[Image: The water selection at Claridge’s, curated by Renaud Grégoire, food and beverage director].

[Image: The water selection at Claridge’s, curated by Renaud Grégoire, food and beverage director].

Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley.

The concept of terroir has its origins in French winemaking, as a means to describe the effect of geographic origin on taste. As a shorthand marker for both provenance and flavor, and as a sign of its burgeoning conceptual popularity, it has spread to encompass Kobe beef, San Marzano tomatoes, and even single-plantation chocolate.

But can water have terroir? What about the influence of the earth on water?

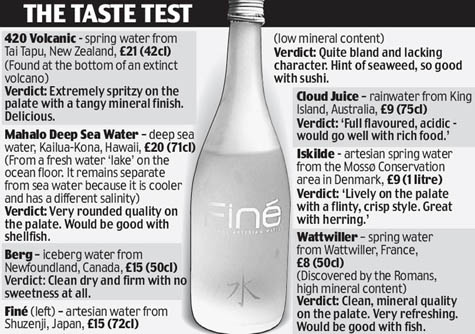

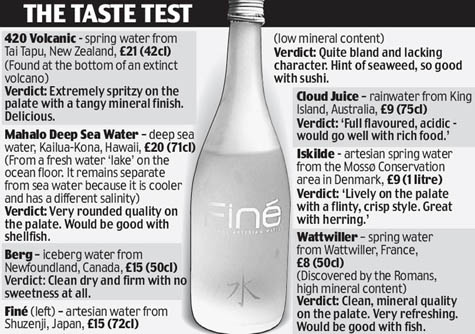

In late 2007, Claridge’s (a luxury hotel in Mayfair, London) caused a minor stir by introducing a “Water Menu.” The list features more than thirty mineral waters from around the world, described in terms of their origin and suggested flavor pairings.

Leaving aside a few obvious issues (such as the environmental impact of bottled water and the sheer economic wastefulness of sending multiple varieties of it to one hotel in England), it is hard not to appreciate the poetry of three-line exotic water biographies.

Take Mahalo Deep Sea Water, at £20 for 71cl, which comes from “a freshwater iceberg that melted thousands of years ago and, being of different temperature and salinity to the sea water around it, sank to become a lake at the bottom of the ocean floor. The water has been collected through a 3000ft pipeline off the shores of Hawaii.” According to the Daily Mail, Mahalo has a “very rounded quality on the palate” and it “would be good with shellfish.”

[Image: The Daily Mail‘s taste test results].

[Image: The Daily Mail‘s taste test results].

Meanwhile, Danish Iskilde‘s “flinty, crisp style” apparently derives from the Jutland aquifer’s complicated geology, consisting of interlaced deposits of quartz sand, clay, gravel, and soil. The most expensive (and possibly the most exciting) water on the menu is 420 Volcanic from New Zealand. Sourced from the Tai Tapu spring, which bubbles up through more then 650 feet of rock at the bottom of an extinct volcano, it is apparently “extremely spritzy on the palate with a tangy mineral finish.”

Claridge’s has since been joined by the Four Seasons in Sydney, and, according to The Guardian, “a handful of five-star Los Angeles hotels now employ water sommeliers to advise on the best water accompaniment to spiced braised belly pork or fillet of brill with parmentier of truffled leek.”

This same Guardian article goes on to recount the origins of Elsenham Water, which is described as “absolutely pure” and “very earthy—almost muddy,” depending on who you ask. Elsenham was discovered almost accidentally by Michael Johnstone, a former jam manufacturer; it is filtered over a 10-year period, in a confined chalk aquifer, half a mile below his abandoned jam factory and a neighboring industrial-sealant plant. Now, staff in white coats and hair nets fill up to 1,000 bottles daily “from an acrylic tank connected to pipes running into a hole in the ground.” Each bottle, priced at £12 for 75cl, is then polished by hand before it leaves the building.

According to Michael Mascha, former wine critic and author of Fine Waters: A Connoisseur’s Guide to the World’s Most Distinctive Bottled Waters, “water is in a transition from being considered a commodity to being considered a product.”

There is an undeniable Wild West gold-rush type of excitement to the idea of drilling for water in geologically auspicious locations. However, Mascha’s comment also implies that we might even begin to see the engineering of gourmet water products.

Loop tap water in a closed pressurized system for twenty years, through thick beds of pure northern Italian dolomite, and enjoy the lightly acidic result with chicken and fish. Better yet, blend it with water forced through a mixture of Forez and Porphyroid granite chips sourced from southwest France, stacked in a warehouse outside London to mimic in situ geological formations, to add a citrusy top note reminscent of Badoit.

A final spritz of oxygen ensures a silky mouthfeel—combined with the right designer packaging—and the burgeoning ranks of water connoisseurs will be lining up at your industrial plant for a taste.

[Previous posts by Nicola Twilley include Atmospheric Intoxication, Park Stories, and Zones of Exclusion].

[Image: Mike Bouchet’s Watershed being towed through Venice towards the Arsenale basin, against a backdrop of Italian palazzi].

[Image: Mike Bouchet’s Watershed being towed through Venice towards the Arsenale basin, against a backdrop of Italian palazzi]. [Image: Mike Bouchet’s Watershed goes down].

[Image: Mike Bouchet’s Watershed goes down]. [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: The massive

[Image: The massive  [Image: A Roman Triumph following the sack of Jerusalem].

[Image: A Roman Triumph following the sack of Jerusalem]. [Image:

[Image:  [Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: The water selection at

[Image: The water selection at  [Image: The

[Image: The  In fact, my early morning attempts to find domestic hotspots – putting my computer near the windows, or moving books and papers just a few more feet away – reminds me of stories I’ve read about high-end audio equipment aficionados, people who purchase arcane bits of scientifically dismissible, wildly overpriced stereo attachments in the hopes that they can affect, clarify, or otherwise improve their home-listening experience.

In fact, my early morning attempts to find domestic hotspots – putting my computer near the windows, or moving books and papers just a few more feet away – reminds me of stories I’ve read about high-end audio equipment aficionados, people who purchase arcane bits of scientifically dismissible, wildly overpriced stereo attachments in the hopes that they can affect, clarify, or otherwise improve their home-listening experience.