[Image: “Looking east over unbuilt Ascaya lots, Black Mountain beyond, Henderson, Nevada,” 2010; from Black Mountain by Michael Light].

[Image: “Looking east over unbuilt Ascaya lots, Black Mountain beyond, Henderson, Nevada,” 2010; from Black Mountain by Michael Light].

Photographer Michael Light has a new book coming out this fall, published by Radius Books, with work documenting the construction and large-scale terrestrial formatting of two housing developments in the American southwest, one unfinished, one gaudily over the top.

They are known as Ascaya and Lake Las Vegas.

[Image: “Unbuilt Ascaya lots and cul-de-sac looking west, Henderson, Nevada,” 2011; from Black Mountain by Michael Light].

[Image: “Unbuilt Ascaya lots and cul-de-sac looking west, Henderson, Nevada,” 2011; from Black Mountain by Michael Light].

Ascaya was meant to ascend into the desert hills like a vast residential staircase, its plots patiently shaped and awaiting their architecture—but these ambitious plans were radically decelerated into a state of suspended animation by the economic collapse of 2008.

It is now something more like a stalled earthwork, a vast land art installation made all the more amazing when seen from above.

[Image: “Unbuilt Ascaya lots and culdesac looking northwest, Sun City MacDonald Ranch development beyond, Henderson, Nevada,” 2012; from Black Mountain by Michael Light].

[Image: “Unbuilt Ascaya lots and culdesac looking northwest, Sun City MacDonald Ranch development beyond, Henderson, Nevada,” 2012; from Black Mountain by Michael Light].

The resulting landforms—huge berms, winding streets, flat-capped foundation piles, and carefully graded podiums of dirt and gravel—look at times like hard drive platters, chocolate bars, or even the tailings piles of a colossal mine.

This latter comparison was made by Light himself in a long interview Nicola Twilley and I recorded with him for Venue.

There, Light told us that “the more work I do in Las Vegas, the more I see parallels between the mining industry—and the extraction history of the west—and the inhabitation industry.”

They do the same sort of things to the land; they grade, flatten, and format the land in similar ways. It can be hard to tell the difference sometimes between a large-scale housing development being prepped for construction and a new strip mine where some multinational firm is prospecting for metals.

“In other words,” he continued, “the extraction industry and the inhabitation industry are two sides of the same coin. The terraforming that takes place to make a massive development on the outskirts of a city has the same order, and follows the same structure, as much of the terraforming done in the process of mining.”

[Images: (top) “The Falls at Lake Las Vegas construction road looking north, Henderson, Nevada,” 2011; (bottom) “Future house lots and abandoned mattress at The Falls at Lake Las Vegas, looking west, Henderson, Nevada,” 2011; both from Lake Las Vegas by Michael Light].

[Images: (top) “The Falls at Lake Las Vegas construction road looking north, Henderson, Nevada,” 2011; (bottom) “Future house lots and abandoned mattress at The Falls at Lake Las Vegas, looking west, Henderson, Nevada,” 2011; both from Lake Las Vegas by Michael Light].

“That was a revelation for me,” Light added. “The mine is a city reversed. It is its own architecture.”

The mine is a city reversed.

[Images: “Unbuilt Ascaya lots looking northwest, Henderson, Nevada,” 2012; both from Black Mountain by Michael Light].

[Images: “Unbuilt Ascaya lots looking northwest, Henderson, Nevada,” 2012; both from Black Mountain by Michael Light].

“Until 2008,” the book’s accompanying press release explains, “Nevada was the fastest-growing state in America. But the recession stopped this urbanizing gallop in the Mojave Desert, and Las Vegas froze at exactly the point where its aspirational excesses were most baroque and unfettered.”

They call these homes “castles on the cheap,” and one look at the houses of Lake Las Vegas reveals how apt this comparison can be.

[Image: “V At Lake Las Vegas pool complex, Via Visione at left, Henderson, Nevada,” 2010; from Lake Las Vegas by Michael Light].

[Image: “V At Lake Las Vegas pool complex, Via Visione at left, Henderson, Nevada,” 2010; from Lake Las Vegas by Michael Light].

In one of the book’s two essays, veteran landscape activist Lucy Lippard writes that the images offer “a disturbing juxtaposition of geologic and current time that the Surrealists could only have imagined.”

[Image: “Monaco Lake Las Vegas home and foreclosed neighbor, on guard-gated Grand Corniche Drive, Henderson, Nevada,” 2010; from Lake Las Vegas by Michael Light].

[Image: “Monaco Lake Las Vegas home and foreclosed neighbor, on guard-gated Grand Corniche Drive, Henderson, Nevada,” 2010; from Lake Las Vegas by Michael Light].

Honestly, these shots blow me away; it’s as if Light has captured an act of topographical blackout—a whole landscape, redacted—as what should be hills and valleys are erased and obstructed by this imposed crystallography of settlements that never arrived.

[Image: “Ascaya Boulevard looking south up Black Mountain, morning, Henderson, Nevada,” 2012; from Black Mountain by Michael Light].

[Image: “Ascaya Boulevard looking south up Black Mountain, morning, Henderson, Nevada,” 2012; from Black Mountain by Michael Light].

In any case, the forthcoming book is already generating quite a bit of buzz—for example, being chosen as one of the “Best Fall Photo Books” of 2014 by Time Magazine.

[Images: Some shots of the books, which are actually bound together, back-to-back].

[Images: Some shots of the books, which are actually bound together, back-to-back].

The reproductions look fantastic, as well; consider pre-ordering a copy (and, while you’re at it, consider reading our interview with Michael Light over at Venue).

The book comes out somewhat appropriately on Halloween—a kind of economic horror story of landscapes gone awry.

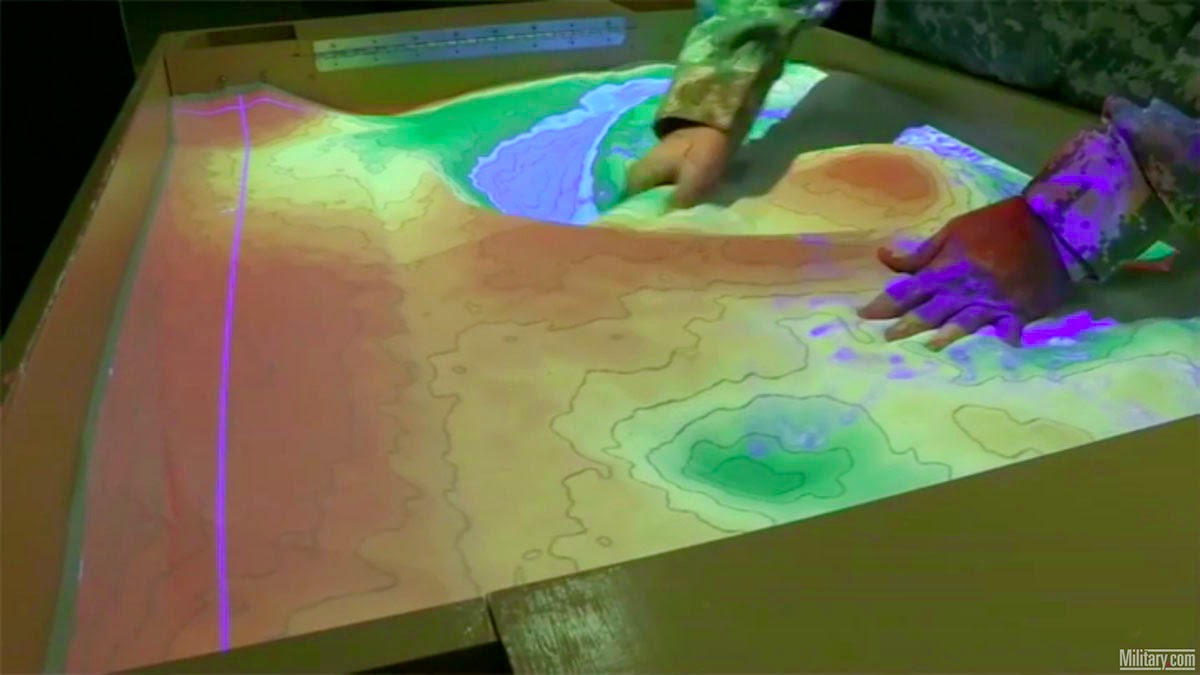

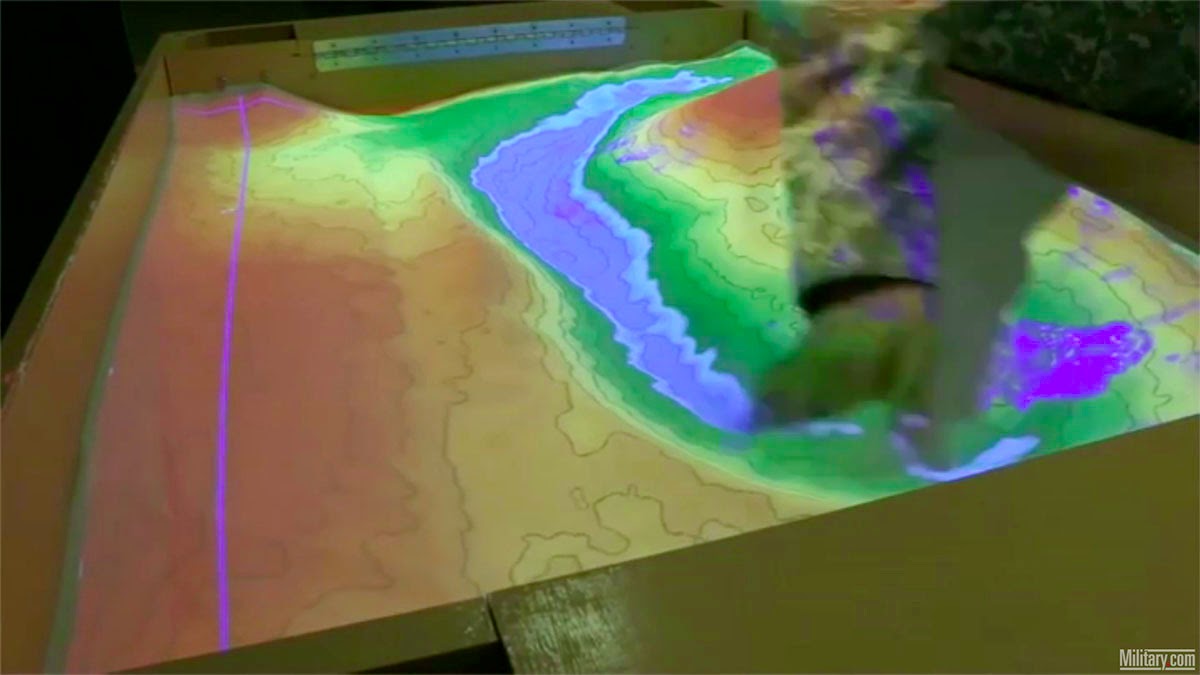

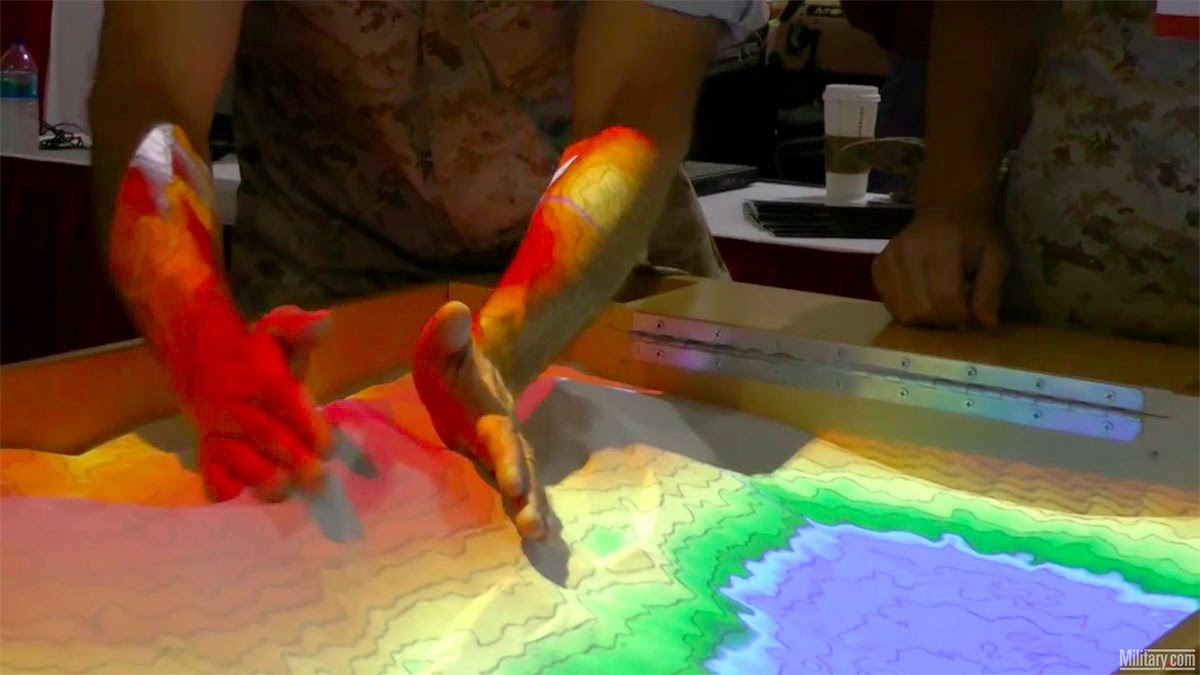

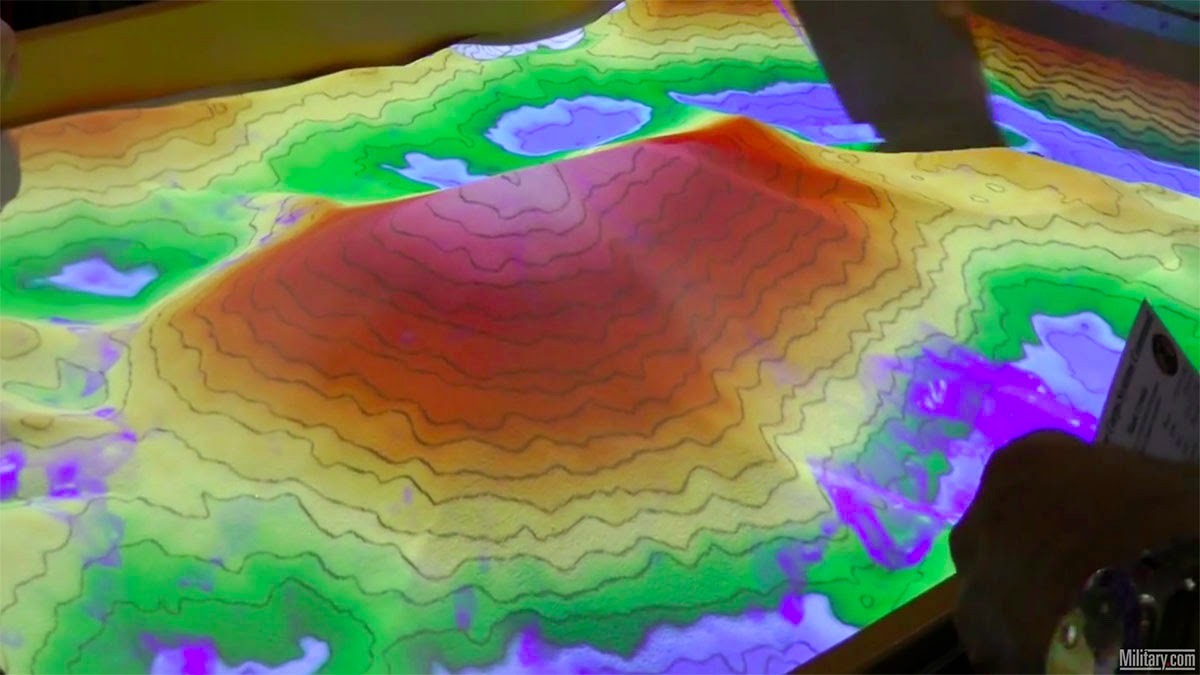

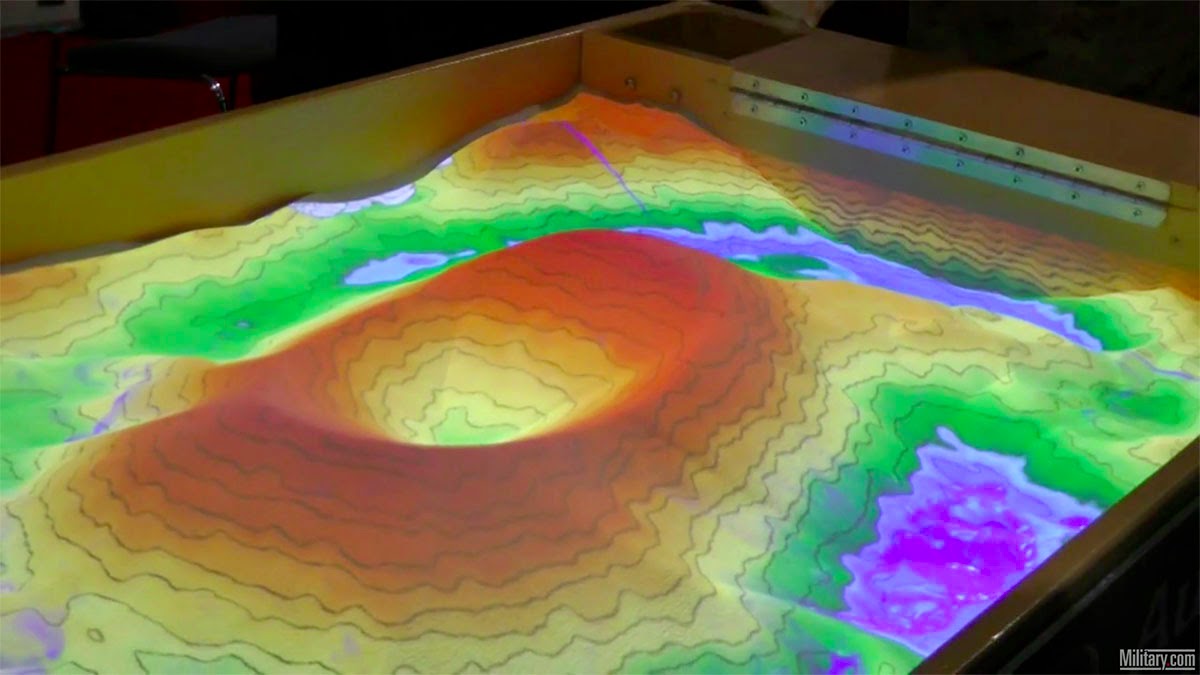

[Image: Screen grab via military.com].

[Image: Screen grab via military.com].

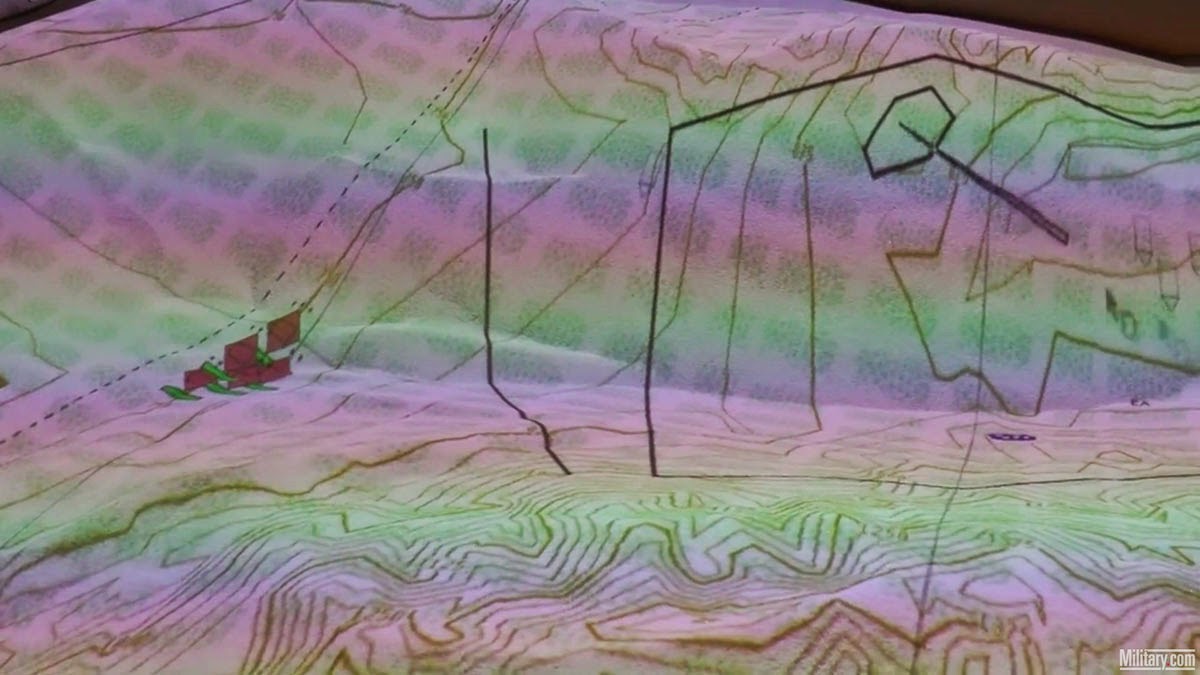

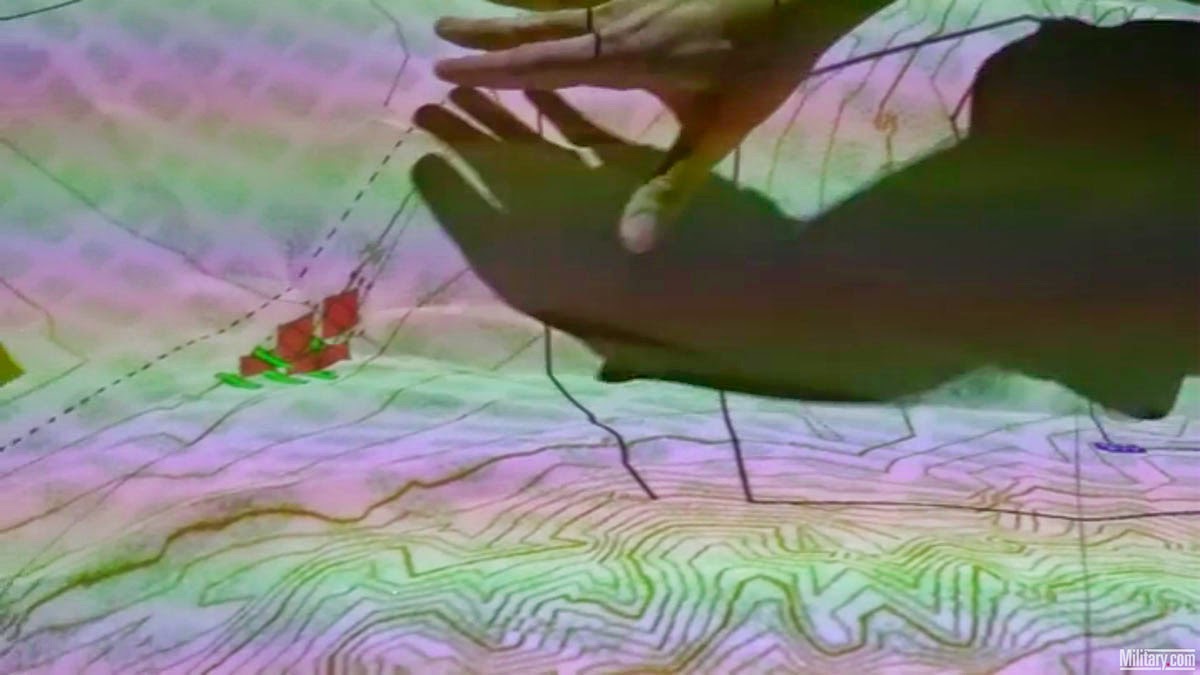

[Image: Screen grabs via military.com].

[Image: Screen grabs via military.com].

[Image: Screen grabs via military.com].

[Image: Screen grabs via military.com].

[Image: Screen grabs via military.com].

[Image: Screen grabs via military.com].

[Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: Tokyo subway map, via

[Image: Tokyo subway map, via

[Image: Real estate development or avant-garde earthwork? The future streets of

[Image: Real estate development or avant-garde earthwork? The future streets of  [Image: Another view of the abstract landforms of

[Image: Another view of the abstract landforms of  [Image: One more glimpse of

[Image: One more glimpse of

[Image: “Looking east over unbuilt Ascaya lots, Black Mountain beyond, Henderson, Nevada,” 2010; from Black Mountain by

[Image: “Looking east over unbuilt Ascaya lots, Black Mountain beyond, Henderson, Nevada,” 2010; from Black Mountain by  [Image: “Unbuilt Ascaya lots and cul-de-sac looking west, Henderson, Nevada,” 2011; from Black Mountain by

[Image: “Unbuilt Ascaya lots and cul-de-sac looking west, Henderson, Nevada,” 2011; from Black Mountain by  [Image: “Unbuilt Ascaya lots and culdesac looking northwest, Sun City MacDonald Ranch development beyond, Henderson, Nevada,” 2012; from Black Mountain by

[Image: “Unbuilt Ascaya lots and culdesac looking northwest, Sun City MacDonald Ranch development beyond, Henderson, Nevada,” 2012; from Black Mountain by

[Images: (top) “The Falls at Lake Las Vegas construction road looking north, Henderson, Nevada,” 2011; (bottom) “Future house lots and abandoned mattress at The Falls at Lake Las Vegas, looking west, Henderson, Nevada,” 2011; both from Lake Las Vegas by

[Images: (top) “The Falls at Lake Las Vegas construction road looking north, Henderson, Nevada,” 2011; (bottom) “Future house lots and abandoned mattress at The Falls at Lake Las Vegas, looking west, Henderson, Nevada,” 2011; both from Lake Las Vegas by  [Images: “Unbuilt Ascaya lots looking northwest, Henderson, Nevada,” 2012; both from Black Mountain by

[Images: “Unbuilt Ascaya lots looking northwest, Henderson, Nevada,” 2012; both from Black Mountain by  [Image: “V At Lake Las Vegas pool complex, Via Visione at left, Henderson, Nevada,” 2010; from Lake Las Vegas by

[Image: “V At Lake Las Vegas pool complex, Via Visione at left, Henderson, Nevada,” 2010; from Lake Las Vegas by  [Image: “Monaco Lake Las Vegas home and foreclosed neighbor, on guard-gated Grand Corniche Drive, Henderson, Nevada,” 2010; from Lake Las Vegas by

[Image: “Monaco Lake Las Vegas home and foreclosed neighbor, on guard-gated Grand Corniche Drive, Henderson, Nevada,” 2010; from Lake Las Vegas by  [Image: “Ascaya Boulevard looking south up Black Mountain, morning, Henderson, Nevada,” 2012; from Black Mountain by

[Image: “Ascaya Boulevard looking south up Black Mountain, morning, Henderson, Nevada,” 2012; from Black Mountain by

[Images: Some shots of the books, which are actually bound together, back-to-back].

[Images: Some shots of the books, which are actually bound together, back-to-back].

[Image: From the original research paper (

[Image: From the original research paper (