Speaking of the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennale, I’m thrilled to be an exhibitor this year in the UK pavilion, as part of a collaborative project undertaken with Mark Smout and Laura Allen of Smout Allen.

[Image: The British Exploratory Land Archive’s “capture blanket” in use on Hampstead Heath, London; photo by Mark Smout].

[Image: The British Exploratory Land Archive’s “capture blanket” in use on Hampstead Heath, London; photo by Mark Smout].

Smout Allen are the authors of Augmented Landscapes, easily one of my favorite installments in the Pamphlet Architecture series, as well as long-time instructors at the Bartlett School of Architecture—in fact, many of their students’ projects have been featured here on the blog over the last half-decade—and working with Mark and Laura on a project such as this has been fantastic.

Specifically, as part of the “Venice Takeaway” project curated by Vicky Richardson and Vanessa Norwood, Smout Allen and I have proposed what we call the British Exploratory Land Archive (or BELA).

The British Exploratory Land Archive is, in essence, a British version of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, albeit one defined as much by the use of unique instruments designed specifically for BELA as by its focus on sites of human land-use in the United Kingdom as by.

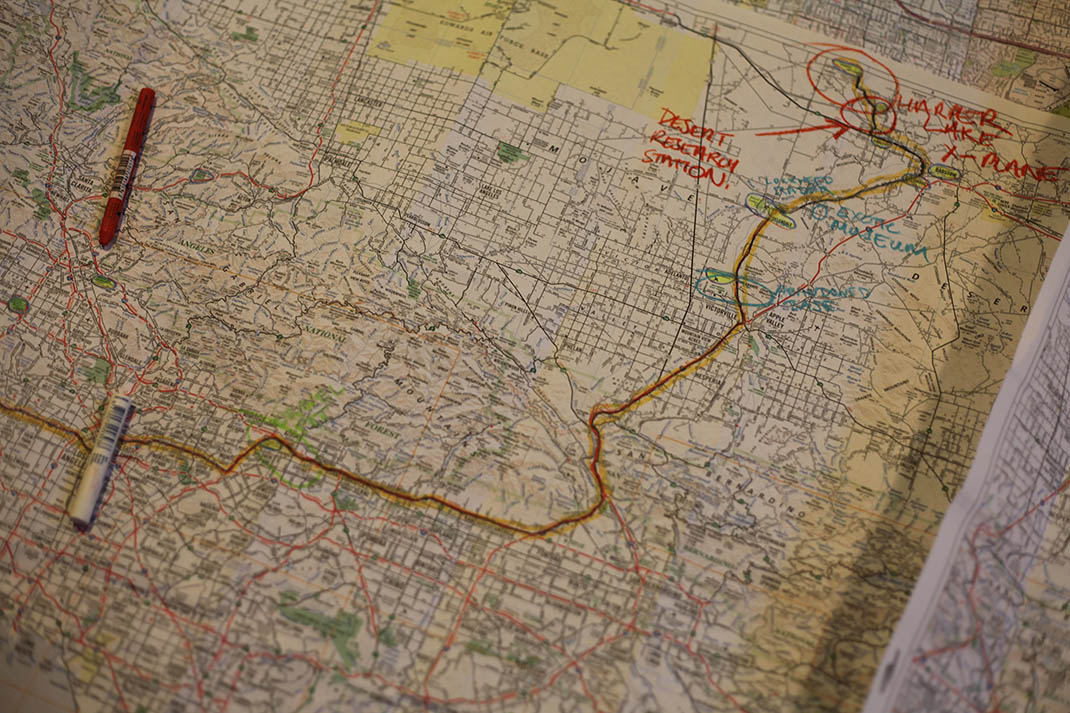

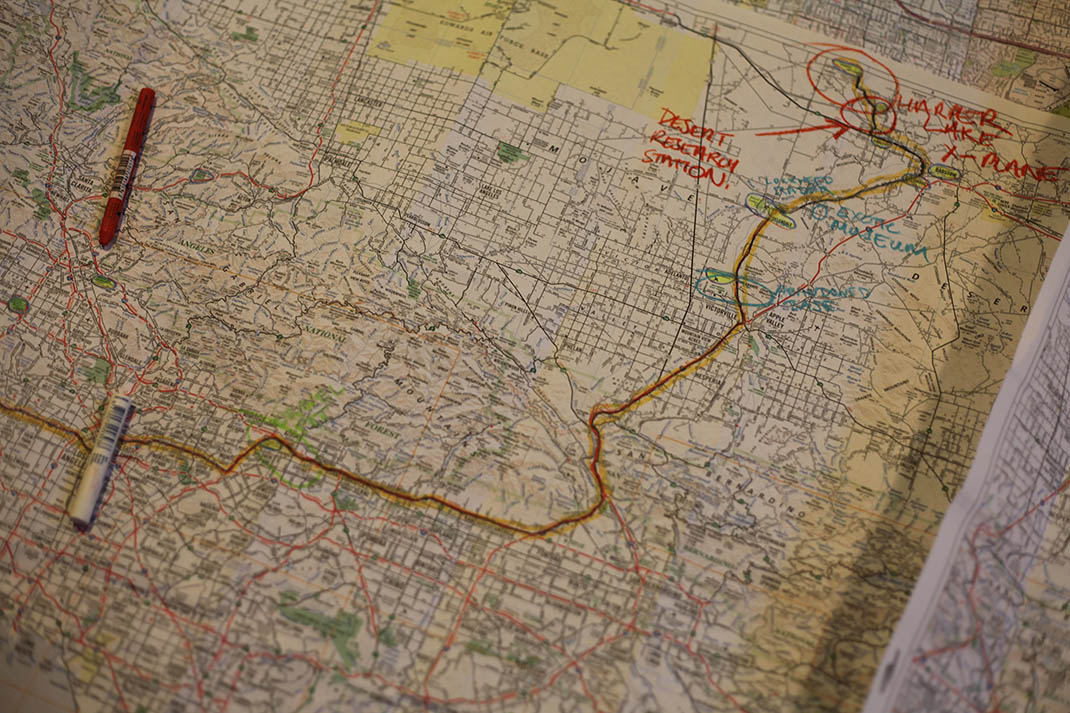

[Images: Going through the archives, maps, and files of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, including one of my favorite headlines of all time: “Emptiness welcomes entrepreneurs”; photos by Mark Smout].

[Images: Going through the archives, maps, and files of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, including one of my favorite headlines of all time: “Emptiness welcomes entrepreneurs”; photos by Mark Smout].

In an essay for the Venice Takeaway book, we describe the inspiration, purpose, and future goals of the—still entirely hypothetical—British Exploratory Land Archive:

BELA is directly inspired by the Los Angeles-based Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI). It aims to unite the efforts of several existing bodies—English Heritage, Subterranea Britannica, the Airfields of Britain Conservation Trust and even the Department for Transport, among dozens of others—in a project of national landscape taxonomy that will combine catalogues created by distinct organisations into one omnivorous, searchable archive of human-altered landscapes in Britain… From military bases to abandoned factories, from bonded warehouses to national parks, by way of private gardens, council estates, scientific laboratories and large-scale pieces of urban infrastructure, BELA’s listings are intended to serve as something of an ultimate guide to both familiar and esoteric sites of human land use throughout the United Kingdom.

In the end, a fully functioning BELA would offer architects, designers, historians, academics, enthusiasts, and members of the general public a comprehensive list of UK sites that have been used, built, unbuilt, altered, augmented and otherwise transformed by human beings, aiming to reveal what we might call the spatial footprint of human civilization in the British Isles.

Thanks to the generosity of the Venice Takeaway organizers, with funding from the British Council, Mark Smout and I had the pleasure of traveling to Los Angeles back in April 2012 specifically to meet with Matthew Coolidge, Sarah Simons, Ben Loescher, and Aurora Tang at the Center for Land Use Interpretation. Even better, we were able to take Matt, Ben, and Aurora out on a daylong road-trip through gravel pits, dry lake beds, Cold War radar-testing facilities, airplane crash sites, logistics airfields, rail yards, abandoned military base housing complexes, and much more orbiting the endlessly interesting universe of Greater Los Angeles.

[Images: Exploring Greater Los Angeles with Matthew Coolidge, Ben Loescher, and Aurora Tang; photos by Mark Smout].

[Images: Exploring Greater Los Angeles with Matthew Coolidge, Ben Loescher, and Aurora Tang; photos by Mark Smout].

That trip was documented in a series of photographs, in a (very) short film, and in the essay mentioned above, all of which will be available for perusal at the UK pavilion for the duration of this year’s Biennale.

I’ll also include here a few diagrams depicting one the instruments Smout Allen and I devised as part of our land-investigation tools—making BELA a kind of second-cousin to Venue—with the real objects, including a portable explorer’s hut, also on display in Venice.

[Images: Assembly diagrams for the BELA “clinometer,” a speculative device “for the measurement of variable slopes on sites such as scrap yards, landfills, slag heaps and other industrial dumping grounds… functioning as an easily readable survey tool and as a unique design object that calls public attention to the process of measuring artificial landscapes”].

[Images: Assembly diagrams for the BELA “clinometer,” a speculative device “for the measurement of variable slopes on sites such as scrap yards, landfills, slag heaps and other industrial dumping grounds… functioning as an easily readable survey tool and as a unique design object that calls public attention to the process of measuring artificial landscapes”].

Taken together, these are what we call, in the essay, “prototypical future survey instruments and experimental site-identification beacons.” They are “both semi-scientific and speculative, portable and permanently anchored.”

From telescopes to Geiger counters, from contact microphones to weather satellites, the devices and scales with which we measure and describe the landscapes around us determine, to a large extent, what we are able to see. BELA will thus work to pioneer the design, fabrication and expeditionary deployment of new landscape survey tools—instruments and devices both functional and speculative that will aid in the sensory cataloguing and interpretive analysis of specific locations.

While the British Exploratory Land Archive is, for now, merely a proposition, I think Mark, Laura, and I are all equally keen to see something come of that proposition, perhaps someday even launching BELA as a real, functioning resource through which the various human-altered landscapes of Britain can be catalogued and studied.

For now, those of you able to visit Venice, Italy, before the end of the 2012 Biennale can see our instruments, photos, drawings, and texts as they currently exist, and, in the process, learn more about the possibilities for a British Exploratory Land Archive.

(Thanks to Sandra Youkhana for her invaluable help with the project, and to Matthew Coolidge, Sarah Simons, Ben Loescher, and Aurora Tang at the Center for Land Use Interpretation for hosting us back in April).

[Image: The howling of Hell, illustrated by Gustave Doré for Dante’s Inferno].

[Image: The howling of Hell, illustrated by Gustave Doré for Dante’s Inferno].

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: Curiosity reveals its Morse code, courtesy of

[Image: Curiosity reveals its Morse code, courtesy of  [Image: Curiosity’s tire treads, courtesy of

[Image: Curiosity’s tire treads, courtesy of

[Image: Bradbury Landing, via the

[Image: Bradbury Landing, via the

[Image: The British Exploratory Land Archive’s “capture blanket” in use on Hampstead Heath, London; photo by Mark Smout].

[Image: The British Exploratory Land Archive’s “capture blanket” in use on Hampstead Heath, London; photo by Mark Smout].

[Images: Going through the archives, maps, and files of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, including one of my favorite headlines of all time: “Emptiness welcomes entrepreneurs”; photos by Mark Smout].

[Images: Going through the archives, maps, and files of the Center for Land Use Interpretation, including one of my favorite headlines of all time: “Emptiness welcomes entrepreneurs”; photos by Mark Smout].

[Images: Exploring Greater Los Angeles with Matthew Coolidge, Ben Loescher, and Aurora Tang; photos by Mark Smout].

[Images: Exploring Greater Los Angeles with Matthew Coolidge, Ben Loescher, and Aurora Tang; photos by Mark Smout].

[Images: Assembly diagrams for the BELA “clinometer,” a speculative device “for the measurement of variable slopes on sites such as scrap yards, landfills, slag heaps and other industrial dumping grounds… functioning as an easily readable survey tool and as a unique design object that calls public attention to the process of measuring artificial landscapes”].

[Images: Assembly diagrams for the BELA “clinometer,” a speculative device “for the measurement of variable slopes on sites such as scrap yards, landfills, slag heaps and other industrial dumping grounds… functioning as an easily readable survey tool and as a unique design object that calls public attention to the process of measuring artificial landscapes”].

Her piece, called Making the walls quake as if they were dilating with the secret knowledge of great powers is, in the words of Michal Libera, the pavilion’s curator, a controlled “amplification of the Polish Pavilion as a listening-system.”

Her piece, called Making the walls quake as if they were dilating with the secret knowledge of great powers is, in the words of Michal Libera, the pavilion’s curator, a controlled “amplification of the Polish Pavilion as a listening-system.” [Image: A sound-study of the 2012 Polish Pavilion by Andrzej Kłosak for Katarzyna Krakowiak].

[Image: A sound-study of the 2012 Polish Pavilion by Andrzej Kłosak for Katarzyna Krakowiak]. [Image: Another sound-study of the 2012 Polish Pavilion by Andrzej Kłosak for Katarzyna Krakowiak].

[Image: Another sound-study of the 2012 Polish Pavilion by Andrzej Kłosak for Katarzyna Krakowiak].

[Images: Photos by Simon Rouby for “

[Images: Photos by Simon Rouby for “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Image: From Nick Foster’s “

[Image: From Nick Foster’s “ [Images: From Nick Foster’s “

[Images: From Nick Foster’s “

[Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: From “

[Image: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Image: Aerial photo of the roundhouses site, courtesy of

[Image: Aerial photo of the roundhouses site, courtesy of

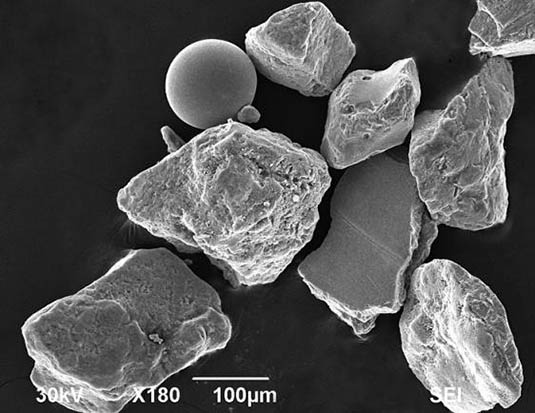

[Images: Sand mines, via Michael Welland’s excellent blog

[Images: Sand mines, via Michael Welland’s excellent blog

[Image: Geologist

[Image: Geologist