Don’t forget “the distant future,” an article in New Scientist warns, referring to an era 7.5 billion years from now – when “the sun will loom 250 times larger in the sky than it is today, and it will scorch the Earth beyond recognition.”

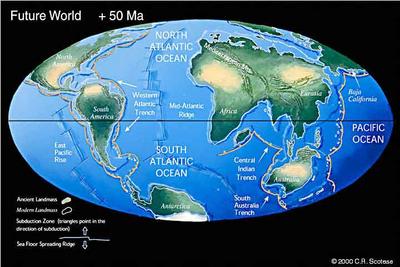

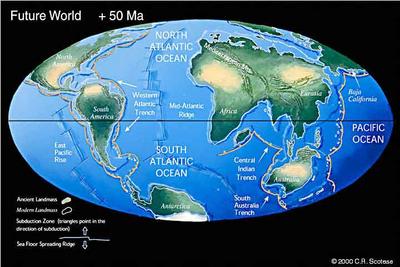

That Earth, however, will be unrecognizable, geologically reconfigured into something called Pangaea Ultima: “Existing [subduction] zones on the western edge of the Atlantic ocean should seed a giant north-south rift that swallows heavy, old oceanic crust. The Atlantic will start to shrink, sending the Americas crashing back into the merged Euro-African continent. So roughly 250 million years from now, most of the world’s land mass will once again be joined together in a new supercontinent that [Christopher] Scotese and his colleagues [at U-Texas, Arlington] have dubbed Pangaea Ultima.”

[Images: Pangaea Ultima, or the Earth in 250 million years, from Christopher Scotese’s website. It’s interesting here to imagine where the cities of today might end up in this configuration, if Manhattan will collide, say, with the docklands of London, and what that new city would then be called – and could you set a novel in a space like that? You look out and see Manhattan coming toward you on the horizon, at the speed of a fingernail growing, and you take little rowboats out to visit it on long summer afternoons, that ghost city adrift on mantled currents of earthquake-laden rock. Or would it be possible for an architect – or two architects, on opposite sides of the ocean – to design, today, different buildings meant to merge in millions of years, to collide with each other and link into one building through plate tectonics, a kind of delayed, virtual, urban self-completion via continental drift… Cairo-Athens: an architectural puzzle assembled by the Earth’s own geological mechanisms].

[Images: Pangaea Ultima, or the Earth in 250 million years, from Christopher Scotese’s website. It’s interesting here to imagine where the cities of today might end up in this configuration, if Manhattan will collide, say, with the docklands of London, and what that new city would then be called – and could you set a novel in a space like that? You look out and see Manhattan coming toward you on the horizon, at the speed of a fingernail growing, and you take little rowboats out to visit it on long summer afternoons, that ghost city adrift on mantled currents of earthquake-laden rock. Or would it be possible for an architect – or two architects, on opposite sides of the ocean – to design, today, different buildings meant to merge in millions of years, to collide with each other and link into one building through plate tectonics, a kind of delayed, virtual, urban self-completion via continental drift… Cairo-Athens: an architectural puzzle assembled by the Earth’s own geological mechanisms].

After Pangaea Ultima, runaway greenhouse warming and a literally expanding sun will mean that everything “gets worse. In 1.2 billion years, the sun will be about 15 per cent brighter than it is today. The surface temperature on Earth will reach between 60 and 70°C and the… oceans will all but disappear, leaving vast dry salt flats, and the cogs and gears of Earth’s shifting continents will grind to a halt. Complex animal life will almost certainly have died out.”

Jeffrey Kargel, from the U.S. Geological Survey’s office in Flagstaff, Arizona, offers his own vision of planetwide erosion: “‘Imagine a steaming Mississippi river delta with 90 per cent of the water gone. There’ll be lots of sluggish streams and the whole Earth will be flattening out. All the mountains will be eroded down to their roots.’ Huge swathes of the Earth might resemble today’s deserts in Nevada and southern Arizona, with low, rugged mountains almost buried in their own rubble.”

Kargel believes that the Earth might even become “‘tidally locked’ to the sun. In other words, one side of the planet will be in permanent daylight while the other side will always be dark.”

Kargel believes that the Earth might even become “‘tidally locked’ to the sun. In other words, one side of the planet will be in permanent daylight while the other side will always be dark.”

The side of the planet always in the glare of triumphant Apollo will eventually consist of huge roiling seas of liquid rock – perhaps ready for the return of Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner. “7.57 billion years from now, the magma ocean directly in the glare of the sun will reach almost 2200°C. ‘At that kind of temperature, the magma will start to evaporate,’ (!) says Kargel.”

Meanwhile, “Kargel thinks the night side of the Earth could be… about -240°C. And this bizarre hot-and-cold Earth will set up some exotic weather patterns.”

[Image: “Exotic” future weather systems (from New Scientist); worth enlarging. We could thus anticipate a market in weather futures: the financial coupling of climatology and the global reinsurance industry, but, here, gone deep time and virtual].

[Image: “Exotic” future weather systems (from New Scientist); worth enlarging. We could thus anticipate a market in weather futures: the financial coupling of climatology and the global reinsurance industry, but, here, gone deep time and virtual].

“On the hot side, metals like silicon, magnesium and iron, and their oxides, will evaporate out of the magma sea. In the warm twilight zones, they’ll condense back down. ‘You’ll see iron rain, maybe silicon monoxide snow,’ says Kargel. Meanwhile potassium and sodium snow will fall from colder dusky skies.”

So it would seem possible, amidst all this, to figure out, for instance, the melting point of Manhattan, ie. the point at which rivers of liquid architecture will start flowing down from the terraces of uninhabited high-rise flats, when the top of the Chrysler Building, all but invisible behind superheated orange clouds of toxic greenhouse gases, will form a glistening silver stream of pure metal boiling down into the half-closed Atlantic Ocean.

If cities are viewed, in this instance, as geological deposits, then surely there would be a way to account for them in the equations of future geophysicists: all of London reduced to a pool of molten steel, swept by currents of gelatinous glass, as sedimentary rocks made of abraded marble, granite, and limestone form from compression in the lower depths. A new Thames of liquid windows, former walls.

Any account of a future Earth, in other words, melting under the glare of a red giant sun, should include the future of cities, where buildings become rivers and subways will fossilize.

All cities, we could say, are geology waiting to happen.

(See BLDGBLOG’s Urban fossil value for more).

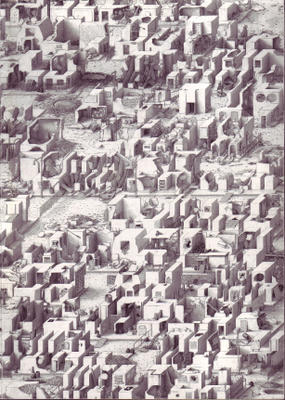

[Image 1:

[Image 1: