This is the second part of a two-part interview with Mike Davis, author, sociologist, and urban theorist, recorded upon the publication of his book, Planet of Slums. If you missed part one, here it is.

In this installment, Davis discusses the rise of Pentecostalism in global mega-slums; the threat of avian flu; the disease vectors of urban poverty; criminal and terrorist mini-states; the future of sovereignty; environmental footprints; William Gibson; the allure of Hollywood; and Viggo Mortensen‘s publishing imprint, Perceval Press.

•BLDGBLOG:

In an earlier, essay-length version of Planet of Slums, you write at some length about the rise of Pentecostalism as a social and organizational force in the slums – but that research is missing from the actual book, Planet of Slums. Are you distancing yourself from that research, or perhaps less interested now in its implications?

Davis: Actually, several hundred pages on Pentecostalism are now being decanted in the second volume, written with Forrest Hylton, where they properly belong. But the historical significance of Pentecostalism – evangelical Christianity – is that it’s the first modern religious movement, I believe – or religious sect – which emerged out of the urban poor. Although there are many gentrified Pentecostal churches in the United States today, and even in places like Brazil, the real crucible of Pentecostalism – the spiritual experience which propels it – the whole logic of Pentecostalism – remains within the urban poor.

Of course, Pentecostalism, in most places, is also, overwhelmingly, a religion of women – and in Latin America, at least, it has an actual material benefit. Women who join the church, and who can get their husbands to join with them, often see significant increases in their standard of living: the men are less likely to drink, or whore, or gamble all their money away.

For someone like myself, writing from the left, it’s essential to come to grips with Pentecostalism. This is the largest self-organized movement of poor urban people in the world – at least among movements that emerged in the twentieth century. It has shown an ability to take root, dynamically, not only in Latin America but in southern and western Africa, and – to a much smaller extent – in east Asia. I think many people on the left have made the mistake of assuming that Pentecostalism is a reactionary force – and it’s not. It’s actually a hugely important phenomenon of the postmodern city, and of the culture of the urban poor in Latin American and Africa.

BLDGBLOG: Outside of simply filling a void left behind by the retreat of the State, what’s the actual appeal of Pentecostalism for this new generation of urban poor?

Davis: Frankly, one of the great sources of Pentecostalism’s appeal is that it’s a kind of para-medicine. One of the chief factors in the life of the poor today is a constant, chronic crisis of health and medicine. This is partially a result of the World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Programs in the 1980s, which devastated public health and access to medicine in so many countries. But Pentecostalism offers faith healing, which is a major attraction – and it’s not entirely bogus. When it comes to things like addictive behavior, Pentecostalism probably has as good a track record curing alcoholism, neuroses, and obsessions as anything else. That’s a huge part of its appeal. Pentecostalism is a kind of spiritual health delivery system.

BLDGBLOG: It would seem that human overpopulation is, in and of itself, turning cities into slums. In other words, no matter what governmental steps or state-based programs are devised to address urban poverty, slums are just a by-product of overpopulation.

Davis: Well, I don’t actually believe in the notion of overpopulation – particularly as it’s now become clear that the most extreme projections of human population growth just aren’t coming to pass. Probably for the last ten or fifteen years, demographers have been steadily reducing their projections.

The paramount question is not whether the population has grown too large, but: how do you square the circle between, on the one hand, social justice with some kind of equitable right to a decent standard of living, and, on the other, environmental sustainability? There aren’t too many people in the world – but there is, obviously, over-consumption of non-renewable resources on a planetary scale. Of course, the way to square that circle – the solution to the problem – is the city itself. Cities that are truly urban are the most environmentally efficient systems that we have ever created for living together and working with nature. The particular genius of the city is its ability to provide high standards of living through public luxury and public space, and to satisfy needs that can never be meet by the suburban private consumption model.

Having said that, the problem of urbanization in the world today is that it’s not urbanism in the classic sense. The real challenge is to make cities better as cities. I think Planet of Slums addresses the reality that every complaint made by sociologists in the 1950s and 60s about American suburbia is now true on an exponentially increased scale with poor cities: all the problems with sprawl, all the problems with an increasing amount of time and resources tied up in commutes to work, all the problems with environmental pollution, all the problems with the lack of traditional urban apparatuses of leisure, recreation, social services and so on.

BLDGBLOG: Yet a city like Khartoum – or even Cairo – simply doesn’t have the environmental resources to support such a large human population. No matter what the government decides to do, there are simply too many people. Eventually you hit a wall. So there can’t be a European-style social model, based on taxation and the supply of municipal services, if there aren’t the necessary environmental resources.

Davis: Well, I’d say it the other way around, actually. If you look at a city like Los Angeles, and its extreme dependence on regional infrastructure, the question of whether certain cities become monstrously over-sized has less to do with the number of people living there, than with how they consume, whether they reuse and recycle resources, whether they share public space. So I wouldn’t say that a city like Khartoum is an impossible city; that has much more to do with the nature of private consumption.

People talk about environmental footprints, but the environmental footprints of different groups who make up a population tend to differ dramatically. In California, for instance, within the right-wing of the Sierra Club, and amongst anti-immigrant groups, there’s this belief that a huge tide of immigration from Mexico is destroying the environment, and that all these immigrants are actually responsible for the congestion and the pollution – but that’s absurd. Nobody has a smaller environmental footprint, or tends to use public space more intensely, than Latin American immigrants. The real problem is white guys in golf carts out on the hundred and ten golf courses in the Coachella Valley. In other words, one retired white guy my age may be using up a resource base ten, twenty, thirty times the size of a young chicana trying to raise her family in a small apartment in the city.

So Malthusianism, in a crude sense, keeps reappearing in these debates, but the real question is not about panicking in the face of future population growth or immigration, but how to invest in the genius of urbanism. How to make suburbs, like those of Los Angeles, function as cities in a more classical sense. There’s an absolute, essential need to preserve green areas and environmental reserves. A city can’t operate without those. Of course, the pattern everywhere in the world is for poverty – for housing and development – to spill over into crucial watersheds, to build up around reservoirs and open spaces that are essential to the metabolism of the city. Even this astonishing example in Mumbai, where people have pushed so far into the adjacent Sanjay Gandhi National Park that slum dwellers are now being eaten by leopards – or Sao Paulo, which uses astronomical amounts of water purification chemicals because it’s fighting a losing battle against the pollution of its watershed.

If you allow that kind of growth, if you lose the green areas and the open spaces, if you pump out the aquifers, if you terminally pollute the rivers, then, of course, you can do fatal damage to the ecology of the city.

BLDGBLOG: One of the things I found most interesting in your recent book, Monster At Our Door, is the concept of “biosecurity.” Could you explain how biosecurity is, or is not, being achieved on the level of urban space and architectural design?

Davis: I see the whole question of epidemic control and biosecurity being modeled after immigration control. That’s the reigning paradigm right now. Of course, it’s a totally false analogy – particularly when you deal with something like influenza, which can’t be quarantined. You can’t build walls against it. Biosecurity, in a globalized world that contains as much poverty and squalor as our urban world does, is impossible. There is no biosecurity. The continuing quest will be to achieve the biological equivalent of a gated community, with the control of movement and with regulations that just enforce all the most Orwellian tendencies – the selective creation and provision of vaccines, anti-virals, and so on.

But, at the end of the day, biosecurity is an impossibility – until you address the essence of the problem: which is public health for the poor, and the ecological sustainability of the city.

In Monster At Our Door, I cite what I thought was an absolutely model study, published in Science, about how breakneck urbanization in western Africa is occurring at the same time that European factory ships are coming in and scooping up all the fish protein. This has turned urban populations massively to bush meat – which was already a booming business because of construction crews logging out the last tropical forests in west Africa – and, presto: you get HIV, you get ebola, you get unknown plagues. I thought the article was an absolutely masterful description of inadvertent causal linkages, and the complex ecology – the environmental impact – that urbanization has. Likewise, with urbanization in China and southeast Asia, the industrialization of poultry seems to be one of the chief factors behind the threat of avian flu.

As any epidemiologist will tell you, these are just the first, new plagues of globalization – and there will be more. The idea that you can defend against diseases by the equivalent of a gated community is ludicrous, but it’s exactly the direction in which public health policy is being directed. As we’ve seen, unless you’re prepared to shoot down all the migratory birds in the world –

BLDGBLOG: Which I’m sure someone has suggested.

Davis: I mean, I did a lot of calculator work on the UN data, from The Challenge of Slums, calculating urban densities and so on, and this is the Victorian world writ large. Just as the Victorian middle classes could not escape the diseases of the slums, neither will the rich, bunkered down in their country clubs or inside gated communities. The whole obsession now is that avian flu will be brought into the country by –

BLDGBLOG: A Mexican!

Davis: Exactly: it’ll be smuggled over the border – which is absurd. This ongoing obsession with illegal immigration has become a one-stop phantasmagoria for… everything. Of course, it goes back to primal, ancient fears: the Irish brought typhoid, the Chinese brought plague. It’s old hat.

The other thing that’s happening, of course, is that bird flu is being used as a competitive strategy by large-scale, industrialized producers of livestock to force independent producers to the wall. These industrial-scale farms are claiming that only indoor, bio-secured, industrially farmed poultry is safe. This is part of a very complex process of global competition. In Monster At Our Door I cite the case of CP, in Thailand – the Tyson of SE Asia. Even as they’re being wiped-out in Thailand, unable to exploit their chickens, they’re opening new factories in Bulgaria – and profiting from the panic over chicken from Thailand. In other words, avian flu is being used to rationalize and further centralize the poultry industry – yet it appears, to a lot of people, that it’s precisely the industrialization of poultry that has not just allowed the emergence of avian flu but has actually sped up its evolution.

BLDGBLOG: What would a biosecure world actually look like, on the level of architecture and urban design? How do you construct biosecurity? Do you see any evidence that the medical profession is being architecturally empowered, so to speak, influencing the design of “disease-free” public spaces?

Davis: Well, sure. It’s exactly how Victorian social control over the slums was defined as a kind of hygienic project – or in the same way that urban segregation was justified in colonial cities as a problem of sanitation. Everywhere these discourses reinforce one another. What really has been lacking, however, is one big epidemic, originating in poverty, that hits the middle classes – because then you’ll see people really go berzerk. I think one of the most important facts about our world is that middle class people – above all, middle class Americans – have lived inside a historical bubble that really has no precedent in the rest of human history. For two, three, almost four, generations now, they have not personally experienced the cost of war, have not experienced epidemic disease – in other words, they have lived in an ever-increasing arc not only of personal affluence but of personal longevity and security from accidental death, war, disease, and so on. Now if that were abruptly to come to a halt – to be interrupted by a very bad event, like a pandemic, that begins killing some significant number of middle class Americans – then obviously all hell is going to break loose.

The one thing I’m firmly convinced of is that the larger, affluent middle classes in this country will never surrender their lifestyle and its privileges. If suddenly faced with a threat in which they may be made homeless by disaster, or killed by plagues, I think you can expect very, very irrational reactions – which of course will inscribe themselves in a spatial order, and probably in spectacular ways. I think one thing that would emerge after an avian flu pandemic, if it does occur, will be a lot of focus on biosecurity at the level of domestic space.

BLDGBLOG: Duct tape and plastic sheeting.

Davis: Sure.

BLDGBLOG: What has happened to the status or role of the nation-state – of sovereignty, territory, citizenship, etc.? For instance, are national governments being replaced by multinational corporations, and citizens by employees?

Davis: That’s a very interesting question. Clearly, though, what’s happened with globalization has not been the transcendence of the nation-state by the corporation, or by new, higher-level entities. What we’ve seen is much more of a loss of sovereignty on some levels – and the reinforcement of sovereignty on others.

Obviously, the whole process of Structural Adjustment in the 1980s meant the ceding of much local sovereignty and powers of local government to the international bodies that administer debt. The World Bank, for example, working with NGOs, creates networks that often dilute local sovereignty. A brilliant example of this problem is actually what’s happening right now in New Orleans: all the expert commissions, and the oversight boards, and the off-site authorities that are being proposed will basically destroy popular government in New Orleans, reducing the city council to a figurehead and transferring power back to the traditional elite. And that’s all in the name of fighting corruption and so on.

But whether you’ll see new kinds of supra-national entities emerge depends, I think, on the country. Obviously some countries are strengthening their national positions – the state remains all important – while other countries have effectively lost all sovereignty. I mean, look at an extreme case, like Haiti.

BLDGBLOG: How are these shifts being accounted for in the geopolitical and military analyses you mentioned earlier?

Davis: The problem that military planners, and some geopoliticians, are talking about is actually something quite different: that’s the emergence, in hundreds of both little and major nodes across the world, of essentially autonomous slums governed by ethnic militias, gangs, transnational crime, and so on. This is something the Pentagon is obviously very interested in, and concerned about, with Mogadishu as a kind of prototype example. The ongoing crisis of the Third World city is producing almost feudalized patterns of large slum neighborhoods that are effectively terrorist or criminal mini-states – rogue micro-sovereignties. That’s the view of the Pentagon and of Pentagon planners. They also seem quite alarmed by the fact that the peri-urban slums – the slums on the edges of cities – lack clear hierarchies. Even more difficult, from a planning perspective, there’s very little available data. The slums are kind of off the radar screen. They therefore become the equivalent of rain forest, or jungle: difficult to penetrate, impossible to control.

I think there are fairly smart Pentagon thinkers who don’t see this so much as a question of regions, or categories of nation-states, so much as holes, or enclaves within the system. One of the best things I ever read about this was actually William Gibson’s novel Virtual Light. Gibson proposes that, in a world where giant multinational capital is supreme, there are places that simply aren’t valuable to the world economy anymore – they don’t reproduce capital – and so those spaces are shunted aside. A completely globalized system, in Gibson’s view, would leak space – it would have internal redundancies – and one of those spaces, in Virtual Light, is the Bay Bridge.

But, sure, this is a serious geopolitical and military problem: if you conduct basically a triage of the world’s human population – where some people are exiled from the world economy, and some spaces no longer have roles – then you’re offering up ideal opportunities for other people to step in and organize those spaces to their own ends. This is a deeper and more profound situation than any putative conflicts of civilization. It is, in a way, a very unexpected end to the 20th century. Neither classical Marxism, nor any other variety of classical social theory or neoliberal economics, ever predicted that such a large fraction of humanity would live in cities and yet basically outside all the formal institutions of the world economy.

BLDGBLOG: Is there an economic solution, then?

Davis: You’ll never re-conquer these parts of the city simply through surveillance, or military invasion, or policing – you have to offer the people some way to re-connect with the world economy. Until you can provide resources, or jobs, the danger is that this will worsen. People are being thrown back onto tribal and ethnic clientelism of one kind or another as a means of survival – even as a means of excluding other poor people from these already limited resources. Increasingly, new arrivals in the city – the sons and daughters of the urban poor – are being pressed by tighter housing markets, and by the inability to find cheap – certainly not free – land. Where cheap land does exist, it only exists because the land is otherwise undevelopable. It’s too dangerous. You’re just wagering on natural disaster. In fact, the end of this frontier of squattable land is one conclusion of Planet of Slums.

Another conclusion is that almost all the research on informal urban economies has shown that informality is simply not generating job ladders. Sure, some micro-entrepreneurs go on to become mini-entrepreneurs – but the larger fact is you’re just subdividing poverty. You’re getting more and more people competing, trying to pursue the same survival strategies in the same place. Those are the facts that darken this book the most, I think. They’re also what darken the horizon of research on the city in general, even more than questions of sanitation and so on. What the World Bank, what the NGOs, what all the apostles of neoliberal self-help depend on is the availability of cheap, squattable land, and the existence of entrepreneurial opportunities in the informal sector.

If you exhaust those two, people will be driven to the wall – and then the safety valves won’t work. Then the urban poor will run out of the resources for miracles.

BLDGBLOG: I’ll wrap up with two quick questions. It’s interesting that you’re raising a family – even two young toddlers – in a world where, as you write, there are emerging super-plagues, earthquakes, race riots, tornadoes in Los Angeles, mega-slums, etc. Are you nervous about the future for your kids?

Davis: Well, of course. I mean, people who read into my work a kind of delight in disaster and apocalypse either are reading incorrectly or I’m a bad writer – because that isn’t the intention. To be honest with you, there’s more of a yearning for these kinds of apocalypse in the literature of Pentecostalism –

BLDGBLOG: Good point.

Davis: – and that’s apocalypse properly understood, its real, Biblical meaning. It’s precisely this idea of an unrevealed, secret history of the world that will become luminously clear in the last hour, and will rewrite history from the standpoint of the people who had previously been history’s victims. I would say that, as somebody who’s ultimately an old-fashioned socialist, or rationalist, with an almost excessive faith in science – you know, I tremble when I write this stuff. I take no joy in writing a book about car bombs, but it just struck me that here was this technology nobody had written about on its own terms, yet it had become horribly successful. It’s a lot easier for me to cope with hypochondria about avian flu – having written a book about it – than if I hadn’t written about it. Let’s put it that way. I feel the same way about the future of my children.

BLDGBLOG: Finally, have you ever considered working outside the genre of critical nonfiction, and – in an almost Ridley Scott-like way – directing a film, or writing a novel?

Davis: [laughs] Well, I have in an extremely minor way: I’ve published two young adult science adventure novels – which is the name I’ve given to the genre – through Viggo Mortenson’s little press, Perceval Press. Three young kids, including my son who lives in Dublin, are the heroes.

BLDGBLOG: How’d that come about?

Davis: It all arose out of the fact that, in 1998, I got this MacArthur Foundation money – and I just wasted it all [laughter]. My kids and I went to the four corners of the earth. I took my son to east Greenland, and one night – because the sun never sets, and the sled dogs howl into the wee hours – he asked me to tell him a story, and I spun it off into a novel. But that’s as far as I’ll get. I mean, living in LA as long as I have, the one thing you learn is: stay away from Hollywood. Never, ever contemplate writing a screenplay or getting involved in a movie; it’s just a graveyard of talented people. I’ve literally seen the best minds of my generation destroyed by the allure of that kind of stuff. And I’ve never had the slightest desire to do it. If I wrote fiction it would be very forgettable.

BLDGBLOG: So if Ridley Scott called you in to write his next screenplay you’d have to refuse?

Davis: I’ve seen people I admire greatly – hugely talented, much greater writers than I am – just crash and burn and destroy their lives: partially because they never learned the difference between good writing and Hollywood. It’s the same way with the seduction of becoming a public intellectual, having lots of fans, and reading in bookstores all the time – which I’ve learned to run away from with horror. Right now I’m trying to simplify my life by cutting out as much of that stuff as possible, because I’m having a ball with my two two-year olds, hanging out in Balboa Park everyday.

(BLDGBLOG owes an enormous thanks to Mike Davis for his time, patience, and willingness to see this discussion through to completion. All drawings used in this interview are by Leah Beeferman – who also deserves a big thanks. Don’t miss part one).

[Image: Photo by m.joedicke, via Border Town].

[Image: Photo by m.joedicke, via Border Town].

[Image: U.S./Mexico border marker #184; photograph by

[Image: U.S./Mexico border marker #184; photograph by  [Image: The Dariel Pass in the Caucausus Mountains, rumored possible site of the mythic

[Image: The Dariel Pass in the Caucausus Mountains, rumored possible site of the mythic  [Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, mythic isotope to Alexander’s Gates].

[Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, mythic isotope to Alexander’s Gates]. [Image: The geography of Us vs. Them, in a “12th century map by the Muslim scholar Al-Idrisi. ‘Yajooj’ and ‘Majooj’ (Gog and Magog) appear in Arabic script on the bottom-left edge of the Eurasian landmass, enclosed within dark mountains, at a location corresponding roughly to Mongolia.” Via

[Image: The geography of Us vs. Them, in a “12th century map by the Muslim scholar Al-Idrisi. ‘Yajooj’ and ‘Majooj’ (Gog and Magog) appear in Arabic script on the bottom-left edge of the Eurasian landmass, enclosed within dark mountains, at a location corresponding roughly to Mongolia.” Via  [Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, via

[Image: Constructing the wall of Dhul-Qarnayn, via  [Image: A map of the

[Image: A map of the  [Image: Airfield at Guantanamo Bay converted for the quarantine of 10,000 Haitian migrants; via

[Image: Airfield at Guantanamo Bay converted for the quarantine of 10,000 Haitian migrants; via  [Image:

[Image:  [Images: Asian immigrants arriving at the Angel Island immigration station, San Francisco, and a man quarantined at Ellis Island; courtesy of the

[Images: Asian immigrants arriving at the Angel Island immigration station, San Francisco, and a man quarantined at Ellis Island; courtesy of the  [Image: “Testing an Asian immigrant” at the Angel Island immigration station, San Francisco; courtesy of the

[Image: “Testing an Asian immigrant” at the Angel Island immigration station, San Francisco; courtesy of the  [Image: Medical inspection station at Ellis Island. The 1891 U.S. immigration law called for the exclusion of “all idiots, insane persons, paupers or persons likely to become public charges, persons suffering from a loathsome or dangerous contagious disease,” as well as criminals. Courtesy of the

[Image: Medical inspection station at Ellis Island. The 1891 U.S. immigration law called for the exclusion of “all idiots, insane persons, paupers or persons likely to become public charges, persons suffering from a loathsome or dangerous contagious disease,” as well as criminals. Courtesy of the  [Image: Isolation Section,

[Image: Isolation Section,  [Image: A “Quarantine Act” banner from the Torrens Island Quarantine Station collection, held by the

[Image: A “Quarantine Act” banner from the Torrens Island Quarantine Station collection, held by the  [Image: View through the perimeter fence at Port Hedland Immigration Reception and Processing Centre in Western Australia, June 2002, from the

[Image: View through the perimeter fence at Port Hedland Immigration Reception and Processing Centre in Western Australia, June 2002, from the  [Image: Thermal scanners at the Seoul international airport; photo by Jung Yeon-Je for Reuters, via

[Image: Thermal scanners at the Seoul international airport; photo by Jung Yeon-Je for Reuters, via  [Image: Map of

[Image: Map of

[Images: (top) The North Head Quarantine Station, Manly, Australia; photo by

[Images: (top) The North Head Quarantine Station, Manly, Australia; photo by  [Image: As Egypt and Sudan gained their independence from Britain, the border between the two countries was determined by drawing a straight line from the sea through

[Image: As Egypt and Sudan gained their independence from Britain, the border between the two countries was determined by drawing a straight line from the sea through  [Images:

[Images:  [Image: An Italian Health Passport, via the

[Image: An Italian Health Passport, via the  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: The

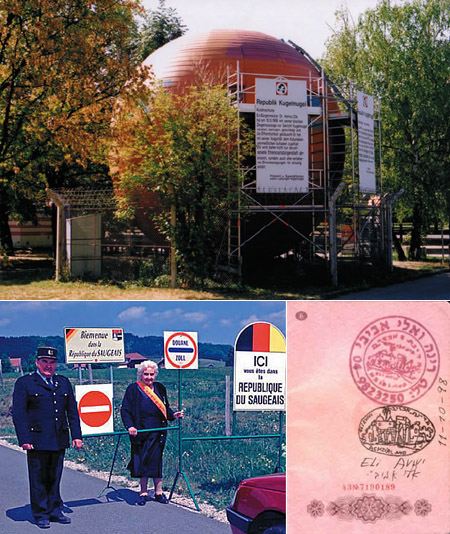

[Image: The  [Image: The strange, island-like spaces of micro-sovereignty within the town of

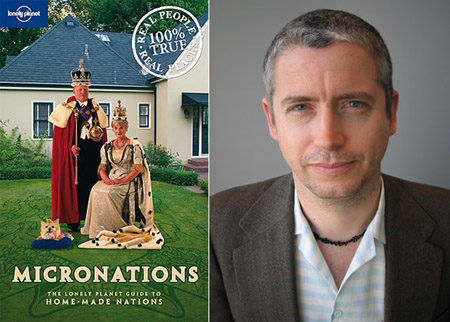

[Image: The strange, island-like spaces of micro-sovereignty within the town of  [Images: The book and one of its authors,

[Images: The book and one of its authors,  [Image:

[Image:  [Images: The

[Images: The  [Images: Kevin Baugh, President of the

[Images: Kevin Baugh, President of the  [Images: Emperor Georgius II of the

[Images: Emperor Georgius II of the