[Image: “People wear surgical masks as a precaution against infection inside a subway in Mexico City, Friday, April 24, 2009.” Photo by AP Photo/Marco Ugarte].

[Image: “People wear surgical masks as a precaution against infection inside a subway in Mexico City, Friday, April 24, 2009.” Photo by AP Photo/Marco Ugarte].

1) In his under-appreciated novel Super-Cannes, easily amongst his best, J.G. Ballard explored the psychological, sexual, and even epidemiological implications of landscape design. This is “the secret life of the business park,” Ballard writes.

At one point the book’s narrator is speaking with the corporate director of Eden-Olympia, a planned live/work community in southern France. The director somewhat off-handedly refers to medical research that the narrator’s own wife, a doctor, has been performing: “She’s running a new computer model,” the director says, “tracing the spread of nasal viruses across Eden-Olympia. She has a hunch that if people moved their chairs a further eighteen inches apart they’d stop the infectious vectors in their tracks.”

Perfectly calibrated down to the inch – or perhaps the millimeter – modern space itself becomes a kind of medical regime, its bare white rooms an antiviral treatment that we mistake for interior design.

Just as our city streets are wide enough to accommodate the turning radius of a specific class of passenger vehicle, our office cubicles, kindergarten playrooms, courts of law, and university lecture halls could be measured against the infectious vectors of specific pathogens.

In the geometry of objects around us are the outer infectious edges of diseases we no longer suffer from; we have literally designed them out of modern space, denying their ability to spread.

2) You go to the Salone del Mobile next year in Milan and discover that the CDC has unexpectedly released a new line of furniture. Each piece varies just slightly from the rest, in that their measurements have been dictated not by human comfort, international rates of shipment, or even by industrial timber specifications, but by the distances medically necessary to maintain between yourself and others in order to avoid respiratory infections.

The common flu is now a dining table measured exactly against the reach of sneezes; SARS is a cubicle lined with an industrial felt that absorbs all coughs; pneumonia is a bar stool, hand-crafted from white pine, with a circumference of rails to prevent people getting too close.

3) The recent outbreak of swine flu in and around Mexico City and the U.S. border region, is “suspected of killing at least 60 people,” the BBC reports. In fact, the outbreak “has the potential to become a pandemic,” according to Margaret Chan, current director of the World Health Organization.

Chan has “confirmed the virus was an animal strain – a mixture of swine, human and avian flu viruses,” which the BBC points out “is a classic ‘re-assortment’ – a combination feared most by those watching for the flu pandemic.”

[Image: Like the beginning of a zombie horror film, we read – via Twitter – “SWINE FLU SPREADING, CANNOT BE CONTAINED” (via @alexismadrigal)].

[Image: Like the beginning of a zombie horror film, we read – via Twitter – “SWINE FLU SPREADING, CANNOT BE CONTAINED” (via @alexismadrigal)].

It’s interesting to note, however, that swine flu, unsurprisingly, comes from “close contact with pigs” – that is, spatial proximity between humans and their livestock.

Swine flu, we could say, is a spatial problem – an epiphenomenon of landscape.

I’m reminded here of a point made recently by geographer Javier Arbona. Referring to the increasingly popular and somewhat utopian idea that, in the sustainable cities of tomorrow, agriculture will have returned to its rightful place in the city center, Arbona asks: “Did everyone think that so much lushness and farming envisioned in the city aren’t going to open up new Pandora’s boxes of infectious diseases and sanitation problems as we come into contact with more manure, more bacteria, and more wild animals that we urbanites are not at all ‘naturalized’ to?”

It’s an important question. After all, it’s incredibly easy, reading about sustainable cities, urban agriculture, and even the locavore movement, to conclude that chickens, pigs, cows, etc., have all been removed from the urban fabric as part of a profiteering move by Tyson and Perdue.

But there were very real epidemiological reasons for taking agriculture out of the city; finding a new place for urban farms will thus not only require very intense new spatial codes, it will demand constant vigilance in researching and developing inoculations. Few people want to see burning piles of livestock in Times Square or Griffith Park, let alone piles of human corpses infected with H5N1.

Indeed, one of the most prevalent, if mundane, reasons why avian flu has become a “global threat” to humankind, as Mike Davis refers to it in his book Monster At Our Door, is space: it sounds like a joke, but people are living too close to their chickens (or their pigeons, as the case may be).

Avian flu, foot-and-mouth disease, swine flu: if these are spatially activated, so to speak, and spread through certain unrecommended proximities between humans and animals, then urban design’s medical undergirding is again revealed.

The space around you is no mere architectural stylization; it is a strategy of containment. The modern city would thus not only be a place to live – it would also be a functioning medical instrument.

[Image: From “Change of Heart: Rethinking the Prescriptive Medical Environment” by Marina Nicollier].

[Image: From “Change of Heart: Rethinking the Prescriptive Medical Environment” by Marina Nicollier].

4) This brings to mind Marina Nicollier’s final thesis project at Rice University, wherein she explored the medical effects of architectural design.

Part of her project dealt with the history of sanitarium architecture and, from there, the health implications of modern architecture. She wrote:

Popular ideas about what constitutes a healthy environment gave rise to many of the components that became the formal trademarks of modernism – the flat roof was devised as a means to provide additional sunning surfaces for tubercular patients; while the deep verandas, wide private balconies, and covered corridors served as organizational tools to isolate contagious patients from the general staff.

In other words, at its origins, modern architecture was a kind of medical prescription – not a pill you swallowed but an environment you surrounded yourself with.

Nicollier continues:

Visits to these establishments were prescribed, as were the conditions and durations of the exposures themselves. Today, of course, there is ongoing research to determine how and to what extent environmental factors such as temperature, natural and artificial light, and sound affect our health, and despite there having been some interesting conclusions, it is still an area of research that requires more investigation and exploratory trials.

This idea, of controlled exposure to specific architectural forms, makes the equation between built space and medical treatment explicit.

How, then, might we expand and re-apply this research to whole cities in an era of swine flu and SARS?

[Image: Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin for Paris].

[Image: Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin for Paris].

5) The medical aspects of utopia seem under-explored in contemporary urban literature. Here, utopia could be retheorized as the city where no one gets sick. Through microbe-resistant building materials and a precisely measured anti-contagious spatiality, perhaps, your metropolis might even cure you.

Utopia becomes a hospital ward the size and shape of a city.

Perhaps BLDGBLOG should sponsor a new urban design competition in which only medical doctors can participate. Design your vision of the healthy city, these doctors will be told; what urban forms will result?

Briefly, I’m reminded of BLDGBLOG’s 2006 interview with Mike Davis. Referring, again, to his book Monster At Our Door and its exploration of biosecurity, I asked Davis: “What would a biosecure world actually look like, on the level of architecture and urban design? (…) Do you see any evidence that the medical profession is being architecturally empowered, so to speak, influencing the design of ‘disease-free’ public spaces?”

Davis replied that this was “exactly how Victorian social control over the slums was defined as a kind of hygienic project – or in the same way that urban segregation was justified in colonial cities as a problem of sanitation. Everywhere these discourses reinforce one another.”

Further:

Davis: Just as the Victorian middle classes could not escape the diseases of the slums, neither will the rich, bunkered down in their country clubs or inside gated communities. The whole obsession now is that avian flu will be brought into the country by –

BLDGBLOG: A Mexican!

Davis: Exactly: it’ll be smuggled over the border – which is absurd. This ongoing obsession with illegal immigration has become a one-stop phantasmagoria for… everything. Of course, it goes back to primal, ancient fears: the Irish brought typhoid, the Chinese brought plague. It’s old hat.

The fact that this week’s swine flu outbreak originated in Mexico seems doubly interesting in this context.

You can check out the interview for the rest of Davis’s answer – but I still think the question of urban biosecurity deserves more architectural attention.

If the Centers for Disease Control could design a city, what would it look like? Could there be a medical equivalent of Baron Haussman or Robert Moses?

What is medical urban design?

[Image: Robert Moses stands above a model of the city he would create; via Wikipedia].

[Image: Robert Moses stands above a model of the city he would create; via Wikipedia].

6) Producing a disease-free city, of course, requires the proper design tools.

Via Twitter (@qimet888), I was pointed toward a demonstration program: Dynamical Network Design for Controlling Virus Spread.

The clunkily-named program “shows the dynamics of the spread of the SARS virus in Hong Kong’s 18 districts when the optimal resources allocation is used.”

In the simulation, the color green represents an infection-free district, that is, one in which the number of infected people is smaller than one. For infected districts, shades of red are used to indicate the level of infection. Darker red means that there are more infected people in the region and lighter red means that fewer people are infected. The viewer can see that the virus is stopped very quickly using the optimal design: the regions quickly turn green regardless of the initial conditions.

The implication seems clear: toggle your parameters – move people, buildings, walls, hospital wards, sewers, etc., around until you find the right combination – and your city itself might help to eradicate disease.

It would “stop the infectious vectors in their tracks,” as Ballard wrote.

[Image: Of SARS and the city: from Wolfram’s Dynamical Network Design for Controlling Virus Spread].

[Image: Of SARS and the city: from Wolfram’s Dynamical Network Design for Controlling Virus Spread].

7) Why not turn this into a game?

Design the ultimate disease-free city: SimCity: Dark Winter, Urban Outbreak, or even a biomedical version of Settlers of Catan. Your goal is to redesign a city in real-time in order to extinguish a burgeoning plague epidemic. Perhaps SOM could sponsor it – and own rights over the winning results – in an attempt to corner the market in infection-free city planning.

You could even reverse the game’s moral order and require players to create the ideal city for disease transmission: whoever kills off their entire game’s population in the shortest period of time wins. The all-time winner infects the world in less than a second.

8) All of this occurs as I’ve been reading Steven Johnson’s book The Ghost Map. The book consistently raises the issue of public health as an urban design concern – and, at the risk of repeating myself here, it would seem like epidemiology should be a vital part of all city planning courses. Spatial epidemiology, in fact, seems so interesting, and so important, that I’m almost tempted to go back to school for it.

A great final thesis would be a series of test landscapes – epidemiological prototypes – in which hypothetical diseases run their course against a landscape of airlocks and plastic sheeting, chairs moved 18″ further apart, walls erected where there once were screens, and sewers buried another three feet deeper underground. Pushed too far, one of the resulting landscapes becomes completely abiological, incapable of supporting life, sterilizing everything through the design of space alone.

In any case, Johnson’s book is an impressively multi-scalar look at how apparently simple urban design decisions can produce very tragic effects in indirect arenas, elsewhere. Add to this demographic information about who lived where in London at the time, the economics of things like 19th-century water delivery, and the changing nature of medical treatment, and you get a fascinating look at how certain cities either cultivate or effectively stop the spread of diseases.

In the face of very real medical concerns, I might suggest that designing our cities according to historical expectations – let alone according to the spatial needs of the automotive industry – has never seemed quite so arbitrary.

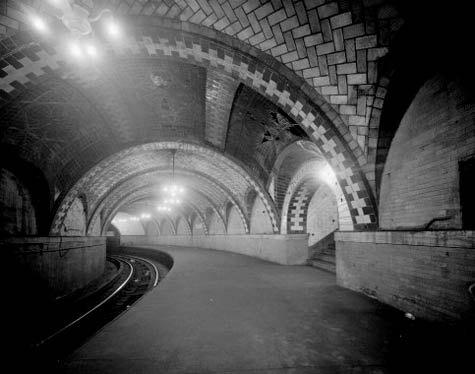

[Image: The sewers of Paris as photographed by Nadar; taken from an article by Matthew Gandy].

[Image: The sewers of Paris as photographed by Nadar; taken from an article by Matthew Gandy].

9) With apologies for a brief personal anecdote, I was in Paris for a week in the fall of 1997; having just read Foucault’s Pendulum for the second and third times, respectively, earlier that summer – somewhat inexplicably, I’ve read that book nine times now – I decided to take a tour of the Paris sewer system.

My “tour group,” such as it was, consisted solely of myself and another American backpacker, who had just finished reading The Coming Plague by Laurie Garrett a few nights before. Doing so apparently made him obsessed with cancer; it was the only thing he talked about.

As the two of us walked through the unbelievable stench of Parisian wastewater, watching used condoms float by and rats crawl away in the darkness ahead, and while we listened to the slightly bemused narration of our female tour guide, the backpacker began telling me about the possible viral nature of cancer, the incurability of certain forms of the disease, and the inevitability that most of us would, in the end, develop it.

Strolling around through fecally-contaminated vaults beneath the city, discussing the history of urban sanitation amidst unhinged speculations about the possibly infectious nature of certain types of cancer, I could joke that the tour’s end didn’t come fast enough, but I was fascinated.

Between experiential urban infrastructure, Victor Hugo’s subterranean chase scene in Les Misérables, and an overwhelming desire to spray myself with deodorant, it nonetheless could have been the ideal setting for a walking salon, so to speak, a conversational meeting of the minds about disease and the city.

Call it The Dante Project™: get doctors from around the world together in Paris every year for a series of long strolls through the well-sewered underworld. Swine flu, cholera, H5N1, cancer, AIDS, ebola: never again will they be as viscerally reminded of what they’ve devoted their lives to cure.

10) In the end, then, what spatial form might a medical utopia take, and how could it be architecturally realized?

In 50 years will you be walking around the edges of the city with your grandkids when one of them asks: Why are these buildings out here, so far away from the rest?

And you’ll say: They’re here because of swine flu. We redesigned the city and our diseases went away.

[Image: An installation of work by photographer JR on the walls of a Rio favela].

[Image: An installation of work by photographer JR on the walls of a Rio favela]. [Image: Work by JR in Rio].

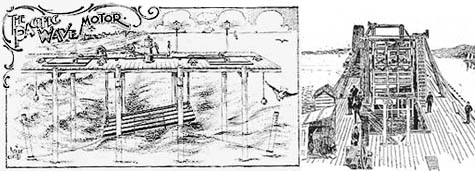

[Image: Work by JR in Rio]. [Image: The Pacific Wave Motor, via the San Francisco

[Image: The Pacific Wave Motor, via the San Francisco  [Images: The Santa Cruz Wave Motor, originally from Scientific American; via

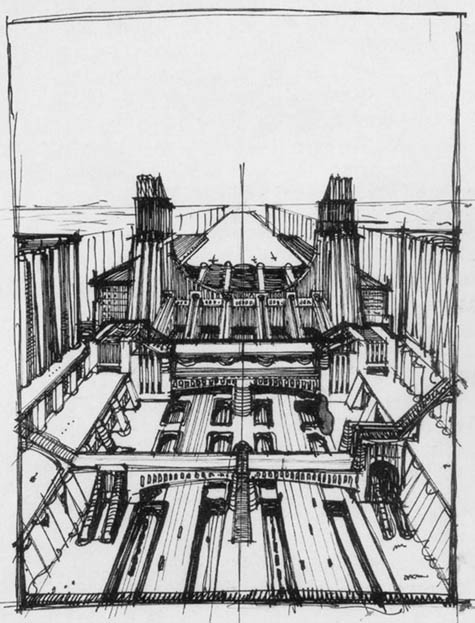

[Images: The Santa Cruz Wave Motor, originally from Scientific American; via  [Image: Constant’s

[Image: Constant’s  [Images: A postcard featuring the Santa Cruz Wave Motor; via

[Images: A postcard featuring the Santa Cruz Wave Motor; via  [Images: Via the

[Images: Via the  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Sant’Elia’s Città Nuova; alternatively, imagine a future Hydroelectric Monastery designed by

[Image: Sant’Elia’s Città Nuova; alternatively, imagine a future Hydroelectric Monastery designed by  [Image: The Age of Civilization by Jan Soucek].

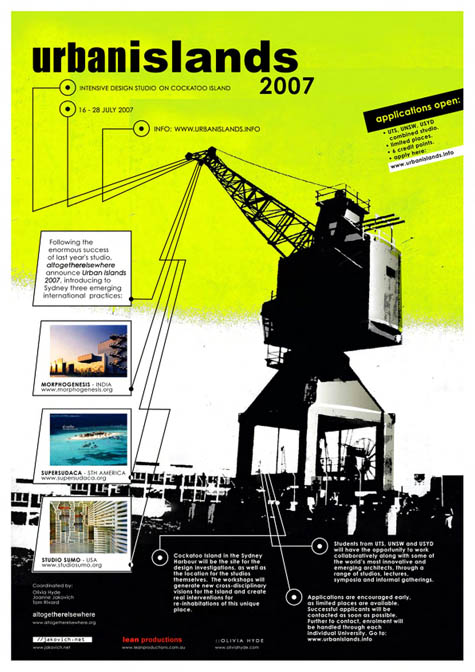

[Image: The Age of Civilization by Jan Soucek]. [Image: For a few heady weeks I actually thought I was going to be teaching at this thing… but no more. Alas. Still, though, how can you resist applying for a two-week architectural design studio in Sydney, Australia, themed around the spatial rehabilitation of a semi-derelict, post-industrial island, complete with “early convict settlement structures” and heavily incised sandstone foundations? More information, including how to apply, available

[Image: For a few heady weeks I actually thought I was going to be teaching at this thing… but no more. Alas. Still, though, how can you resist applying for a two-week architectural design studio in Sydney, Australia, themed around the spatial rehabilitation of a semi-derelict, post-industrial island, complete with “early convict settlement structures” and heavily incised sandstone foundations? More information, including how to apply, available  [Image: A screenshot from

[Image: A screenshot from  [Image: The unbuilt Australian World Exposition (1972); read the

[Image: The unbuilt Australian World Exposition (1972); read the  [Image: “Perth as it Should Be” (

[Image: “Perth as it Should Be” ( [Image: Corbu’s Adelaide (

[Image: Corbu’s Adelaide ( [Image: Edwin Codd’s prefabricated Queensland classrooms (

[Image: Edwin Codd’s prefabricated Queensland classrooms ( [Image: Karl Langer’s “dream city” of Mackay (

[Image: Karl Langer’s “dream city” of Mackay ( [Image: The subterranean vaults of Manhattan, seen here in

[Image: The subterranean vaults of Manhattan, seen here in  [Image: The great Manhattan underdome, photo by

[Image: The great Manhattan underdome, photo by  My subject will be architectural media, broadly speaking, in a dual session co-hosted with Aaron Betsky:

My subject will be architectural media, broadly speaking, in a dual session co-hosted with Aaron Betsky: [Image: “People wear surgical masks as a precaution against infection inside a subway in Mexico City, Friday, April 24, 2009.” Photo by

[Image: “People wear surgical masks as a precaution against infection inside a subway in Mexico City, Friday, April 24, 2009.” Photo by  [Image: Like the beginning of a zombie horror film, we read – via Twitter – “SWINE FLU SPREADING, CANNOT BE CONTAINED” (via @

[Image: Like the beginning of a zombie horror film, we read – via Twitter – “SWINE FLU SPREADING, CANNOT BE CONTAINED” (via @ [Image: From “

[Image: From “ [Image: Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin for Paris].

[Image: Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin for Paris]. [Image: Robert Moses stands above a model of the city he would create; via

[Image: Robert Moses stands above a model of the city he would create; via  [Image: Of SARS and the city: from Wolfram’s

[Image: Of SARS and the city: from Wolfram’s  [Image: The sewers of Paris as photographed by

[Image: The sewers of Paris as photographed by  [Image: “I’m Spanish Moss!” Photo by

[Image: “I’m Spanish Moss!” Photo by