[Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and Discovery News].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and Discovery News].

I love this story: the polished rock walls of a Catholic church in northern Italy have been found to contain the skull of a dinosaur. “The rock contains what appears to be a horizontal section of a dinosaur’s skull,” paleontologist Andrea Tintori explained to Discovery News. “The image looks like a CT scan, and clearly shows the cranium, the nasal cavities, and numerous teeth.”

The skull itself was hewn in two; “indeed,” we read, “Tintori found a second section of the same skull in another slab nearby.”

[Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and Discovery News].

[Image: Photo courtesy of Andrea Tintori and Discovery News].

The rock itself—called Broccatello—comes from a fossil-rich quarry in southern Switzerland and dates back to the Jurassic. According to the book Fossil Crinoids, “The Broccatello (from brocade) was given its name by stone masons; this flaming, multicoloured ‘marble’ has been used in countless Italian and Swiss baroque and rococo churches”—implying, of course, that other fossil finds are waiting to be found in Alpine baroque churches. “In the quarries of Arzo, southern Switzerland,” the book continues, “crinoids [the fossilized bodies of ancient marine organisms] account for up to half of the bulk of the Broccatello, which is usually a few metres thick.”

In any case, to figure out exactly what kind of dinosaur it is, the rock slab might be removed from the church altogether for 3D imaging in a lab; a new piece of Broccatello rock, mined from southern Switzerland, could be use as its replacement.

The larger idea of discovering something historically new and even terrestrially unexpected in the rocks of a city, or in the walls of the buildings around you—as if the most important fossil site in current geology might someday be the rock walls of a ruined castle and not a cliff face or gorge—brings to mind recent books like Richard Fortey’s fantastic Earth: An Intimate History, with its geological introduction to sites like Central Park, Stories in Stone: Travels Through Urban Geology, and the Geologic City Reports (Parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) by Friends of the Pleistocene. These latter research files present New York City through the lens of its lumpen underpinnings, focusing on bedrock, mineral veins, and salt, not the city’s cultural districts or ethnic history.

But, of course, the H.P. Lovecraftian overtones of this story—a monstrous skull in a church wall—are too obvious not to mention: an easy scenario for imagining whole plots and storylines in which the ancient forms of an unknown species are discovered hidden in cathedral masonry, opening previously unimagined horizons of time and radically revising theories of the history of life on earth.

I just absolutely love the idea that a piece of architecture can become a site for paleontological research, framing an unlikely forensic study of the earth’s biological past.

[Image: A fenced-off, back alley security stair in Toronto, via

[Image: A fenced-off, back alley security stair in Toronto, via  [Image: Oceangoing ships clipped and stitched from Google Maps by artist

[Image: Oceangoing ships clipped and stitched from Google Maps by artist

[Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Barney Peterson, courtesy of the  Just a quick reminder that you have till December 10 to submit to

Just a quick reminder that you have till December 10 to submit to

[Image: A toy antique oscilloscope by Andrew Smith, courtesy of

[Image: A toy antique oscilloscope by Andrew Smith, courtesy of  [Image: An LED cube by

[Image: An LED cube by  [Image: “GPS pigeons” by

[Image: “GPS pigeons” by

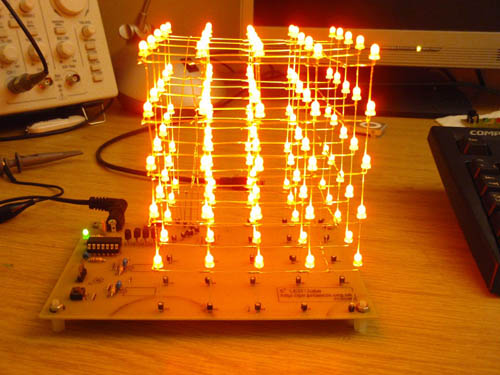

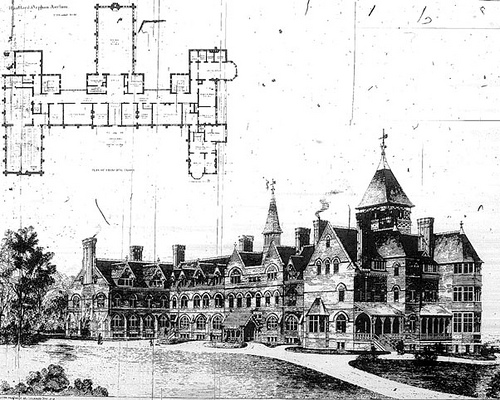

[Image: An old asylum and its floorplan, courtesy of the

[Image: An old asylum and its floorplan, courtesy of the

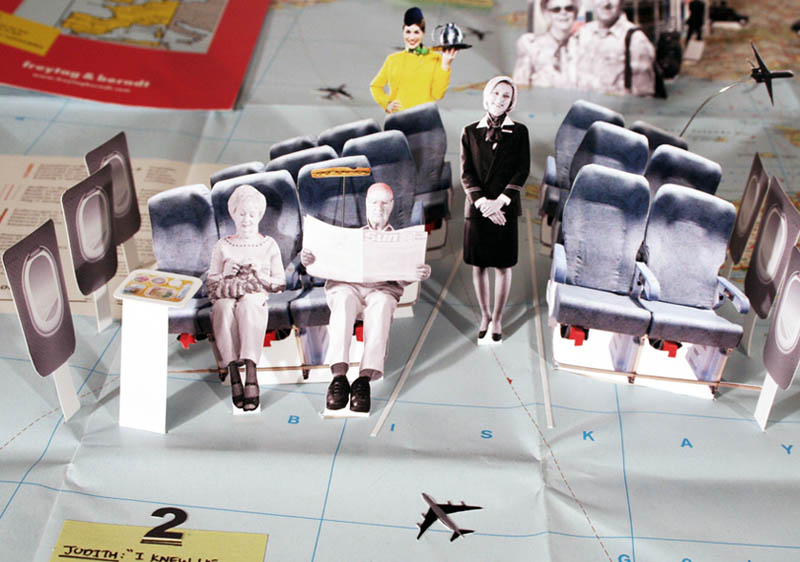

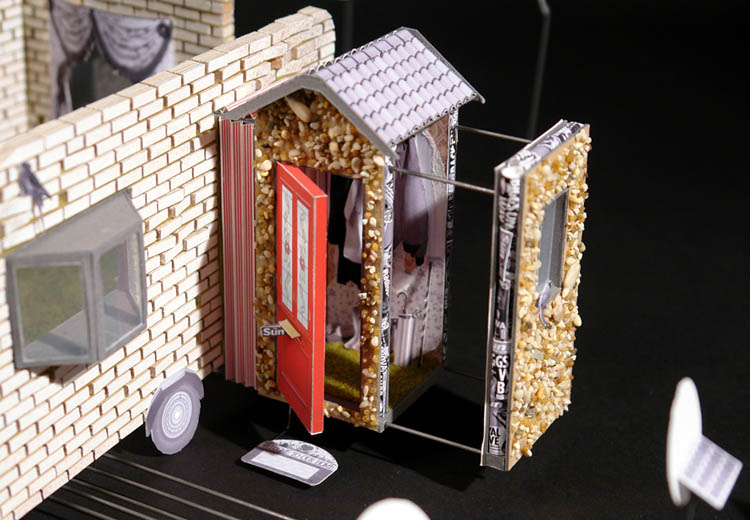

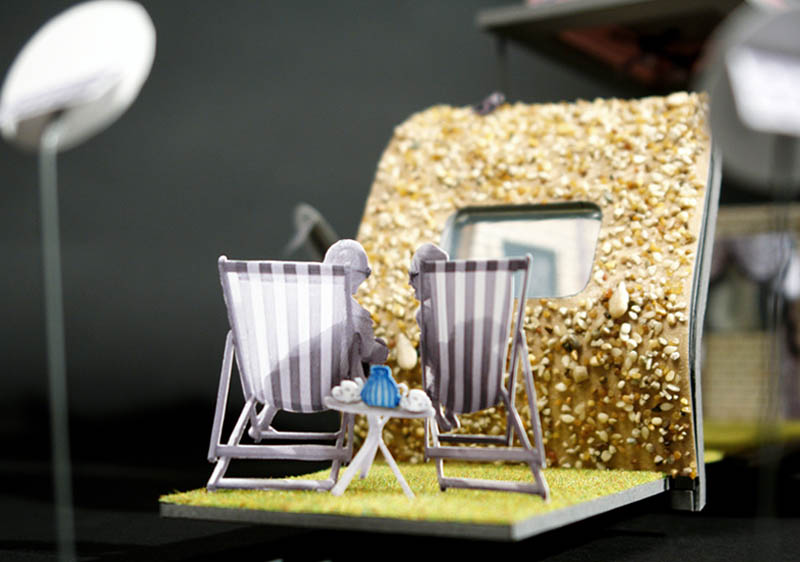

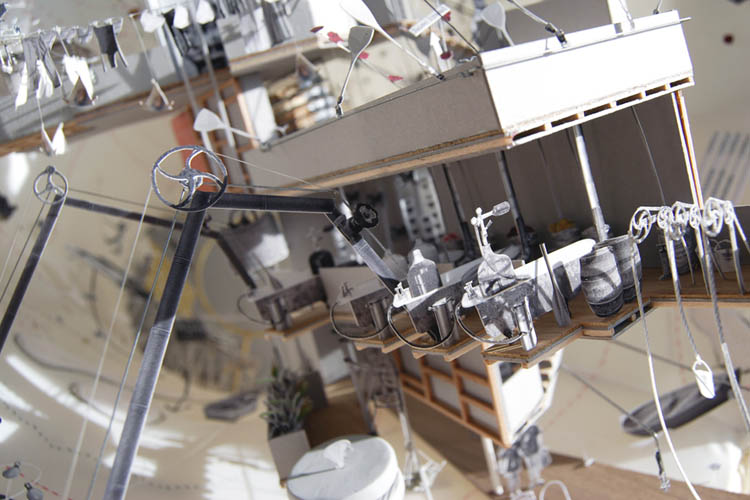

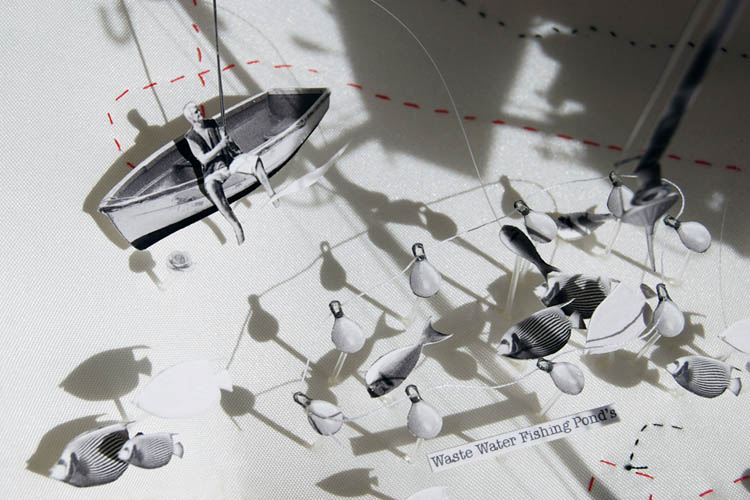

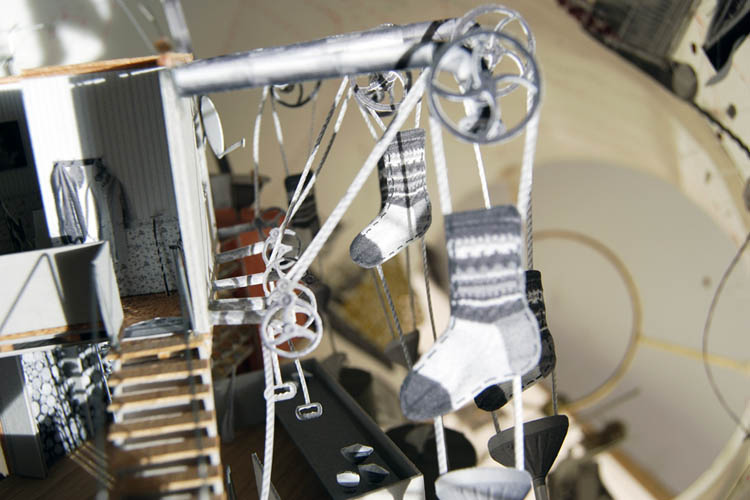

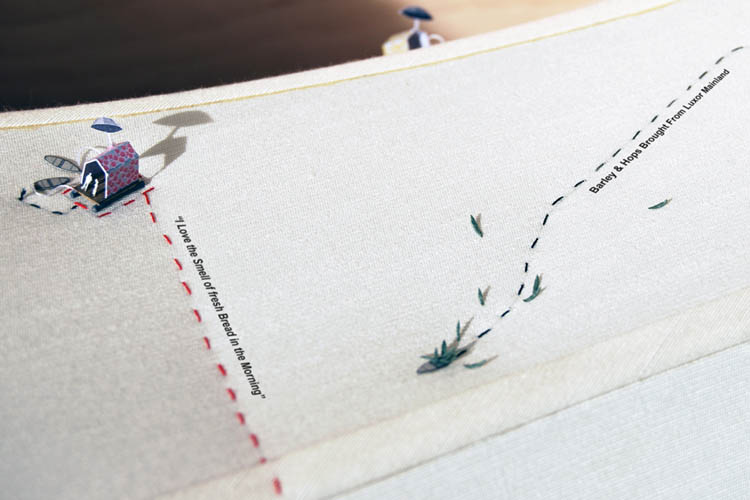

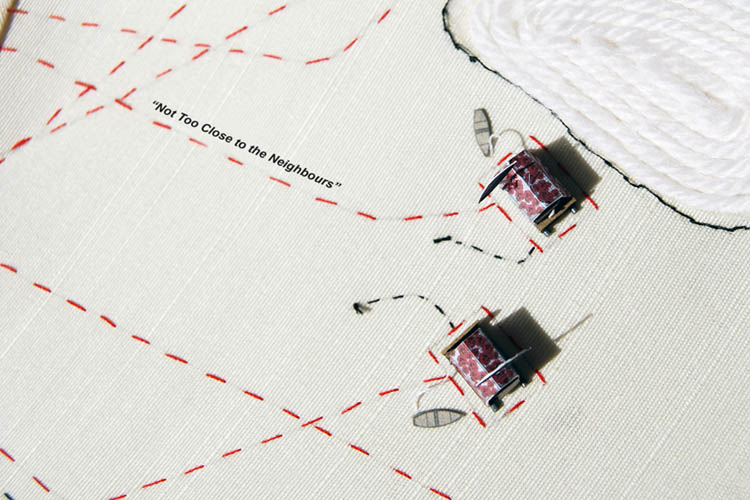

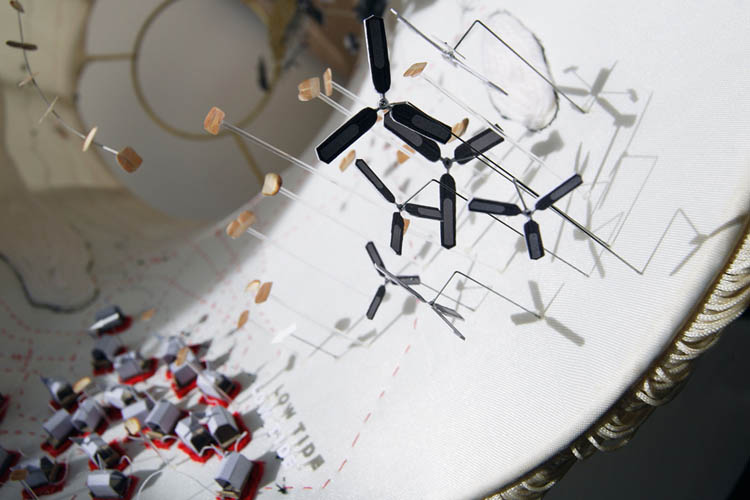

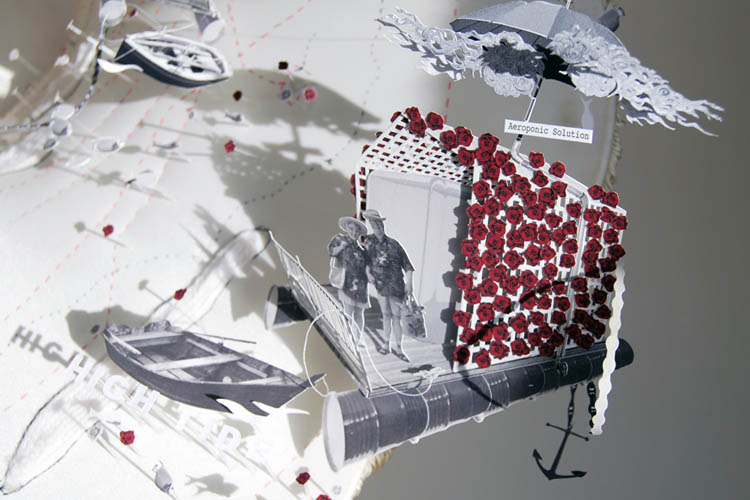

[Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by  [Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Image: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: From “The Migration of Mel and Judith” by

[Images: A “trap street” on Google Maps, documented by

[Images: A “trap street” on Google Maps, documented by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by