[Image: “Lightning Bugs in York, PA,” by tom.arthur, courtesy of a Creative Commons license].

[Image: “Lightning Bugs in York, PA,” by tom.arthur, courtesy of a Creative Commons license].

While traveling last week, I managed to re-read W.G. Sebald’s book The Rings of Saturn.

At one point, Sebald describes two entrepreneurial scientists from the 19th century, who he names Herrington and Lightbown; together, we’re told, they had wanted to capture the bioluminescent properties of dead herring and use that as a means of artificially illuminating the nighttime streets of Victorian London.

Sebald writes:

An idiosyncrasy peculiar to the herring is that, when dead, it begins to glow; this property, which resembles phosphorescence and is yet altogether different, peaks a few days after death and then ebbs away as the fish decays. For a long time no one could account for this glowing of the lifeless herring, and indeed I believe that it still remains unexplained. Around 1870, when projects for the total illumination of our cities were everywhere afoot, two English scientists with the apt names of Herrington and Lightbown investigated the unusual phenomenon in the hope that the luminous substance exuded by dead herrings would lead to a formula for an organic source of light that had the capacity to regenerate itself. The failure of this eccentric undertaking, as I read some time ago in a history of artificial light, constituted no more than a negligible setback in the relentless conquest of darkness.

Sebald goes on to write, elsewhere in the book, that, “From the earliest times, human civilization has been no more than a strange luminescence growing more intense by the hour, of which no one can say when it will begin to wane and when it will fade away.”

But it’s the idea that we could use the bioluminescent properties of animals as a technique of urban illumination that absolutely fascinates me.

In fact, I’m instantly reminded of at least three things:

1) Last month I had the pleasure of stopping by the Architectural Association’s year-end exhibition of student work. As part of a recent studio taught by Liam Young and Kate Davies, a student named Octave Augustin Marie Perrault illustrated the idea of a “bioluminescent bacterial billboard.”

From the project text: “A bioluminescent bacterial billboard glows across the harbour… We are constantly reminded of the condition of the surrounding environment as the bio indicators becomes an expressive occupiable ecology.”

[Image: Bioluminescent billboards on one of the Galapagos Islands, by Octave Perrault].

[Image: Bioluminescent billboards on one of the Galapagos Islands, by Octave Perrault].

In many ways, Perrault’s billboards would be a bit like the River Glow project by The Living… only it would, in fact, be illuminated by the living. These bioluminescent bacteria would literally be a living window onto a site’s environmental conditions (or, of course, they could simply be used to display ads).

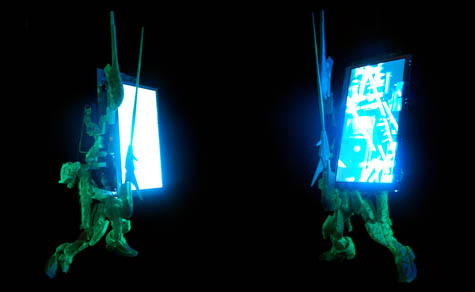

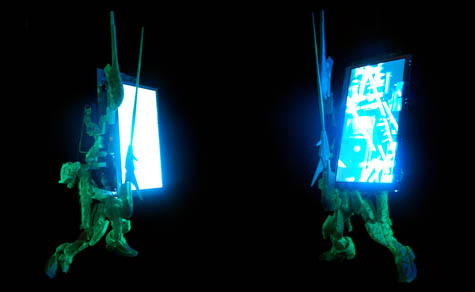

Liam Young, the studio’s instructor, has also designed a version of these bioluminescent displays, casting them more fantastically as little creatures that wander, squirrel-like, throughout the city. They pop up here and there, displaying information on organic screens of light.

[Image: Bioluminescent billboards by Liam Young].

[Image: Bioluminescent billboards by Liam Young].

I’m genuinely stunned, though, by the idea that you might someday walk into Times Square, or through Canary Wharf, and see stock prices ticking past on an LED screen… only to realize that it isn’t an LED screen at all, it is a collection of specially domesticated bioluminescent bacteria. They are switching on and off, displaying financial information.

Or you’re watching a film one night down at the cinema when you realize that there is no light coming through from the projector room behind you – because you are actually looking at bacteria, changing their colors, like living pixels, as they display the film for all to see.

Or: that’s not an iPod screen you’re watching, it’s a petri dish hooked up to YouTube.

This is what I imagine the world of screen displays might look like if Jonathan Ive had first studied microbiology, or if he were someday to team up with eXistenZ-era David Cronenberg and produce a series of home electronic devices.

Our screens are living organisms, we’ll someday say, and the images that we watch are their behavior.

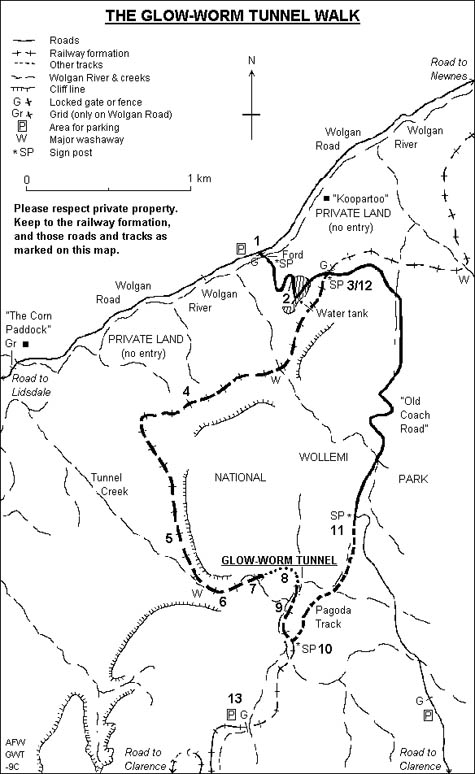

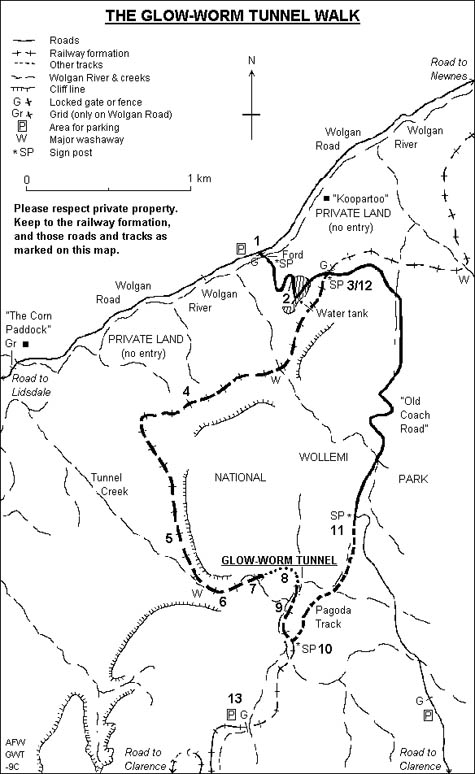

2) As I mentioned in an earlier post, down in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales is a tunnel called the Newnes Glow Worm Tunnel. It is a disused railway tunnel, bored through mountain sandstone 102 years ago, that has since become the home for a colony of glow worms.

As that latter link explains: “If you want to see the glow worms, turn off your torch, keep quiet and wait a few minutes. The larvae will gradually ‘turn on’ their bioluminescence and be visible as tiny spots of light on the damp walls of the tunnel.”

[Image: A map of the Glow Worm Tunnel Walk, New South Wales].

[Image: A map of the Glow Worm Tunnel Walk, New South Wales].

Incorporate this sort of thing into an architectural design, and it’s like something out of the work of Jeff VanderMeer – whose 2006 interview here is still definitely worth a read.

I’m picturing elaborate ballrooms lit from above by chandeliers – in which there are no lightbulbs, only countless tens of thousands of glow worms trapped inside faceted glass bowls, lighting up the faces of people slow-dancing below.

Or suburban houses surviving off-grid, because all of their electrical illumination needs are met by specially bred glow worms. Light factories!

Or, unbeknownst to a small town in rural California, those nearby hills are actually full of caves populated only by glow worms… and when a midsummer earthquake results in a series of cave-ins and sinkholes, they are amazed to see one night that the earth outside is glowing: little windows pierced by seismic activity into caverns of light below.

3) Several years ago in Philadelphia, my wife and I went out for a long evening walk, and we sat down on a bench in Washington Square Park – and everything around us was lit by an almost unbelievable density of fireflies, little spots of moving illumination passing by each other and overlapping over concrete paths, as they weaved in and out of aerial formations between the trees.

But what if a city, particularly well-populated with fireflies (so much more poetically known by their American nickname of lightning bugs) simply got rid of its public streetlights altogether, being so thoroughly drenched in a shining golden haze of insects that it didn’t need them anymore?

You don’t cultivate honeybees, you build vast lightning bug farms.

How absolutely extraordinary it would be to light your city using genetically-modified species of bioluminescent nocturnal birds, for instance, trained to nest at certain visually strategic points – a murmuration of bioluminescent starlings flies by your bedroom window, and your whole house fills with light – or to breed glowing moths, or to fill the city with new crops lit from within with chemical light. An agricultural lightsource takes root inside the city.

Using bioluminescent homing pigeons, you trace out paths in the air, like GPS drawing via Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds.

An office lobby lit only by vast aquariums full of bioluminescent fish!

Bioluminescent organisms are the future of architectural ornament.

[Image: A bioluminescent tobacco plant, via Wikivisual].

[Image: A bioluminescent tobacco plant, via Wikivisual].

On the other hand, I don’t want to strain for moments of poetry here, when this might actually be a practical idea.

After all, how might architects, landscape architects, and industrial designers incorporate bioluminescence into their work?

Perhaps there really will be a way to using glowing vines on the sides of buildings as a non-electrical means of urban illumination.

Perhaps glowing tides of bioluminescent algae really could be cultivated in the Thames – and you could win the Turner Prize for doing so. Kids would sit on the edges of bridges all night, as serpentine forms of living light snake by in the waters below.

Perhaps there really will be glowing birds nesting in the canopies of Central Park, sound asleep above the heads of passing joggers.

Perhaps the computer screen you’re reading this on really will someday be an organism, not much different from a rare tropical fish – a kind of living browser – that simply camouflages new images into existence.

Perhaps going off-grid will mean turning on the lifeforms around us.

[Image: From episode 9 of Patriot, courtesy Amazon Studios.]

[Image: From episode 9 of Patriot, courtesy Amazon Studios.] [Image: From episode 9 of Patriot, courtesy Amazon Studios.]

[Image: From episode 9 of Patriot, courtesy Amazon Studios.] [Image: “Lightning Bugs in York, PA,” by

[Image: “Lightning Bugs in York, PA,” by  [Image: Bioluminescent billboards on one of the Galapagos Islands, by Octave Perrault].

[Image: Bioluminescent billboards on one of the Galapagos Islands, by Octave Perrault]. [Image: Bioluminescent billboards by

[Image: Bioluminescent billboards by  [Image: A map of the

[Image: A map of the  [Image: A bioluminescent tobacco plant, via

[Image: A bioluminescent tobacco plant, via