[Image: Daniel Dociu. View larger! This and all images below are Guild Wars content and materials, and are trademarks and/or copyrights of ArenaNet, Inc. and/or NCsoft Corporation, and are used with permission; all rights reserved].

[Image: Daniel Dociu. View larger! This and all images below are Guild Wars content and materials, and are trademarks and/or copyrights of ArenaNet, Inc. and/or NCsoft Corporation, and are used with permission; all rights reserved].

Seattle-based concept artist Daniel Dociu is Chief Art Director for ArenaNet, the North American wing of NCSoft, an online game developer with headquarters in Seoul. Most notably, Dociu heads up the production of game environments for Guild Wars – to which GameSpot gave 9.2 out of 10, specifically citing the game’s “gorgeous graphics” and its “richly detailed and shockingly gigantic” world.

Dociu has previously worked with Electronic Arts; he has an M.A. in industrial design; and he won both Gold and Silver medals for Concept Art at this year’s Spectrum awards

To date, BLDGBLOG has spoken with novelists, film editors, musicians, architects, photographers, historians, and urban theorists, among others, to see how architecture and the built environment have been used, understood, or completely reimagined from within those disciplines – but coverage of game design is something in which this site has fallen woefully short.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

So when I first saw Daniel Dociu’s work I decided to get in touch with him, and to ask him some questions about architecture, landscape design, and the creation of detailed online environments for games.

For instance, are there specific architects, historical eras, or urban designers who have inspired Dociu’s work? What about vice versa: could Dociu’s own beautifully rendered take on the built environment, however fantastical it might be, have something to teach today’s architecture schools? How does the game design process differ from – or perhaps resemble – that of producing “real” cities and buildings?

Of course, there are many types of games, and many types of game environments. The present interview focuses quite clearly on fantasy – and it does so not from the perspective of game play or of programming but from the visual perspective of architectural design.

After all, if Dociu’s buildings and landscapes are spaces that tens of thousands of people have experienced – far more than will ever experience whatever new home is featured in starchitects’ renderings cut and pasted from blog to blog this week – then surely they, too, should be subject to architectural discussion?

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

Further, at what point in the design process do architects themselves begin to consider action and narrative development – and would games be a viable way for them to explore the social use of their own later spaces?

What would a game environment designed by Rem Koolhaas, or Zaha Hadid, or FAT really look like – and could video games be an interesting next step for professional architectural portfolios? You want to see someone’s buildings – but you don’t look at a book, or at a PDF, or at a Flickr set of JPGs: you instead enter an entire game world, stocked only with spaces those architects have created.

Richard Rogers is hired to design Grand Theft Auto: South London.

Of course, these questions go far beyond the scope of this interview – but such a discussion would be well worth having.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

What appears below is an edited transcript of a conversation I had with Daniel Dociu about his work, and about the architecture of game design.

• • • [Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

BLDGBLOG: First, I’d love to hear where you look for inspiration or ideas when you sit down to work on a project. Do you look at different eras of architecture, or at specific buildings, or books, or paintings – even other video games?

Daniel Dociu: Anything but video games! [laughs] I don’t want to copy anybody else.

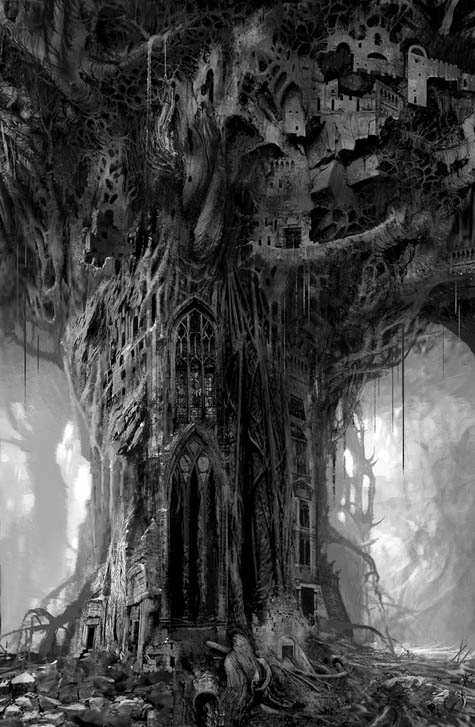

Architecture has always made a strong impression on me – though I can’t think of one particular style or era or architect where I would say: “This is it. This is the one and only influence that I’ll let seep into my work.” Rather, I just sort of store in my memory everything that has ever made an impression on me, and I let it simmer there and blend with everything else. Eventually some things will resurface and come back, depending on the particular assignment I’m working on.

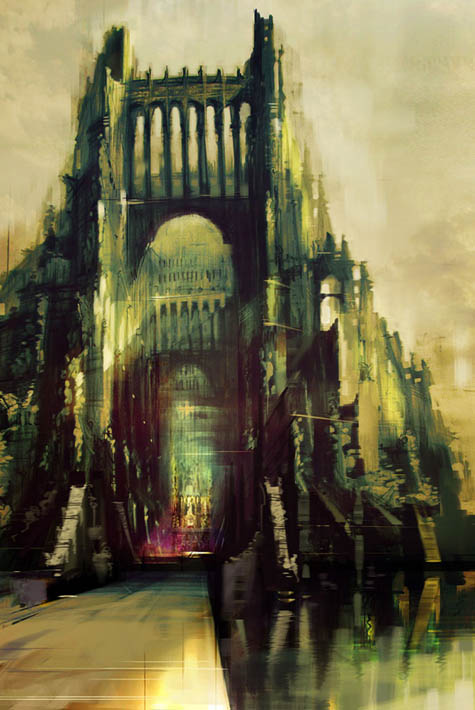

But I look back all the way to the dawn of mankind: to ruins, and Greek architecture, and Mycenean architecture, all the way up to the architecture of the Crusades, and castles in North Africa, and the Romanesque and Gothic and Baroque and Rococo – even to neo-Classical and art deco and Bauhaus and Modernist. I mean, there are bits and pieces here and there that make a strong impression on me, and I blend them – but that’s the beauty of games. You don’t have to be stylistically pure, or even coherent. You can afford a certain eclecticism to your work. It’s a more forgiving medium. I can blend elements from the Potala Palace in Tibet with, say, La Sagrada Família, Antoni Gaudí’s cathedral. I really take a lot of liberties with whatever I can use, wherever I can find it.

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: top, middle, and bottom].

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: top, middle, and bottom].

BLDGBLOG: Of course, if you were an architecture student and you started to design buildings that looked like Gothic cathedrals crossed with the Bauhaus, everybody outside of architecture school might love it, but inside your studio –

Dociu: You’d be crucified! [laughs]

[Image: Daniel Dociu; larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; larger!].

BLDGBLOG: No one would take you seriously. It’d be considered unimaginative – even kitsch.

Dociu: Absolutely. That’s probably why I chose to work in this field. There’s just so much creative freedom. I mean, sure, you do compromise and you do tailor your ideas, and the scope of your design, to the needs of the product – but, still, there’s a lot of room to push.

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: top and bottom].

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: top and bottom].

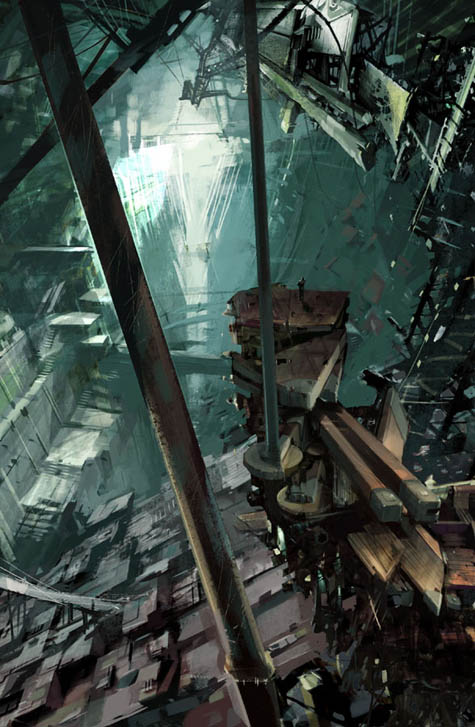

BLDGBLOG: So how much description are you actually given? When someone comes to you and says, “I need a mine, or a mountain, or a medieval city” – how much detail do they really give before you have to start designing?

Dociu: That’s about the amount of information I get.

Game designers lay things out according to approximate locations – this tribe goes here, this tribe goes there, we need a village here, we need an extra reason for a conflict along this line, or a natural barrier here, whether it’s a river or a mountain, or we need an artificial barrier or a bridge. That’s pretty much the level at which I prefer for them to give me input, and I take it from there. Most of my work recently has been focusing around environments and unique spaces that fulfill whatever the game play requires – providing a memorable background for that experience.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

BLDGBLOG: So somebody just says, “we need a castle,” and you go design it?

Dociu: Usually I don’t put pen to paper, figuratively speaking, until I have an idea. I don’t believe in just doodling and hoping for things to happen. More often than not, I think about a sentiment or an emotion that I’m trying to capture with an environment – and then I go back in my mind through images or places that have made a strong impression on me, and I see if anything resonates. I then start doing research along those lines. Only once did I have a pretty strong formal solution – an actual design or spatial relationship, an architectural arrangement of the elements – before that emotion crystallized.

But do I want something to be awe-inspiring, daunting, unnerving? That’s what I work on first – to have that sentiment clarify itself. I don’t start just playing with shapes to see what might result. Most of my work is pretty simple, so clarity and simplicity is important to me; my ideas aren’t very sophisticated, as far as requiring complex technical solutions. They’re pretty simple. I try to achieve emotional impact through rather simple means.

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: one, two, three, four, five, and six].

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: one, two, three, four, five, and six].

BLDGBLOG: Do you ever find that you’ve designed something where the architecture itself sort of has its own logic – but the logic of the game calls for something else? So you have to design against your own sense of the design for the sake of game play?

Dociu: Oh, absolutely – more often than not.

To make an environment work for a game, you have to redesign your work – and I do sometimes feel bad about the missed opportunities. These may not be ideas that would necessarily make great architecture in real life, but these ideas often take a more uncompromising form – a more pure form – before you have to change them. When these environments need to be adapted to the game, they lose some of that impact.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

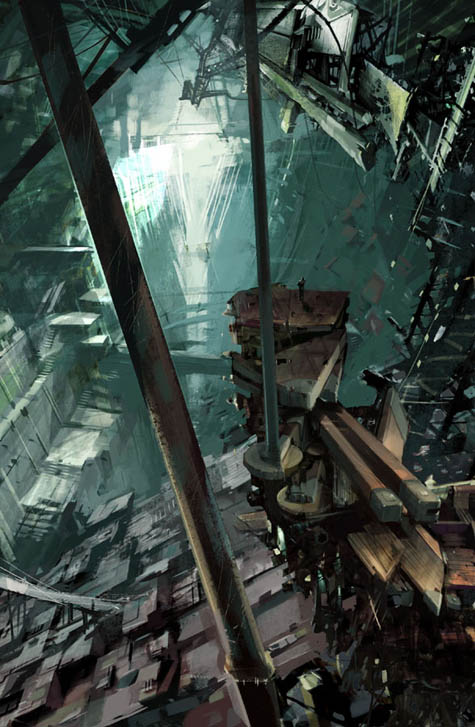

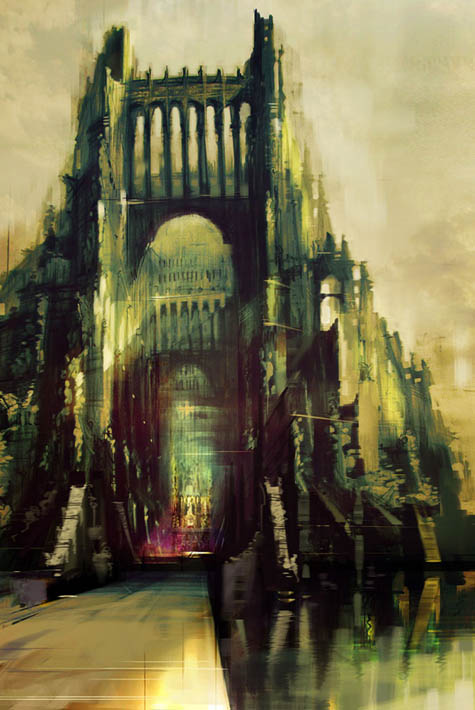

BLDGBLOG: I’d love to focus on a few specific images now, to hear what went into them – both conceptually and technically. For instance, the image I’m looking at here is called Skybridge. Could you tell me a little bit more about that?

Dociu: Sure. The request there was for a tribe that’s been trying to isolate itself from the conflict, and the tensions, and the political unrest of the world around it. So they find this canyon in the mountains – and I was picturing the mountains kind of like the Andes: really steep and shard-like. They pick one of these canyons and they build a structure that’s floating above the valley below – to physically remove themselves from the world. That was the premise.

I wanted a structure that looked light and airy, as if it’s trying to float, and I chose the shapes you see for their wing-like quality. Everything is very thin, supported by a rather minimalist structure of cables. It’s supposed to be the habitat for an entire tribe that chooses to detach themselves from society, as much as they can.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

BLDGBLOG: You’ve designed a lot of structures in the sky, like airborne utopias – for instance, the Floating Mosque and the Floating Temple. Was there a similar concept behind those images?

Dociu: Well, yes and no. The reasons behind those examples were quite different. First, floating mosques were my attempt to deal with what is a rather obnoxious cliché in games – which is floating castles. Every game has a floating castle. You know, I really hate that!

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

BLDGBLOG: [laughs] So these are actually your way of dealing with a game design cliché?

Dociu: I was trying to find a somewhat elegant and satisfying solution to an uninteresting request.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

BLDGBLOG: And what about Pagodas?

Dociu: The story there was that this was a city for the elite. It was built in a pool of water and it was surrounded by desert. Water is in really high demand in this world, but these guys are kind of controlling the water supply. The real estate on these rock formations is limited, though, so they were forced to build vertically and use every inch of rock to anchor their structures. So it’s about people over-building, and about clinging onto resources, and about greed.

That doesn’t touch on the game in its entirety – but that’s the story behind the image.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

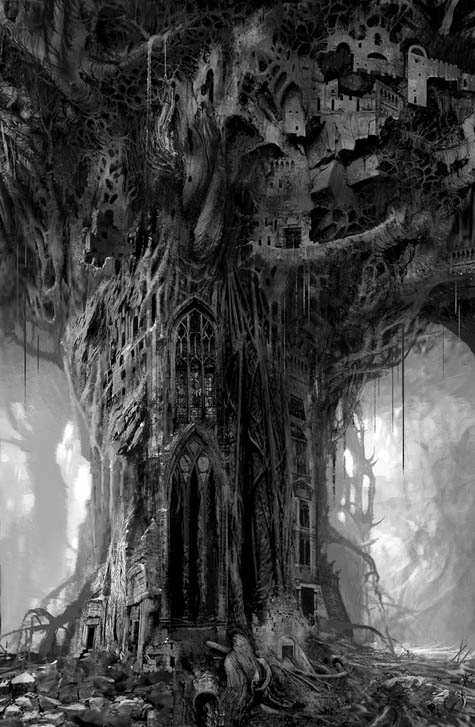

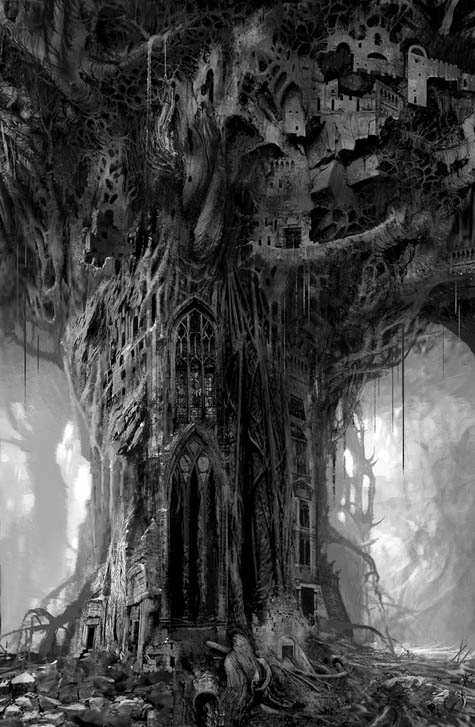

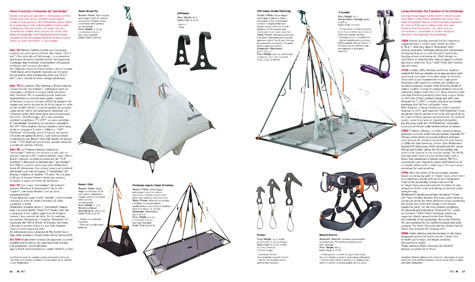

BLDGBLOG: Finally, what about the Petrified Tree?

Dociu: That was part of another chapter in our game. We thought that there should be some kind of cataclysm – or an event, a curse – that turns the oceans into jade and the forests into stone. We had nomads traveling the jade sea in these big contraptions, like machines.

So the petrified forest was a gigantic forest that got turned into stone, and the people who were happily inhabiting that forest had to find ways to carve dwellings into the trees: different ways of shaping the natural stone formations and giving them some kind of functionality – arches, bridges, dwellings, and so on and so forth. It was a blend of organic and manmade structures.

At that particular point in time, quite a few of my pieces were the result of my fascination with the Walled City of Kowloon. I was really sad to see that demolished, and this was kind of my desperate attempt to hold onto it! I was incorporating that sensibility into a lot of my pieces, knowing it was going to be gone for good.

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: top and bottom].

[Images: Daniel Dociu; view larger: top and bottom].

• • •Thanks again to Daniel Dociu for taking the time to have this conversation. Meanwhile, many, many more images are available on his website – and in this

Flickr set.

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

[Image: Daniel Dociu; view larger!].

(Daniel Dociu’s work originally spotted on io9).

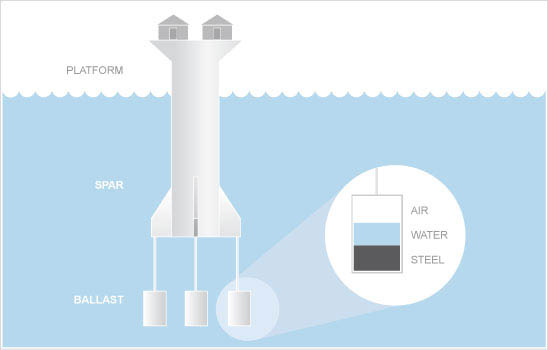

[Image: Illustration by Holl Liou, courtesy of Wired].

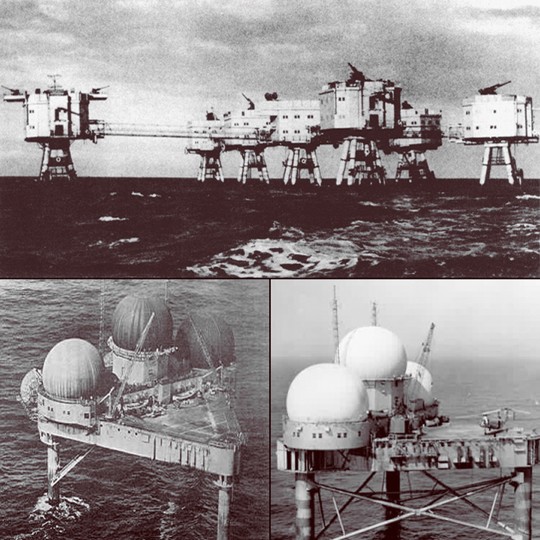

[Image: Illustration by Holl Liou, courtesy of Wired]. [Images: The Maunsell Towers (top), unmentioned by the libertarian seasteaders, and the Texas Tower (bottom)].

[Images: The Maunsell Towers (top), unmentioned by the libertarian seasteaders, and the Texas Tower (bottom)]. [Image: Tapping into oceanic motion with BioPower Systems].

[Image: Tapping into oceanic motion with BioPower Systems]. [Images:

[Images:  [Images: Three examples of maps displayed on

[Images: Three examples of maps displayed on

[Image: From the series

[Image: From the series

[Image: “

[Image: “ [Image: A map of the

[Image: A map of the  [Image: Vertical House by

[Image: Vertical House by  [Image: Vertical House by

[Image: Vertical House by  [Image: From an article by

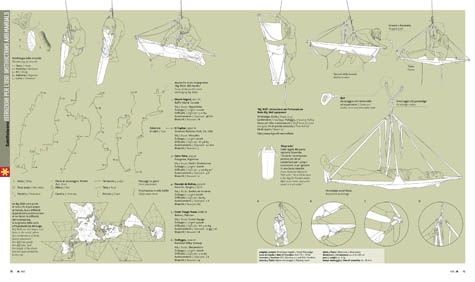

[Image: From an article by  [Image: Another spread from

[Image: Another spread from  [Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The

[Images: Two spreads from

[Images: Two spreads from  [Image: Spatial City by Yona Friedman: “The framework was to be erected first, and the residences conceived and built by the inhabitants inserted into the voids of the structure.” Courtesy of the

[Image: Spatial City by Yona Friedman: “The framework was to be erected first, and the residences conceived and built by the inhabitants inserted into the voids of the structure.” Courtesy of the  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: Felix Hess assembles similar sound machines, next to a photo of an unrelated concert hall].

[Image: Felix Hess assembles similar sound machines, next to a photo of an unrelated concert hall]. [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: Ice in Cranberry Lake, Ontario, photographed by Michael Runtz; via

[Image: Ice in Cranberry Lake, Ontario, photographed by Michael Runtz; via

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Images: From

[Image: From

[Image: From