[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida’s Lightning Research Group].

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida’s Lightning Research Group].

This past winter, I had the pleasure of traveling around south Florida with Smout Allen, Kyle Buchanan, and nearly two dozen students from Unit 11 at the Bartlett School of Architecture.

Florida’s variable terrains—of sink holes, swamps, and eroding beaches—and its Herculean infrastructure, from canals and freeways to theme parks and rocket facilities, served as the narrative backdrop for the many architectural projects ultimately produced by the class (in addition, of course, to the 2012 U.S. Presidential election, the results of which we watched live from the bar of a tropical-themed hotel near Cape Canaveral, next door to Ron Jon).

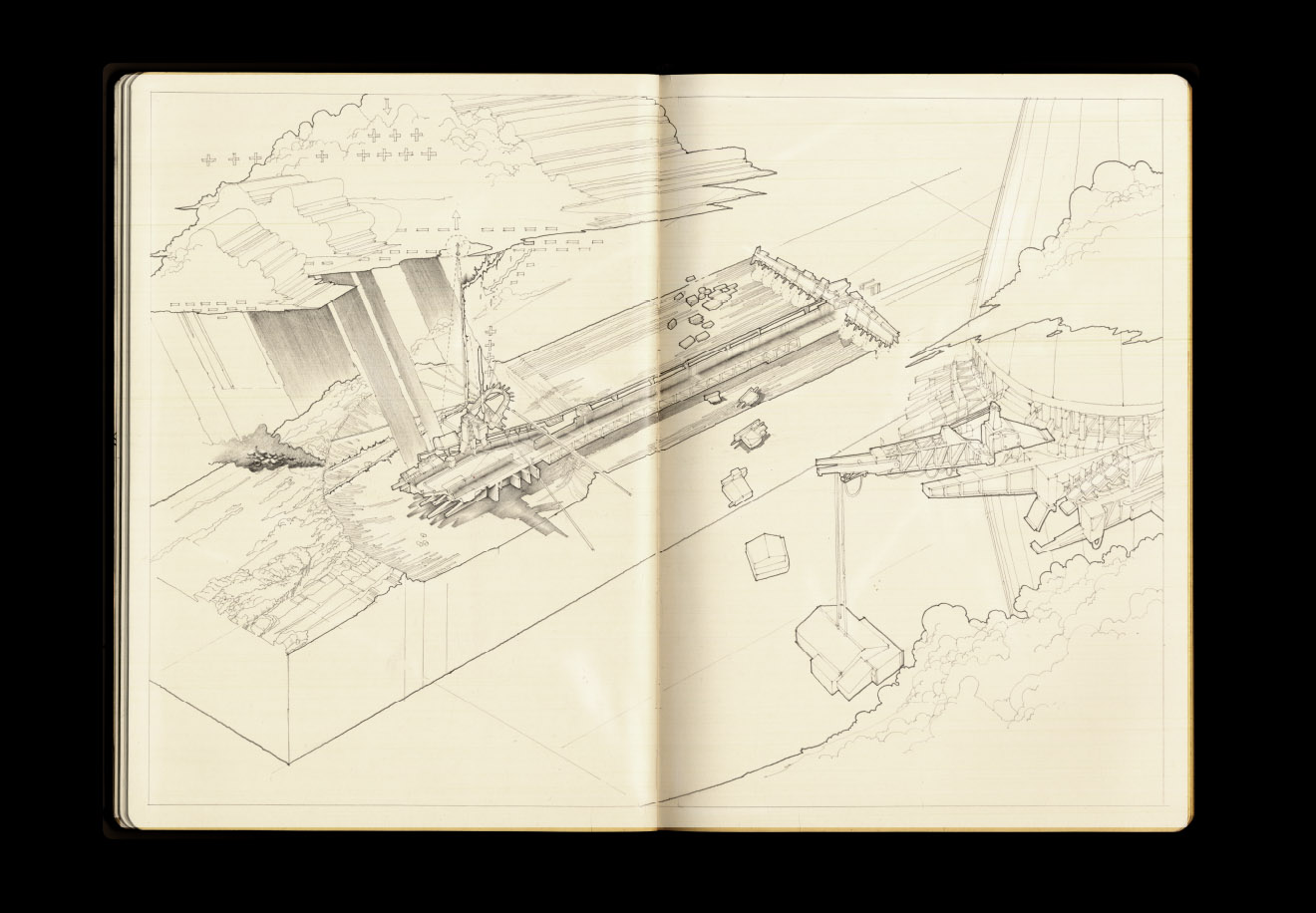

While there were many, many interesting projects resulting from the trip, and from the Unit in general, there is one that I thought I’d post here, by student Farah Aliza Badaruddin, particularly for the quality of its drawings.

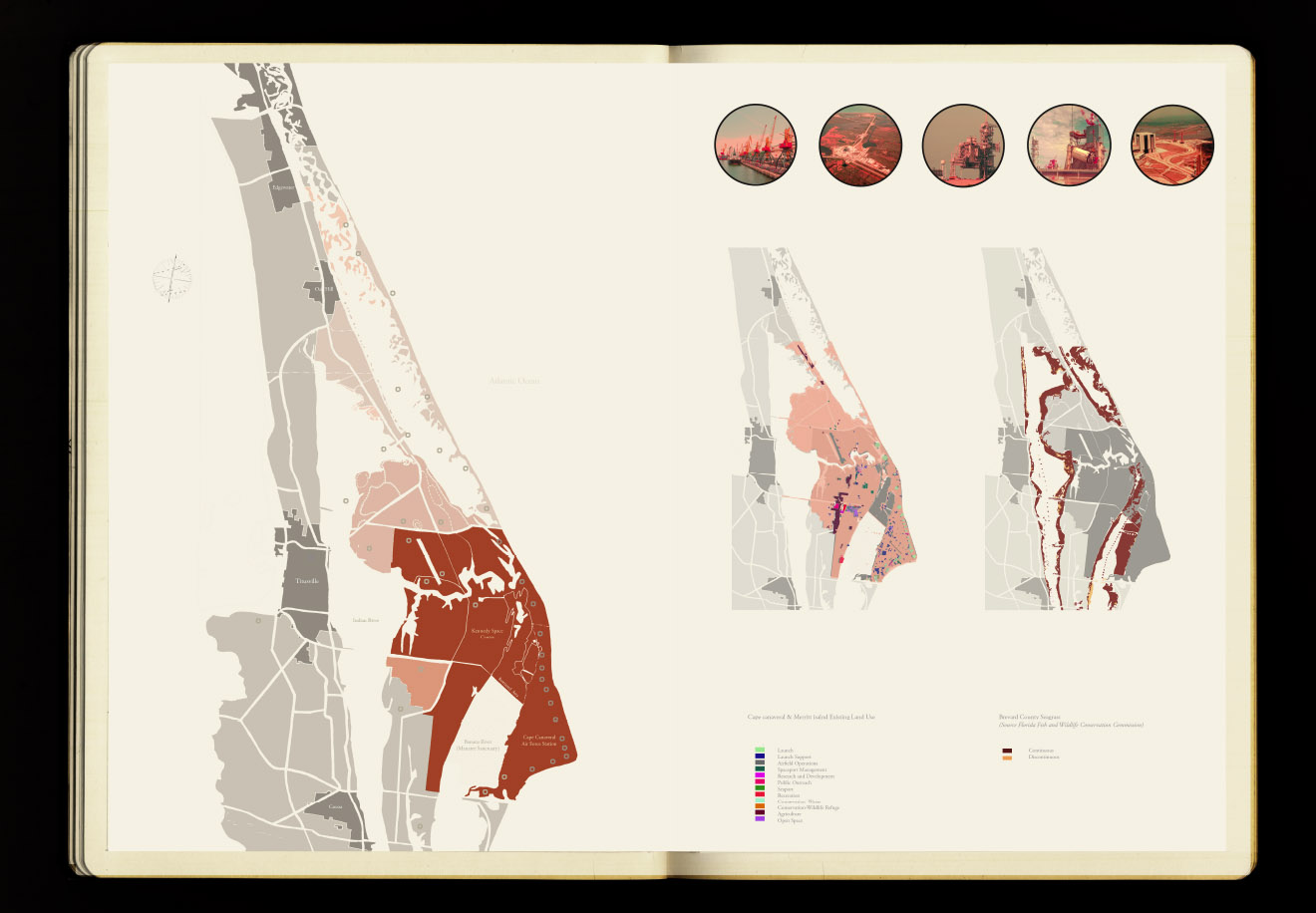

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

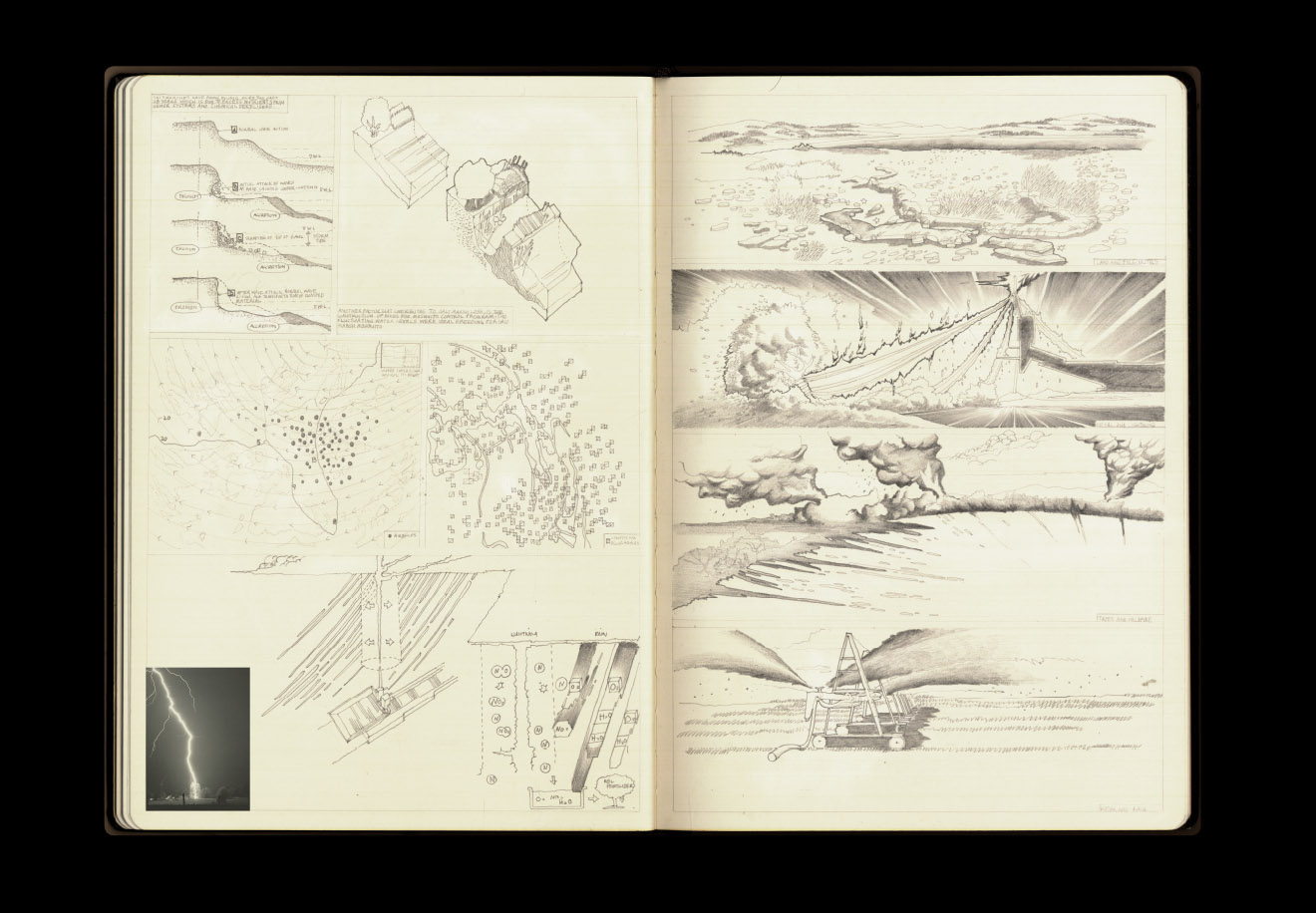

Badaruddin’s project explored the large-scale architectural implications of applying radical weather technologies to the task of landscape remediation, asking specifically if Cape Canaveral’s highly contaminated ground water—polluted by a “viscous toxic goo” made from tens of thousands of pounds of rocket fuels, chemical plumes, solvents, and other industrial waste products over the decades—could be decontaminated through pyrolysis, using guided and controlled bursts of lightning.

In her own words, Badaruddin explains that the would test “the idea that lightning can be harnessed on-site to pyrolyse highly contaminated groundwater as an approach to remediate the polluted site.”

These controlled and repetitive lightning strikes would also, in turn, help fertilize the soil, producing a kind of bio-electro-agricultural event of truly cosmic (or at least Miller-Ureyan) proportions.

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida Lightning Research Group].

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida Lightning Research Group].

Her maps of the area—which she presents as if drawn in a Moleskine notebook—show the terrestrial borders of the proposal (although volumetric maps of the sky, showing the project’s fully three-dimensional engagement with regional weather systems, would have been an equally, if not more, effective way of showing the project’s spatial boundaries).

This raises the awesome question of how you should most accurately represent an architectural project whose central goal is to wield electrical influence on the atmosphere around it.

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

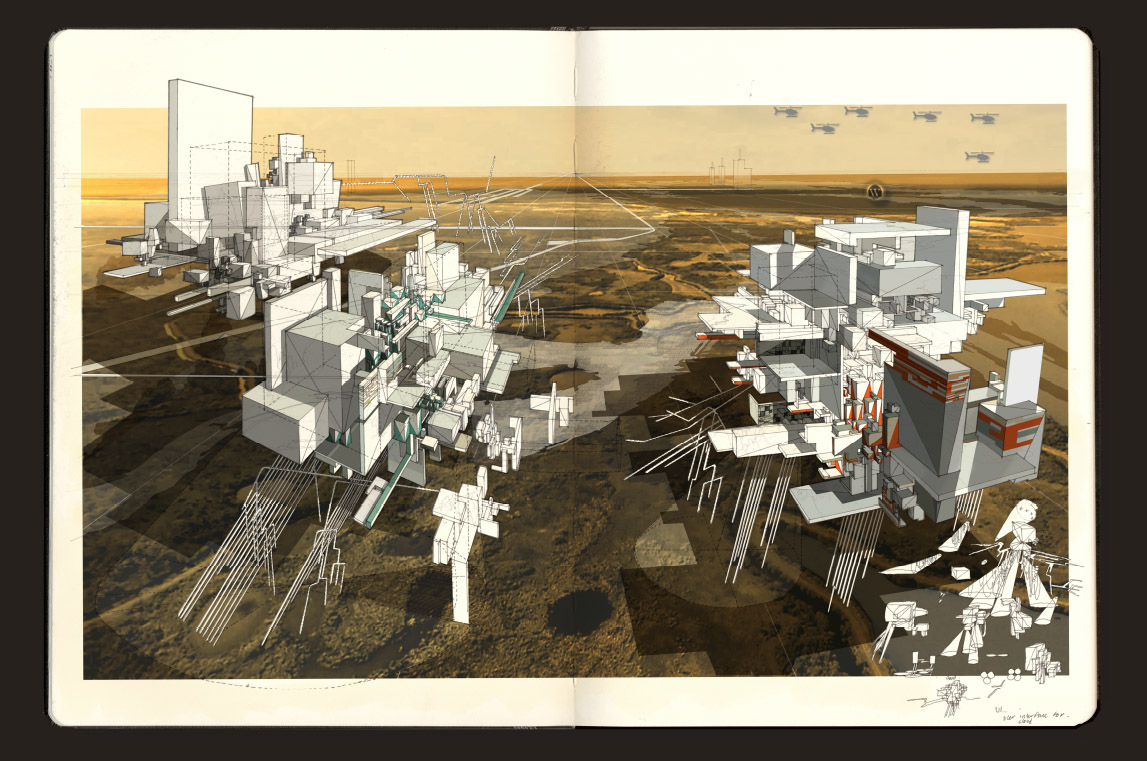

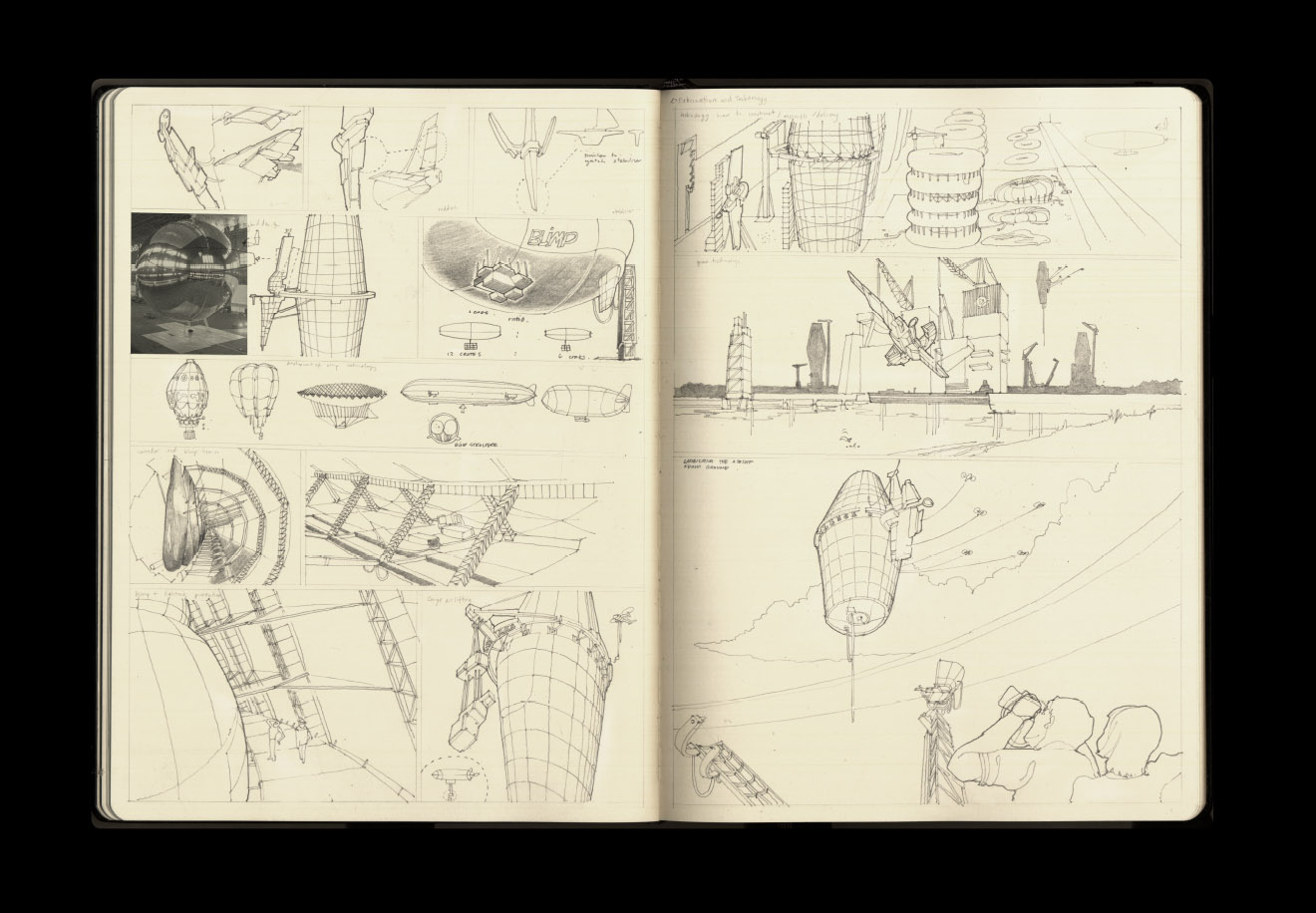

In short, her design proposes a new infrastructure of “rocket-triggered lightning technology,” assisted and supervised by a peripheral network of dirigibles—floating airships that “surround the site and serve as the observatory platform for a proposed lightning visitor centre and the weather research center.”

The former was directly inspired by real-world lightning research equipment found at the University of Florida’s Lightning Research Group.

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida’s Lightning Research Group].

[Image: Triggered lightning technology at the University of Florida’s Lightning Research Group].

Badaruddin’s own rocket triggers would be used both to attract and “to provide direct lightning strikes to the proposed sites,” thus pyrolizing the landscape and purifying both ground water and soil.

[Image: Aerial collage view of the lightning farm, by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

[Image: Aerial collage view of the lightning farm, by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

The result would be a lightning farm, a titanic landscape tuned to the sky, flashing with controlled lightning strikes as the ground conditions are gradually remediated—an unmoving, nearly permanent, artificial electrical storm like something out of Norse mythology, cleansing the earth of toxic chemicals and preparing the site for future reuse.

[Image: Collage of the lightning farm, by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

[Image: Collage of the lightning farm, by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

I should say that my own interest in these kinds of proposals is less in their future workability and more in what it means to see a technology taken out of context, picked apart for its spatial implications, and then re-scaled and transformed into a speculative work of landscape architecture. The value, in other words, is in re-thinking existing technologies by placing them at unexpected scales in unexpected conditions, simultaneously extracting an architectural proposal from that and perhaps catalyzing innovative new ways for the original technology itself to be redeveloped or used.

[Image: Farah Aliza Badaruddin].

[Image: Farah Aliza Badaruddin].

It’s not a question of whether or not something can be immediately realized or built; it’s a question of how open-ended, fictional design proposals can change the way someone thinks about an entire field or class of technologies.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() [Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

But I’ll let Badaruddin’s own extraordinary visual skills tell the story. Most if not all of these images can be seen in a much larger size if you open the images in their own windows; they’re well worth a closer look—

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

—including what amount to a short graphic novel telling the story of her proposed controlled-lightning landscape-decontamination facility.

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

[Images: From a project by Farah Aliza Badaruddin at the Bartlett School of Architecture].

All in all, whether or not architecturally-controlled lightning storms will ever purify the land and water of south Florida, it’s a wonderfully realized and highly imaginative project, and I hope Badaruddin finds more opportunities, post-Bartlett, to showcase and develop her skills.

[Image: Courtesy Oppland County Council. Photo by

[Image: Courtesy Oppland County Council. Photo by  [Image: A shot of the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site by Gleb Raygorodetsky, courtesy of

[Image: A shot of the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site by Gleb Raygorodetsky, courtesy of

[Image: Two shots from the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site by Gleb Raygorodetsky, courtesy of

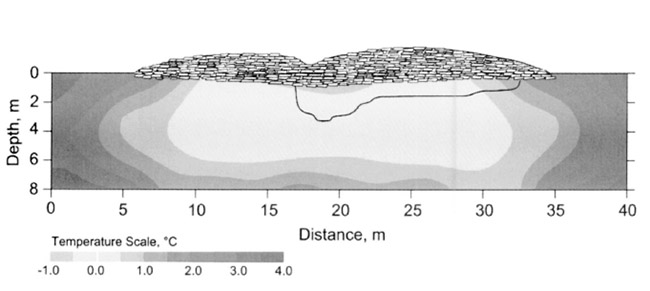

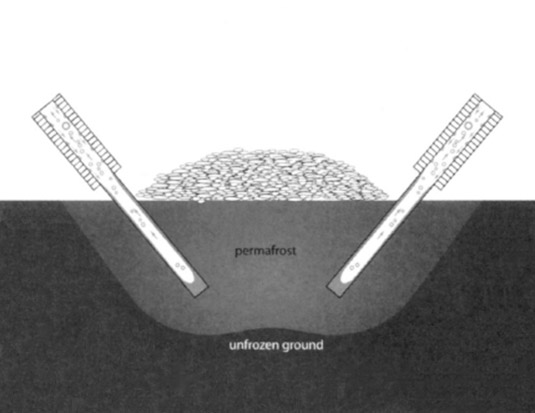

[Image: Two shots from the Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO World Heritage Site by Gleb Raygorodetsky, courtesy of  [Image: Diagram of the thermal effects of an Altai rock tomb or kurgan, from “

[Image: Diagram of the thermal effects of an Altai rock tomb or kurgan, from “ [Image: Diagram of archaeological ground-refrigeration techniques, from “

[Image: Diagram of archaeological ground-refrigeration techniques, from “ [Image: Courtesy Espen Finstad/Oppland County Council. Photos by

[Image: Courtesy Espen Finstad/Oppland County Council. Photos by

[Image: A SWORDS unit firing; photo via

[Image: A SWORDS unit firing; photo via  [Image: Knights at the

[Image: Knights at the

[Image: Ancient Egyptian jewelry made from meteorites; photo courtesy of

[Image: Ancient Egyptian jewelry made from meteorites; photo courtesy of  [Image: Space buddha! Photo by Dr. Elmar Buchner, via

[Image: Space buddha! Photo by Dr. Elmar Buchner, via

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: Another view of “

[Image: Another view of “

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

[Images: “

[Images: “ [Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: “

[Image: “

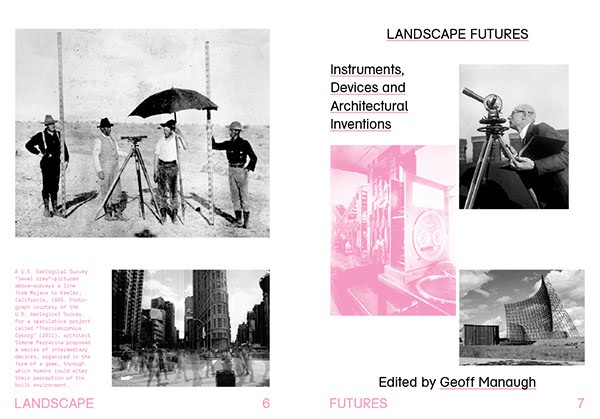

[Image: Internal title page from

[Image: Internal title page from

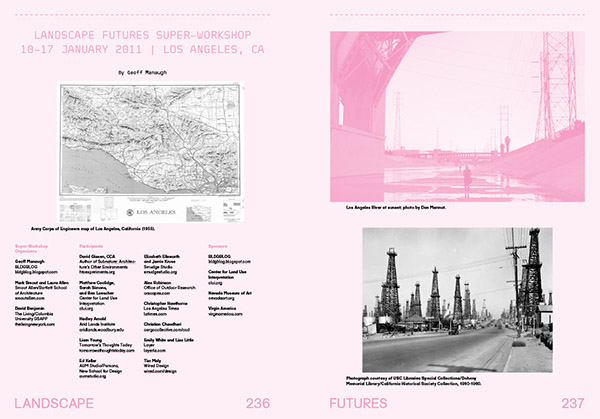

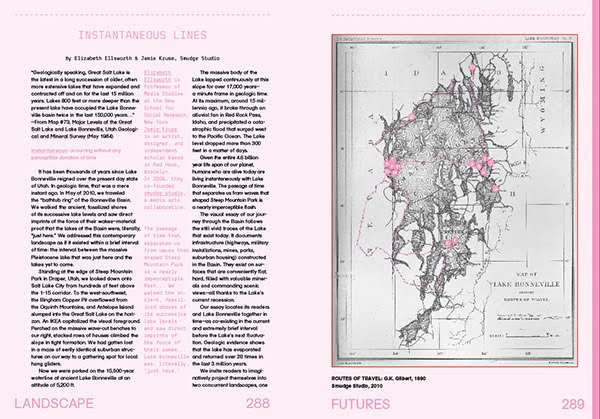

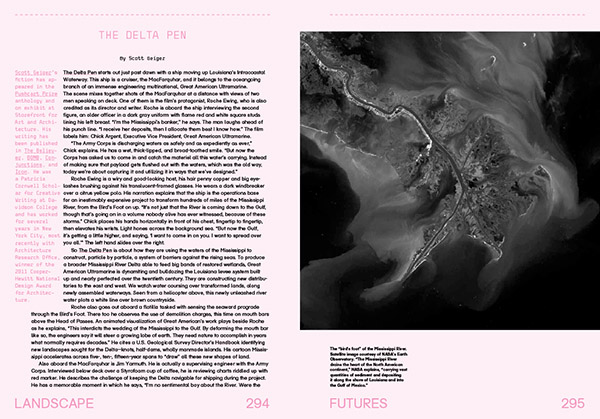

[Images: A few spreads from the “Landscape Futures Sourcebook” featured in

[Images: A few spreads from the “Landscape Futures Sourcebook” featured in

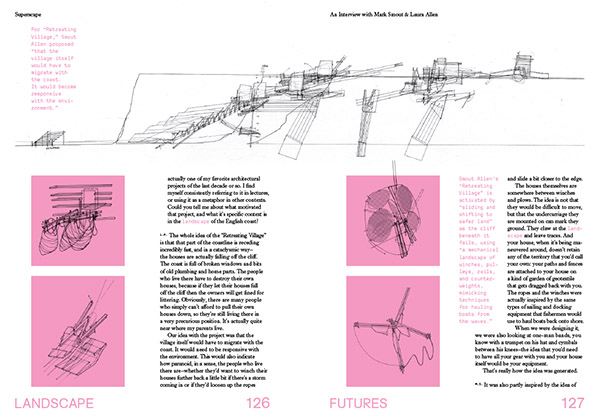

[Images: Interview spreads from

[Images: Interview spreads from

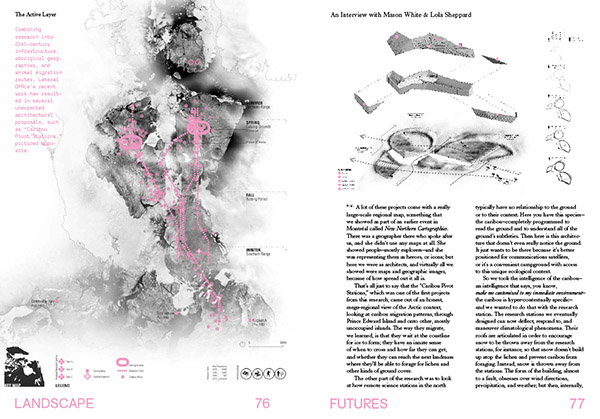

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: Sliced truffles, randomly found via Google].

[Images: Sliced truffles, randomly found via Google].

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the  [Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the  [Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Images: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Images: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the  [Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the  [Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the  [Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

[Image: A telephone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, courtesy of the

Abandoned terrapin turtles purchased 25 years ago at the height of popularity for

Abandoned terrapin turtles purchased 25 years ago at the height of popularity for