[Image: A parking meter photographed by shooting brooklyn, via a Creative Commons license].

[Image: A parking meter photographed by shooting brooklyn, via a Creative Commons license].

A story I missed earlier this summer reports that Oakland, California, is making up for falling tax revenue by “aggressively enforcing traffic violations.”

The decision is driven by the city’s budget woes, which deep cuts to city services alone did not solve. Falling sales and property, property transfer and hotel taxes have contributed to a $51 million decline in revenues.

It’s worth asking, though, whether paying “aggressively” increased fees and fines for our everyday use of the city – whether this means road tolls and garbage collection fees or suddenly unaffordable parking meters – is the best financial model for a post-taxation metropolis.

Put another way, if the ongoing recession has revealed, amongst other things, that a new type of city, run along very different financial lines, looms just weeks away – a kind of make-your-own-omelette city of fines, fees, and services, where every ingredient is individually priced – then perhaps the recession might also stimulate a wider debate about what could be called method of payment.

That is, what method of payment do we wish to use when it comes to living in a functioning metropolis? If we find ourselves paying no tax at all, for instance – no income tax, no sales tax, no property tax – would we be happy to pay parking tickets that hit upper limits of, say, $2000 or more each time, if this is what it takes to keep the city running? Conversely, would we be happy to pay more sales tax in order to avoid things like road tolls altogether? How exactly do we mix and match these urban outlays and receipts?

This would seem to cut to some of the most basic questions of what services constitute a city in the first place: what a government might provide and how it is that we will pay for what it offers.

In a distant way, and by means of a long digression, I’m reminded of the oft-repeated idea that nationalized health care would be a mere “hand-out,” not a central platform of what any government might do to protect its citizenry.

For instance, one man at a recent but quite bizarre anti-health care rally – during which a U.S. senator apparently praised this very man for his publicly announced support of terrorism – said that “he could trace his ancestors back to the Mayflower and said ‘they did not arrive holding their hands out for help.'” Ergo, this man should not “hold out his hands for help” and ask the government for a doctor’s visit. Of course, this same argument would surely never be advanced against, say, calling the police, calling the fire department, or accepting the defense of the U.S. military. Yet these are all tax-funded government services.

The bizarre irony for me throughout all of this has been that police officers, fire crews, and members of the military are all, to use this language very deliberately, the most socialized subsector of the U.S. economy. That is, they are paid through what many people would call “government hand-outs.” On the other hand, it is these very social positions that are often held up – by these same critics – as triumphant examples of national service and personal heroism. Indeed, it is not entirely inaccurate to say that The Greatest Generation was a generation of near-total tax-funded employment.

If the recent health care debates are to be believed, doctors are not subject to this same sense of national appreciation; they are mysteriously yet fundamentally unlike the police, we are meant to believe, offering services that only private money can afford. But where is the line between private health (diabetes) and public safety (tuberculosis) – and when might this solidify into actual government infrastructure?

Doctors are not like the tax-funded fire departments who we freely call to save us from wildfires, this logic goes, and they are quite unlike the government-supported soldiers who we have stationed in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. Surely, then, anyone who relies on the U.S. military to protect them is “holding their hands out for help”?

In this context, it’s worth speculating what might happen today if fire departments had, until now, been entirely privatized, motivated to protect you only if your insurance policy was up to date (as, indeed, was the case with the first urban fire departments, and as is now re-emerging in places like California). What would be the reaction, then, if someone proposed that these services be folded into a more general package of government services?

If fire crews, in this model, suddenly became tax-funded and available to all citizens – indeed socialized as part of a shared, city infrastructure – would there be the same level of outrage? One wonders if fire crews might ever attain the entirely deserved levels of public adulation they now receive, if their tax-funded nature was, once and for all, revealed. Protesting citizens, like the gentleman cited above, might never have the stomach to “ask for help” from the government, even if their houses are burning down around them.

In any case, I mention all this because of the urgency with which we need to rethink the world of urban services and the economic basis through which we pay for them. If the tax system, as it is currently operated, cannot pay for the very activities that we once thought synonymous with urbanity, are radical increases in one-off fees a permanent, economically viable solution to this problem or simply an irritating and only mildly effective band-aid? Is it better to pay more, once a year, in order to avoid such fees altogether?

Further, how are we best to judge the effectiveness of increased fines and pay-as-you-go services: by the psychological sense of irritation that a penalty-based system might cause – I’m reminded of parking attendants required to wear bulletproof vests during streetwork – or by the comfort that a lack of taxes might provide?

Or, more measurably, do we judge them by their physical effect on the city?

(Original article spotted via the denialism blog).

[Image: View larger].

[Image: View larger]. [Image: View larger].

[Image: View larger]. [Image:

[Image:

[Images: All photos by

[Images: All photos by  [Image: A parking meter photographed by

[Image: A parking meter photographed by  [Image: “Lightning Bugs in York, PA,” by

[Image: “Lightning Bugs in York, PA,” by  [Image: Bioluminescent billboards on one of the Galapagos Islands, by Octave Perrault].

[Image: Bioluminescent billboards on one of the Galapagos Islands, by Octave Perrault]. [Image: Bioluminescent billboards by

[Image: Bioluminescent billboards by  [Image: A map of the

[Image: A map of the  [Image: A bioluminescent tobacco plant, via

[Image: A bioluminescent tobacco plant, via  [Image: Inside

[Image: Inside  [Image: From

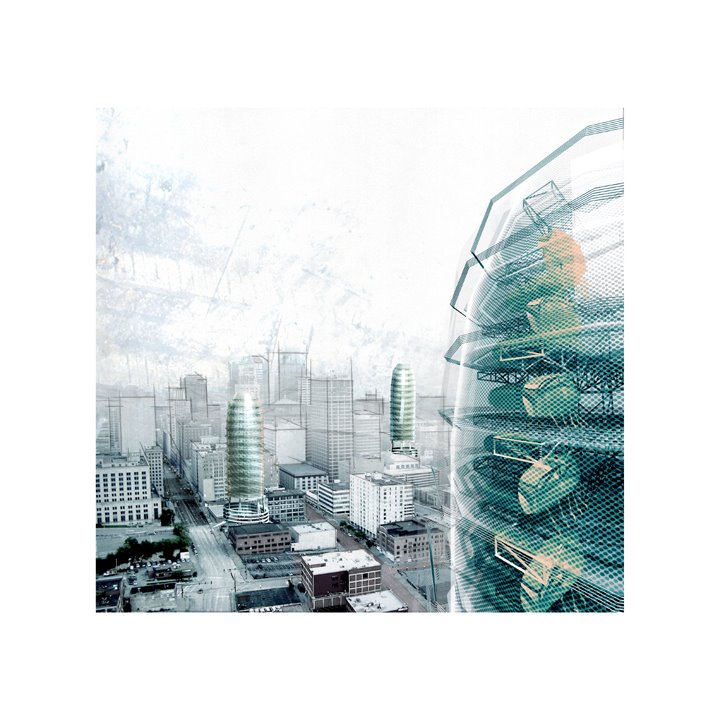

[Image: From  [Image: Unidentified student work from

[Image: Unidentified student work from  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: Six photographs by

[Images: Six photographs by  [Image: “The Garden of Machines” by Nathan Freise, from his extraordinarily well-produced

[Image: “The Garden of Machines” by Nathan Freise, from his extraordinarily well-produced  [Image: “The Garden of Machines (Dwell)” by Nathan Freise, from

[Image: “The Garden of Machines (Dwell)” by Nathan Freise, from  [Image: “Transience (The Nomads)” by Nathan Freise, from

[Image: “Transience (The Nomads)” by Nathan Freise, from  [Images: “Transience (Decay and Renewal)” by Nathan Freise, from

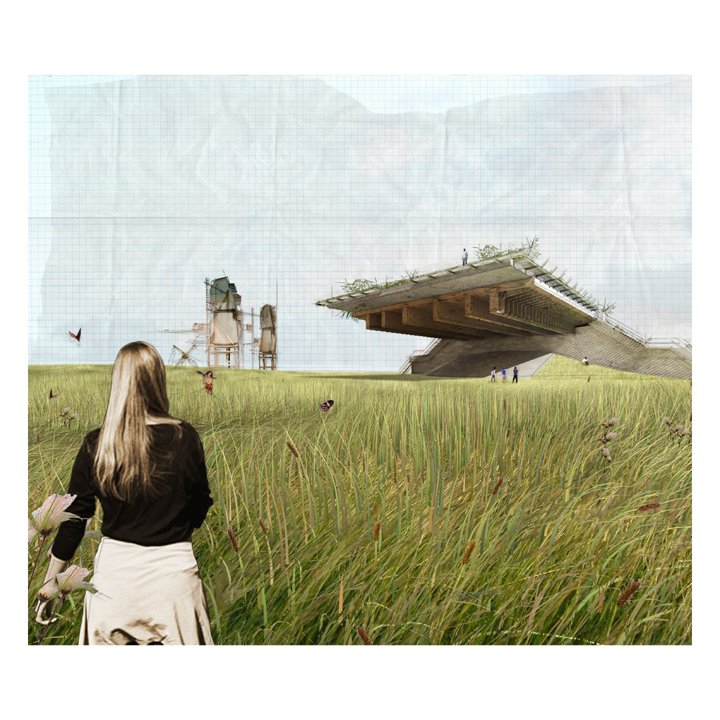

[Images: “Transience (Decay and Renewal)” by Nathan Freise, from  [Image: From Sean Regan’s final project at

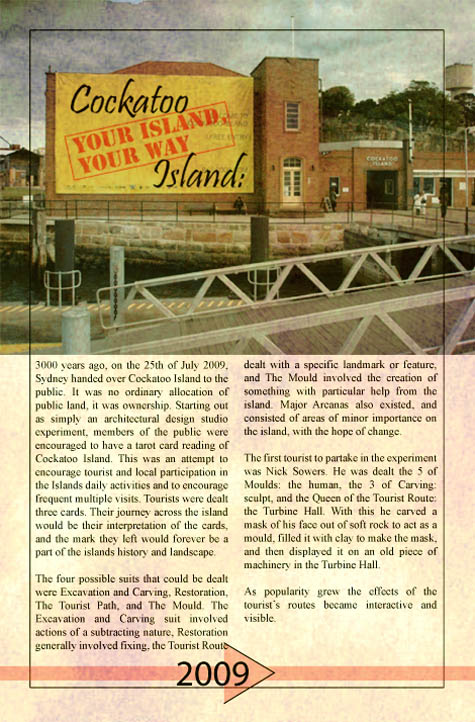

[Image: From Sean Regan’s final project at  [Image: Image and text from Sean Regan’s final project at

[Image: Image and text from Sean Regan’s final project at

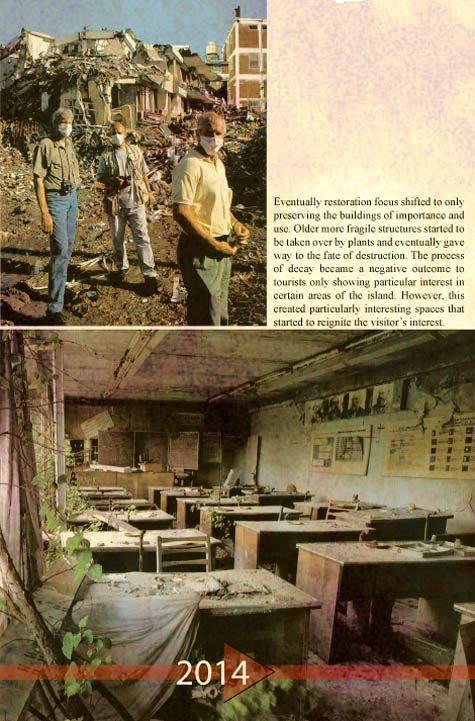

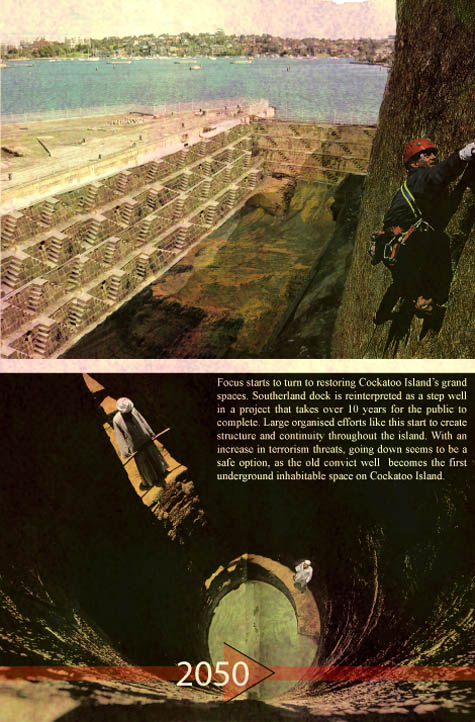

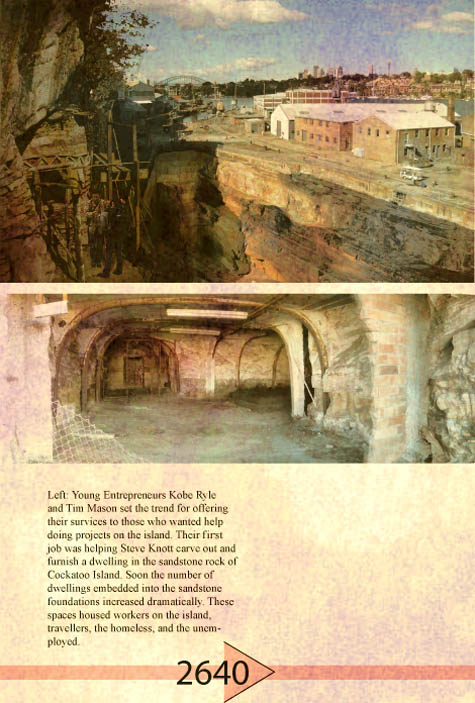

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at

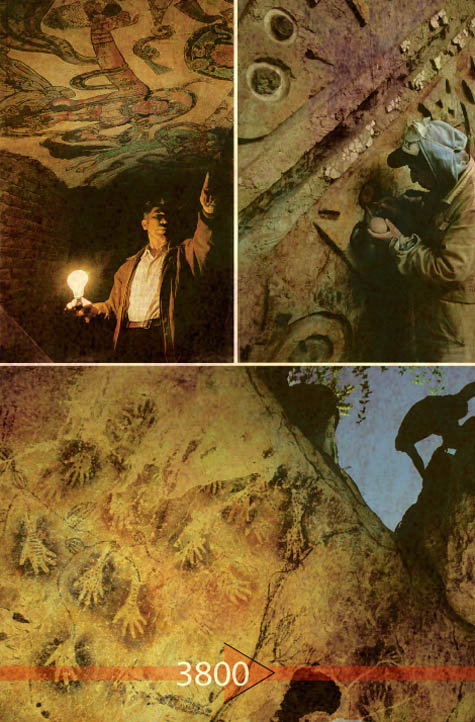

[Images: From Sean Regan’s final project at  [Image: Cockatoo Island is now a warren of artificial caves extending for kilometers into the earth’s surface below. From Sean Regan’s final project at

[Image: Cockatoo Island is now a warren of artificial caves extending for kilometers into the earth’s surface below. From Sean Regan’s final project at