[Image: The Very Low Frequency antenna field at Cutler, Maine, a facility for communicating with at-sea submarine crews].

[Image: The Very Low Frequency antenna field at Cutler, Maine, a facility for communicating with at-sea submarine crews].

There have been about a million stories over the past few weeks that I’ve been dying to write about, but I’ll just have to clear through a bunch here in one go.

1) First up is a fascinating request for proposals from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, who is looking to build a “Positioning System for Deep Ocean Navigation.” It has the handy acronym of POSYDON.

POSYDON will be “an undersea system that provides omnipresent, robust positioning” in the deep ocean either for crewed submarines or for autonomous seacraft. “DARPA envisions that the POSYDON program will distribute a small number of acoustic sources, analogous to GPS satellites, around an ocean basin,” but I imagine there is some room for creative maneuvering there.

The idea of an acoustic deep-sea positioning system that operates similar to GPS is pretty interesting to imagine, especially considering the strange transformations sound undergoes as it is transmitted through water. To establish accurately that a U.S. submarine has, in fact, heard an acoustic beacon and that its apparent distance from that point is not being distorted by intervening water temperature, ocean currents, or even the large-scale presence of marine life is obviously quite an extraordinary challenge.

As DARPA points out, without such a system in place, “undersea vehicles must regularly surface to receive GPS signals and fix their position, and this presents a risk of detection.” The ultimate goal, then, would be to launch ultra-longterm undersea missions, even establish permanently submerged robotic networks that have no need to breach the ocean’s surface. Cthulhoid, they will forever roam the deep.

[Image: An unmanned underwater vehicle; U.S. Navy photo by S. L. Standifird].

[Image: An unmanned underwater vehicle; U.S. Navy photo by S. L. Standifird].

If you think you’ve got what it takes, click over to DARPA and sign up.

2) A while back, I downloaded a free academic copy of a fascinating book called Space-Time Reference Systems by Michael Soffel and Ralf Langhans.

Their book “presents an introduction to the problem of astronomical–geodetical space–time reference systems,” or radically offworld navigation reference points for when a craft is, in effect, well beyond any known or recognizable landmarks in space. Think of it as a kind of new longitude problem.

The book is filled with atomic clocks, quasars potentially repurposed as deep-space orientation beacons, the long-term shifting of “astronomical reference frames,” and page after page of complex math I make no claim to understand.

However, I mention this here because the POSYDON program is almost the becoming-cosmic of the ocean: that is, the depths of the sea reimagined as a vast and undifferentiated space within which mostly robotic craft will have to orient themselves on long missions. For a robotic submarine, the ocean is its universe.

3) The POSYDON program is just one part of a much larger militarization of the deep seas. Consider the fact that the U.S. Office of Naval Research is hoping to construct permanent “hubs” on the seafloor for recharging robot submarines.

These “hubs” would be “unmanned, underwater pods where robots can recharge undetected—and securely upload the intelligence they’ve gathered to Navy networks.” Hubs will be places where “unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) can dock, recharge, upload data and download new orders, and then be on their way.”

“You could keep this continuous swarm of UUVs [Unmanned Underwater Vehicles] wherever you wanted to put them… basically indefinitely, as long as you’re rotating (some) out periodically for mechanical issues,” a Naval war theorist explained to Breaking Defense.

The ultimate vision is a kind of planet-spanning robot constellation: “The era of lone-wolf submarines is giving away [sic] to underwater networks of manned subs, UUVs combined with seafloor infrastructure such as hidden missile launchers—all connected to each other and to the rest of the force on the surface of the water, in the air, in space, and on land.” This would include, for example, the “upward falling payloads” program described on BLDGBLOG a few years back.

Even better, from a military communications perspective, these hubs would also act as underwater relay points for broadcasting information through the water—or what we might call the ocean as telecommunications medium—something that currently relies on ultra-low frequency radio.

There is much more detail on this over at Breaking Defense.

4) Last summer, my wife and I took a quick trip up to Maine where we decided to follow a slight detour after hiking Mount Katahdin to drive by the huge antenna field at Cutler, a Naval communications station found way out on a tiny peninsula nearly on the border with Canada.

[Image: The antenna field at Cutler, Maine].

[Image: The antenna field at Cutler, Maine].

We talked to the security guard for a while about life out there on this little peninsula, but we were unable to get a tour of the actual facility, sadly. He mostly joked that the locals have a lot of conspiracy theories about what the towers are actually up to, including their potential health effects—which isn’t entirely surprising, to be honest, considering the massive amounts of energy used there and the frankly otherworldly profile these antennas have on the horizon—but you can find a lot of information about the facility online.

So what does this thing do? “The Navy’s very-low-frequency (VLF) station at Cutler, Maine, provides communication to the United States strategic submarine forces,” a January 1998 white paper called “Technical Report 1761” explains. It is basically an east coast version of the so-called Project Sanguine, a U.S. Navy program from the 1980s that “would have involved 41 percent of Wisconsin,” turning the Cheese State into a giant military antenna.

So what does this thing do? “The Navy’s very-low-frequency (VLF) station at Cutler, Maine, provides communication to the United States strategic submarine forces,” a January 1998 white paper called “Technical Report 1761” explains. It is basically an east coast version of the so-called Project Sanguine, a U.S. Navy program from the 1980s that “would have involved 41 percent of Wisconsin,” turning the Cheese State into a giant military antenna.

Cutler’s role in communicating with submarines may or may not have come to an end, making it more of a research facility today, but the idea that, even if this came to an end with the Cold War, isolated radio technicians on a foggy peninsula in Maine were up there broadcasting silent messages into the ocean that were meant to be heard only by U.S. submarine crews pinging around in the deepest canyons of the Atlantic is both poetic and eerie.

[Image: A diagram of the antennas, from the aforementioned January 1998 research paper].

[Image: A diagram of the antennas, from the aforementioned January 1998 research paper].

The towers themselves are truly massive, and you can easily see them from nearby roads, if you happen to be anywhere near Cutler, Maine.

In any case, I mention all this because behemoth facilities such as these could be made altogether redundant by autonomous underwater communication hubs, such as those described by Breaking Defense.

5) “The robots are winning!” Daniel Mendelsohn wrote in The New York Review of Books earlier this month. The opening paragraphs of his essay are is awesome, and I wish I could just republish the whole thing:

We have been dreaming of robots since Homer. In Book 18 of the Iliad, Achilles’ mother, the nymph Thetis, wants to order a new suit of armor for her son, and so she pays a visit to the Olympian atelier of the blacksmith-god Hephaestus, whom she finds hard at work on a series of automata:

…He was crafting twenty tripods

to stand along the walls of his well-built manse,

affixing golden wheels to the bottom of each one

so they might wheel down on their own [automatoi] to the gods’ assembly

and then return to his house anon: an amazing sight to see.

These are not the only animate household objects to appear in the Homeric epics. In Book 5 of the Iliad we hear that the gates of Olympus swivel on their hinges of their own accord, automatai, to let gods in their chariots in or out, thus anticipating by nearly thirty centuries the automatic garage door. In Book 7 of the Odyssey, Odysseus finds himself the guest of a fabulously wealthy king whose palace includes such conveniences as gold and silver watchdogs, ever alert, never aging. To this class of lifelike but intellectually inert household helpers we might ascribe other automata in the classical tradition. In the Argonautica of Apollonius of Rhodes, a third-century-BC epic about Jason and the Argonauts, a bronze giant called Talos runs three times around the island of Crete each day, protecting Zeus’s beloved Europa: a primitive home alarm system.

Mendelsohn goes on to discuss “the fantasy of mindless, self-propelled helpers that relieve their masters of toil,” and it seems incredibly interesting to read it in the context of DARPA’s now even more aptly named POSYDON program and the permanent undersea hubs of the Office of Naval Research. Click over to The New York Review of Books for the whole thing.

6) If the oceanic is the new cosmic, then perhaps the terrestrial is the new oceanic.

The Independent reported last month that magnetically powered underground robot “moles”—effectively subterranean drones—could potentially be used to ferry objects around beneath the city. They are this generation’s pneumatic tubes.

The idea would be to use “a vast underground network of pipes in a bid to bypass the UK’s ever more congested roads.” The company’s name? What else but Mole Solutions, who refer to their own speculative infrastructure as a network of “freight pipelines.”

[Image: Courtesy of Mole Solutions].

[Image: Courtesy of Mole Solutions].

Taking a page from the Office of Naval Research and DARPA, though, perhaps these subterranean robot constellations could be given “hubs” and terrestrial beacons with which to orient themselves; combine with the bizarre “self-burying robot” from 2013, and declare endless war on the surface of the world from below.

See more at the Independent.

7) Finally, in terms of this specific flurry of links, Denise Garcia looks at the future of robot warfare and the dangerous “secrecy of emerging weaponry” that can act without human intervention over at Foreign Affairs.

She suggests that “nuclear weapons and future lethal autonomous technologies will imperil humanity if governed poorly. They will doom civilization if they’re not governed at all.” On the other hand, as Daniel Mendelsohn points out, we have, in a sense, been dealing with the threat of a robot apocalypse since someone first came up with the myth of Hephaestus.

Garcia’s short essay covers a lot of ground previously seen in, for example, Peter Singer’s excellent book Wired For War; that’s not a reason to skip one for the other, of course, but to read both. See more at Foreign Affairs.

(Thanks to Peter Smith for suggesting we visit the antennas at Cutler).

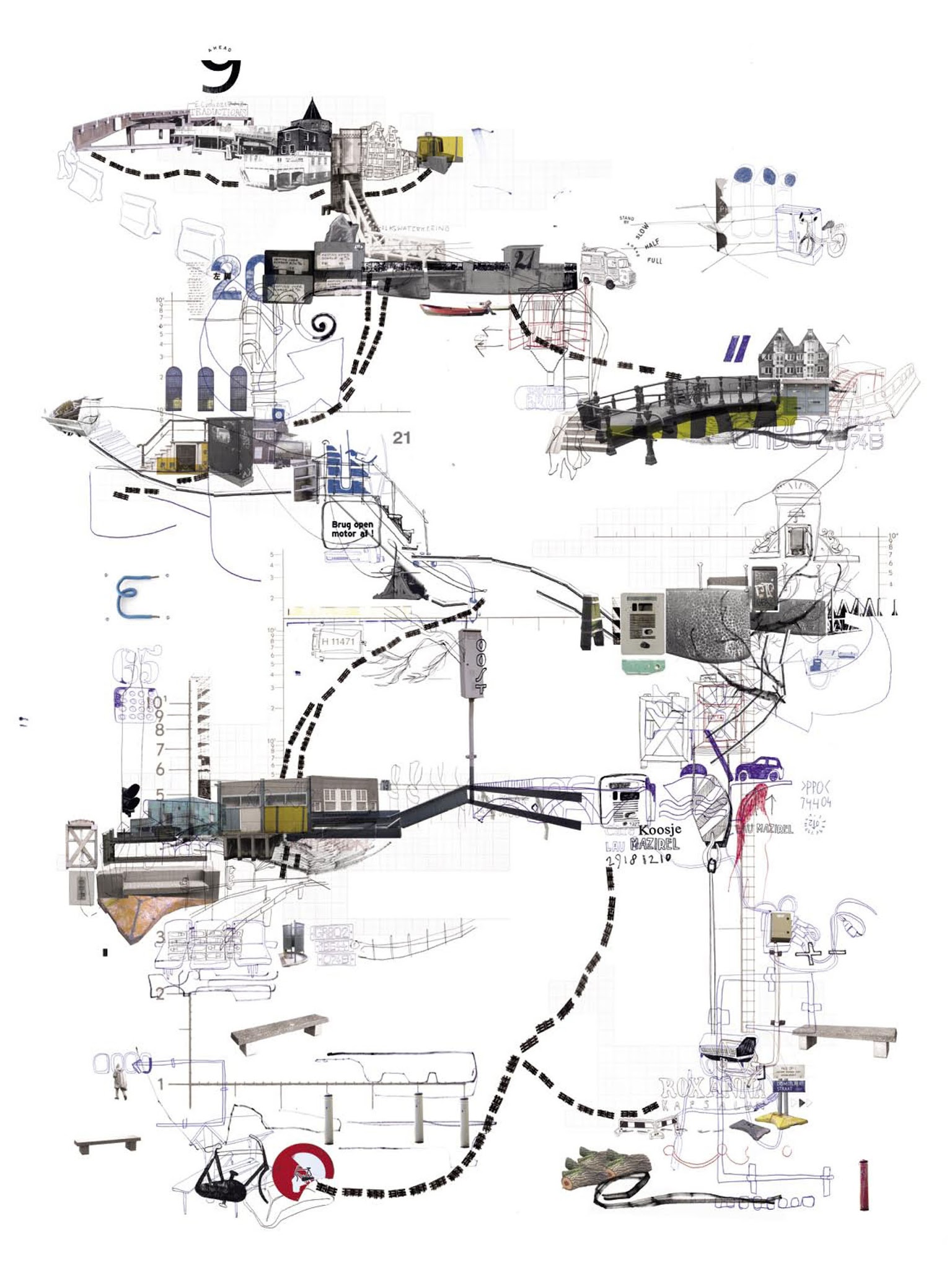

[Image: From Project 360º by Frank Dresmé].

[Image: From Project 360º by Frank Dresmé]. [Image: From Project 360º by Frank Dresmé].

[Image: From Project 360º by Frank Dresmé]. [Image: From Project 360º by Frank Dresmé].

[Image: From Project 360º by Frank Dresmé]. [Image: Exhibiting Project 360º by Frank Dresmé].

[Image: Exhibiting Project 360º by Frank Dresmé].

[Image: Thomas Scholes,

[Image: Thomas Scholes,  [Image: Thomas Scholes,

[Image: Thomas Scholes,  [Image: Thomas Scholes,

[Image: Thomas Scholes,  [Image: Thomas Scholes,

[Image: Thomas Scholes,  [Image: Thomas Scholes,

[Image: Thomas Scholes,

[Images: Thomas Scholes,

[Images: Thomas Scholes,  [Image: Thomas Scholes,

[Image: Thomas Scholes,

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: An unrelated shot of a 19th-century silver mine in Michigan; via the

[Image: An unrelated shot of a 19th-century silver mine in Michigan; via the  [Image: Otherwise unrelated shot of a gold mine in California; via the

[Image: Otherwise unrelated shot of a gold mine in California; via the  [Image: Michael Douglas measures out the exact spot of the buried treasure, near some potted plants in Costco; from

[Image: Michael Douglas measures out the exact spot of the buried treasure, near some potted plants in Costco; from  [Image: The lost river uncovered, Douglas prepares to jump in; from

[Image: The lost river uncovered, Douglas prepares to jump in; from

[Image: The Very Low Frequency antenna field at Cutler, Maine, a facility for communicating with at-sea submarine crews].

[Image: The Very Low Frequency antenna field at Cutler, Maine, a facility for communicating with at-sea submarine crews]. [Image: An unmanned underwater vehicle; U.S. Navy photo by S. L. Standifird].

[Image: An unmanned underwater vehicle; U.S. Navy photo by S. L. Standifird]. [Image: The

[Image: The  So what does this thing do? “The Navy’s very-low-frequency (VLF) station at Cutler, Maine, provides communication to the United States strategic submarine forces,” a January 1998 white paper called “Technical Report 1761” explains. It is basically an east coast version of the so-called

So what does this thing do? “The Navy’s very-low-frequency (VLF) station at Cutler, Maine, provides communication to the United States strategic submarine forces,” a January 1998 white paper called “Technical Report 1761” explains. It is basically an east coast version of the so-called  [Image: A diagram of the antennas, from the aforementioned January 1998 research paper].

[Image: A diagram of the antennas, from the aforementioned January 1998 research paper]. [Image: Courtesy of

[Image: Courtesy of

[Image: A laser scan of the Pantheon, courtesy

[Image: A laser scan of the Pantheon, courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: Courtesy

[Image: Courtesy  [Image: In the ruined basements of architectural simultaneity;

[Image: In the ruined basements of architectural simultaneity;