Newsom; image by Lamay Photo, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, NYC].

[Image: The “Voronoi Shelf” and “Extruded Chair” by Marc Newsom; image by Lamay Photo, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, NYC]. [Image: A “lathed marble table” by Marc Newsom; image by Lamay Photo, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, NYC].

[Image: A “lathed marble table” by Marc Newsom; image by Lamay Photo, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, NYC].

[Images: Two “extruded” tables by Marc Newsom; image by Lamay Photo, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, NYC].

[Images: Two “extruded” tables by Marc Newsom; image by Lamay Photo, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, NYC]. [Image: Tresor’s new home; photo by Thilo Rückeis for Der Tagesspiegel, via

[Image: Tresor’s new home; photo by Thilo Rückeis for Der Tagesspiegel, via

[Images: The staircase down, and the dancefloor it led to; photos courtesy of

[Images: The staircase down, and the dancefloor it led to; photos courtesy of  [Image: Humans beneath the surface of the earth, listening to music; photo courtesy of

[Image: Humans beneath the surface of the earth, listening to music; photo courtesy of  [Image: The topography of

[Image: The topography of  [Image: Via the

[Image: Via the  For some reason, BLDGBLOG’s recent look at

For some reason, BLDGBLOG’s recent look at  – along with

– along with  [Image: “A white drywall partition, in background at left, separates Simon Taub from Chana Taub in their Brooklyn home.” Via

[Image: “A white drywall partition, in background at left, separates Simon Taub from Chana Taub in their Brooklyn home.” Via  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Excerpt from

[Image: Excerpt from  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via