[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

The Solitary Life of Cranes is a short film by Eva Weber about the work performed by construction crane operators in London. I’ve mentioned it many times in various talks I’ve given over the past year, but I realized last night that I never actually posted about it—so I thought I’d correct that. It’s a great film, and it’s worth seeking out. At only 27 minutes in length, as well, it’s also quick to watch.

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

As the film describes itself:

Part city symphony, part visual poem, The Solitary Life of Cranes explores the invisible life of a city, its patterns and hidden secrets, seen through the eyes of crane drivers working high above its streets. (…) From their elevated positions, crane drivers are the unsung chroniclers of our ever-changing metropolis: the bulk of their time is spent waiting, looking, observing the wind, the weather, and the people down below. From their airy towers, they do not only have the best overview of the construction site and some of the most impressive panoramic views of the city but also an unparalleled insight into any of the buildings surrounding them.

Looked at one way, Weber has made an oral history of crane operators: documenting where they work, what they think about, what they see, and—perhaps most interestingly—how they view the city.

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

These operators, I would suggest, have a view of the metropolis that architects and planners have little or no access to, an optical insight into city life that often gives their job an almost mystic feel. “Many people don’t know that there’s somebody up there, don’t even think that there’s somebody up there,” one of the operators suggests. “They’re quite surprised when you tell them, ‘yeah there’s a guy up there, you know and this guy is me’.”

There are moments of both inadvertent and advertent voyeurism in the process. “You see really private moments of people’s lives… because people can’t see you or aren’t aware of you.” Indeed, “There’s a couple of people in—how can I put this now without sounding like a voyeur? There are flats right opposite me with the same people in, every day, if you know what I mean, and they’re there, you cannot not look.”

“If you did meet the same person on the street,” one of them says, “then you’d think twice… you wouldn’t introduce yourself, but you stop and think and turn your head when they walk by, you know, as if to say, look I’m part of your life but you don’t know it.”

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber, like a shot from Michael Wolf’s book The Transparent City].

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber, like a shot from Michael Wolf’s book The Transparent City].

One of them even compares the experience to living and working inside a cloud: “Coming down… it’s like coming out of a cloud. You sort of come down it, and it just disappears and then you’re back on normal ground again. You think, ‘Jesus, what a different way of life down here than what it is up there’.”

This terrestrial dislocation is not necessarily a good thing: “We’re getting operators that we all call ‘cab happy’, and they just want to stay on the cab all the time. You know, it’s hard to get them out… I think all crane operators, to a certain degree, I think they’re ‘cab happy’—when you’re on the floor you always miss being in the crane.”

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

One of my favorite moments in the film is when we hear an operator talk about storms. “You can see a storm develop,” he says, looking out over the city, “sort of 10-15 miles away, you can see the cloud shapes, you know, you can watch the rain come in,” and we see moving fronts of English weather cross over the city, “and the rain physically comes in as a wall. You can see that curtain,” he says, “moving across the town, moving across the city.”

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

When I talked about this film at an event in New York City last winter, architect Ed Keller, the event’s host, compared these crane operators to Daedalus figures, looking down into the labyrinth that they themselves have built—only here the labyrinth is London, and the there is not one Daedalus but thousands, and they are awake all the time in overlapping shifts, keeping eyes on the city from above, in perpetuity.

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber; the building in the lower left of this image is actually the London office of Foster and Partners].

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber; the building in the lower left of this image is actually the London office of Foster and Partners].

“The sky is full of stories,” as author Sukhdev Sandhu wrote in an essay for the book A Manual For the 21st Century Art Institution. Looking at the social, economic, and even narrative implicatons of architectural verticality in East London, Sandhu specifically cites Weber’s film:

These men, perched in their metal boxes, invisible to ground-bound Londoners, speak with precision and poetry about the beauty they are afforded by their enhanced perspectives—about the pale delicacy with which the sun rises above the city, the lush greenery of far-off hills, the way streets curve and snake into the distance. They are blessed with the opposite of tunnel vision, able to spot oncoming storms at a distance of fifteen miles, and witnesses to the teeming life that takes place above pavement level: roof-garden parties, office workers taking fag breaks, pigeon fanciers chatting to their birds. London, one of them observes, consists of a series of layers.

Sandhu calls for a need “to gaze out across the callous metropolis—and conjure forth connections,” taking advantage of these unprecedented viewpoints, perspectives on the city that were literally impossible before these buildings and cranes came along, to help fashion a new understanding of how the metropolis works, how people live within it, and where it might yet go. As if the building boom brought with it a new optics of the city—a new picturesque—an angled optometry of everyday space.

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

Briefly, I’m reminded of the story of Babu Sassi, a crane operator atop the Burj Dubai/Burj Khalifa who, the legend goes, didn’t come down to earth for a full year, as it would have taken too long to make the trip. You can read more about Babu at that earlier post, but the overall question would be the same: how does your understanding of the social world change after spending time inside these massive, temporary constructs without names or fixed addresses, as if only unofficially present in the built landscape that surrounds them? They are towers that disappear, never to be seen again in the same location, and you are perched there, like some rogue landscape theorist, at fantastic height above the very thing you both assemble and secretly study.

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

[Image: From The Solitary Life of Cranes by Eva Weber].

More information about the film can be found at its—unfortunately Flash-based—website, and the film itself is worth seeking out.

Every week this autumn, the Glass House Conversations have presented one question, posed by a new host each week, for general discussion online; previous queries have come from designers, writers, architects, critics, and educators, including 2×4, Steven Heller, John Maeda, Alice Twemlow, Alice Rawsthorn, Alissa Walker, and many more.

Every week this autumn, the Glass House Conversations have presented one question, posed by a new host each week, for general discussion online; previous queries have come from designers, writers, architects, critics, and educators, including 2×4, Steven Heller, John Maeda, Alice Twemlow, Alice Rawsthorn, Alissa Walker, and many more.

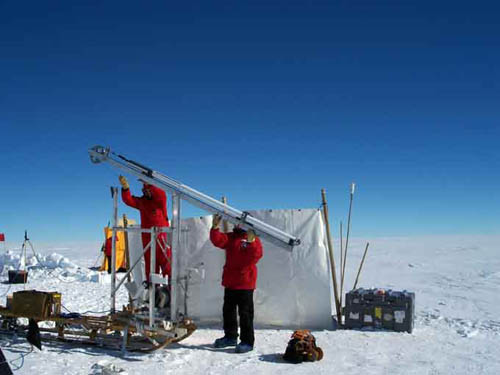

[Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007  [Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007

[Images: From the 2006-2007

[Images: From the 2006-2007  [Image: From the 2006-2007

[Image: From the 2006-2007  I’m thrilled to be kicking off this fall’s

I’m thrilled to be kicking off this fall’s

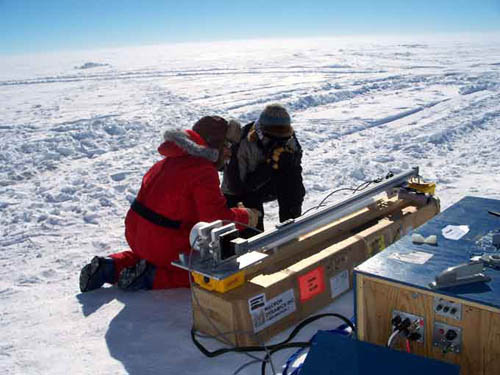

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Images: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Images: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the  [Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the  [Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the  [Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Images: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Images: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the

[Image: From Andrejs Rauchut’s thesis project at the  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

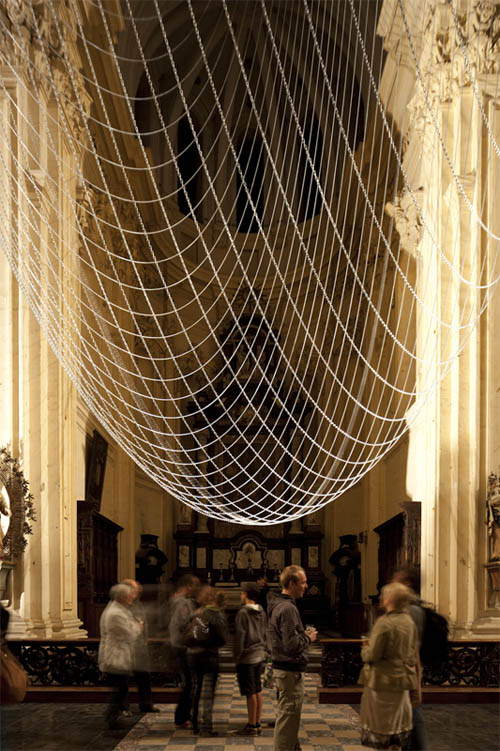

[Image: Proposal image for

[Image: Proposal image for  [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: “

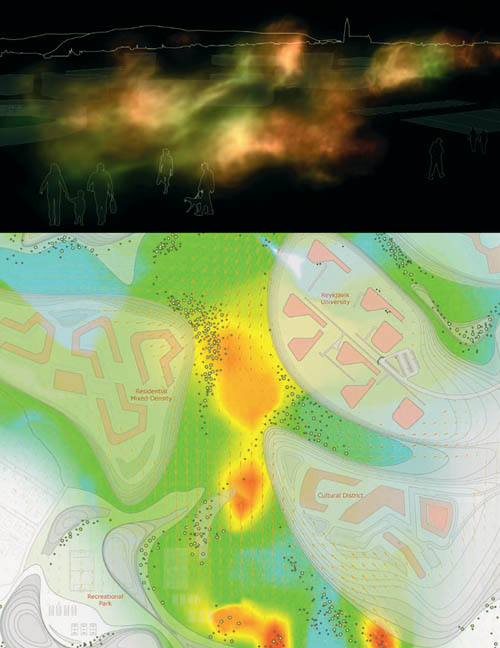

[Image: “ [Image: By Sean Lally, Andrew Corrigan, and Paul Kweton of

[Image: By Sean Lally, Andrew Corrigan, and Paul Kweton of  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: “Santissima Trinidad (Iturgoyen)” by

[Image: “Santissima Trinidad (Iturgoyen)” by

[Images: (top) “Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (Monflorite)” and (bottom) “Nuestra Señora de las Viñas (Quintanilla de las Viñas)” by

[Images: (top) “Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (Monflorite)” and (bottom) “Nuestra Señora de las Viñas (Quintanilla de las Viñas)” by  [Image: “San Juan Bautista (Barbadillo del Mercato)” by

[Image: “San Juan Bautista (Barbadillo del Mercato)” by

[Images: (top) “San Juan de Busa (Larrède),” (middle) “Virgen de Berzosa (Palazuelos de Villadiego),” and (bottom) “Nuestra Señora de las Viñas (Quintanilla de las Viñas)” by

[Images: (top) “San Juan de Busa (Larrède),” (middle) “Virgen de Berzosa (Palazuelos de Villadiego),” and (bottom) “Nuestra Señora de las Viñas (Quintanilla de las Viñas)” by

[Images: (top) “San Vicente (Cervera de Pisuerga),” (middle) “Virgen del Vallejo (Alcozar),” and (bottom) “Virgen del Carmén (Cadalso)” by

[Images: (top) “San Vicente (Cervera de Pisuerga),” (middle) “Virgen del Vallejo (Alcozar),” and (bottom) “Virgen del Carmén (Cadalso)” by  [Image: “San Millan (Velilla de los Ajos)” by

[Image: “San Millan (Velilla de los Ajos)” by  [Image: “San Bartolomé (Ucero)” by

[Image: “San Bartolomé (Ucero)” by

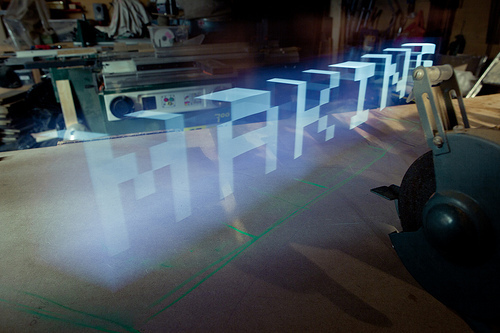

[Images: From Making Future Magic by

[Images: From Making Future Magic by  [Image: From Making Future Magic by

[Image: From Making Future Magic by  [Image: From Making Future Magic by

[Image: From Making Future Magic by  [Image: From Making Future Magic by

[Image: From Making Future Magic by