[Images: Via Peter Moore’s piece on “dueling weathermen” over at Nautilus].

As mentioned in the previous post, I recently had the pleasure of reading Peter Moore’s new book, The Weather Experiment. There are many interesting things in it—including the London “time ball,” of course—but one scene in particular stood out for its odd design details.

In 19th-century Philadelphia, Moore explains, climate scientist James Espy began building a miniature model of the earth’s atmosphere in his back garden on Chestnut Street. This microcosm was a nephelescope, or “an air pump attached to a barometer and a tubular vessel—something of an early cloud chamber.”

Espy’s larger goal here was to understand the sky as a complexly marbled world of colliding fronts and rising air columns, “an entire dynamic weather system” that could perhaps best be studied through replication.

The sky, that is, could be modeled—and, if correctly modeled, predicted. It was just a question of understanding the physics of “ascending currents of warm air drawing up vapor, the vapor condensing at a specific height, expanding and forming clouds, and then the water droplets falling back to earth.”

Under different atmospheric conditions, Espy realized, this system of vaporous circulation was capable of producing every type of precipitation: rain, snow, or hail. His task then became to calculate specific circumstances. What temperature was needed to produce snow? What expansion of water vapor would produce would be required to generate a twenty-mile-wide hailstorm?

Why not construct a smaller version of this in your own backyard and watch it go? A garden for modeling the sky.

I love this next bit: “To work with maximum speed,” Moore writes, “he had painted his fence white, so he could use it like an enormous notebook.” The entire fence was soon “covered with figures and calculations,” Espy’s niece recalled, till “not a spot remained for another sum or calculation.”

Espy’s outdoor whiteboard, wrapped around a “space transformed into an atmospheric laboratory, filled with vessels of water, numerous thermometers and hygrometers,” in Moore’s words, would make an interesting sight today, resembling something so much as a set designed for an avant-garde theatrical troupe or a student project at the Bartlett School of Architecture.

Indeed, Espy’s lost sky-math garden suggests some interesting spatial possibilities for a sort of outdoor scientific park, a piece of urban land replicating the atmosphere through both instruments and equations.

[Image: Drone footage of a Cornwall garden sinkhole, via the

[Image: Drone footage of a Cornwall garden sinkhole, via the  [Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Photo courtesy

[Image: Rendering of a possible “BaseTern” landscape by students Brett Harris, Andrew D’Arcy, and Heidi Petersen, via

[Image: Rendering of a possible “BaseTern” landscape by students Brett Harris, Andrew D’Arcy, and Heidi Petersen, via

[Images: (top) Milwaukee’s Marquette interchange, nearly the same size as the city it cuts through; (bottom) Milwaukee before the interchange. Images via

[Images: (top) Milwaukee’s Marquette interchange, nearly the same size as the city it cuts through; (bottom) Milwaukee before the interchange. Images via

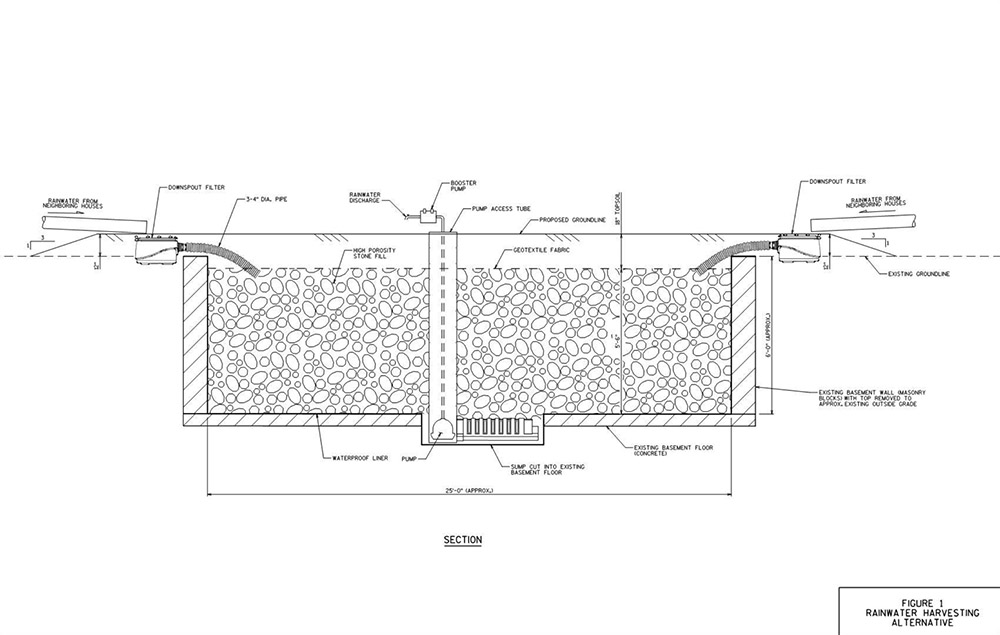

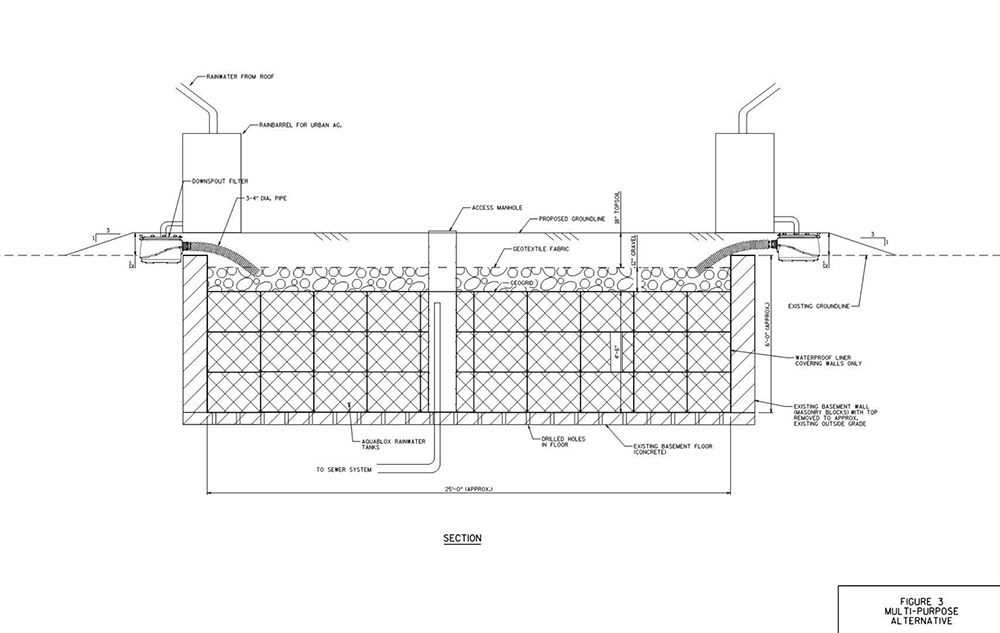

[Images: Two BaseTern design diagrams, taken from Milwaukee’s “

[Images: Two BaseTern design diagrams, taken from Milwaukee’s “