I’m excited to invite everyone to another evening at Studio-X NYC, with photographer Simon Norfolk and journalist Noah Shachtman, who will participate in two back-to-back live interviews discussing new spaces and technologies of conflict in the 21st century.

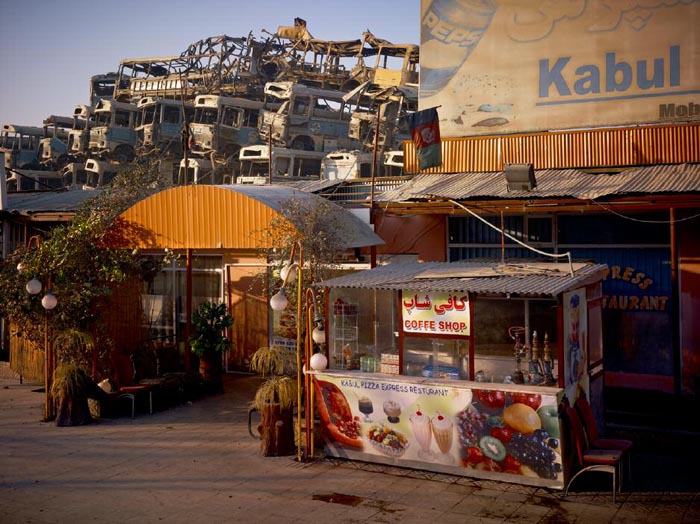

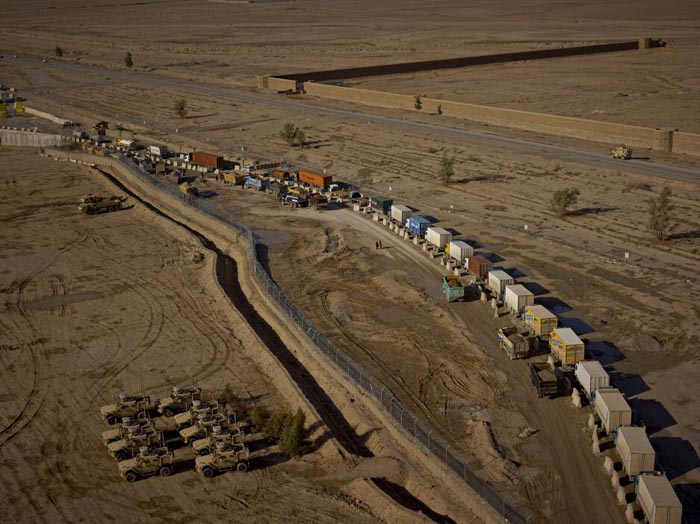

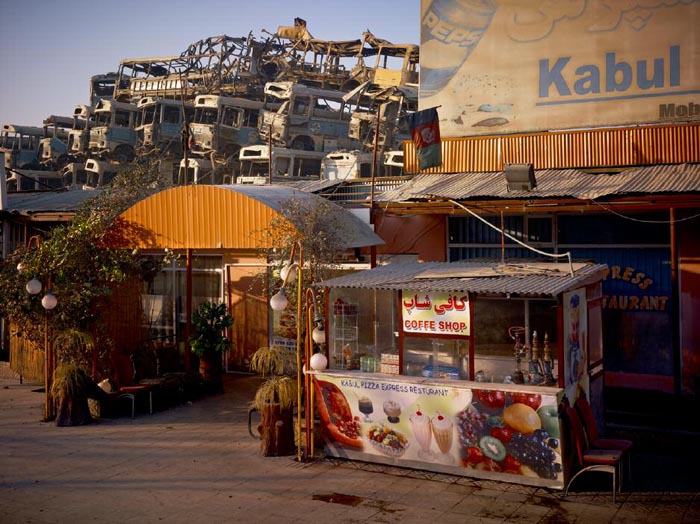

[Image: Photo by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

[Image: Photo by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

Long-term readers of BLDGBLOG will remember Simon Norfolk from his interview here on the site back in 2006.

[Image: Photo by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

[Image: Photo by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

Tuesday’s conversation will revisit many of those same themes, but it will do so in the provocative context of Norfolk’s newest project, a photographic tour of Afghanistan in the footsteps of photographer John Burke:

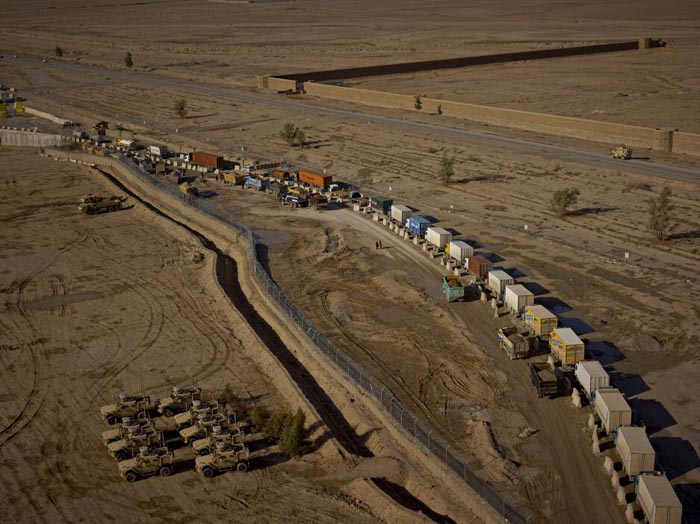

In October 2010, Simon Norfolk began a series of new photographs in Afghanistan, which takes its cue from the work of nineteenth-century British photographer John Burke. Norfolk’s photographs reimagine or respond to Burke’s Afghan war scenes in the context of the contemporary conflict. Conceived as a collaborative project with Burke across time, this new body of work is presented alongside Burke’s original portfolios.

We will take a look not only at the resulting photographs—a selection of which appear here—but at the often overlapping responsibilities of the photojournalist and the artist in documenting political events in conflict zones around the world.

[Image: Photo by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

[Image: Photo by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

As you can see in the photos reproduced here, Norfolk has an eye for complex stratigraphy: where US and UK basecamps overlap with Afghan townscapes, which in turn visually—and politically—repeat earlier scenes from a different era of misbegotten imperial adventures in Central Asia.

It is all simply “a cycle of imperial history,” Norfolk suggests, one in which a “lack of historical perspective on the part of the West allows them to blunder back for the fourth time thinking that you can turn Afghans into western liberal democrats and feminists by bombing them.” Norfolk doesn’t mince words: “the prosecution of the war makes me furious,” he explains in a long conversation hosted on his website.

[Images: Photos by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

[Images: Photos by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

Noah Shachtman‘s reputation as a journalist and editor has been firmly solidified over nearly a decade. Beginning with DefenseTech, a site Shachtman founded in 2003, and continuing with the current reign of Wired’s Danger Room, Shachtman has been prolific, engaged, and highly active in helping to set the agenda for national defense coverage in the post-9/11 world.

[Images: Photos by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

[Images: Photos by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

We’ll be asking Shachtman about everything from the limits of the battlefield—where war chaotically begins and unclearly ends—to new technologies of surveillance, and from the strategic requirements of a journalist covering today’s sites of conflict to the possible urban futures Shachtman might detect in current military headlines.

[Images: Photos by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

[Images: Photos by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

I’m genuinely looking forward to this, and hope to see many of you there. The format will be as follows. From 6:30pm to shortly after 7pm, we will be engaging with Simon Norfolk in a live interview about his work; then, till roughly 7:40pm, we will be interviewing Noah Shachtman. These will be stand-alone interviews, conducted back-to-back.

The final stretch of the night, from 7:45 to 8:30pm or so, will be an open conversation with both Norfolk and Shachtman, featuring questions from anyone who might have them. This will allow us to discuss similarities and differences between their work, and to tease out other themes that might have been passed over in the individual interviews.

[Image: Photo by John Burke, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan by Simon Norfolk].

[Image: Photo by John Burke, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan by Simon Norfolk].

Unfortunately, I have to ask that you RSVP to studioxnyc [at] gmail [dot] com if you plan to attend. Otherwise, the event is free and open to the public.

You will find us at 180 Varick Street, Suite 1610, in Manhattan. Here is a map.

[Images: Photos by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

[Images: Photos by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

Meanwhile, please feel free to go back through BLDGBLOG’s interview with Simon Norfolk in full—it’s one of my personal favorites on the site, and is a great read—and to click through Noah Shachtman’s own website, including the overall resources of Danger Room.

[Image: Photo by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

[Image: Photo by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

As Norfolk says in the BLDGBLOG interview, and which perhaps serves as a useful conceptual umbrella for the entire forthcoming evening:

All of the work that I’ve been doing over the last five years is about warfare and the way war makes the world we live in. War shapes and designs our society. The landscapes that I look at are created by warfare and conflict. This is particularly true in Europe. I went to the city of Cologne, for instance, and the city of Cologne was built by Charlemagne—but Cologne has the shape that it does today because of the abilities and non-abilities of a Lancaster Bomber. It comes from what a Lancaster can do and what a Lancaster can’t do. What it cannot do is fly deep into Germany in the middle of the day and pinpoint-bomb a ball bearing factory. What it can do is fly to places that are quite near to England, that are five miles across, on a bend in the river, under moonlight, and then hit them with large amounts of H.E.. And if you do that, you end up with a city that looks like Cologne—the way the city’s shaped.

So I started off in Afghanistan photographing literal battlefields—but I’m trying to stretch that idea of what a battlefield is. Because all the interesting money now—the new money, the exciting stuff—is about entirely new realms of warfare: inside cyberspace, inside parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. Eavesdropping, intelligence, satellite warfare, imaging—this is where all the exciting stuff is going to happen in twenty years’ time. So I wanted to stretch that idea of what a battleground could be. What is a landscape—a surface, an environment, a space—created by warfare?

I hope to see you at 6:30pm on Tuesday, September 13th.

[Image: Photo by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

[Image: Photo by Simon Norfolk, from Burke + Norfolk: Photographs from the War in Afghanistan].

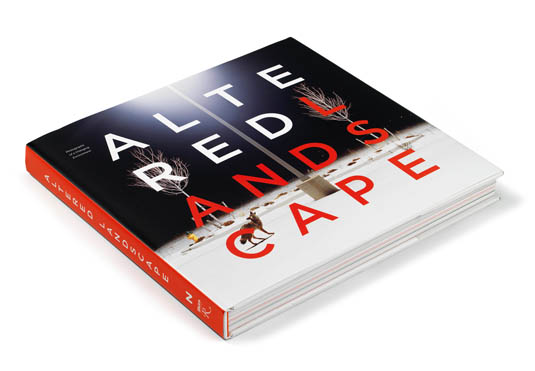

[Image: The Altered Landscape: Photographs of a Changing Environment edited by Ann M. Wolfe].

[Image: The Altered Landscape: Photographs of a Changing Environment edited by Ann M. Wolfe]. [Image: “Howl” (2007) by Amy Stein; from The Altered Landscape edited by Ann M. Wolfe].

[Image: “Howl” (2007) by Amy Stein; from The Altered Landscape edited by Ann M. Wolfe]. [Image: “Coolidge Dam, San Carlos, AZ” (1997) by Toshio Shibata; from The Altered Landscape edited by Ann M. Wolfe].

[Image: “Coolidge Dam, San Carlos, AZ” (1997) by Toshio Shibata; from The Altered Landscape edited by Ann M. Wolfe].

[Image: From an Air Force Research Laboratory presentation on “Robotics: Research and Development”].

[Image: From an Air Force Research Laboratory presentation on “Robotics: Research and Development”]. [Image: “A U.S. Air Force F-22A Raptor Stealth Fighter Jet Executes A Maneuver Through A Cloud Of Vapor”—that is, it tunnels through the sky—”At The 42nd Naval Base Ventura County Air Show, April 1, 2007, Point Mugu, State of California, USA”; photo by Technical Sgt. Alex Koenig,

[Image: “A U.S. Air Force F-22A Raptor Stealth Fighter Jet Executes A Maneuver Through A Cloud Of Vapor”—that is, it tunnels through the sky—”At The 42nd Naval Base Ventura County Air Show, April 1, 2007, Point Mugu, State of California, USA”; photo by Technical Sgt. Alex Koenig,

[Image: The

[Image: The

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: Landform Building launch at the

[Image: Landform Building launch at the

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: Photo by John Burke, from

[Image: Photo by John Burke, from

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: A ghostlike “sonographic image” taken from part of Mark Bain’s

[Image: A ghostlike “sonographic image” taken from part of Mark Bain’s

[Images: The global road salt trade, mapped by

[Images: The global road salt trade, mapped by

[Image:

[Image:

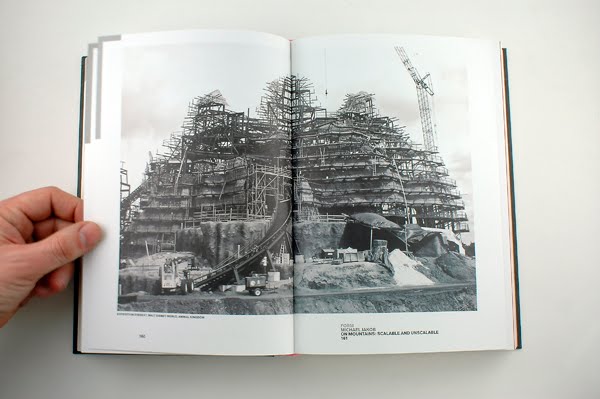

[Images: Spreads from

[Images: Spreads from

[Images: Window and floor diagrams in place for tomorrow’s launch of

[Images: Window and floor diagrams in place for tomorrow’s launch of

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of

[Image: An otherwise unrelated photo of

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: Album design by Gerco Hiddink for

[Image: Album design by Gerco Hiddink for  [Image: “

[Image: “