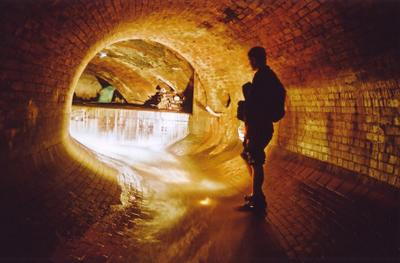

[Image: Embankment, London, ©urban75].

[Image: Embankment, London, ©urban75].

As something of a sequel to BLDGBLOG’s earlier post, Britain of Drains, we re-enter the sub-Britannic topology of interlinked tunnels, drains, sewers, Tubes and bunkers that curve beneath London, Greater London, England and the whole UK, in rhizomic tangles of unmappable, self-intersecting whorls.

[Images: The Bunker Drain, Warrington; and the Motherload Complex, Bristol (River Frome Inlets); brought to you by the steroidally courageous and photographically excellent nutters at International Urban Glow].

[Images: The Bunker Drain, Warrington; and the Motherload Complex, Bristol (River Frome Inlets); brought to you by the steroidally courageous and photographically excellent nutters at International Urban Glow].

Whether worm-eaten by caves, weakened by sink-holes, rattled by the Tube or even sculpted from the inside-out by secret government bunkers – yes, secret government bunkers – the English earth is porous.

“The heart of modern London,” Antony Clayton writes, “contains a vast clandestine underworld of tunnels, telephone exchanges, nuclear bunkers and control centres… [s]ome of which are well documented, but the existence of others can be surmised only from careful scrutiny of government reports and accounts and occassional accidental disclosures reported in the news media.”

[Images: Down Street, London, by the impressively omnipresent Nick Catford, for Subterranea Britannica; I particularly love the multi-directional valve-like side-routes of the fourth photograph].

[Images: Down Street, London, by the impressively omnipresent Nick Catford, for Subterranea Britannica; I particularly love the multi-directional valve-like side-routes of the fourth photograph].

This unofficially real underground world pops up in some very unlikely places: according to Clayton, there is an electricity sub-station beneath Leicester Square which “is entered by a disguised trap door to the left of the Half Price Ticket Booth, a structure that also doubles as a ventilation shaft.”

This links onward to “a new 1 1/4 mile tunnel that connects it with another substation at Duke Street near Grosvenor Square.”

But that’s not the only disguised ventilation shaft: don’t forget the “dummy houses,” for instance, at 23-24 Leinster Gardens, London. Mere façades, they aren’t buildings at all, but vents for the underworld, disguised as faux-Georgian flats.

(This reminds me, of course, of a scene from Foucault’s Pendulum, where the narrator is told that, “People walk by and they don’t know the truth… That the house is a fake. It’s a façade, an enclosure with no room, no interior. It is really a chimney, a ventilation flue that serves to release the vapors of the regional Métro. And once you know this you feel you are standing at the mouth of the underworld…”).

[Image: The Motherload Complex, Bristol – again, by International Urban Glow].

[Image: The Motherload Complex, Bristol – again, by International Urban Glow].

There is also a utility subway – I love this one – accessed “through a door in the base of Boudicca’s statue near Westminster Bridge.” (!) The tunnel itself “runs all the way to Blackfriars and then to the Bank of England.”

Et cetera.

[Images: The Works Drain, Manchester; International Urban Glow].

[Images: The Works Drain, Manchester; International Urban Glow].

My personal favorite by far, however, is British investigative journalist Duncan Campbell’s December 1980 piece for the New Statesman, now something of a cult classic in Urban Exploration circles.

[Image: Motherload Complex, Bristol; International Urban Glow].

[Image: Motherload Complex, Bristol; International Urban Glow].

“Entering, without permission, from an access shaft situated on a traffic island in Bethnal Green Road he descended one hundred feet to meet a tunnel, designated L, stretching into the distance and strung with cables and lights.” He had, in other words, discovered a government bunker complex that stretched all the way to Whitehall.

On and on he went, all day, for hours, riding a folding bicycle through this concrete, looking-glass world of alphabetic cyphers and location codes, the subterranean military abstract: “From Tunnel G, Tunnel M leads to Fleet Street and P travels under Leicester Square to the then Post Office Tower, with Tunnel S crossing beneath the river to Waterloo.”

[Image: Like the final scene from a subterranean remake of Jacob’s Ladder (or a deleted scene from Creep [cheers, Timo]), it’s the Barnton Quarry, ROTOR Drain, Edinburgh; International Urban Glow].

[Image: Like the final scene from a subterranean remake of Jacob’s Ladder (or a deleted scene from Creep [cheers, Timo]), it’s the Barnton Quarry, ROTOR Drain, Edinburgh; International Urban Glow].

Here, giving evidence of Clayton’s “accidental disclosures reported in the news media,” we read that “when the IMAX cinema inside the roundabout outside Waterloo station was being constructed the contractor’s requests to deep-pile the foundations were refused, probably owing to the continued presence of [Tunnel S].”

[Image: Motherload, Bristol; International Urban Glow].

[Image: Motherload, Bristol; International Urban Glow].

But when your real estate is swiss-cheesed and under-torqued by an unreal world of remnant topologies, the lesson, I suppose, is you have to read between the lines.

A simple building permissions refusal might be something else entirely: “It was reported,” Clayton says, “that in the planning stage of the Jubilee Line Extension official resistance had been encountered, when several projected routes through Westminster were rejected without an explanation, although no potential subterranean obstructions were indicated on the planners’ maps. According to one source, ‘…the rumour is that there is a vast bunker down there, which the government has kept secret, which is the grandaddy of them all.'”

[Image: The Corsham Tunnels; see also BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The Corsham Tunnels; see also BLDGBLOG].

Continuing to read between the lines, Clayton describes how, in 1993, after “close scrutiny of the annual Defence Works Services budget the existence of the so-called Pindar Project was revealed, a plan for a nuclear bomb-proof bunker, that had cost £66 million to excavate.”

All of these places have insane names—Pindar, Cobra, Trawlerman, ICARUS, Kingsway, Paddock—and they are hidden in the most unlikely places. Referring to a government bunker hidden in the ground near Reading: “Inside, they tried another door on what looked like a cupboard. This was also unlocked, and swung open to reveal a steep staircase leading into an underground office complex.”

[Images: The freaky stairs and tunnels, encrusted with plaster stalactites, of King William Street].

[Images: The freaky stairs and tunnels, encrusted with plaster stalactites, of King William Street].

Everything leads to everything else; there are doorways everywhere. It’s like a version of London rebuilt to entertain quantum physicists, with a dizzying self-intersection of systems hitting systems as layers of the city collide.

[Image: Belsize Park, from the terrifically useful Underground History of Hywel Williams].

[Image: Belsize Park, from the terrifically useful Underground History of Hywel Williams].

There is always another direction to turn.

[Image: The Shorts Brothers Seaplane Factory and air raid shelter, Kent; photo by Underground Kent].

[Image: The Shorts Brothers Seaplane Factory and air raid shelter, Kent; photo by Underground Kent].

This really could go on and on; there are flood control complexes, buried archives, lost rivers sealed inside concrete viaducts – and all of this within the confines of Greater London.

[Images: London’s Camden catacombs – “built in the 19th Century as stables for horses… [t]heir route can be traced from the distinctive cast-iron grilles set at regular intervals into the road surface; originally the only source of light for the horses below” – as photographed by Nick Catford of Subterranea Brittanica].

[Images: London’s Camden catacombs – “built in the 19th Century as stables for horses… [t]heir route can be traced from the distinctive cast-iron grilles set at regular intervals into the road surface; originally the only source of light for the horses below” – as photographed by Nick Catford of Subterranea Brittanica].

Then there’s Bristol, Manchester, Edinburgh, Kent…

[Image: Main Junction, Bunker Drain, Warrington; International Urban Glow].

[Image: Main Junction, Bunker Drain, Warrington; International Urban Glow].

And for all of that, I haven’t even mentioned the so-called CTRL Project (the Channel Tunnel Rail Link); or Quatermass and the Pit, an old sci-fi film where deep tunnel Tube construction teams unearth a UFO; or the future possibilities such material all but demands.

[Image: Wapping Tunnel Vent, Liverpool, by International Urban Glow; a kind of subterranean Pantheon].

[Image: Wapping Tunnel Vent, Liverpool, by International Urban Glow; a kind of subterranean Pantheon].

Such as: BLDGBLOG: The Game, produced by LucasArts, set in the cross-linked passages of subterranean London, where it’s you, a torch, some kind of weapon, a shitty map and hordes of bird flu infected zombies coughing their way down the dripping passages – looking for you…