A man, unexcited by his own possessions and increasingly confused as to why he collected all these things in the first place, decides to hire someone else to live amidst his books and clothes, DVDs and framed photographs, so that he can learn how another person might more intelligently put it to use.

Perhaps, then, he thinks, he’ll come to appreciate what he owns.

So he submits an ad to Craigslist, interviews dozens of candidates, and soon settles on a one-time professional actor who has since fallen on hard times. They negotiate a one-year contract; catering details are worked out; bank transfers are made. The man’s girlfriend even agrees to take part, as she had once been a fan of the actor’s films.

Then, on a warm summer day, this new man moves into the house.

Overseen by a network of surveillance cameras, he settles into a life amongst the possessions of another. He establishes a breakfast routine, eating from the owner’s tableware, and he familiarizes himself everyday with the material nooks and crannies of another person’s life history, that sediment of souvenirs and home decoration that has developed over time.

The owner, meanwhile, insufficiently awed by the experience of watching someone impersonate himself – wearing his clothes, reading his books, watching his videos, flipping through his college photo albums – finds himself slowly accumulating more possessions. One day he simply gets tired of watching this actor make love to his girlfriend – so he buys a novel to read. But then he finishes that novel.

So he buys another one.

He then ruins a shirt one evening, tearing it on a kitchen implement – so he buys a new shirt. But it comes with 50%-off of a second shirt (so he buys two).

Etc.

Gradually, the memory of those previous possessions – there on film being held by an actor – begins to fade. He no longer misses his girlfriend, and what was once a distracting labyrinth of things that, long ago, lost their attraction becomes something even less meaningful than that.

Soon, he is just watching an expensive folly: a man he doesn’t know, interacting with objects that mean nothing to him.

When it becomes clear that no moment of reconciliation is on its way – no point at which he will learn to love the things he’s accumulated over a lifetime – he simply abandons the project altogether.

He leaves the house and everything in it to the actor, and he waves goodbye to his now ex-girlfriend – who has since fallen in love with his surrogate.

And he walks away.

Month: May 2009

Future Babel

[Image: The Age of Civilization by Jan Soucek].

[Image: The Age of Civilization by Jan Soucek].

Nearly three years ago, in an email I have subsequently misplaced, a reader sent in some scans he had made of a book about Jan Soucek, a Czech artist whose work consists, it seems, almost entirely of elaborate architectural fantasies.

The one image that really stood out for me, and that I’ve just rediscovered here today in the many, many files of images stored on my computer, is called The Age of Civilization: it features the ruined walls and eroding arches of a Brueghelian Tower of Babel, subsequently built over and subsumed beneath future rings of urban growth.

Very little can be found about Soucek online; from what I can gather, though, he was born in 1941 (which means he is not the other Jan Soucek who pops up a lot whilst Googling) and he has participated in “numerous exhibitions in Czech Republic, Germany, Switzerland, Yugoslavia, Rumania, Bulgaria, Austria, France, USA and Belgium.”

A slightly larger version of this very painting was also uploaded to Flickr two years ago – perhaps by the same person who initially sent me the scan (the image description, oddly, mentions BLDGBLOG).

Urban Islands

[Image: For a few heady weeks I actually thought I was going to be teaching at this thing… but no more. Alas. Still, though, how can you resist applying for a two-week architectural design studio in Sydney, Australia, themed around the spatial rehabilitation of a semi-derelict, post-industrial island, complete with “early convict settlement structures” and heavily incised sandstone foundations? More information, including how to apply, available here; larger, though low-res, version of the flyer available here. Have fun!].

[Image: For a few heady weeks I actually thought I was going to be teaching at this thing… but no more. Alas. Still, though, how can you resist applying for a two-week architectural design studio in Sydney, Australia, themed around the spatial rehabilitation of a semi-derelict, post-industrial island, complete with “early convict settlement structures” and heavily incised sandstone foundations? More information, including how to apply, available here; larger, though low-res, version of the flyer available here. Have fun!].

Terrain Deformation Grenades

Something I mentioned the other day in my talk at the Australian National Architecture Conference – and that came up again in Peter Wilson‘s conference summary – was the game Fracture by LucasArts.

Specifically, I referred to that game’s “terrain deformation grenades” (actually, ER23-N Tectonic Grenades).

[Image: A screenshot from Fracture, courtesy of LucasArts].

[Image: A screenshot from Fracture, courtesy of LucasArts].

The game’s own definition of terrain deformation is that it is a “warfare technology” through which “soldiers utilize specialized weaponry to reshape earth to their own strategic advantage.” In an interview with GameZone, David Perkinson, a producer from LucasArts, explains that any player “will be able to use a tectonic grenade to raise the ground and create a hill.”

He will also be able to then lower that same hill by using a subsonic grenade. From there, he could choose to throw another tectonic to rebuild that hill, or add on another subsonic to create a crater in the ground. The possibilities are, quite literally, limitless for the ways in which players can change the terrain.

Other of the game’s terrestrial weapons include a “subterranean torpedo.”

In any case, if you were at the conference and want to know more about either the game or its implications for landscape design, I thought I’d post a quick link back to the original post in which I first wrote about this: Tactical Landscaping and Terrain Deformation.

While we’re on the subject, though, it’d be interesting if terrain deformation weaponry not only was real, but if it could be demilitarized… and purchased at REI.

You load up your backpack with tectonic grenades, head off to hike the Appalachian Trail – and whenever the path gets boring, you just toss a few bombs ahead and create instant slopes and hillsides. An artificial Peak District is generated in northern England by a group of well-armed hikers from Manchester.

In other words, what recreational uses might terrain deformation also have – and need these sorts of speculative tools only be treated as weaponry?

If Capability Brown had had a box of Tectonic Grenades, for instance, England today might look like quite different…

Unbuilt Australia

[Image: The unbuilt Australian World Exposition (1972); read the PDF for more].

[Image: The unbuilt Australian World Exposition (1972); read the PDF for more].

Having just returned from Melbourne, and preparing to go back to Sydney in July, I’ve got Australia on the brain.

Amongst the huge variety of things I’ve come across in the last few days while researching Australian architecture is the AA Prize for Unbuilt Work – particularly the historical series “Unbuilt Australia,” published by Architecture Australia.

[Image: “Perth as it Should Be” (PDF)].

[Image: “Perth as it Should Be” (PDF)].

There are some great stories here, ranging from early plans for “Perth as it Should Be” (check out the PDF) to an under-known, September 1950 sketch by Le Corbusier for the redesign of Adelaide (worth viewing the PDF in full).

Did Corbu’s speculative plans Down Under reveal ideas that he would later go on to build in Chandigarh?

[Image: Corbu’s Adelaide (PDF)].

[Image: Corbu’s Adelaide (PDF)].

One of my favorite unbuilt projects from the series is one that was, in fact, partially implemented: Edwin Codd’s Industrialised Building ’74 project, a prefabricated, modular classroom intended for deployment throughout rural Queensland.

“These schools with flat roofs were slab-on-ground buildings with long axes running east–west on a 1.2-metre module, steel-framed with trusses spanning 10.8 metres at 4.8-metre centres,” Don Watson writes in a brief article (read the PDF). Each structure was “naturally ventilated,” he continues, as well as “strongly coloured: steel framing blue, doors red and distinctive funnel-like downpipes yellow.”

In fact, I’ve been running into more and more plans lately for modular, prefab, easily-deployable instant classrooms – so perhaps a future post is in order, exploring some of those more interesting ideas.

[Image: Edwin Codd’s prefabricated Queensland classrooms (PDF)].

[Image: Edwin Codd’s prefabricated Queensland classrooms (PDF)].

Other projects from the series include a “Venetian ‘City of Hope'” (PDF), a new Australian Parliament House (PDF), a look at something called Hackney Modern (PDF), and the “Dream City of Mackay” (PDF), Karl Langer’s excessively rational plan for a sub-tropical garden city.

[Image: Karl Langer’s “dream city” of Mackay (PDF)].

[Image: Karl Langer’s “dream city” of Mackay (PDF)].

It’s a brilliant series, and it would be extremely interesting to see this reproduced elsewhere – from a regular look at “Unbuilt London” to a series of articles about unrealized Colonial-era plans for U.S. cities. “Unbuilt Philadelphia,” “Unbuilt Savannah,” “Unbuilt Washington D.C.”

Check out the rest of the series at Architecture Australia (scroll down).

The Rentable Basement Maze

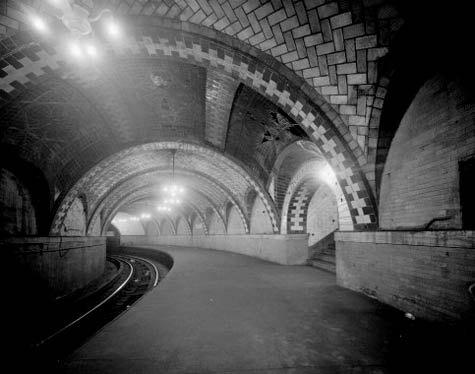

[Image: The subterranean vaults of Manhattan, seen here in City Hall station, which closed in December 1945; photo by David Sagarin (1978), via the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Engineering Record of the Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service].

[Image: The subterranean vaults of Manhattan, seen here in City Hall station, which closed in December 1945; photo by David Sagarin (1978), via the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Engineering Record of the Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service].

A city with an abandoned underground train line, one that cuts beneath some of the nicest townhouses in the city, develops an unexpected new real estate idea: renting out temporary basements in the form of repurposed subway cars.

Access stairs are cut down from each individual house till they connect up with the existing disused train tunnels below; each private residence thus becomes something like a subway station, with direct access, behind a locked door, to the subterranean infrastructure of the city far below.

Then, for a substantial fee – as much as $15,000 a month – you can rent a radically redesigned subway car, complete with closets, shelves, and in-floor storage cubes. The whole thing is parked beneath your house and braked in place; it has electricity and climate control, perhaps even WiFi. You can store summer clothes, golf equipment, tool boxes, children’s toys, and winter ski gear.

When you no longer need it, or can’t pay your bills, you simply take everything out of it and the subway car is returned to the local depot.

A veritable labyrinth of moving rooms soon takes shape beneath the city.

[Image: The great Manhattan underdome, photo by David Sagarin (1978), via the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Engineering Record of the Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service (which includes many other incredible photographs of that subway line)].

[Image: The great Manhattan underdome, photo by David Sagarin (1978), via the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Engineering Record of the Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service (which includes many other incredible photographs of that subway line)].

Within a few years, the market matures.

You can then rent bar cars, home gyms, private restaurants, cheese caves, wine cellars, topless dancing clubs, recording studios, movie theaters, and even an aquarium. You can’t sleep in the middle of the night and so you wander downstairs to look at rare tropical fish, alone with fantastic webworks of coral beneath a slumbering metropolis.

Bespoke planetarium cars are soon developed; you step into your own personal history of the sky every night as the clanking metal of distant private rail switches echoes in the tunnels all around you, basements unlatching and moving on through urban darkness.

Shoe storage. Rare book libraries. Guest bedrooms. Growing operations. Swine flu quarantine facilities.

The catalog of newly mobile subterranean architectural typologies comes to include nearly anything the clients can imagine – or afford. Rumor has it, a particularly wealthy widower on the Upper West Side of Manhattan has whole exhibitions from the American Museum of Natural History parked beneath his house when the Museum closes at night; he goes down in his slippers, and he looks at dinosaur skeletons and gemstones as he thinks about his wife.

But then the economy crashes. The market in rentable basements dries up. The lovingly detailed personalized cars that once trolled around beneath the city are dismantled and sold for scrap.

Within a generation, the very idea that people once had personal access to a migratory maze of temporary rooms far below seems almost impossible to believe.