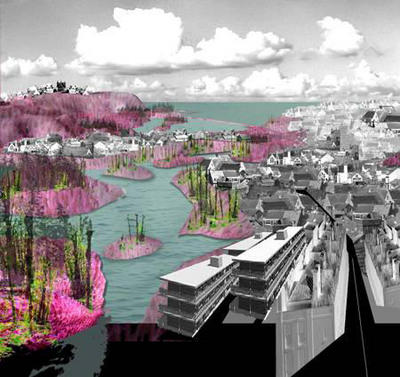

[Policing the earth: a military helicopter surveys a flooded metropolis under martial law.]

[Policing the earth: a military helicopter surveys a flooded metropolis under martial law.]

It’s too easy, not to mention slightly vindictive, to blame all of hurricane Katrina’s catastrophic impact and aftermath on the Army Corps of Engineers; but it is worth remembering that New Orleans – in fact the near totality of the lower Mississippi delta – is a manmade landscape that has become, over the last century at least, something of a military artifact. To say that New Orleans is, today, under martial law, is therefore almost redundant: its very landscape, for at least the last century, has never been under anything *but* martial law. The lower Mississippi delta is literally nothing less than landscape design by army hydrologists.

New Orleans as military hydrology.

Or, military urbanism as a hydrological project.

According to The Economist, “For much of the 20th century the federal government tampered with the Mississippi, to help shipping and – ironically – prevent floods. In the process it destroyed some 1m acres of coastal marshland around New Orleans – something which suited property developers, but removed much of the city’s natural protection against flooding. The city’s system of levees, itself somewhat undermaintained, was not able to cope.”

When even people within the Army Corps of Engineers began to warn that the hubristic landscape design methods of the US military might actually be inappropriate for what is a very muscular, flood-prone, not-to-be-fucked-with drainage basin, the warnings were taken – well, frankly, they were probably taken to be blatantly unpatriotic, knowing what’s happened to this country. But I digress.

“There is an irony,” The Economist elsewhere continues, “in this warning coming from the Corps of Engineers. Just as with the Everglades in Florida, New Orleans’s vulnerability has been exacerbated by the corps’ excellence in reshaping nature’s waterways to suit mankind’s whims. In the middle of the last century, engineers succeeded in re-plumbing the great Mississippi… [which simply] hastened erosion of the coastal marshes that used to buffer New Orleans, leaving the city needlessly exposed. Most of the metropolitan area lies below sea level on drained swamp land. Levees normally hold back the Mississippi and Lake Pontchartrain, but those were not designed to handle the waters that would come with such a powerful hurricane.”

Those same levees, in fact, as we all know, are actually now responsible for keeping the flood waters in:

“‘We’ve been living in this bowl,’ said Shea Penland, a coastal geologist who has studied storm threats to Louisiana for years,” in an interview with The New York Times. “‘And then Katrina broke channels into the bowl and the bowl filled. And now the bowl is connected to the Gulf of Mexico. We are going to have to close those inlets and then pump it dry.'”

But pumping the flooded city dry will be a “hard task,” according to the somewhat characteristic understatement of the BBC, in an article that then outlines the various steps of the engineering strategy involved (included new causeways, steel sheets, and 300-lb. sandbags).

But even if New Orleans is “pumped dry,” even if the city is eventually drained, even if commerce returns and the Big Easy’s population goes back to life as usual, there is still a much larger problem to face.

The Economist: “America’s Geological Survey has estimated that if nothing is done by 2050, Louisiana will lose another 700 square miles of coastal wetlands. Various local groups have long called for reconstruction of the marshes along the lines of the troubled $10 billion Everglades rejuvenation project. The New Orleans version, which would cost $4 billion more, would divert some 200,000 cubic feet of water each second from the Mississippi 60 miles through a channel to feed the existing marsh and to build two new deltas. The plan, which would also shut canals and locks to keep out salt water and would build artificial barrier islands, may find more adherents.”

Artificial barrier islands; 200,000 cubic feet of water each second; two new deltas: if at first you don’t succeed… try ever more elaborate feats of hydrological engineering. More of the disease is the cure for the disease. (See here for a much older – yet no less impressive for being small-scale – example of complex hydrological engineering).

Katrina, in this context, becomes a problem of landscape design.

The “hurricane” as an atmospherically-interactive, military-hydrological landscape problem.

[NASA satellite image: the Mississippi delta – several hundred square miles smaller than it should be.]

[NASA satellite image: the Mississippi delta – several hundred square miles smaller than it should be.]

It’s a question, in other words, of human geotechnical constructions and how they interact with the complex dynamics of the earth’s tropical atmosphere and waterways.

[Image: Nearly all of the Atlantic’s equatorial reserves of warm water contributed to the strength of the storm. A few levees didn’t stand a chance.]

So what may soon become known as the destruction of New Orleans was simply the violent and undeniable clarification of how bad certain examples of landscape architecture really can be. This should surprise no one – horrify everyone, but surprise no one.

[Images: The total collapse of the manmade landscape has all but drowned the city, turning it, in the words of the Associated Press, into “a ruined city awash in perhaps thousands of corpses, under siege from looters, and seething with anger and resentment”; and the complete failure of urban infrastructure – including federal emergency response, management, and planning, which has hamstrung itself by sending first-responders to fight in Iraq – has made what is fundamentally a problem of landscape design much worse.]

[Images: The total collapse of the manmade landscape has all but drowned the city, turning it, in the words of the Associated Press, into “a ruined city awash in perhaps thousands of corpses, under siege from looters, and seething with anger and resentment”; and the complete failure of urban infrastructure – including federal emergency response, management, and planning, which has hamstrung itself by sending first-responders to fight in Iraq – has made what is fundamentally a problem of landscape design much worse.]

Financially, could things have been different? Could the money now being spent in Iraq and on bogus Homeland Security projects have gone elsewhere – into FEMA, for instance, or into hydrologically better-designed levee projects on the outskirts of New Orleans? Or into some of those “artificial barrier islands” mentioned above (that BLDGBLOG would love to help design)?

Yes, the money could have been spent differently. But is further entrenching a particular manmade landscape – really, a kind of prosthetic earth’s surface, a concrete shell, of valves, dams, locks, levees, and holding ponds installed upon the lower Mississippi – really the answer? Perhaps; but equally possible is that *there should not be a city there*.

As Mike Davis writes in *Dead Cities*: “Nature is constantly straining against its chains: probing for weak points, cracks, faults, even a speck of rust. The forces at its command are of course colossal as a hurricane and as invisible as a baccilli. At either end of the scale, natural energies are capable of opening breaches that can quickly unravel the cultural order. (…) Environmental control demands continuous investment and systematic maintenance: whether building a multi-billion-dollar flood control system or simply weeding the garden. It is an inevitably Sisyphean labor.”

Davis then describes the 19th century novel *After London: or, Wild England* by Richard Jefferies, a book in which “the medievalized landscape of postapocalyptic England” is explored “less [as] a nightmare than [as] a deep ecologist’s dreamwish of wild powers re-enthroned. (William Morris reported that ‘absurd hopes curled around my heart as I read it.’)”

After its destruction, then, this is London: “As fields, house sites, and roads were overrun, the saplings of new forests appeared. Elms, ashes, oaks, sycamores, and horse chestnuts thrived chaotically in the ruins while more disciplined copses of fir, beech, and nut trees relentlessly expanded their circumferences.”

The city is soon home to huge flocks of kestrel hawks and owls; wild cattle; and thousands and thousands of cats, “now mostly grayish and longer in body than domestic ancestors.” (As per the film *Logan’s Run* – or see CNN: “New Orleans residents who return to their homes [will] face ‘a wilderness’ without power and drinking water that will be infested with poisonous snakes and fire ants.”)

Eventually, Davis recounts, “new species or subspecies [evolve] out of other former domesticates, (…) [and] the monstrous vegetative powers of feral nature begin a full-scale assault on London’s brick, stone, and iron skeleton.”

“As marsh recovered the floodplain, (…) [t]he hydraulic pressure of the flooded substratum of the city – underground passages, sewers, cellars, and drains – soon burst the foundations of homes and buildings, which in turn crumbled into rubble heaps, further impeding drainage.”

A “200-mile-long inland sea” soon forms: “Jefferies’s extinct London, in short, is a giant stopped-up toilet, threatening death as an ‘inevitable fate’ to anyone foolish enough to expose themselves to its poisonous miasma.”

It becomes, that is, a flooded city.

[Image: A corpse floats in the oil-coated lake that was once New Orleans.]

[Image: A corpse floats in the oil-coated lake that was once New Orleans.]

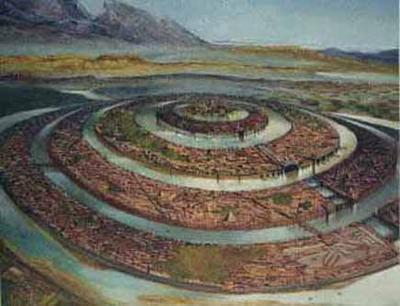

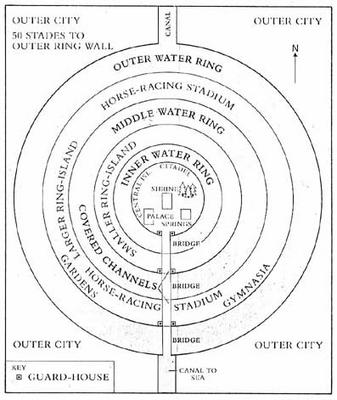

This thread continues in Katrina 2: New Atlantis (on flooded cities); and Katrina 3: Two anti-hurricane projects (on landscape climatology) – both on BLDGBLOG.

[Policing the earth: a military helicopter surveys a flooded metropolis under martial law.]

[Policing the earth: a military helicopter surveys a flooded metropolis under martial law.]

[NASA satellite image: the Mississippi delta – several hundred square miles smaller than it should be.]

[NASA satellite image: the Mississippi delta – several hundred square miles smaller than it should be.]

[Image: A corpse floats in the oil-coated lake that was once New Orleans.]

[Image: A corpse floats in the oil-coated lake that was once New Orleans.]