[Image: Via the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge].

[Image: Via the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge].

“We will put up the mountains. We will lay out the prairie. We will cut rivers to join the lakes.” So says the narrator of a nice piece of ecosystem fiction by my friend Scott Geiger published over at Nautilus.

This corporate spokesperson is building virgin terrain: “all-new country, elevated and secured from downstairs, with a growing complement of landforms, clean waters, ecologies, wilderness.”

I was reminded of Geiger’s work when I came across an old bookmark here on my computer, with a story that reads like something straight out of the golden age of science fiction: a corporate conglomerate, intent on spanning vast gulfs of space, finds itself engineering an entire ecosystem into existence on a remote stopping-off point, turning bare rocks into an oasis, in order to ensure that its empire can expand.

This could be the premise of a Hugo Award-winning interplanetary space opera—or it could be the real-life history of the Commercial Pacific Cable Company.

[Image: Via the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge].

[Image: Via the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge].

The Company was the first to lay a direct submarine cable from the United States to East Asia, but this required the use of a remote atoll, 1,300 miles northwest of Honolulu, called Midway, not yet famous for its role in World War II.

At the time, however, there was barely anything more there than “low, sandy island[s] with little vegetation,” considered by the firm’s operations manager to be “unfit for human habitation.” The tiny islands—some stretches no more than sandbars—would have been impossible to use, let alone to settle.

Like Geiger’s plucky terraforming super-company, putting up the mountains and laying out the prairie, the Cable Company and its island operations manager “initiated the long process of introducing hundreds of new species of flora and fauna to Midway.”

During this period, the superintendent imported soil from Honolulu and Guam to make a fresh vegetable garden and decorate the grounds. By 1921, approximately 9,000 tons of imported soil changed the sandy landscape forever. Today, the last living descendants of the Cable Company’s legacy still flutter about: their pet canaries. The cycad palm, Norfolk Island Pine, ironwood, coconut, the deciduous trees, everything seen around the cable compound is alien. Since Midway lacked both trees and herbivorous animals, the ironwood trees spread unchecked throughout the Atoll. What else came in with the soil? Ants, cockroaches, termites, centipedes; millions of insects which never could have made the journey on their own.

Strangely, the evolved remnants of this corporate ecosystem are now an international bird refuge, as if saving space for the feral pets of long-dead submarine cable operators.

[Image: Via the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge].

[Image: Via the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge].

The preserved ruins of old Cable Company buildings stand amidst the trees, surely now home to many of those “millions of insects which never could have made the journey on their own.” Indeed, “the four main Cable Company buildings, constructed of steel beams and concrete with twelve-inch thick first-story walls, have fought a tough battle with termites, corrosion, and shifting sands for nearly a century.”

It is a built environment even down to the biological scale—a kind of time-release landscape now firmly established and legally protected.

It’s worth pointing out, however, that the constructed frontier lands of Scott Geiger’s fictions and the national park of curated species still fluttering their wings at Midway share much with the even stranger story of terraforming performed by none other than Charles Darwin on Ascension Island.

This is, in the BBC’s words, “the amazing story of how the architect of evolution, Kew Gardens and the Royal Navy conspired to build a fully functioning, but totally artificial ecosystem.” It’s worth quoting at length:

Ascension was an arid island, buffeted by dry trade winds from southern Africa. Devoid of trees at the time of Darwin and [his friend, the botanist Joseph] Hooker’s visits, the little rain that did fall quickly evaporated away.

Egged on by Darwin, in 1847 Hooker advised the Royal Navy to set in motion an elaborate plan. With the help of Kew Gardens—where Hooker’s father was director—shipments of trees were to be sent to Ascension.

The idea was breathtakingly simple. Trees would capture more rain, reduce evaporation and create rich, loamy soils. The “cinder” would become a garden.

So, beginning in 1850 and continuing year after year, ships started to come. Each deposited a motley assortment of plants from botanical gardens in Europe, South Africa and Argentina.

Soon, on the highest peak at 859m (2,817ft), great changes were afoot. By the late 1870s, eucalyptus, Norfolk Island pine, bamboo, and banana had all run riot.

It’s not a wilderness forest, then, but a feral garden “run riot” on the slopes of a remote, militarized island outpost (one photographed, I should add, by photographer Simon Norfolk, as discussed in this earlier interview on BLDGBLOG).

[Image: The introduced forestry of Ascension Island, via Google Maps].

[Image: The introduced forestry of Ascension Island, via Google Maps].

In a sense, Ascension’s fog-capturing forests are like the “destiny trees” from Scott Geiger’s story in Nautilus—where “there are trees now that allow you to select pretty much what form you want ten, fifteen, twenty years down the road”—only these are entire destiny landscapes, pieced together for their useful climatic side-effects.

For anyone who happened to catch my lecture at Penn this past March, the story of Ascension bears at least casual comparison to the research of Christine Hastorf at UC Berkeley. Hastorf has written about the “feral gardens” of the Maya, or abandoned landscapes once deeply cultivated but now shaggy and overgrown, all but indistinguishable from nature. For Hastorf, many of the environments we currently think of as Central American rain forest are, in fact, a kind of indirect landscape architecture, a terrain planted and pruned long ago and thus not wilderness at all.

Awesomely, the alien qualities of this cloud forest can be detected. As one ecologist remarked to the BBC after visiting the island, “I remember thinking, this is really weird… There were all kinds of plants that don’t belong together in nature, growing side by side. I only later found out about Darwin, Hooker and everything that had happened.” It was like stumbling upon a glitch in the matrix.

In the case of these islands, I love the fact that historically real human behavior competes, on every level, for sheer outlandishness with the best of science fiction for its creation of entire ecosystems in remote, otherwise inhospitable environments; advanced landscaping has become indistinguishable from planetology. And, in Scott Geiger’s case, I love the fact that the perceived weirdness of his story comes simply from the scale at which he describes these landscape activities being performed.

In other words, Geiger is describing something that actually happens all the time; we just refer to it as the suburbs, or even simply as landscaping, a near-ubiquitous spatial practice that is no less other-worldly for taking place one half-acre at a time.

[Image: A suburban landscape being rolled out into the forest like carpet; photo by BLDGBLOG].

[Image: A suburban landscape being rolled out into the forest like carpet; photo by BLDGBLOG].

Soon, even the discordant squares of grass seen in the above photograph will seem as if they’ve always been there: a terrain-like skin graft thriving under unlikely circumstances.

Think of a short piece in New Scientist earlier this year: “All this is forcing enthusiasts to reconsider what ‘nature’ really is. In many places, true wilderness vanished thousands of years ago, and the landscapes we think of as natural are largely artificial.”

Indeed, like something straight out of a Geiger short story, “thousands of years from now our descendants may think of African lions roaming American plains as ‘natural’ too.”

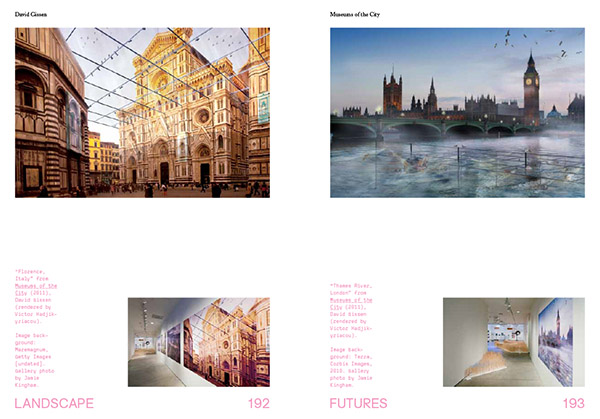

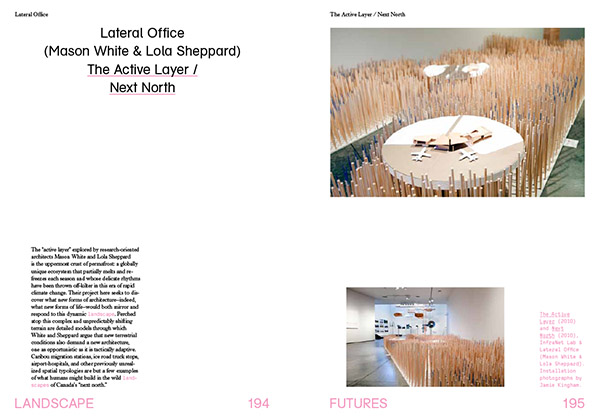

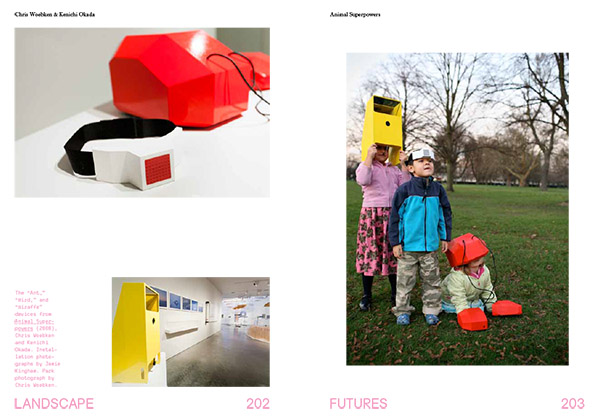

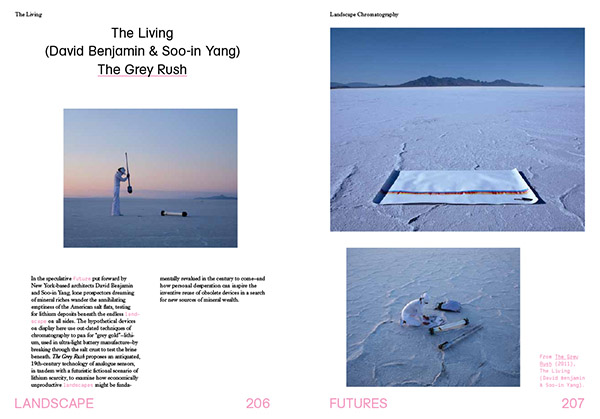

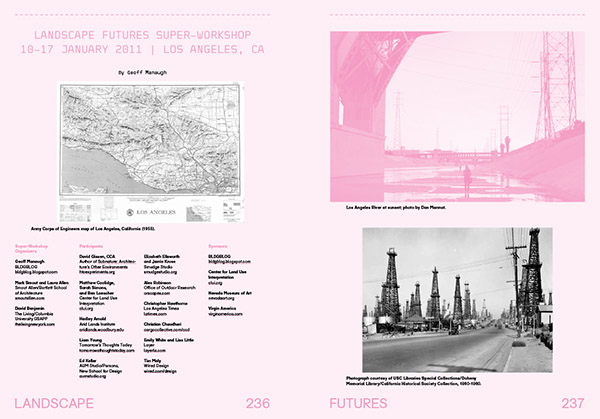

[Images: The cover of

[Images: The cover of

[Images: The opening spreads of

[Images: The opening spreads of

[Images: More spreads from

[Images: More spreads from

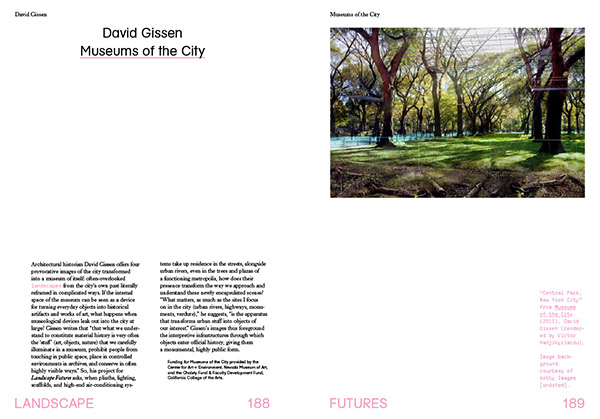

[Images: Spreads from

[Images: Spreads from

[Images: Installation shots from the Nevada Museum of Art, by Jamie Kingham and Dean Burton, including other views, from posters to renderings, from

[Images: Installation shots from the Nevada Museum of Art, by Jamie Kingham and Dean Burton, including other views, from posters to renderings, from

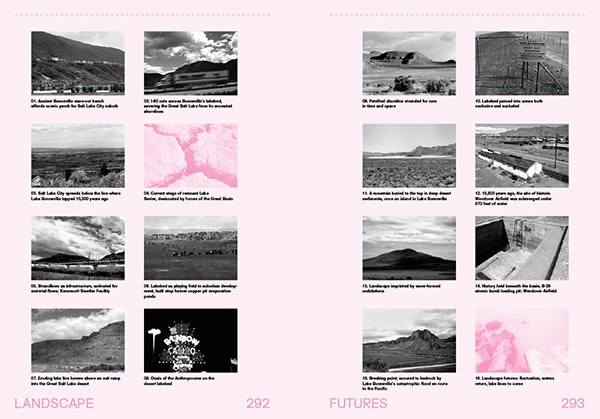

[Images: A few spreads from the Landscape Futures Sourcebook featured in

[Images: A few spreads from the Landscape Futures Sourcebook featured in