[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Breaking Out and Breaking In: A Distributed Film Fest of Prison Breaks and Bank Heists—co-sponsored by BLDGBLOG, Filmmaker Magazine, and Studio-X NYC—continued recently with Papillon (1973), directed by Franklin J. Schaffner.

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Papillon remains one of my favorite films, since first seeing it as a teenager (though I will come back to that at the end); however, as usual for this series, I will try to limit myself to the spatial and/or architectural themes of at play in the movie.

In a nutshell, Papillon tells the story of Papillon (played by Steve McQueen), imprisoned in the overseas penal colony of Caribbean French Guiana, on the northeast coast of South America. Papillon alleges that he is and always has been innocent of his charge (killing a pimp in France); nonetheless, France “has disposed of you,” we hear in booming tones from a man with a walrus mustache in the film’s opening scene. “The nation has disposed of you altogether.”

[Images: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Papillon and his fellow prisoners are thus relegated to lives of hard labor, to brutal regimes of solitary confinement, and, in the end, either to forced colonization of French Guiana or to a final stretch of unsupervised years of imprisonment on a craggy island surrounded by sheer cliff walls, the prisoners sent there deemed too broken in body, spirit, and will to pose a risk of escape or violence.

[Images: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Along the way, the carceral gymnastics of the early modern state command the mens’ activities. They arrive at the island on a trans-Atlantic steamer ship, kitted out inside with barred cells and prisoners’ hammocks, its dormitory lined with steam pipes that can be turned on at will to punish the men inside. They are introduced to the guillotine, that disciplinary apparatus of last order of the French state. “Make the best of what we offer you,” an anonymous supervisor says, after the guillotine’s blade has crashed down through a thick stalk of vegetation, demonstrating its raw power, “and you will suffer less than you deserve.”

While on the transport ship, Papillon meets Louis Dega, who has been sent to Guiana for selling counterfeit national defense bonds. “I have no intention of even attempting to escape,” Dega says. “Ever.” He is slightly smiling when he says this, bemusing Papillon, who soon becomes Dega’s paid protection (and long-term friend) in the camps.

However, learning of that friendship, a prison warden whose family lost their fortune in counterfeit defense bounds, sends Papillon and Dega off together to clear swamps with nothing but ropes and their bare hands.

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Their various chores soon include the extraordinary scene of prisoners sent out into the jungle to capture exotic butterflies—an activity that is at least doubly ironic. Not only are captives being asked, in turn, to capture rare species (including one prisoner, Papillon, whose very name comes from the butterfly tattooed on his chest), but, in an awesome detail, we learn that these particular butterflies are valuable precisely because the pigment in their wings is used for inking U.S. currency.

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

That it is Dega who tells us this—the counterfeiter supreme—lends the whole sequence an incredible, if macabre, poetry. But there is also something striking in this revelation of the commodity chain, suggesting that U.S. currency contains the remains of exotic butterflies hunted in the jungle by French prisoners. All objects—even objects that stand for other objects—come from somewhere, including state currency literally printed with the bodies of captives, both human and animal.

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

But, after this point, the real imprisonments—and, of course, the escapes—begin.

Papillon attacks a guard to protect Dega from a routine beating, only to be forced to flee into the jungle—diving into the swamp and swimming off into the roots of mangroves—when he realizes that he’ll be shot on sight for his violation (in fact, he dodges bullets as he leaps into the murky waters).

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Except, of course, he doesn’t make it; he is turned in by local manhunters (former prisoners turned professional trackers of escapees); and he is introduced to the cell in which a great deal of the film then takes place.

A brief note on the architecture of incarceration in Papillon. The cells have bars instead of roofs, allowing them to be watched from above by roving guards. However, this also means that the cell can be “screened”—that is, its only source of light can be blocked for six months at a time, something that soon happens to Papillon (who is reduced to eating roaches and centipedes in the darkness). The prisoners receive their rations through a small hole near the floor, which pops open everyday at the sound of a whistle (there is no speaking allowed in the facility, helpfully painted with the word SILENCE in black letters on the outside walls). And the prisoners must lean forward and stick their heads through holes in the cell door for things like hair cuts and lice treatments—but also for occasional interrogations by the warden and his guards.

[Images: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

While locked up in darkness, Papillon has a dream in which he confronts a makeshift judge and jury on the beach somewhere back in France. For whatever reason, I have always loved this scene. “You know the charge,” a faceless judge shouts at Papillon. “Yours is the most terrible crime a human being can commit. I accuse you of a wasted life… The penalty is death.” Horrified by the accuracy of the charge, Papillon wanders back the way he came, muttering, “Guilty… Guilty… Guilty…”

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

In any case, it wouldn’t be Breaking Out and Breaking In if we didn’t soon see some escapes.

Papillon, Dega, and another prisoner called Maturette make a break for it one night over the camp wall. To make an extremely long story short, they must sail to freedom by way of a leper colony and increasingly rough seas; but, arriving safely in Honduras, they’re forced to split up. Papillon runs into the rain forest with a local prisoner they happen to bump into on the beach, and the two of them are then hunted through the jungle by Afro-Caribbean trackers hired by the state. Many more events transpire—booby traps, cliff jumps, pearl-fishing tribesmen—before Papillon makes his way to a convent in a local town center, seeking refuge and forgiveness. However, the church being, in effect, a wing of the state, mistaking ideological correctness for Christian morality, the nuns turn him in. I mention this also to indicate how, in the film, the state works: it relies upon—indeed, it cannot function without—local yet unofficial representatives, people it can hire (trackers) or who it can trust to volunteer (nuns) in the name of state continuity. In other words, the state puts out a call when a gap or blind spot arises, knowing there will always be someone who answers it.

So Papillon is sent back to solitary confinement.

I’ll just make two final points, while admitting that I’ve hardly grazed the surface of the film.

1) Papillon’s final escape comes from Devil’s Island, the aforementioned island of sheer cliffs where even guards are seen as unnecessary, the prisoners physically and mentally exhausted and thus believed to be incapable of investing in the effort of escape. But Papillon one day notices something in the waters of the bay below, a rhythm in the waves that allows for anything thrown into the water to avoid being crushed on the rocks and, instead, be dragged out to sea.

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

He first experiments with some coconuts—and then, lashing together a makeshift raft, he throws himself into the seventh wave and makes his way to final freedom.

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

2) The movie closes with one of the most dramatically powerful end title sequences I’ve ever seen. To a haunting soundtrack by Jerry Goldsmith, we’re shown shot after shot of the actual penal colony in French Guiana, left abandoned and rotting in the jungle.

[Images: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

In a sense, these end titles anticipate—and, in many ways, put to shame—much of what we now see today under the guise of “ruin porn,” or photographs of decaying architectural structures.

Regardless of the accuracy of the film’s many dramatic enhancements, the ruined buildings of Papillon have the benefit of context: when the film cuts to the roofless cells and overgrown courtyards of this horrible and violent place of exile, the futility of the entire escapade—the tragedy of anyone caught up in the empty colonial machine—becomes both obvious and crushing. It’s as if no one ever escaped from anything, because there was nothing there in the first place; we’re just left with empty and impotent buildings, dissolved in shafts of light.

[Images: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Images: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

By way of a very brief personal anecdote, when I first saw Papillon as a teenager, and the movie came to an end, I realized, stunned, that I had actually seen the ending before.

Back when I was in the 2nd or 3rd grade, Papillon must have been on cable television, scheduled on more than one day for the same early morning time slot, coming to an end just as I got up and prepared to walk to school. There were thus a few days when I turned on the TV only to catch, without knowing what it was and at almost exactly the same moment each time, the film’s final voice-over narrative and these otherworldly shots of a dead prison in the rain forest, like some upstart challenger to Angkor Wat.

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

[Image: From Papillon, courtesy of Warner Brothers].

Ten years later, watching the film all the way through for the first time, I suddenly realized what it was I’d been daydreaming about in elementary school: the end titles of Papillon.

(Breaking Out and Breaking In will continue in two weeks’ time with the films of Breaking In, and, after I get back from a short trip, I will also continue to post about the Breaking Out series, which continues tonight with Rupert Wyatt’s The Escapist. Full schedule available here).

[Image: “Caves for New York” (1942) by Hugh Ferriss].

[Image: “Caves for New York” (1942) by Hugh Ferriss]. [Image: The New Jersey Palisades, via Wikipedia].

[Image: The New Jersey Palisades, via Wikipedia].

[Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Images: From the

[Images: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the

[Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The

[Images: The

[Images: The

[Images: The

[Images: The

[Image: Composite photograph by

[Image: Composite photograph by  [Image: Composite photograph by

[Image: Composite photograph by

[Images: Composite photographs by

[Images: Composite photographs by

[Image: The Chand Baori stepwell, courtesy of

[Image: The Chand Baori stepwell, courtesy of

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)]. [Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)]. [Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods]. [Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Images: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Images: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)]. [Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Images: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Images: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)]. [Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods (with additional design and modeling by Paul Anvar)]. [Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: From Horizon Houses (2000) by Lebbeus Woods].

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

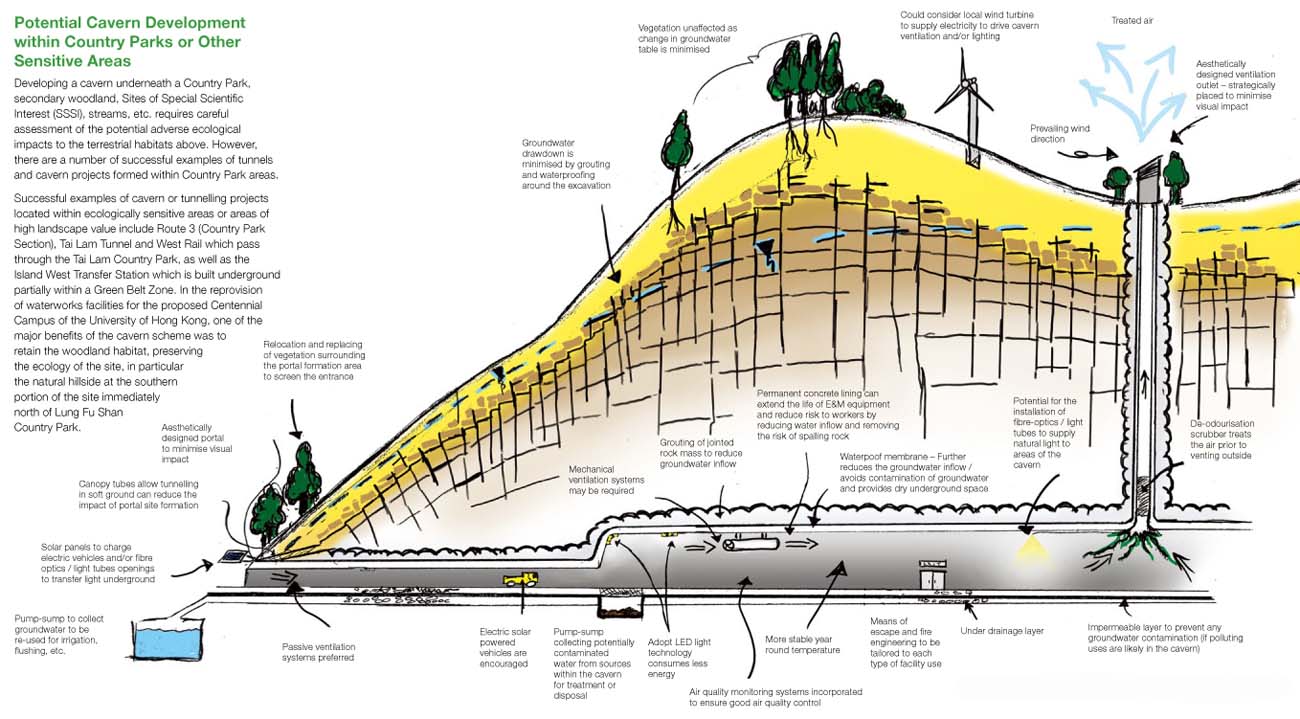

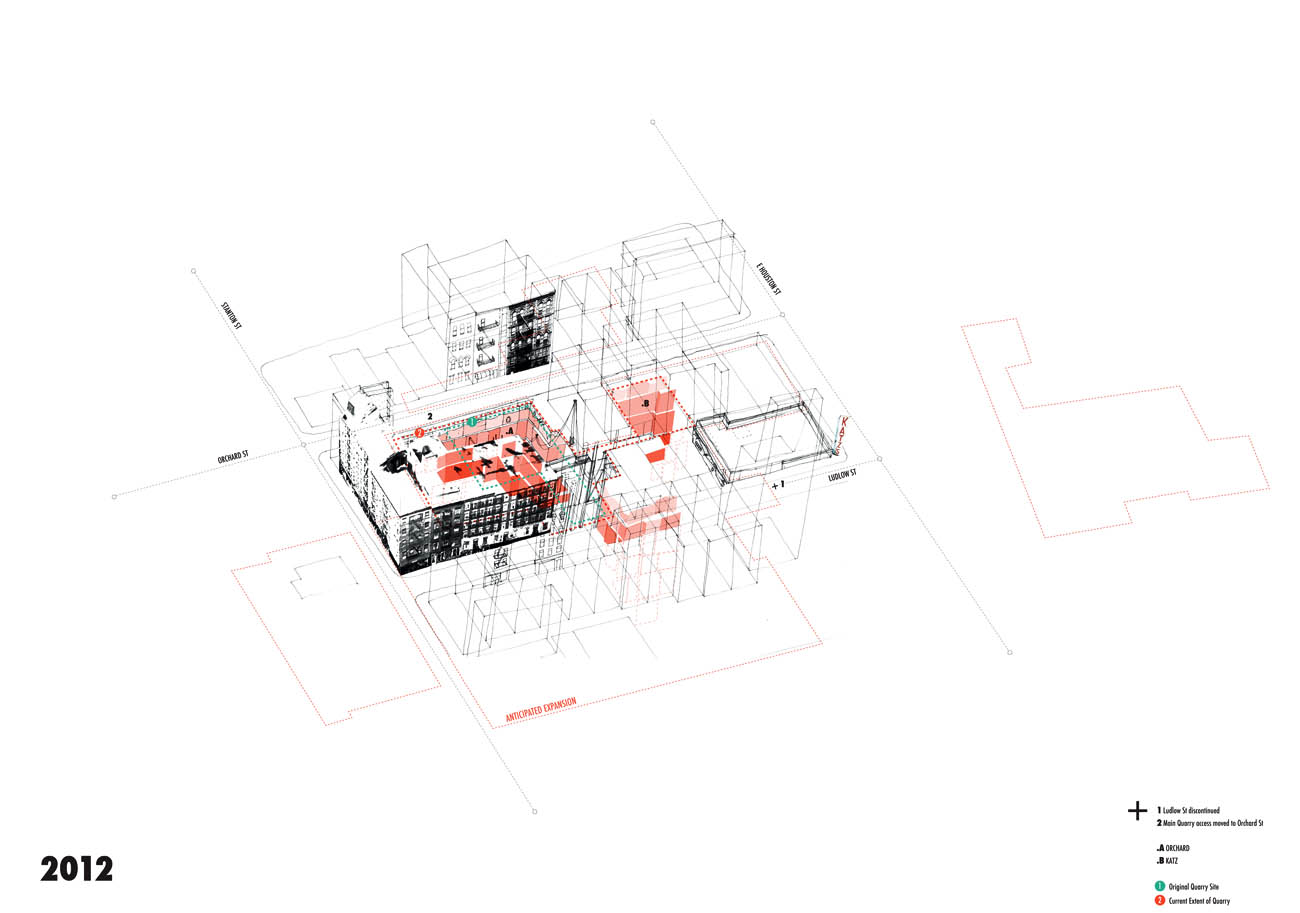

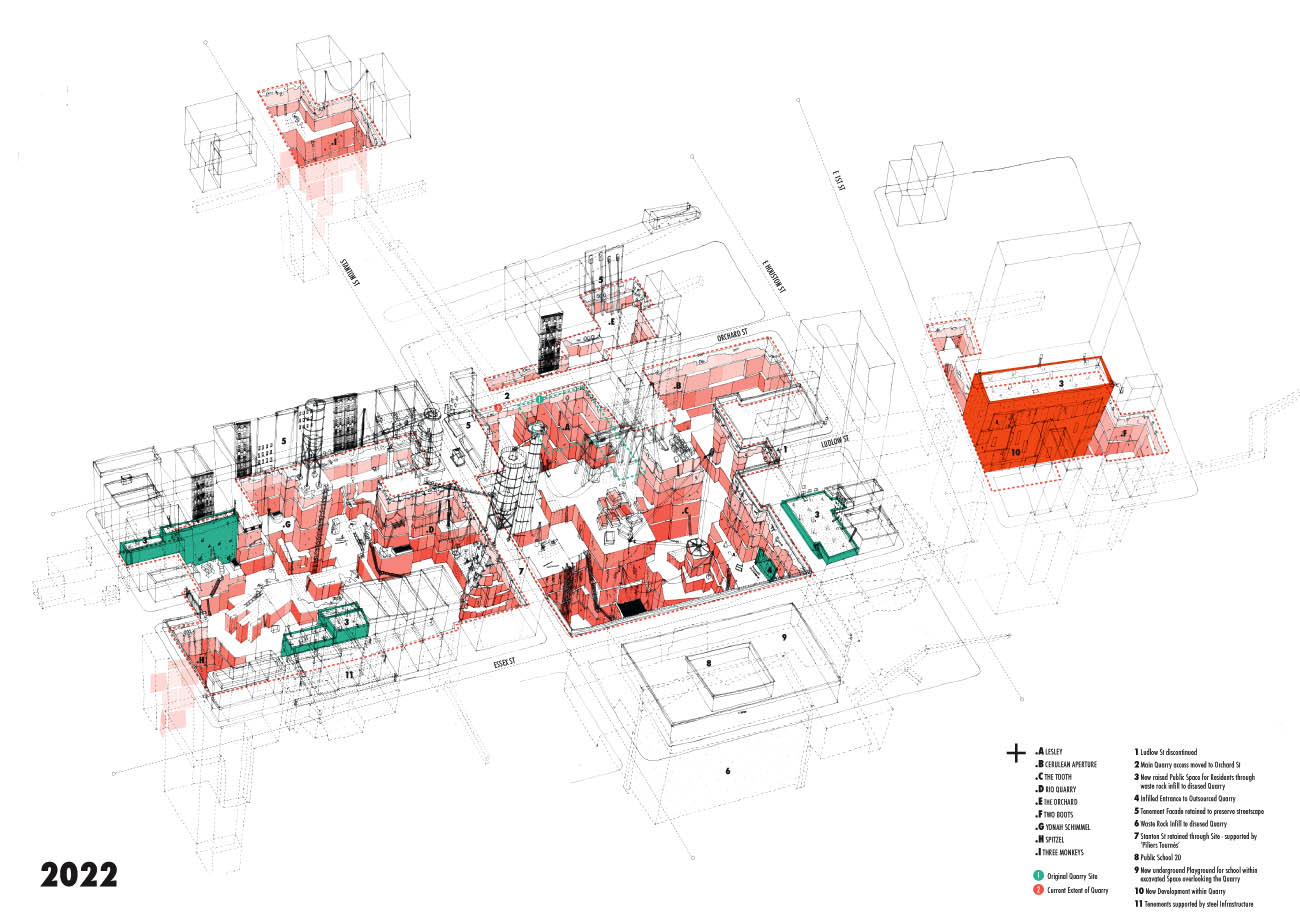

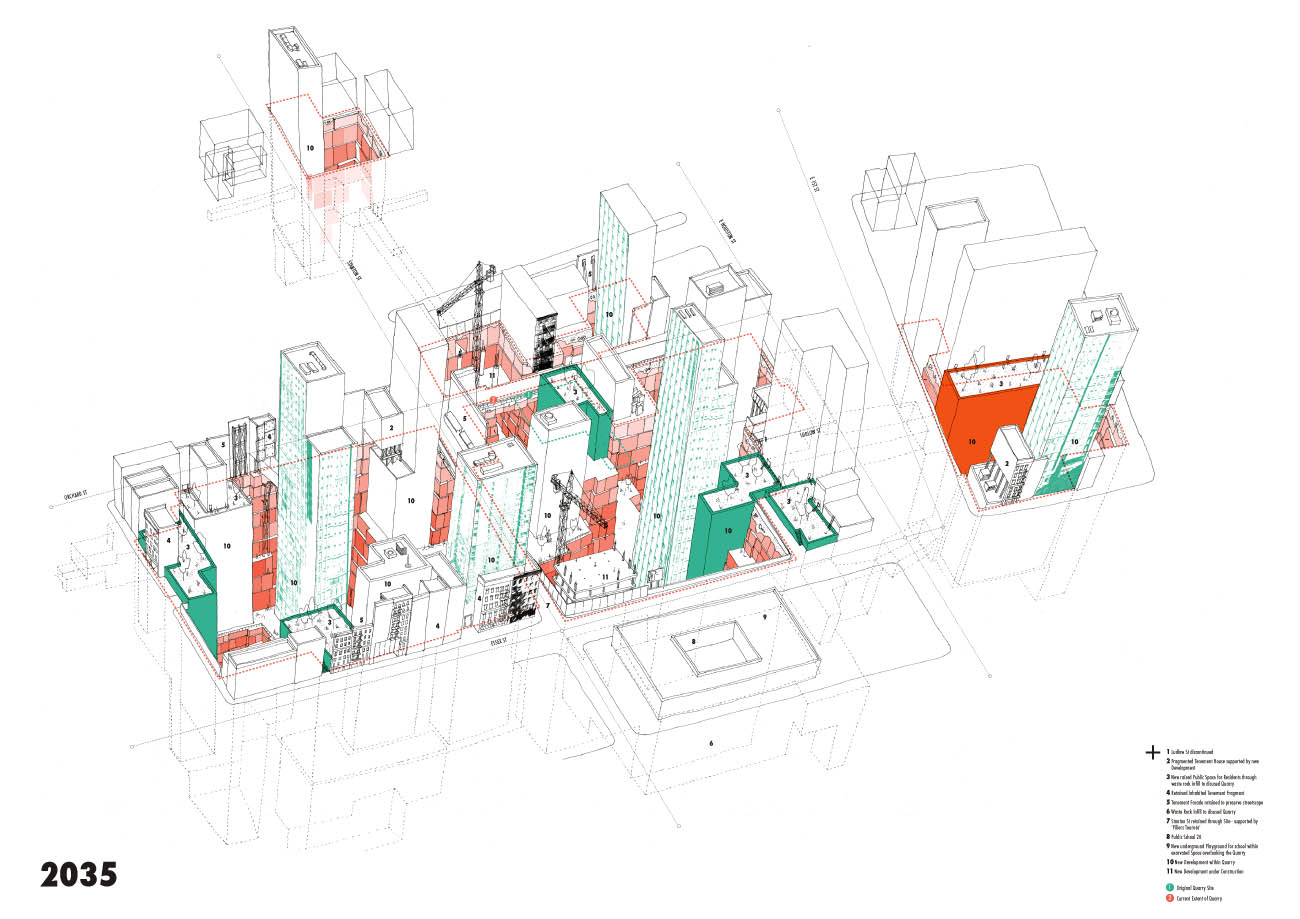

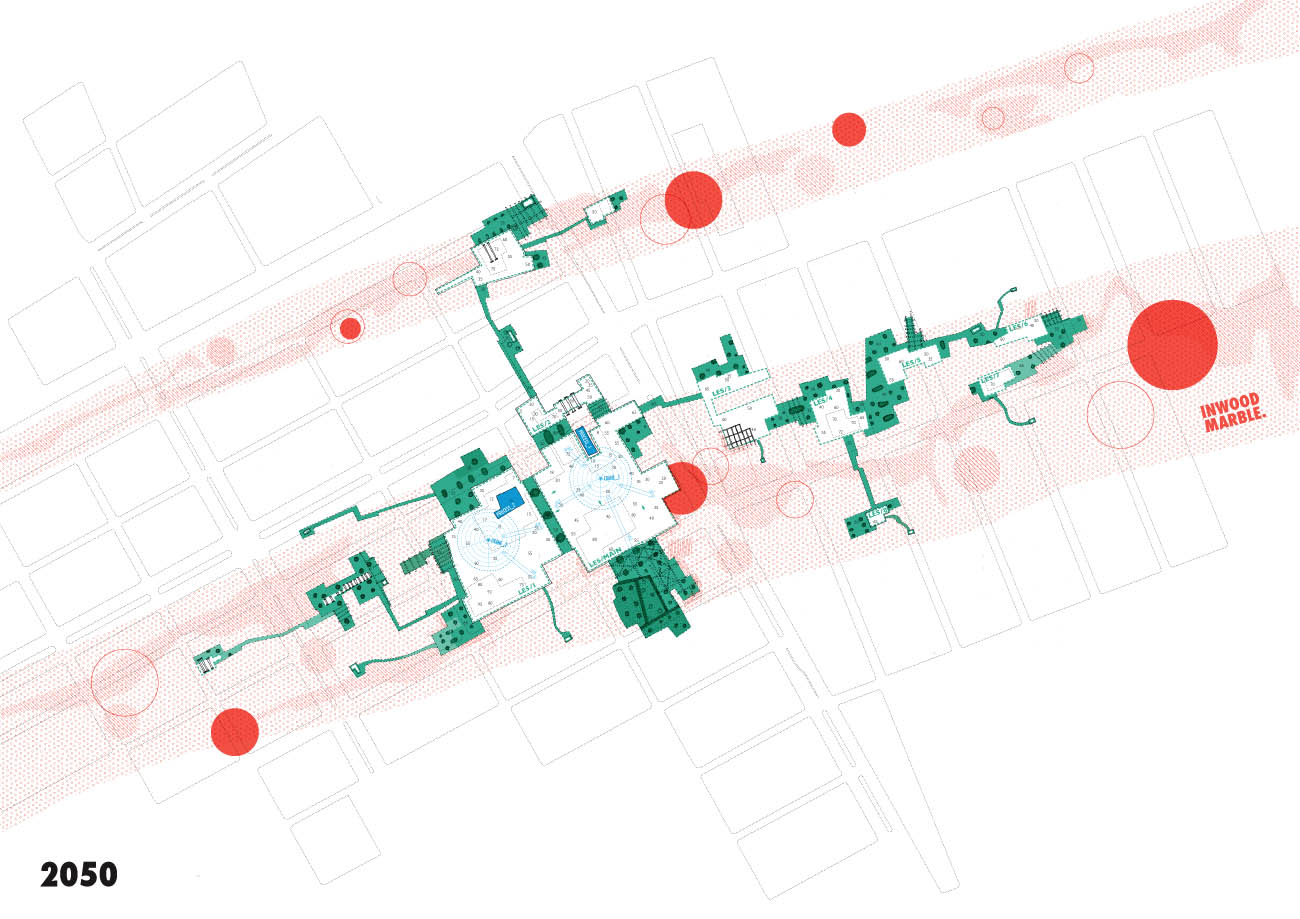

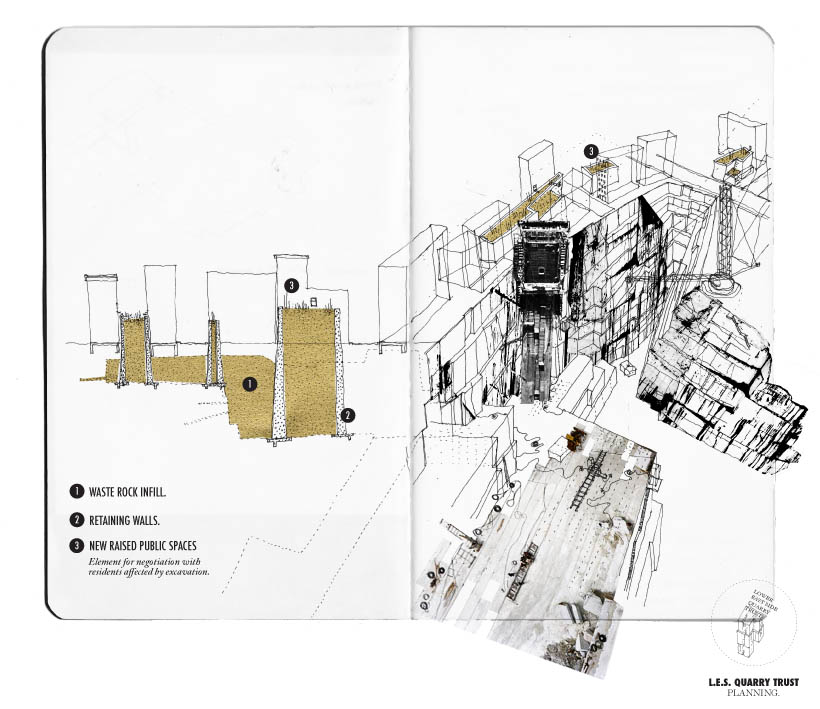

[Image: From “Lower East Side Quarry” by Rebecca Fode; open each image in a new tab for a

[Image: From “Lower East Side Quarry” by Rebecca Fode; open each image in a new tab for a  [Image: From “L.E.S. Quarry” by Rebecca Fode].

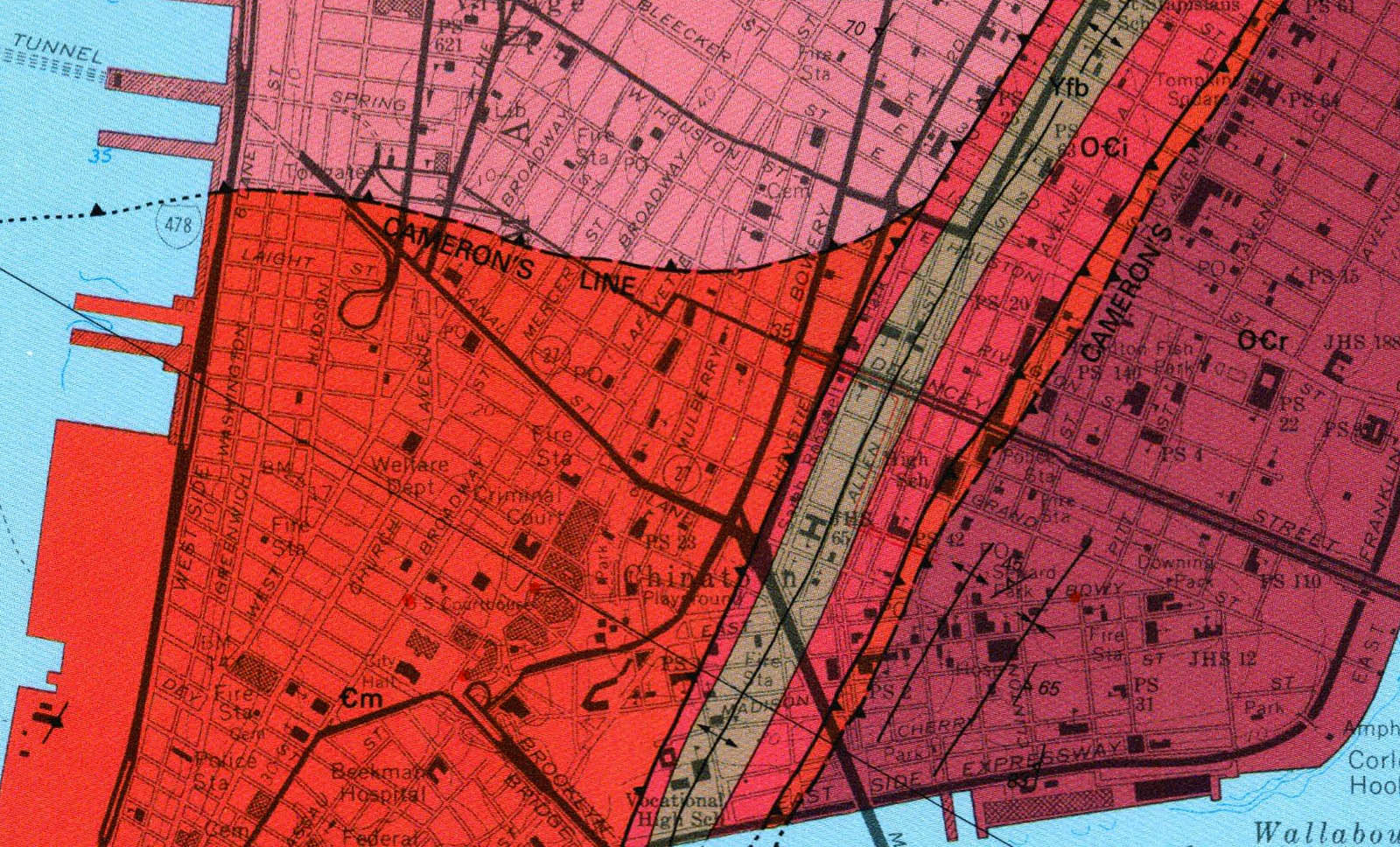

[Image: From “L.E.S. Quarry” by Rebecca Fode]. [Image: Map of Manhattan bedrock, courtesy of the

[Image: Map of Manhattan bedrock, courtesy of the

[Images: From “L.E.S. Quarry” by Rebecca Fode].

[Images: From “L.E.S. Quarry” by Rebecca Fode]. [Image: From “L.E.S. Quarry” by Rebecca Fode].

[Image: From “L.E.S. Quarry” by Rebecca Fode]. [Image: Canada’s

[Image: Canada’s