[Image: By Spiros Hadjidjanos, via Contemporary Art Daily].

[Image: By Spiros Hadjidjanos, via Contemporary Art Daily].

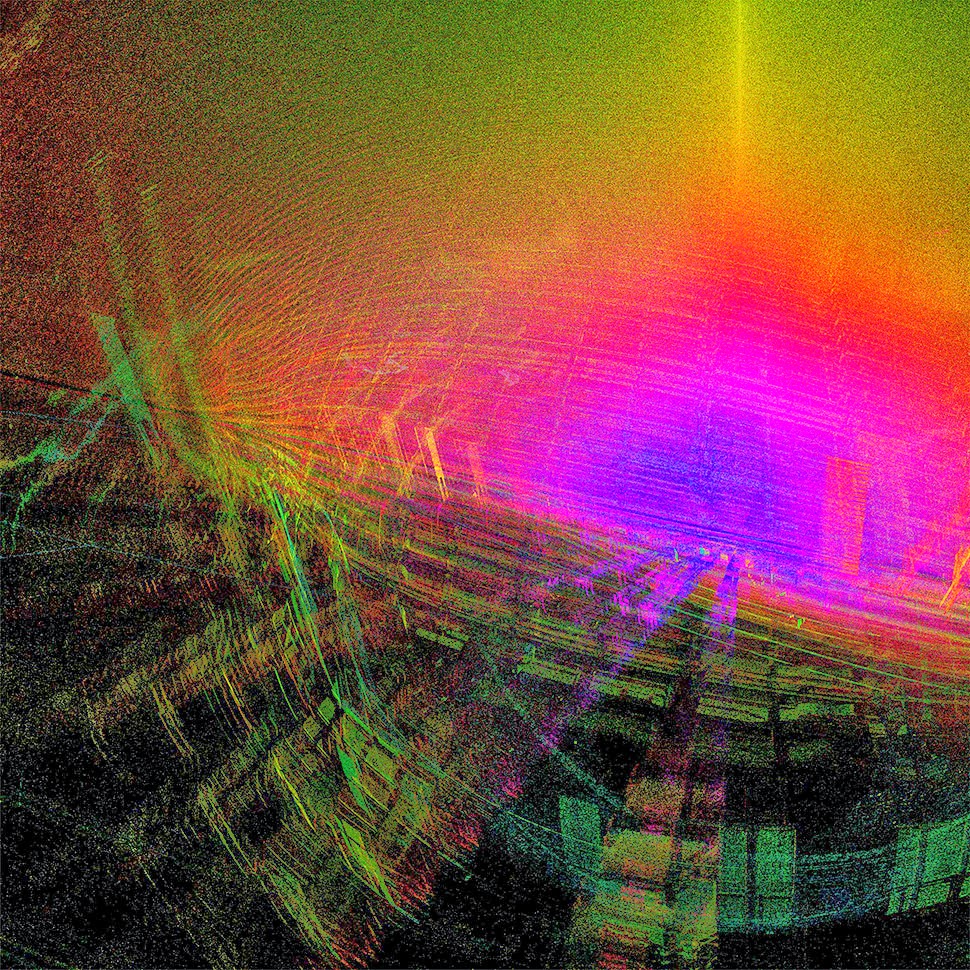

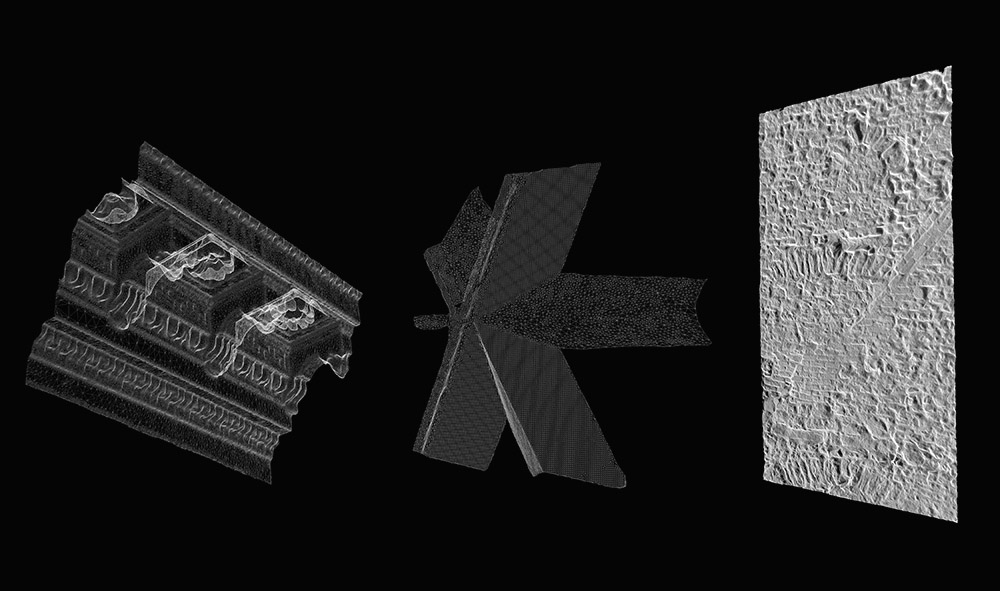

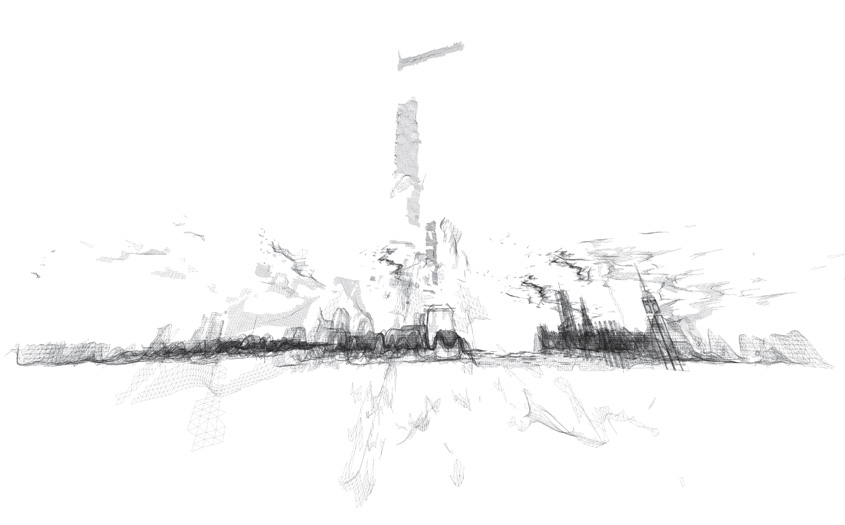

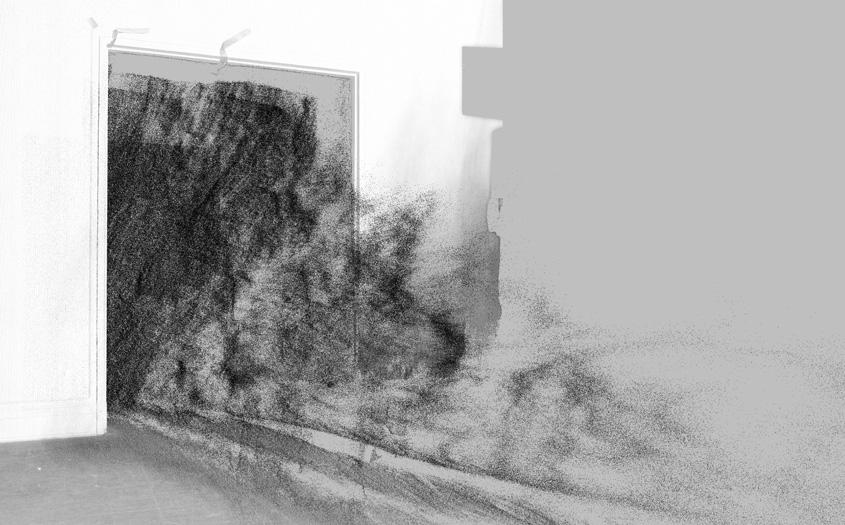

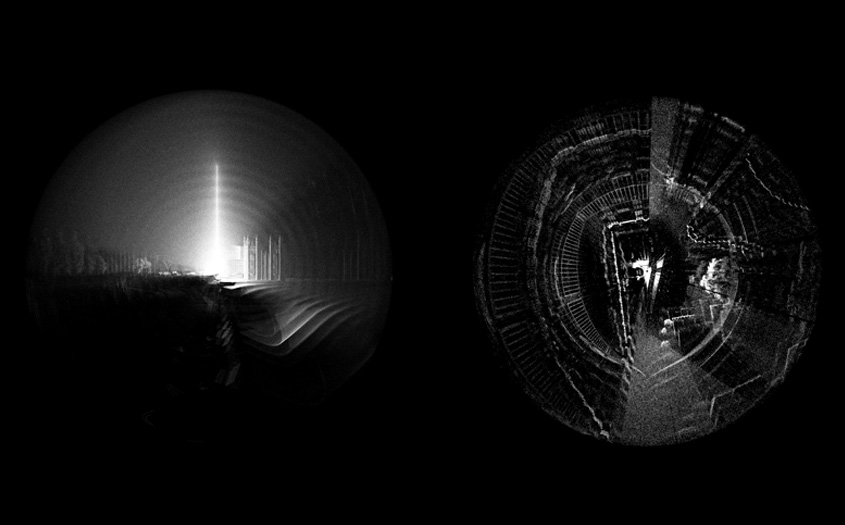

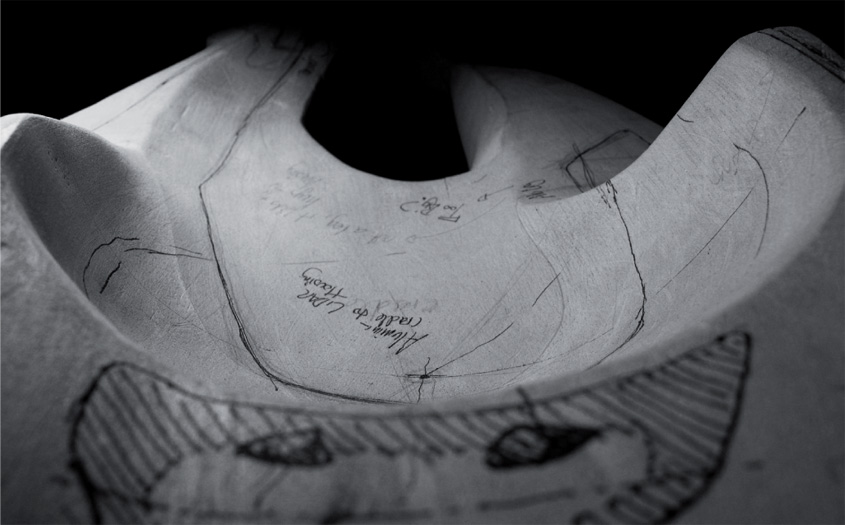

Artist Spiros Hadjidjanos has been using an interesting technique in his recent work, where he scans old photographs, turns their color or shading intensity into depth information, and then 3D-prints objects extracted from this. The effect is like pulling objects out of wormholes.

[Image: By Spiros Hadjidjanos, via Contemporary Art Daily].

[Image: By Spiros Hadjidjanos, via Contemporary Art Daily].

His experiments appear to have begun with a project focused specifically on Karl Blossfeldt’s classic book Urformen der Kunst; there, Blossfeldt published beautifully realized botanical photographs that fell somewhere between scientific taxonomy and human portraiture.

[Image: By Spiros Hadjidjanos, via Stylemag].

[Image: By Spiros Hadjidjanos, via Stylemag].

As Hi-Fructose explained earlier this summer, Hadjidjanos’s approach was to scan Blossfeldt’s images, then, “using complex information algorithms to add depth, [they] were printed as objects composed of hundreds of sharp needle-like aluminum-nylon points. Despite their space-age methods, the plants appear fossilized. Each node and vein is perfectly preserved for posterity.”

[Image: Via Spiros Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed].

[Image: Via Spiros Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed].

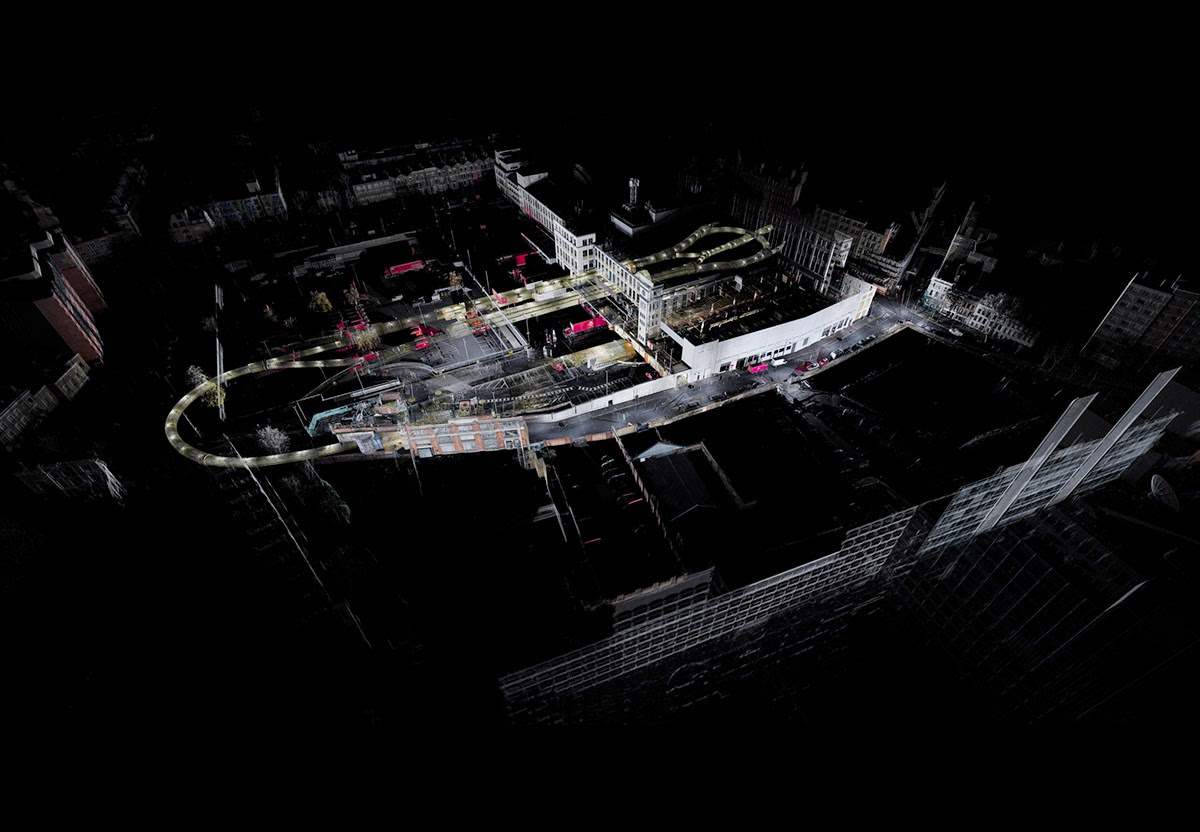

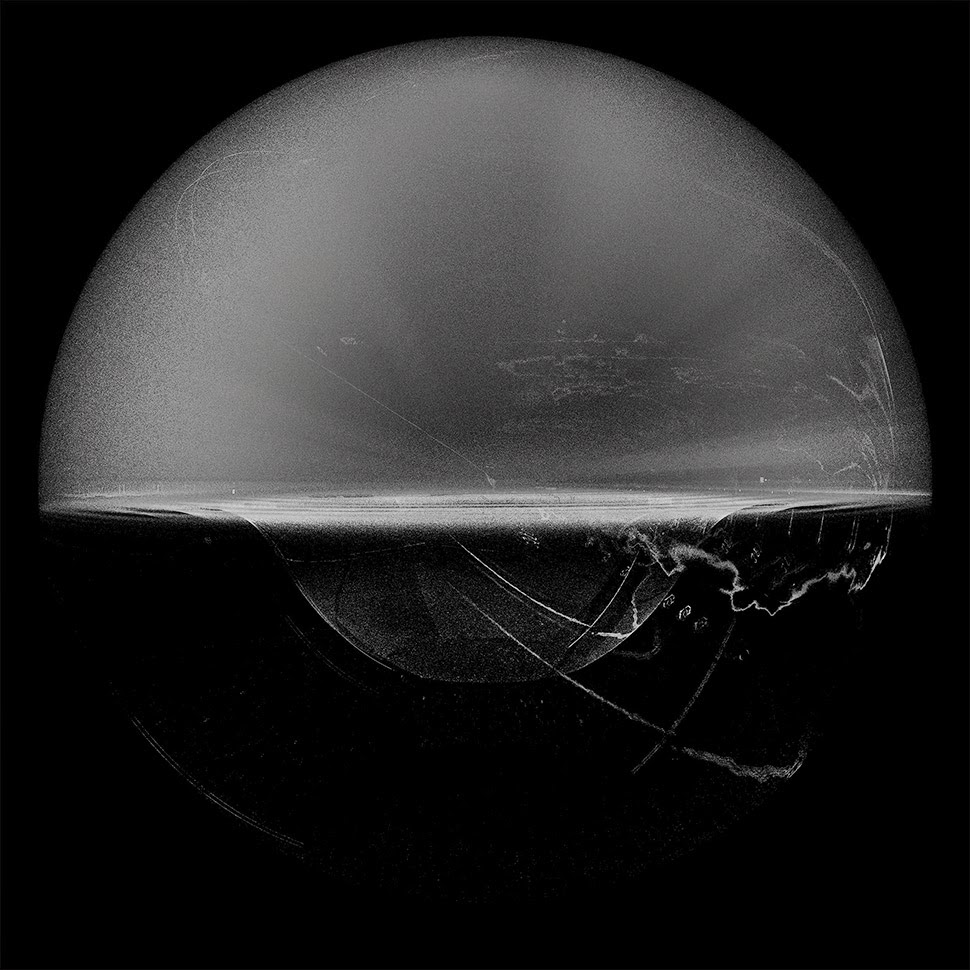

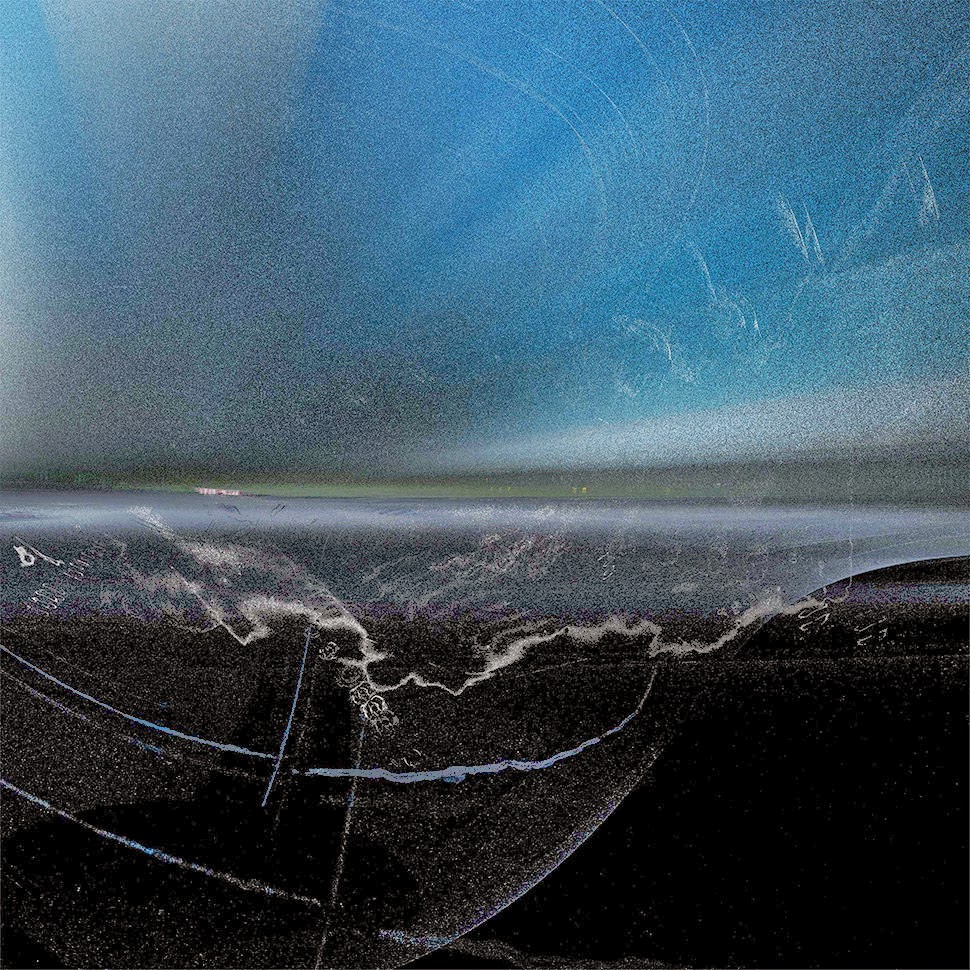

The results are pretty awesome—but I was especially drawn to this when I saw, on Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed, that he had started to apply this to architectural motifs.

2D architectural images—scanned and translated into operable depth information—can then be realized as blurred and imperfect 3D objects, spectral secondary reproductions that are almost like digitally compressed, 3D versions of the original photograph.

[Image: Via Spiros Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed].

[Image: Via Spiros Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed].

It’s a deliberately lo-fi, representationally imperfect way of bringing architectural fragments back to life, as if unpeeling partial buildings from the crumbling pages of a library, a digital wizardry of extracting space from surface.

[Image: Via Spiros Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed].

[Image: Via Spiros Hadjidjanos’s Instagram feed].

There are many, many interesting things to discuss here—including three-dimensional data loss, object translations, and emerging aesthetics unique to scanning technology—but what particularly stands out to me is the implication that this is, in effect, photography pursued by other means.

In other words, through a combination of digital scanning and 3D-printing, these strange metallized nylon hybrids, depicting plinths, entablatures, finials, and other spatial details, are just a kind of depth photography, object-photographs that, when hung on a wall, become functionally indistinct from architecture.

[Image: A laser scan of the Pantheon, courtesy

[Image: A laser scan of the Pantheon, courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: In the ruined basements of architectural simultaneity;

[Image: In the ruined basements of architectural simultaneity;

[Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By  [Image: By

[Image: By

[Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Image: A “

[Image: A “ [Image: A “

[Image: A “

[Images: From the “

[Images: From the “ [Image:

[Image:

[Image: Scans of a

[Image: Scans of a

The London-based architectural group

The London-based architectural group  [Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: A hypothetical “stealth object,” resistant to laser-scanning, by ScanLAB].

[Images: A hypothetical “stealth object,” resistant to laser-scanning, by ScanLAB].