Since 2009, an annual Thrilling Wonder Stories event has taken place at the Architectural Association in London, bringing people together from multiple disciplines to explore the spaces between fiction, science, and design.

Since 2009, an annual Thrilling Wonder Stories event has taken place at the Architectural Association in London, bringing people together from multiple disciplines to explore the spaces between fiction, science, and design.

On one hand, these events take the form of an extended look into the role of architectural spaces—including real buildings, but also film sets, computer game environments, and spatial simulations—in propelling, staging, catalyzing, or otherwise framing narrative storylines. This requires speaking not only to architects, but to novelists, game developers, screenwriters, film set designers, and even Hollywood directors to discuss their own particular requirements for, and relationships to, the built environment—but also to ask, more specifically, how the spaces they design, describe, feature, or build affect the development of narrative.

This is the cultural dimension of the event—the “wonder stories.”

On the other hand, Thrilling Wonder Stories has also looked both to science and science fiction as resources of ideas that might play spatial roles in future design projects—where I use the word spatial, not architectural, very deliberately, so as not to limit this to a discussion of buildings. This means bringing in robot makers and biologists, geologists and geneticists, not to ask them about architecture but simply to learn about their work. The point, in other words, is not to extract architectural ideas from their research—as if fully formed building programs could somehow be pulled from a presentation about synthetic organisms—but simply to add to the overall mix of scientific (and science fictional) ideas available for reference in future design conversations.

This is the “thrilling wonder” side of the series.

[Images: Photos from Thrilling Wonder Stories 2 at the Architectural Association].

[Images: Photos from Thrilling Wonder Stories 2 at the Architectural Association].

To date, Liam Young, the event’s co-organizer, and I have hosted comics author Warren Ellis, architect Sir Peter Cook of Archigram, game critic Jim Rossignol, TED Fellow and architectural biologist Rachel Armstrong, novelists Will Self and Jeff VanderMeer, spatial provocateurs Ant Farm, designer Matt Webb of BERG, and more than a dozen other figures from the worlds of film, gaming, architecture, literature, engineering, science, interaction design, and more.

[Image: From “Animal Superpowers” by Chris Woebken and Kenichi Okada; Woebken will be speaking at Thrilling Wonder Stories 3 at Studio-X NYC].

[Image: From “Animal Superpowers” by Chris Woebken and Kenichi Okada; Woebken will be speaking at Thrilling Wonder Stories 3 at Studio-X NYC].

This year, we’re trying out an ambitious new format. Not only are we teaming up with Popular Science magazine as our media partner and co-organizer—so watch for content on popsci.com in the lead up to and during the event—but we are leading two simultaneous events: one at the Architectural Association in London, the other across the pond at Studio-X NYC.

So, on Friday, October 28th, Thrilling Wonder Stories 3—sponsored by the Architectural Association, Studio-X NYC, and Popular Science—kicks off in London with a truly phenomenal line-up. It’s an all day blow-out, lasting from noon to 10pm, featuring:

VINCENZO NATALI*

Director of Cube, Splice, and forthcoming feature films based on J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise and Neuromancer by William Gibson

BRUCE STERLING

Scifi author, commentator, and futurist

KEVIN SLAVIN

Game designer and theorist of “how algorithms shape our world“

ANDREW LOCKLEY

Academy Award-winning visual effects supervisor for Inception, compositing/2D supervisor for Batman Begins and Children of Men

PHILIP BEESLEY

Digital media artist and experimental architect

CHRISTIAN LORENZ SCHEURER

Concept artist and illustrator for computer games and films such as The Matrix, Dark City, The Fifth Element, and Superman Returns

CHARLIE TUESDAY GATES

Taxidermy artist and sculptor—to lead a live taxidermy workshop

DR. RODERICH GROSS AND THE NATURAL ROBOTICS LAB

Head of the Natural Robotics Lab at the University of Sheffield—to lead a live Swarm Robotics demonstration

GAVIN ROTHERY

Concept artist for Duncan Jones’s film Moon

GUSTAV HOEGEN

Animatronics engineer for Hellboy, Clash of the Titans, and Ridley Scott’s forthcoming film Prometheus

JULIAN BLEECKER

Designer, technologist, and researcher at the Los Angeles-based Near Future Laboratory

RADIO SCIENCE ORCHESTRA

Theremin-led electro-acoustic ensemble

SPOV

Motion graphics artists for Discovery Channel’s Future Weapons and Project Earth

ZELIG SOUND

Music, composition, and sound design for film and television

Better yet, Matt Jones of the ultra-talented design studio BERG will join Liam Young to serve as co-host for the day. Here’s a map for how to get there; the event is free but space is limited.

[Image: “Glass Weed” from Super-Natural Garden by Simone Ferracina; Ferracina will be speaking at Thrilling Wonder Stories 3 at Studio-X NYC].

[Image: “Glass Weed” from Super-Natural Garden by Simone Ferracina; Ferracina will be speaking at Thrilling Wonder Stories 3 at Studio-X NYC].

That same day—Friday, October 28th—over at Studio-X NYC, Thrilling Wonder Stories 3 will kick off at 1pm local time, lasting till 4 or 4:30pm. Speaking that day are:

NICHOLAS DE MONCHAUX

Architect and author of Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo

HARI KUNZRU

Novelist and author of Gods Without Men, Transmission, and The Impressionist

BJARKE INGELS

Architect, WSJ Magazine 2011 architectural innovator of the year, and author of Yes Is More: An Archicomic on Architectural Evolution

SETH FLETCHER

Science writer, senior editor of Popular Science, and author of Bottled Lightning: Superbatteries, Electric Cars, and the New Lithium Economy

JACE CLAYTON AND LINDSAY CUFF OF NETTLE

Nettle’s new album, El Resplandor, is a speculative soundtrack for an unmade remake of The Shining, set in a luxury hotel in Dubai

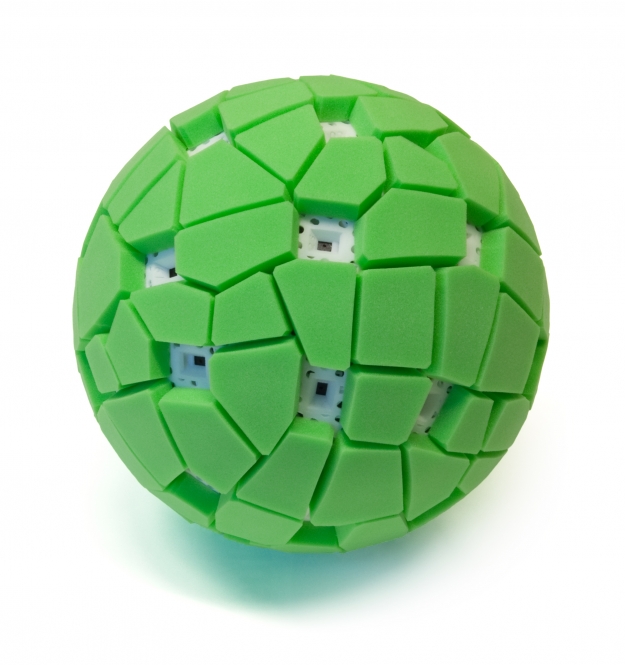

[Image: One of many evolutionary robotic research projects by Hod Lipson, featured in this PDF; Lipson will be speaking at Thrilling Wonder Stories 3 at Studio-X NYC].

[Image: One of many evolutionary robotic research projects by Hod Lipson, featured in this PDF; Lipson will be speaking at Thrilling Wonder Stories 3 at Studio-X NYC].

Then, Saturday, October 29th, everything comes to a close with an epic second day—from 2-7pm—at Studio-X NYC, featuring:

JAMES FLEMING

Historian and author of Fixing The Sky: The Checkered History of Weather and Climate Control

MARC KAUFMAN

Science writer for the Washington Post and author of First Contact: Scientific Breakthroughs in the Hunt for Life Beyond Earth

ANDREW BLUM

Journalist and author of Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet

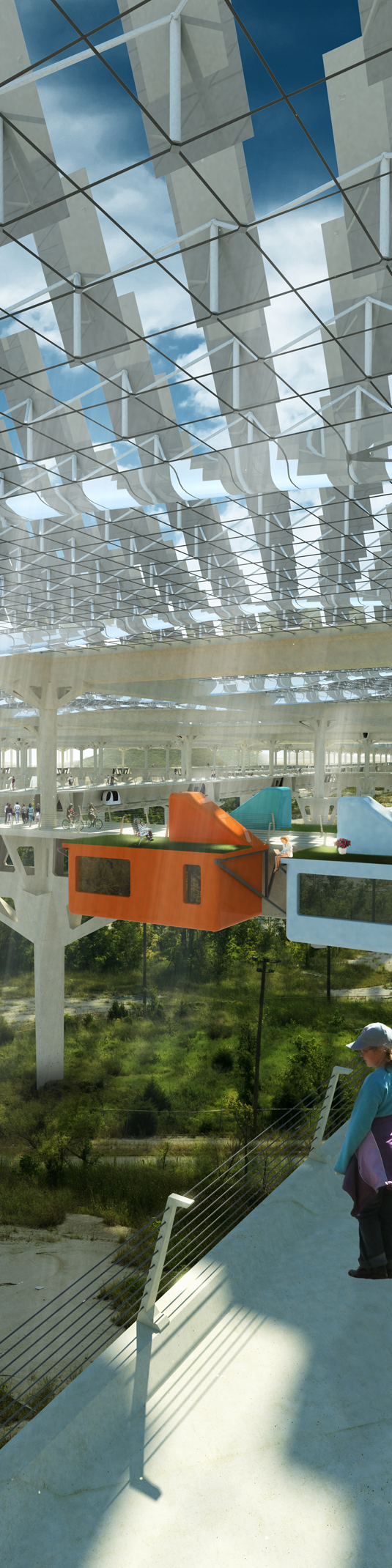

DAVID BENJAMIN

Architect and co-director of The Living

DEBBIE CHACHRA

Researcher and educator in biological materials and engineering design, featured in Wired UK‘s 2010 “Year In Ideas”

HOD LIPSON

Researcher in evolutionary robotics and the future of 3D printing at Cornell University

CARLOS OLGUIN

Designer at Autodesk Research working on the intersection of bio-nanotechnology and 3D visualization

CHRIS WOEBKEN

Interaction designer

SIMONE FERRACINA

Architect, winner of the 2011 Animal Architecture Awards, and author of Organs Everywhere

DAVE GRACER

Insect agriculturalist at Small Stock Foods

MORRIS BENJAMINSON

Bioengineer of in-vitro edible muscle protein and CEO of Zymotech Enterprises

ANDREW HESSEL

Science writer and open-source biologist, focusing on bacterial genomics

The events in New York will be moderated by myself, Studio-X NYC co-director Nicola Twilley, and PopSci senior associate editor Ryan Bradley. In both locations, events are free and open to the public; however, if you plan on attending the Studio-X NYC event, please register as limited space will be available. Here’s a map.

[Image: The “plastic” extruded by New England’s Colletes inaequalis bees; photo by Debbie Chachra].

[Image: The “plastic” extruded by New England’s Colletes inaequalis bees; photo by Debbie Chachra].

Finally, if you can’t make it in person, consider following Thrilling Wonder Stories on Twitter—and keep your eye out at the end of summer 2012, for the Thrilling Wonder Stories book, published by the Architectural Association.

But I hope to see some of you there!

*Vincenzo Natali will be speaking via Skype.

[Image: “Meelas Yadee” (2005-2006) by Lamya Gargash].

[Image: “Meelas Yadee” (2005-2006) by Lamya Gargash]. [Image: “Fatima’s Kitchen Cupboard” (2005-2006) by Lamya Gargash].

[Image: “Fatima’s Kitchen Cupboard” (2005-2006) by Lamya Gargash].

[Images: (top) “Blue Purple Chair” (2005-2006) and (bottom) “The Staircase” (2005-2006) by Lamya Gargash].

[Images: (top) “Blue Purple Chair” (2005-2006) and (bottom) “The Staircase” (2005-2006) by Lamya Gargash]. [Image: “Mona Lisa” (2005-2006) by Lamya Gargash].

[Image: “Mona Lisa” (2005-2006) by Lamya Gargash].

Since 2009, an annual

Since 2009, an annual

[Images: Photos from

[Images: Photos from  [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: “Glass Weed” from

[Image: “Glass Weed” from  [Image: One of many evolutionary robotic research projects by Hod Lipson, featured in this

[Image: One of many evolutionary robotic research projects by Hod Lipson, featured in this  [Image: The “plastic” extruded by New England’s Colletes inaequalis bees; photo by Debbie Chachra].

[Image: The “plastic” extruded by New England’s Colletes inaequalis bees; photo by Debbie Chachra].

[Image: The GroundBot system by

[Image: The GroundBot system by  [Image: The GroundBot system by

[Image: The GroundBot system by

[Images: The GroundBot system by

[Images: The GroundBot system by

[Image: The “

[Image: The “

[Image: The Blue Angels create their own cloud systems over the San Francisco Bay;

[Image: The Blue Angels create their own cloud systems over the San Francisco Bay;  [Image: The literary medium of clouds: J.G. Ballard’s “

[Image: The literary medium of clouds: J.G. Ballard’s “

[Image: The weird artificial geology of “soil equivalent” landfill foam; image courtesy of the

[Image: The weird artificial geology of “soil equivalent” landfill foam; image courtesy of the  [Image: Applying “soil equivalent” landfill foam; image courtesy of the

[Image: Applying “soil equivalent” landfill foam; image courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: The rock in question; photo by Monica Almeida, courtesy of the

[Image: The rock in question; photo by Monica Almeida, courtesy of the  [Image: Photo by Monica Almeida, courtesy of the

[Image: Photo by Monica Almeida, courtesy of the

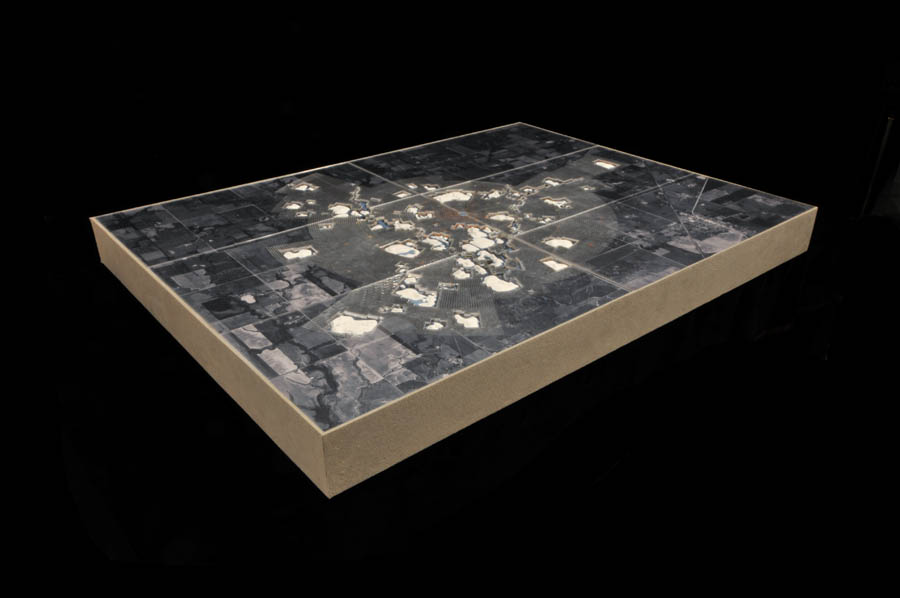

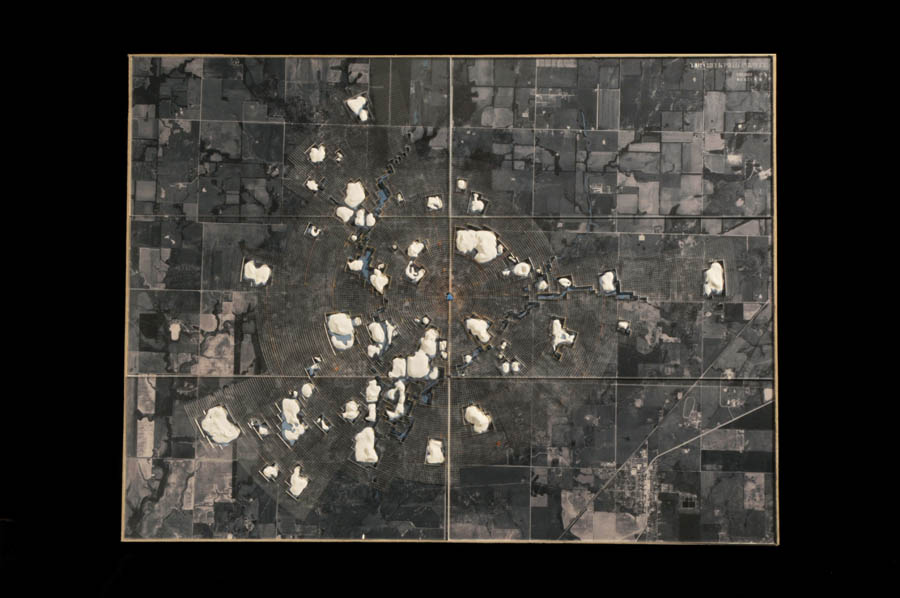

[Image: Inside the Picher, Oklahoma, supergrid, by Clint Langevin and Amy Norris].

[Image: Inside the Picher, Oklahoma, supergrid, by Clint Langevin and Amy Norris].

[Images: Photos of waste rock piles in Picher; (top)

[Images: Photos of waste rock piles in Picher; (top)  [Image: The “kit of parts”].

[Image: The “kit of parts”].

[Images: A wanderer above the sea of white cubes gazes at the Picher supergrid].

[Images: A wanderer above the sea of white cubes gazes at the Picher supergrid].

[Images: More views inside the supergrid; second image is simply a detail from the first (

[Images: More views inside the supergrid; second image is simply a detail from the first (

[Images: The model, by

[Images: The model, by

[Image: Singapore expands beneath the Pacific Ocean; via the

[Image: Singapore expands beneath the Pacific Ocean; via the

[Images: Singapore expands beneath the Pacific Ocean; via the

[Images: Singapore expands beneath the Pacific Ocean; via the

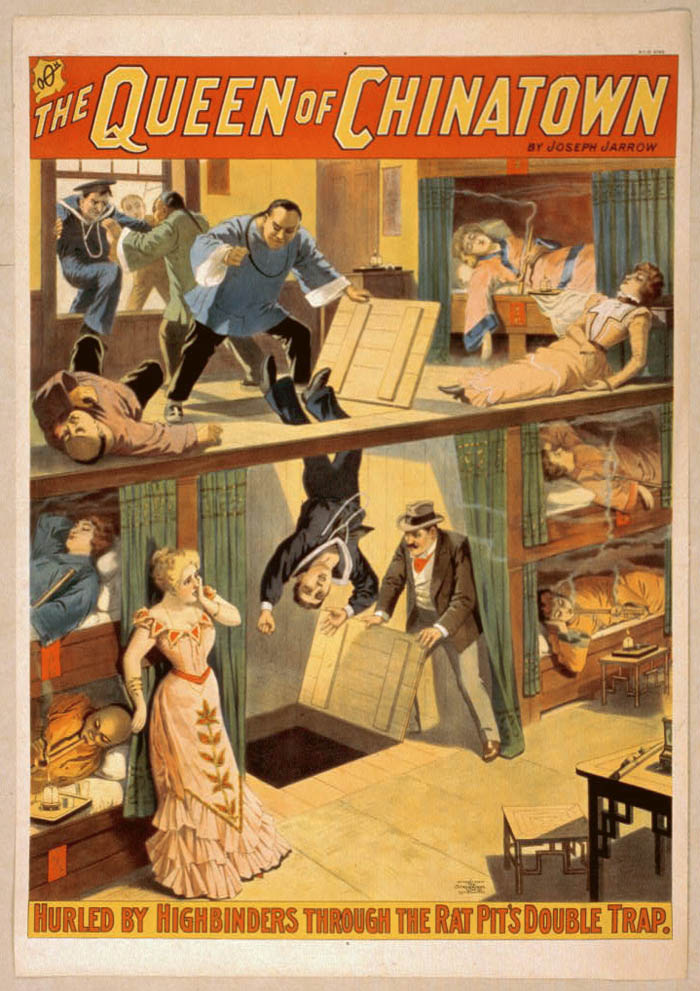

[Image: Poster for “The Queen of Chinatown” by Joseph Jarrow, courtesy of the

[Image: Poster for “The Queen of Chinatown” by Joseph Jarrow, courtesy of the  [Image: A still from

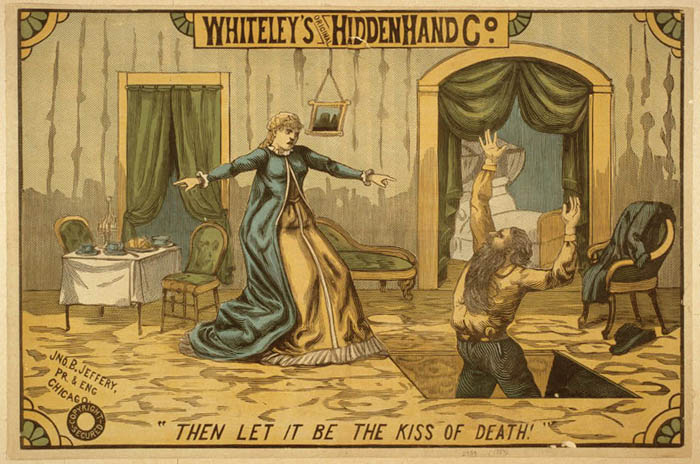

[Image: A still from  [Image: “Then let it be the kiss of death!” Courtesy of the

[Image: “Then let it be the kiss of death!” Courtesy of the