Photographer Gisela Erlacher has been documenting “the spaces found hidden underneath highways and flyovers across Europe and China,” as seen in the many photos posted over at Creative Boom. “Each photograph reveals not only her own fascination with these massive concrete monstrosities, but also her interest in how they’re now being used by the people who choose to wedge themselves into these forgotten areas.”

Month: January 2016

The Architecture of Readymade Air

[Image: Haus-Rucker-Co, Grüne Lunge (Green Lung), Kunsthalle Hamburg (1973); photo by Haus-Rucker Co, courtesy of the Archive Zamp Kelp; via Walker Art Center].

[Image: Haus-Rucker-Co, Grüne Lunge (Green Lung), Kunsthalle Hamburg (1973); photo by Haus-Rucker Co, courtesy of the Archive Zamp Kelp; via Walker Art Center].

I’ve got a short post up over at the Walker Art Center, as part of their new Hippie Modernism show featuring work by Archigram, Ant Farm, Haus-Rucker-Co, and many more. The exhibition, curated by Andrew Blauvelt, “examines the intersections of art, architecture, and design with the counterculture of the 1960s and early 1970s.”

A time of great upheaval, this period witnessed a variety of radical experiments that challenged societal and professional expectations, overturned traditional hierarchies, explored new media and materials, and formed alternative communities and new ways of living and working together. During this key moment, many artists, architects, and designers individually and collectively began a search for a new kind of utopia, whether technological, ecological, or political, and with it offered a critique of the existing society.

While the exhibition and its accompanying, very nicely designed catalog are both worth checking out in full, my post looks at a specific project by Haus-Rucker-Co called Grüne Lunge (Green Lung), seen in the above image.

Green Lung pumped artificially conditioned indoor air from within the galleries of Hamburg’s Kunsthalle to members of the public passing, by way of transparent helmets mounted outside; the museum’s internal atmosphere was thus treated as a kind of readymade object, “playing with questions of inside vs. outside, of public vs. private, of enclosure vs. space.”

[Image: Haus-Rucker-Co, Oase Nr. 7 (Oasis No. 7), installation at Documenta 5, Kassel (1972); via Walker Art Center].

[Image: Haus-Rucker-Co, Oase Nr. 7 (Oasis No. 7), installation at Documenta 5, Kassel (1972); via Walker Art Center].

Put into the context of Haus-Rucker-Co’s general use of inflatables, as well as today’s emerging fresh-air market—with multiple links explaining this in the actual post—I suggest that what was once an almost absurdist art world provocation has, today, in the form of bottled air, become an unexpectedly viable business model.

In any case, check out the post and the larger Hippie Modernism exhibition if you get the chance.

Marine Acoustic Zones

Outside looks at the idea of “acoustic sanctuaries” in the sea, designed to help marine life communicate free of “anthropogenic noise,” whether created by military sonar or commercial shipping. Meanwhile, how much would I love to visit an “acoustic sanctuary” on land—a landscape deliberately cleared of “anthropogenic noise”—almost like the sound gardens and acoustic forestry of a designer like David Benqué.

Avian Infrastructure

[Image: The turkey vulture’s “verification flight pattern,” taken from “The Role of Olfaction in Food Location by the Turkey Vulture” by Kenneth E. Stager (PDF)].

[Image: The turkey vulture’s “verification flight pattern,” taken from “The Role of Olfaction in Food Location by the Turkey Vulture” by Kenneth E. Stager (PDF)].

In an article for New Scientist last year, I wrote about the expansion of urban infrastructure to include animal life, from pigs serving a de facto waste-management role in cities such as Cairo to falcons being used to patrol a Santa Monica business park against, less welcome species.

It was thus interesting to read last night that the noxious smell artificially introduced to otherwise odorless natural gas was originally added, at least partially, because it would attract turkey vultures.

In a 1964 paper by Kenneth E. Stager called “The Role of Olfaction in Food Location by the Turkey Vulture” (PDF) we read that the “decision to conduct field tests with ethyl mercaptan (CH3CH2SH) as an olfactory attractant for turkey vultures came as a result of conversations with field engineers of the Union Oil Company of California.” Its purpose would be “to aid in locating leaks in natural gas lines”:

It was suggested to them by a company engineer in Texas that an effective way of locating line leaks in rough terrain was to introduce a heavy concentration of ethyl mercaptan into the line and then patrol the route and observe the concentrations of turkey vultures circling or sitting on the ground at definite points along the line… A high concentration of ethyl mercaptan was introduced into the forty-two miles of gas line and a traverse of the route was made. At several points along the line, turkey vultures were observed either circling or sitting on the ground. At those locations the odor of the ethyl mercaptan was very pronounced and examination of the line revealed the leaks.

There are at least two things worth highlighting here: one is the strange image of 20th-century oil company employees wandering through “rough terrain” in coordinated synchrony with families of turkey vultures, in effect bringing avian labor into the international supply chain of petroleum products.

It’s the turkey vulture as corporate companion species: a living being enlisted for assistance in shepherding—or flocking, as it were—natural gas to the final customer. It seems almost medieval.

But the second thing that seems worth commenting on is the broader implication that natural gas was made to smell like death—to smell like rotting corpses—thus becoming attractive to flocks of turkey vultures. This brings to mind Reza Negarestani’s book, Cyclonopedia, where Negarestani refers to the oil industry in only somewhat fictional terms as a kind of industrial cult organized around what he calls “the black corpse of the sun”: that is, oil, with all of its volatile by-products, the remnant hydrocarbons of once-living things, transformed through millions of years of burial.

That we would make petroleum gas smell like dead animals seems almost perfectly ironic, giving this image of necromantic Union Oil employees out scouting the backlands of Texas and California looking for gas leaks, following airborne animal trails, an even more bizarre interpretive bearing.

(Vulture anecdote originally spotted on Twitter, thanks to a retweet from @carlzimmer).

To roam hither and thither rather than plod a linear course

The blog Landscapism takes a look at the “integral but largely uncharted topography” of the combe, the “amphitheatre-like landform that can be found at the head of a valley.” There, the post’s author writes, amidst lichen-covered rubble and interrupted creeks, “these watery starting lines disguised as cul-de-sacs are a gift to the rural flâneur; sheep tracks, streams, crags, ruined sheep folds—all encourage the curious visitor to roam hither and thither rather than plod a linear course.”

San Francisco Sub Hub

I’ve got a short post up over at Travel + Leisure about a speculative proposal to build a “submarine hub” at San Francisco’s Aquarium of the Bay that could be used as a base for exploring local seamounts, canyons, reefs, and escarpments. The post simultaneously looks at the pioneering undersea work of Sylvia Earle, who is involved with the project, and the utopian maritime architectural projects of groups such as Ant Farm.

Assassin’s Creed

In Mexico, the widespread assassination of mayors indicates that cartel violence “is evolving far beyond the drug trade. Cartels now fight for political power itself.” The murder of Gisela Mota, newly elected mayor of Temixco, “was part of a regional campaign by [a local cartel] to control town halls and rob the towns’ resources.” Ominously, while “kingpins rot in prisons and graves, their assassins have formed their own organizations, which can be even more violent and predatory.”

No One Here Gets Out Alive

Live in a high-rise? Consider having your heart attack elsewhere: a study in the Canadian Medical Association Journal looks at “the relation between floor of patient contact and survival after cardiac arrest in residential buildings.” Their take-away was almost Onion-like in its obviousness: “the survival rate after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest was lower for patients residing on higher floors.” It literally took too long for help to arrive. Yet the authors also suggest devising “interventions aimed at shortening response times to treatment of cardiac arrest in high-rise buildings,” as this “may increase survival”—which sounds like an interesting design challenge.

The Sky Roads of Kauttua

[Image: A 17th-century engraving by Abraham Bosse, scanned from the excellent Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge by Alberto Pérez-Gómez and Louise Pelletier].

[Image: A 17th-century engraving by Abraham Bosse, scanned from the excellent Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge by Alberto Pérez-Gómez and Louise Pelletier].

Thanks to airborne ice crystals reflecting street lights into the sky—an effect known as light pillars—the small Finnish village of Kauttua was greeted with an astral image of itself, as seen in a photo that made the rounds earlier this week. The town’s night-lit streets and buildings became uncanny constellations: the village as self-reflecting planetarium.

“How is that possible?” asks a helpful blog post by Fiona MacDonald. “When the temperature gets close to freezing,” she writes, “flat, hexagonal ice crystals can form in the air—not just up high, but also close to the ground. When this happens, these crystals essentially form a collective, giant mirror that can reflect a light source—such as a streetlight—back to the ground.” They are like ladders of light, or perhaps optical arrow chains, pulling images of our world up to space.

While the effect is already amazing, it’s worth noting that Kauttua is also the site of an ongoing search for an Iron Age village buried beneath the existing streets and property lines.

“The oldest archive source, a cadastral map from the year 1696, presents a homestead of 10 houses by the bridge leading across Eurajoki River,” we read over at Day of Archaeology. “A later cadastral map from 1790 presents large holdings of one farm at the same site and around it.” Today, however, there is little more than one surviving building, “an area of black soil” next to it, and “two light lines, presumably the earlier roads,” revealed in aerial photographs taken in 2008.

While there is obviously no connection between a lost Iron Age village and the ghostly street map that appeared in the sky over Kauttua last week, there is nonetheless something quite striking about the idea of a small village in the far north poised between two versions of itself: an underground web of old buildings and streets, now turned to black soil beneath the wheat fields, and this perfect, far more ethereal version, hovering there in a crystallography of light.

It’s almost as if a strange and other-worldly calendar exists, where, every summer, the town turns downward, scraping through soil and rock to uncover what it used to be, and then, each winter, it turns its eyes to the skies to see an inverted cartography, like some municipal zodiac, of its thriving streets.

(Thanks to Finnish novelist Hannu Rajaniemi, who first pointed this out to me on Twitter. “In Finland,” he wrote, “we make city maps in the sky out of light and snow crystals.”)

Rings

In the forests of northern Ontario, a “strange phenomenon” of large natural rings occurs, where thousands of circles, as large as two kilometers in diameter, appear in the remote landscape.

[Image: From the thesis “Geochemistry of Forest Rings in Northern Ontario: Identification of Ring Edge Processes in Peat and Soil” (PDF) by Kerstin M. Brauneder, University of Ottawa].

[Image: From the thesis “Geochemistry of Forest Rings in Northern Ontario: Identification of Ring Edge Processes in Peat and Soil” (PDF) by Kerstin M. Brauneder, University of Ottawa].

“From the air, these mysterious light-coloured rings of stunted tree growth are clearly visible,” the CBC explained back in 2008, “but on the ground, you could walk right through them without noticing them.”

Since they were discovered on aerial photos about 50 years ago, the rings have baffled biologists, geologists and foresters… Astronomers suggest the rings might be the result of meteor strikes. Prospectors wonder whether the formations signal diamond-bearing kimberlites, a type of igneous rock.

While it’s easy to get carried away with visions of supernatural tree rings growing of their own accord in the boreal forest, this is actually an example of where the likely scientific explanation is significantly more interesting than something explicitly otherworldly.

[Image: From the thesis “Geochemistry of Forest Rings in Northern Ontario: Identification of Ring Edge Processes in Peat and Soil” (PDF) by Kerstin M. Brander, University of Ottawa].

[Image: From the thesis “Geochemistry of Forest Rings in Northern Ontario: Identification of Ring Edge Processes in Peat and Soil” (PDF) by Kerstin M. Brander, University of Ottawa].

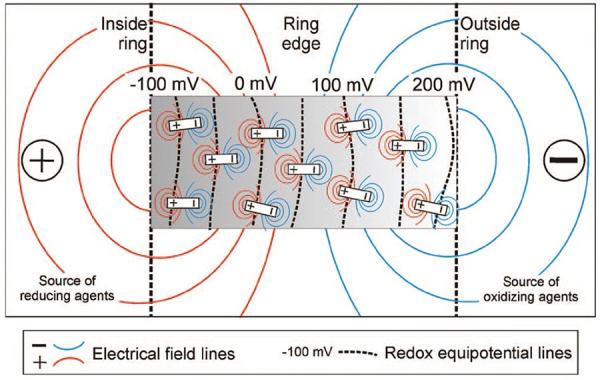

As geochemist Stew Hamilton suggested in 1998, the rings are most likely to be surface features caused by “reduced chimneys,” or “big centres of negative charge that frequently occur over metal deposits,” where a forest ring is simply “a special case of a reduced chimney.”

Reduced chimneys, meanwhile, are “giant electrochemical cells” in the ground that, as seen through the example of forest rings, can affect the way vegetation grows there.

[Image: Screen-grab from Google Maps].

[Image: Screen-grab from Google Maps].

One of many things worth highlighting here is this suggestion that the trees are being influenced from below by ambient electrochemical processes in the soil, set into motion by the region’s deep geology:

Hamilton was testing an analytical technique over a Matheson gold deposit to determine if there was any kind of geochemical surface signal. To his surprise, there were signals coming through 30 to 40 metres of glacial clay.

“We’re thinking there’s no way metals can move through clay 10,000 years after glaciation.”

After ruling out transport by ground water, diffusion and gas, he theorized it had to have been lifted to surface on electrical fields.

He applied the same theory to forest rings and discovered that they were also giant negatively charged cells.

Any source of negative charge will create a forest ring.

In landscape architecture terms, a forest ring—which Hamilton describes [PDF] as “a plant assemblage that is different from the surrounding forest making the features visible from the air”—could be seen as a kind of indirect electrochemical garden taking on a recognizably geometrical form without human intervention.

In effect, their shape is expressed from below. For ambitious future landscape designers, note that this implies a potential use of plantlife as a means for revealing naturally occurring electrical networks in the ground, where soil batteries and other forms of terrestrial electronics could articulate themselves through botanical side-effects.

That is, plant a forest; come back after twenty years; discover vast rings of negative electrochemical charge like smoke rings pushing upward from inside the earth.

Or, of course, you could reverse this: design for future landscape-architectural effects by formatting the deep soil of a given site, thus catalyzing subterranean electrochemical activity that, years if not generations later, would begin to have aesthetic effects.

[Image: From the paper “Spontaneous potential and redox responses over a forest ring” (PDF) by Stewart M. Hamilton and Keiko H. Hattori].

[Image: From the paper “Spontaneous potential and redox responses over a forest ring” (PDF) by Stewart M. Hamilton and Keiko H. Hattori].

But it gets weirder: as Hamilton’s fieldwork also revealed, there is a measurable “bulge in the water table that occurs over the entire length of the forest ring with a profound dip on the ring’s outer edge.” For Hamilton, this effect was “beyond science fiction,” he remarked to the trade journal Northern Ontario Business, “it’s unbelievable.”

What this means, he explained, is that “the water is being held up against gravity” by naturally occurring electrical fields.

[Image: From the paper “Spontaneous potential and redox responses over a forest ring” (PDF) by Stewart M. Hamilton and Keiko H. Hattori].

[Image: From the paper “Spontaneous potential and redox responses over a forest ring” (PDF) by Stewart M. Hamilton and Keiko H. Hattori].

Subsequent and still-ongoing research by other geologists and geochemists has shown that forest rings are also marked by the elevated presence of methane (which explains the “stunted tree growth”), caused by natural gas leaking up from geological structures beneath the forest.

Hamilton himself wrote, in a short report for the Ontario Geological Survey [PDF], that forest ring formation “may be due to upward methane seepage along geological structures from deeper sources,” and that this “may indicate deeper sources of natural gas in the James Bay Lowlands.”

Other hypotheses suggest that these forest rings could instead be surface indicators of diamond pipes and coal deposits—meaning that, given access to an aerial view, you can, in effect, “read” the earth’s biosphere as a living tissue of signs or symptoms through which deeper, non-biological phenomena (coal, diamonds, metals) are revealed.

[Image: Forest ring at N 49° 16′ 05″, W 83° 45′ 01″, via Google Maps].

[Image: Forest ring at N 49° 16′ 05″, W 83° 45′ 01″, via Google Maps].

Even better, these electrochemical effects stop on a macro-scale where the subsurface geology changes; as Hamilton points out [PDF], the “eastward disappearance of rings in Quebec occurs at the north-south Haricanna Moraine, which coincides with a sudden drop in the carbonate content of soils.”

If you recall that there were once naturally-occurring nuclear reactors burning away in the rocks below Gabon, then the implication here would be that large-scale geological formations, given the right slurry of carbonates, metals, and clays, can also form naturally-occurring super-batteries during particular phases of their existence.

To put this another way, through an accident of geology, what we refer to as “ground” in northern Ontario could actually be thought of a vast circuitboard of electrochemically active geological deposits, where an ambient negative charge in the soil has given rise to geometric shapes in the forest.

[Image: Forest rings at N 49° 29′ 48″, W 80° 05′ 40″, via Google Maps].

[Image: Forest rings at N 49° 29′ 48″, W 80° 05′ 40″, via Google Maps].

In any case, there is something incredible about the idea that you could be hiking through the forests of northern Ontario without ever knowing you’re surrounded by huge, invisible, negatively charged megastructures exhibiting geometric effects on the plantlife all around you.

Several years ago, I wrote a post about the future of the “sacred grove” for the Canadian Centre for Architecture, based on a paper called “The sacred groves of ancient Greece” by art historian Patrick Bowe. I mention this because it’s interesting to consider the forest rings of northern Ontario in the larger interpretive context of Bowe’s paper, not because there is any historical or empirical connection between the two, of course; but, rather, for the speculative value of questioning whether these types of anomalous forest-effects could, under certain cultural circumstances, carry symbolic weight. If they could, that is, become “sacred groves.”

Indeed, it is both thrilling and strange to imagine some future cult of electrical activity whose spaces of worship and gathering are remote boreal rings, circular phenomena in the far north where water moves against gravity and chemical reactions crackle outward through the soil, forcing forests to take symmetrical forms only visible from high above.

For more on forest rings, check out the CBC or Northern Ontario Business or check out any of the PDFs linked in this post.

The Politics of Land Use

USC geographer Travis Longcore on the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge occupation: “When the occupiers blithely talk of putting the land ‘to use’ again (as if scientific research, recreation, hunting, fishing, education, and all manner of public access were not ‘use’), the CNN reporter mindlessly repeats the trope, implying that the occupiers have a legitimate demand in wanting to work the land, as if it were some sort of de Tocquevillian tragedy that one of the most productive migratory bird stopover sites on the Pacific flyway was not being overrun with cattle by the ranchers from Utah. No, Malheur National Wildlife Refuge does not need to be worked, and CNN should have reporters that know better than to take the claim at face value.”