Tim Maly of Quiet Babylon and Nicola Twilley of Edible Geography have both jumped into the Glacier/Island/Storm blogathon unfolding this week with posts about, respectively, questions of island sovereignty, national borders, data havens, geo-preservation and more, and, at Edible Geography, specialty ices developed for the boutique cocktail trade.

[Image: The Okinotori Islands—or are they reefs? Image via Tim Maly].

[Image: The Okinotori Islands—or are they reefs? Image via Tim Maly].

Tim’s post—which you should read in full—brings to mind recent moves by the Australian government to “excise” distant islands so as to prevent illegal immigrants from reaching what would otherwise legally recognized as Australian land.

The whole legislative exercise falls somewhere between a managed retreat of territorial sovereignty and a particularly Kafka-esque interpretation of Zeno’s paradox.

In Kafka’s short story “A Message from the Emperor,” for instance, we read that an imperial messenger, instructed to deliver the dying emperor’s final wish to a recipient far away, finds himself unable to travel anywhere at all. Indeed, as he struggles to make his way through endless crowds and palace antechambers, fighting his way toward a destination that was, at best, unclear, “how futile are all his efforts,” we read.

He is still forcing his way through the private rooms of the innermost palace. Never will he win his way through. And if he did manage that, nothing would have been achieved. He would have to fight his way down the steps, and, if he managed to do that, nothing would have been achieved. He would have to stride through the courtyards, and after the courtyards through the second palace encircling the first, and, then again, through stairs and courtyards, and then, once again, a palace, and so on for thousands of years.

Now reverse this. Imagine someone—a subject of the empire—trying to force his or her way back to the center, trying against overwhelming odds to reach the very epicenter of sovereign power, but utterly unable to succeed.

There is always another courtyard to cross; always more rooms to run through.

Now imagine this being played out on a South Pacific archipelago, where you are up against a sovereign state that insists on “excising” bits and bobs of its outer territory in order to sabotage your own best efforts to get somewhere. You step onto one island, secure in what you think is arrival, only to be told that, no, this is not yet Australia. You are both here and not here. This island is us—but it is also something we have legally abandoned.

So you move on to the next island—and the next, and the next.

The territorial complexities of sovereign governance thus rapidly spiral into clouds of uncertainty.

[Image: Map of Christmas Island].

[Image: Map of Christmas Island].

According to The Age, an Australian newspaper, “the Howard government removed about 4,600 islands from the migration zone in 2005, preventing boat people who land there from accessing Australian law and claiming asylum in Australia.” The “migration zone” referred to here includes Christmas Island, which now—in 2010—falls into a strange grey zone of legality; from the perspective of an arriving immigrant, it both is and is not Australia.

This is what architect Ed Keller might call the political science fiction of excised island terrain.

I’m reminded of China Miéville’s recent novel The City & The City, in which differently controlled but spatially overlapping urban territories have been marbled into and through one another; you can physically stand in two cities at once, yet only legally be present in one at any given time.

Now blow Miéville’s strange in-and-out status up to the scale of a South Pacific archipelago and you have something approximating the spatial logic of Australian territorial law as applied to commonly used immigration routes.

Read the actual, island-excising Parliamentary documentation here.

[Image: Photo by Melissa Hom for New York Magazine].

[Image: Photo by Melissa Hom for New York Magazine].

Nicola Twilley, meanwhile, studies “detailed instructions for artificial glacier construction,” suggesting that “vernacular Himalayan glacier grafting techniques” might actually “have the potential to revolutionize the cocktails of tomorrow.”

In other words, artificial glaciers grown and maintained by specialty cocktail bars could be produced to order, made to include “orchid flowers, raspberries, or espresso beans,” Nicola writes, thus creating “flavor-accented glaciers.” These could then be chopped down into “berry-studded chunks,” rough cubes that supply “the perfect finishing touch for a Brownie Cognac or Irish coffee.”

“The theatrical potential of custom artificial glaciers,” she jokes, “might be second only to the champagne fountain.”

[Images: Photos by Melissa Hom for New York Magazine].

[Images: Photos by Melissa Hom for New York Magazine].

These are only the two most recent posts in a week full of linked conversations exploring the Glacier/Island/Storm studio at Columbia University. Here is a list of those relevant posts, if you’re interested:

Edible Geography: The Ice Program

Quiet Babylon: Islands in the Net

BLDGBLOG: Vincent Van Gogh and the Storm Archive

BLDGBLOG: Geothermal Gardens and the Hot Zones of the City

mammoth, a glacier is a very long event

InfraNet Lab, LandFab, or Manufacturing Terrain

Nick Sowers, Design to Fail

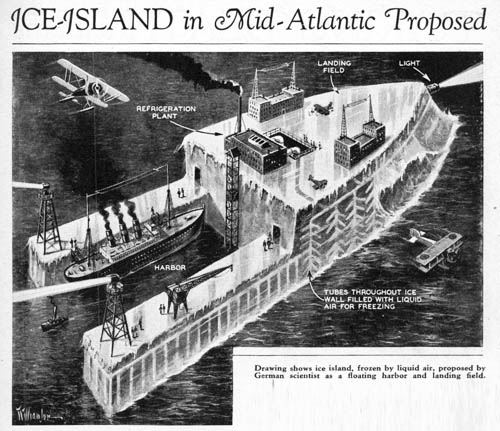

[Image: “Drawing shows ice island, frozen by liquid air, proposed by German scientist as a floating harbor and landing field”; via InfraNet Lab].

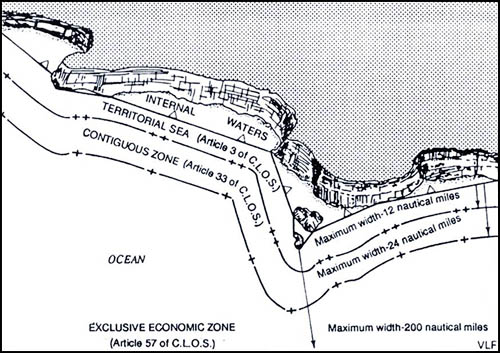

[Image: “Drawing shows ice island, frozen by liquid air, proposed by German scientist as a floating harbor and landing field”; via InfraNet Lab]. [Image: Map showing a straight baseline separating internal waters from zones of maritime jurisdiction; via

[Image: Map showing a straight baseline separating internal waters from zones of maritime jurisdiction; via  [Image: Photo by Andy Marshall of

[Image: Photo by Andy Marshall of  [Image: Perseids Meteor Shower, August 11, 1999; photo by Wally Pacholka, courtesy of

[Image: Perseids Meteor Shower, August 11, 1999; photo by Wally Pacholka, courtesy of  [Image: Halley’s Comet—upper right—passes through the

[Image: Halley’s Comet—upper right—passes through the  [Image: Rock art possibly depicting a supernova. Photo by John Barentine, Apache Point Observatory, courtesy of

[Image: Rock art possibly depicting a supernova. Photo by John Barentine, Apache Point Observatory, courtesy of  [Image: Courtesy of Flickr-user

[Image: Courtesy of Flickr-user  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: The Okinotori Islands—or

[Image: The Okinotori Islands—or  [Image: Map of

[Image: Map of  [Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Images: Photos by

[Images: Photos by  [Image: Vincent Van Gogh, “

[Image: Vincent Van Gogh, “ [Image: Vincent Van Gogh, “

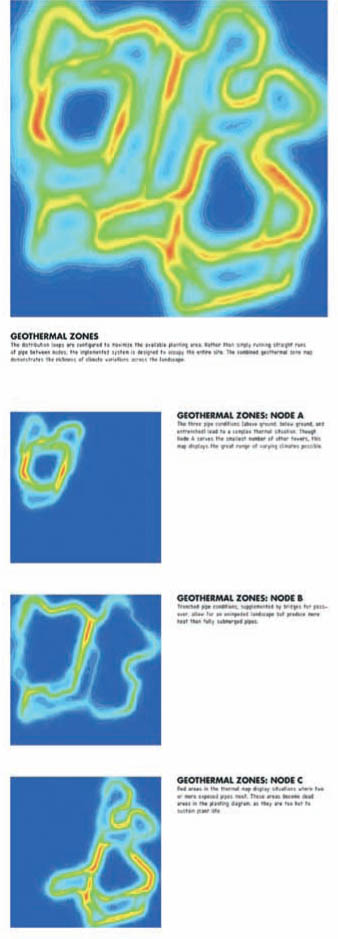

[Image: Vincent Van Gogh, “ [Image: “Reykjavik Botanical Garden” by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

[Image: “Reykjavik Botanical Garden” by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr]. [Image: “Reykjavik Botanical Garden” by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

[Image: “Reykjavik Botanical Garden” by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr]. [Image: “Reykjavik Botanical Garden” by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr].

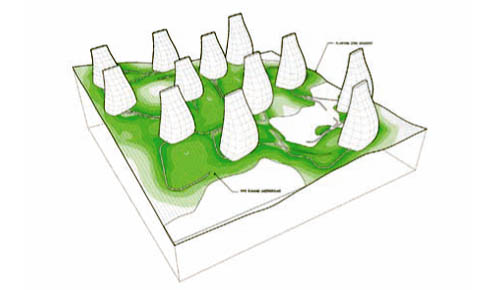

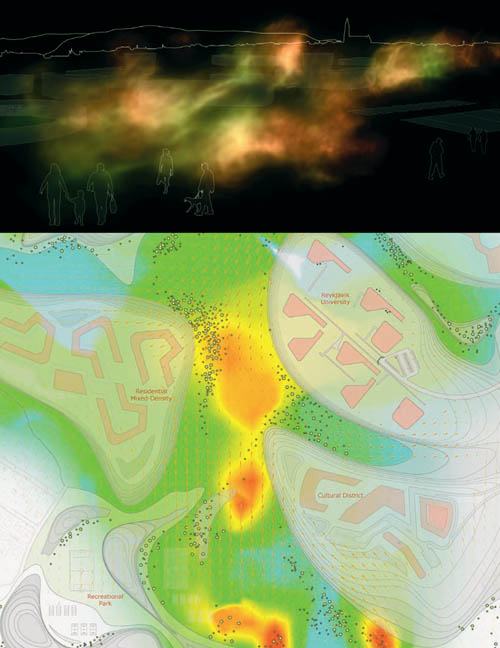

[Image: “Reykjavik Botanical Garden” by Andrew Corrigan and John Carr]. [Image: Produced for the “Vatnsmyri Urban Planning Competition” by Sean Lally, Andrew Corrigan, and Paul Kweton of

[Image: Produced for the “Vatnsmyri Urban Planning Competition” by Sean Lally, Andrew Corrigan, and Paul Kweton of  [Image: Glacier-protection services in the Swiss Alps; photo by Olivier Maire/Epa/Corbis, via the

[Image: Glacier-protection services in the Swiss Alps; photo by Olivier Maire/Epa/Corbis, via the  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From