I thought it might be fun to post the course description and design brief for a course I’ll be teaching this semester at Columbia.

[Image: Photo via the Alfred Wegener Institute].

[Image: Photo via the Alfred Wegener Institute].

The idea behind the studio is to look at naturally occurring processes and forms—specifically, glaciers, islands, and storms—and to ask how these might be subject to architectural re-design.

We will begin our investigations by looking at three specific case-studies, including the practical techniques and concerns behind each. This research will then serve as the basis from which studio participants will create original glacier/island/storm design proposals.

GLACIER: For centuries, a vernacular tradition of constructing artificial glaciers in the Himalayas has been used to create reserves of ice from which freshwater can be reliably obtained during dry years. This is the glacier as non-electrical ice reserve, in other words; some of these structures have even received funding as international relief projects—for instance, by the Aga Khan Rural Support Program in Pakistan. Interestingly, the artificial glacier here becomes a philanthropic pursuit, falling somewhere between Architecture For Humanity and a sustainable water-bank.

GLACIER: For centuries, a vernacular tradition of constructing artificial glaciers in the Himalayas has been used to create reserves of ice from which freshwater can be reliably obtained during dry years. This is the glacier as non-electrical ice reserve, in other words; some of these structures have even received funding as international relief projects—for instance, by the Aga Khan Rural Support Program in Pakistan. Interestingly, the artificial glacier here becomes a philanthropic pursuit, falling somewhere between Architecture For Humanity and a sustainable water-bank.

Through an examination of glacier-building techniques, water requirements, and the thermal behavior of ice, we will both refine and re-imagine designs for self-sustaining artificial glaciers, for the ultimate purpose of storing fresh water.

But what specific tools and spatial techniques might this require? Further, what purposes beyond drought relief might an artificial glacier serve? There are myths, for instance, of Himalayan villagers building artificial glaciers to protect themselves against invasion, and perhaps we might even speculate that water shortages in Los Angeles could be relieved with a series of artificial glaciers maintained by the city’s Department of Water and Power at the headwaters of the Colorado River…

ISLAND: Building artificial islands using only sand and fill is relatively simple, but how might such structures be organically grown?

ISLAND: Building artificial islands using only sand and fill is relatively simple, but how might such structures be organically grown?

In the ocean south of Japan is a complex of reefs just slightly below the surface of the water; Japan claims that these reefs are, in fact, islands. This is no minor distinction: if the international community supports this claim, Japan would not only massively extend its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), complete with seabed-mining and fishing rights, but it would also block China from accessing those same resources. This would, however, also limit the ability of Chinese warships to patrol the region—and so the U.S. has publicly backed Japan’s territorial claim (China does not).

Okinawan scientists have thus been developing genetically-modified species of coral with the express idea of using these species to “grow” the reefs into a small but internationally recognized archipelago: the Okinotori Islands. Think of it as bio-technology put to use in the context of international sovereignty and the U.N. Law of the Sea.

The stakes are high—but, our studio will ask, by way of studying multiple forms of reef-building as well as materials such as Biorock, where might other such island-growing operations be politically and environmentally useful? Further, how might the resulting landforms be most interestingly designed? Assisted by a class visit from marine biologist Thomas Goreau, one-time collaborator of architect Wolf Hilbertz, we will look at the construction techniques and materials necessary for building wholly new artificial landforms.

STORM: For hundreds of years, a lightning storm called the Relampago del Catatumbo has flashed in the sky above Venezuela’s coastal Lake Maracaibo. The perfect mix of riverine topography, lake-borne humidity, and rain forest air currents has produced what can be described, with only slight exaggeration, as a permanent storm.

STORM: For hundreds of years, a lightning storm called the Relampago del Catatumbo has flashed in the sky above Venezuela’s coastal Lake Maracaibo. The perfect mix of riverine topography, lake-borne humidity, and rain forest air currents has produced what can be described, with only slight exaggeration, as a permanent storm.

This already fascinating anecdote takes on interesting spatial design implications when we read, for instance, that Shanghai city officials have expressed alarm at the inadvertent amplification of wind speeds through their city as more and more skyscrapers are erected there—demonstrating that architecture sometimes has violent climatological effects. Further, Beijing and Moscow both have recently declared urban weather control an explicit aim of their respective municipal governments—but who will be in charge of designing this new weather, and what role might architects and landscape architects play in its creation?

We will be putting these—and many other—examples of weather control together with urban, architectural, and landscape design studies in an attempt to produce atmospheric events. For instance, could we redesign Manhattan’s skyline to create a permanent storm over the city—or could we rid the five boroughs of storms altogether? And under what circumstances—drought-relief in the American southwest or Gulf Coast hurricane-deflection—might our efforts be most practically useful?

• • •The studio will be divided into three groups—one designing “glaciers,” one designing “islands,” one designing “storms.” Each group will mix vernacular building technologies with what sounds like science fiction to explore the fine line between architectural design and the amplified cultivation of natural processes. Importantly, this will be done not simply for the sake of doing so (although there will be a bit of that…), but to address much larger questions of international sovereignty, regional drought, global climate change, and more.

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: “GM12,” from

[Image: “GM12,” from  [Image: Photo via the

[Image: Photo via the  GLACIER: For centuries, a vernacular tradition of constructing

GLACIER: For centuries, a vernacular tradition of constructing  ISLAND: Building artificial islands using only sand and fill is relatively simple, but how might such structures be organically grown?

ISLAND: Building artificial islands using only sand and fill is relatively simple, but how might such structures be organically grown?  STORM: For hundreds of years, a lightning storm called the

STORM: For hundreds of years, a lightning storm called the  [Image: A C-141 Starlifter flying toward sunset; via

[Image: A C-141 Starlifter flying toward sunset; via  The competition hopes to inspire design research into “larger issues concerning the environment, global food production and the imperative to generate a sense of community in our urban and suburban neighborhoods.”

The competition hopes to inspire design research into “larger issues concerning the environment, global food production and the imperative to generate a sense of community in our urban and suburban neighborhoods.” [Image: Proposal for a

[Image: Proposal for a  [Image: Glimpses of the

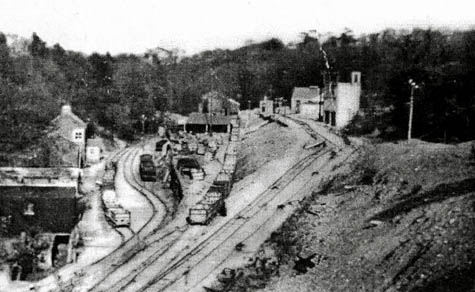

[Image: Glimpses of the  [Image: Archival view of the old mines at Grinkle, Yorkshire, UK].

[Image: Archival view of the old mines at Grinkle, Yorkshire, UK].

[Images: Planetary vaultwork; photos by

[Images: Planetary vaultwork; photos by  [Image: The earth is like a sandwich; photo by

[Image: The earth is like a sandwich; photo by