[Image: Geoglyphs of nowhere].

[Image: Geoglyphs of nowhere].

In the desert 100 miles northeast of Los Angeles is a suburb abandoned in advance of itself—the unfinished extension of a place called California City. Visible from above now are a series of badly paved streets carved into the dust and gravel, like some peculiarly American response to the Nazca Lines (or even the labyrinth at Chartres cathedral). The uninhabited street plan has become an abstract geoglyph—unintentional land art visible from airplanes—not a thriving community at all.

[Image: Empty streets from above, rotated 90º (north is to the right)].

[Image: Empty streets from above, rotated 90º (north is to the right)].

On Google Street View, distant structures like McMansions can be made out here and there amidst the ghost-grid, mirages of suburbia in the middle of nowhere.

And it’s a weird geography: two of the most prominent nearby landmarks include a prison—

[Image: The geometry of incarceration].

[Image: The geometry of incarceration].

—and an automobile test-driving facility run by Honda. There is also a visually spectacular boron mine to the southeast—it’s the largest open-pit mine in California, according to the Center for Land Use Interpretation—and an Air Force base.

To make things slightly more surreal, in an attempt to boost its economic fortunes, California City hired actor Erik Estrada, of CHiPs fame, to act as the town’s media spokesperson.

[Image: Spatial fossils of the 20th century].

[Image: Spatial fossils of the 20th century].

The history of the town itself is of a failed Californian utopia—in fact, incredibly, if completed, it was intended to rival Los Angeles. From the city’s Wikipedia entry:

California City had its origins in 1958 when real estate developer and sociology professor Nat Mendelsohn purchased 80,000 acres (320 km2) of Mojave Desert land with the aim of master-planning California’s next great city. He designed his model city, which he hoped would one day rival Los Angeles in size, around a Central Park with a 26-acre (11 ha) artificial lake. Growth did not happen anywhere close to what he expected. To this day a vast grid of crumbling paved roads, scarring vast stretches of the Mojave desert, intended to lay out residential blocks, extends well beyond the developed area of the city. A single look at satellite photos shows the extent of the scarred desert and how it stakes its claim to being California’s 3rd largest geographic city, 34th largest in the US. California City was incorporated in 1965.

I can see an amazing article being written about this place for GOOD magazine —”California and its Utopias,” say—or The New Yorker, or, for that matter, Atlas Obscura. The large-scale spatial remnants of an economic downturn, decades in advance of today’s recession.

[Images: Zooming in on the derelict grid].

[Images: Zooming in on the derelict grid].

Either way, and with any luck, a road trip out through the deserted inscriptions of this forgotten masterplan will hopefully beckon once BLDGBLOG moves back to Los Angeles.

(California City was pointed out to me a very long time ago by a BLDGBLOG reader—whose original email I can no longer find. If it was you who pointed this out to me, I owe you a huge thanks! David Donald—who also pointed out that California City was written up by The Vigorous North last year).

[Image: The front and back covers of

[Image: The front and back covers of  [Image: From

[Image: From

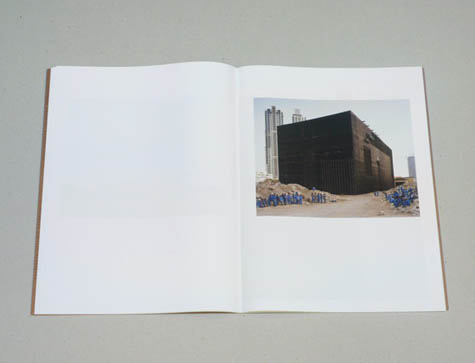

[Images: Some page spreads from

[Images: Some page spreads from  [Image: The cover to

[Image: The cover to  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Photo by Bas Princen, from

[Image: Photo by Bas Princen, from

[Images: Photos by Bas Princen, from

[Images: Photos by Bas Princen, from  [Image: An otherwise unrelated photograph of a house radically subsiding; courtesy of

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photograph of a house radically subsiding; courtesy of  [Image: Based on a

[Image: Based on a  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Photo by Steve Poole/Rex Features, via the

[Image: Photo by Steve Poole/Rex Features, via the  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: “Aqualta: 5th Avenue & 35th Street, NYC,” by

[Image: “Aqualta: 5th Avenue & 35th Street, NYC,” by  [Image: “Aqualta: Garment District, NYC,” by

[Image: “Aqualta: Garment District, NYC,” by

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: “Aqualta: Shibuya Station, Tokyo,” by

[Image: “Aqualta: Shibuya Station, Tokyo,” by  [Image: “Aqualta: 5th Avenue & 53rd Street, NYC,” by

[Image: “Aqualta: 5th Avenue & 53rd Street, NYC,” by