[Image: Hyde Park, London. Image courtesy of The Royal Parks].

[Image: Hyde Park, London. Image courtesy of The Royal Parks].

Note: This is a guest post by Nicola Twilley.

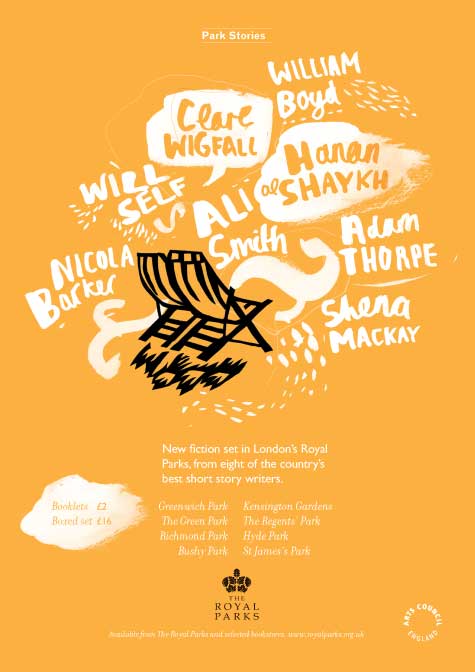

The Royal Parks of London already boast a long list of worthy, if specialized, publications, from the Kensington Gardens Shared Use Assessments to an executive summary of the Cycle Review at The Regent’s Park. But Thursday, May 7, 2009, will open a new chapter in The Royal Parks’ publishing career, as the organization unveils Park Stories, a set of eight specially-commissioned short stories, each story set in one of London’s public parks.

[Image: A poster for the Park Stories project, produced by The Royal Parks under the direction of Rowan Routh].

[Image: A poster for the Park Stories project, produced by The Royal Parks under the direction of Rowan Routh].

According to the series’ editor, Rowan Routh, the seeds of her idea were sown during a recent collaboration with London’s Natural History Museum. The Curator for Contemporary Arts at the NHM, Bergit Arends, worked with Routh to commission literary responses—some poems and a short story—to the life and scientific theories of Charles Darwin, for their current exhibition. The creative challenges of incorporating a substantial reading experience into the limited space of a crowded museum, as well as the quality of the writing that emerged from the commission, left Routh “thinking about fiction in terms of other places to experience it,” she explained in a telephone interview with BLDGBLOG.

Routh is also a champion of the short story form—which she feels has been neglected in the UK—and a Londoner who enjoys the city’s parks, so she was thrilled to find a way to bring all three enthusiasms together: “It just suddenly occurred to me: Hang on a minute, a park is a wonderful place to read! It’s a perfect marriage, really, of a location and an activity. Once the idea formed, it became more and more of a no-brainer, to the point where I was wondering why people haven’t done this before. People spend their lunch breaks in the park. It’s an amount of time in which the golden nugget of the short story can be consumed. And even more to the point, London’s Royal Parks have an incredibly rich literary history anyway, so it’s something that is sort of already there.”

[Image: St. James’s Park, London. Image courtesy of The Royal Parks].

[Image: St. James’s Park, London. Image courtesy of The Royal Parks].

The project is exciting on a number of different levels. For starters, Routh has assembled a stellar list of writers: she has a background as a literary agent, and for her, “It was very important that this was about the short story as well as about parks. It was important that it was about good writing. Commissioning stories for The Royal Parks, when they already have a history of Virginia Woolf, Charles Dickens, and Henry James writing about them, it seemed right to keep to the gold standard.”

She started out by asking writers who had a connection to a particular part of London: for example, Nicola Barker, whose most recent novel is the Booker-prize short-listed Darkmans and who lives in Greenwich, has contributed By Force of Will Alone, set in Greenwich Park. The selection process evolved as word spread—and the final list now looks like this: William Boyd (The Dreams of Bethany Mellmoth, Green Park), Will Self (A Report to the Minister, Bushy Park), Ali Smith (The Definite Article, Regent’s Park), Adam Thorpe (Direct Hit, Hyde Park), Shena Mackay (The Return of the Deer, Richmond Park), Hana al-Shaykh (A Beauty Parlour for Swans, Kensington Gardens), and Clare Wigfall (Along Birdcage Walk, St James’s Park).

[Image: Kensington Gardens, London. Image courtesy of The Royal Parks].

[Image: Kensington Gardens, London. Image courtesy of The Royal Parks].

Routh hopes that the Royal Parks commission will become an annual event, and the potential for this series to evolve in future years is energizing. Her hope is that the project’s core remains “eight very high quality short stories set in the parks,” but she speculates that it could expand to include responses to the parks in different genres or even stories by the general public (through a park-based storybooth or wiki page). Crime writers could make use of fog, weed-choked ponds, and overgrown outhouses to do away with early morning joggers, and sci-fi novelists could set stories in the drowned parks of London’s watery future; it’s even possible to imagine an erotic fiction series (complete with a foreword by George Michael). Meanwhile, the authors of historical romances could bring to life Hyde Park’s Rotten Row, once the gathering place for fashionable London, while horror writers would be drawn instead to the park’s off-limits pet cemetery (which George Orwell apparently considered “perhaps the most horrible spectacle in Britain.”)

Equally pleasing is the formal connection between parks and short stories: both offer a limited space of encounter, but a heightened, or concentrated, experience for all that. In a park, various elements—trees, follies, flowerbeds, and water features—are carefully, even narratively, arranged to mimic, distill, and often improve on the unplanned, “natural” landscape they replace; similarly, Routh contends that short stories “don’t give any less of an emotional or stylistic punch than a novel, and it’s actually heightened and changed by being so carefully contained and arranged in a smaller space.” This idea that a particular landscape can be married to its equivalent literary form is inspiring: perhaps suburbia is best expressed through the sprawling novel; wilderness requires poetry; and a city like Tokyo all but demands a text-message thriller.

[Image: Another view of St. James’s Park, London. Image courtesy of The Royal Parks].

[Image: Another view of St. James’s Park, London. Image courtesy of The Royal Parks].

Finally, the real joy in this project lies in the idea that the owners of a particular landscape or building might commission original literature to celebrate and promote it. If literary commissions become a form of property investment, for instance, could we perhaps see bespoke short stories replacing new kitchen cabinets as the surest way to add value to your home? Or will Los Angeles’ real estate developers forego glossy brochures in favor of paying T.C. Boyle to set his next novel in the city’s struggling loft district, while the local Convention & Visitors Bureau cancels its regular press junkets and instead develops a package of incentives for writers prepared to use L.A. as the backdrop for their work?

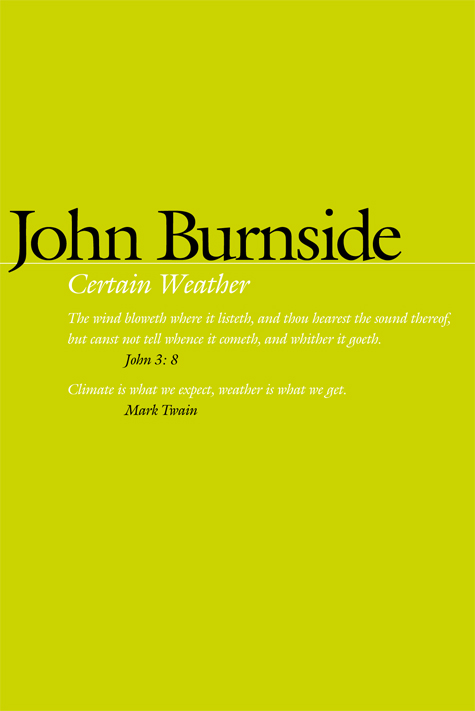

Some critics have caviled, finding “precious few examples of good literature being written to order,” but I rather agree with former Poet Laureate Andrew Motion, who felt that his poems, “like all commissioned pieces, work best when they coincide with an existing personal interest.” Within this fruitful framework of shared interests, for example, we already have Lloyd’s of London commissioning poems from John Burnside on the subject of climate change (which is the insurance industry’s greatest threat to profitability as well as a passionate concern for the Scots nature poet). But what about Sigalert.com drumming up customers for its personalized traffic reports through hourly freeway-themed haiku delivered to your smartphone, or NASA campaigning for a manned Mars program by commissioning dozens of screenplays on the subject?

[Image: From John Burnside’s collection Trees in the City; check out the PDF].

[Image: From John Burnside’s collection Trees in the City; check out the PDF].

Of course, this type of content-specific literary commission is indistinguishable from product placement—and here I feel compelled to mention the example set by Fay Weldon’s 2001 novel The Bulgari Connection. Weldon’s book was commissioned by the eponymous jewelers, who paid an “undisclosed, but ‘not huge’ amount of money,” according to Weldon’s agent, Giles Gordon, for a dozen mentions of their company in the book. Bulgari were, in fact, rewarded with at least three times as many—not to mention the title. With pitch-perfect po-mo sensibility, critics sniped in the New York Times, “It is like the billboarding of the novel. [Note: How about novelizing the billboard?] I feel as if it erodes reader confidence in the authenticity of the narrative. Does this character really drive a Ford or did Ford pay for this?”

In any case, if The Royal Parks are creative and brave enough to commission a set of short stories, I would hope that perhaps the fictionally fertile landscapes built and managed by KB Home (who, in fact, have already partnered with Disney), the Parking Company of America, or the incorporated gated communities of Southern California cannot be far behind?

The Park Stories series will be available from May in eight individual booklets (priced at £2 each) and as a boxed-set (priced at £16) from selected bookstores and The Royal Parks website: (www.royalparks.org.uk). The authors will be conducting readings in the parks this summer.

[Earlier posts by Nicola Twilley include Park’s Parks, Dark Sky Park and Zones of Exclusion; we’ve started joking that she’s our Parks Correspondent).

[Image: “Daechi Dong,” a photo by

[Image: “Daechi Dong,” a photo by

[Images: “Howon Dong” and “Sinbong Dong 2,” photos by

[Images: “Howon Dong” and “Sinbong Dong 2,” photos by

[Images: “Samsung Dong” and “Uman Dong,” photos by

[Images: “Samsung Dong” and “Uman Dong,” photos by  [Image: “Sindorim Dong” by

[Image: “Sindorim Dong” by

[Images: “Jangan Dong” and “Sinbong Dong,” photos by

[Images: “Jangan Dong” and “Sinbong Dong,” photos by