[Image: Building the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor; ©ITER Organization].

[Image: Building the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor; ©ITER Organization].

An artificially excavated limestone pit in the south of France will soon host star-making technology, New Scientist reports. “If all goes well,” the magazine explains, in a few year’s time the pit will “rage with humanity’s first self-sustaining fusion reaction, an artificial sun ten times hotter than the one that gives our planet life.”

[Image: Building the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor; ©ITER Organization].

[Image: Building the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor; ©ITER Organization].

Reaching that point, however, requires an ambitious reformatting of the entire site, seemingly the very limit of landscape architecture: a kind of concrete garden that produces stars.

As the project now stands, construction involves inserting a supergrid of rebar into the quarried pit, securing the limestone walls with concrete foundation work, then pouring seismically-stabilized plinths that will support the so-called International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (or ITER) upon completion.

[Image: Checking plinths at the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, as if Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial in Berlin could be repurposed for building stars. Photo ©ITER Organization].

[Image: Checking plinths at the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, as if Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial in Berlin could be repurposed for building stars. Photo ©ITER Organization].

Superficially—i.e. they’re both in France and they both involve limestone—I’m reminded of the Crazannes Quarries project by Bernard Lassus, for which cuts, sections, “artificial rock formations,” shaped cliffs, and other designed geologies were introduced into and through the side of a French road. In effect, Lassus milled a new, powder-white landscape from the limestone.

But the ITER project seems to take the ambitions of Crazannes and turn them up to a nearly overwhelming degree: using a (to be clear, all but unrelated) landscape design process to produce moments of stellar combustion on the earth. It’s like an undeclared monument to Giordano Bruno—or, for that matter, to Aleister Crowley. A quarry in which we’ll build stars.

In any case, nestled there in its semi-subterranean, mine-like site and buzzing inside with radiation-resistant robot elevators, each “about the size of a large bus,” the ITER will recreate, again and again, “the process that powers the sun and most other stars. At extremely high temperatures, hydrogen nuclei will fuse to form helium, spitting out more energy than the process consumes, something that has never yet been achieved by a human-made device.”

[Image: A blanket of rebar is installed inside the pit at the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor; ©ITER Organization].

[Image: A blanket of rebar is installed inside the pit at the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor; ©ITER Organization].

The photos seen here—reproduced in accordance with ITER‘s image-use policy—shows the site work in action: quarrying, gridding, pouring, smoothing, and stabilizing, in preparation for the birth of new heavens.

[Images: Building the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor; ©ITER Organization].

[Images: Building the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor; ©ITER Organization].

More images are available at the ITER website.

[Image:

[Image:  [Image: The cotton mill].

[Image: The cotton mill].

[Image: Photos from

[Image: Photos from  [Image:

[Image:  [Image:

[Image:

[Image: The plug, courtesy of Homeland Security’s

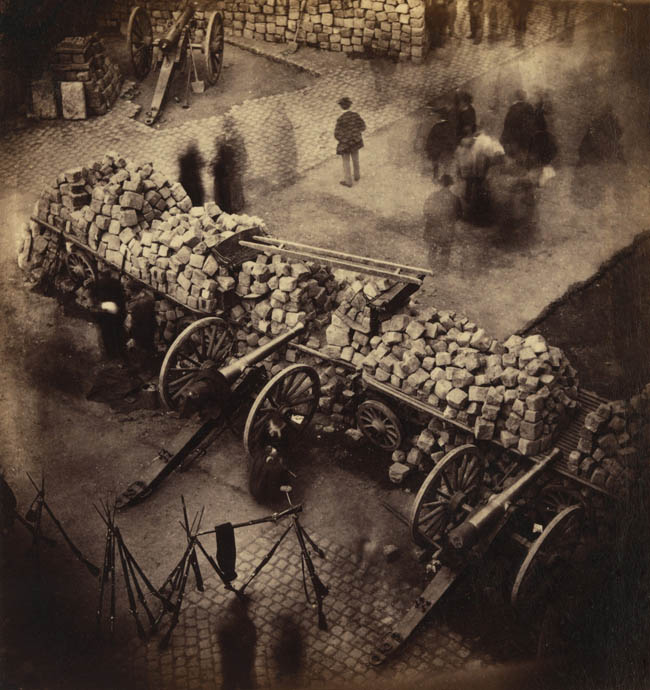

[Image: The plug, courtesy of Homeland Security’s  [Image: Paris barricade made from cobblestones (1871), photographed by Pierre-Ambrose Richebourg, via

[Image: Paris barricade made from cobblestones (1871), photographed by Pierre-Ambrose Richebourg, via

[Image: Photo by M. Scott Brauer, via

[Image: Photo by M. Scott Brauer, via  [Image: Kaleidoscope Ridge, Arizona (1982), photo by James Blair, courtesy of

[Image: Kaleidoscope Ridge, Arizona (1982), photo by James Blair, courtesy of

[Image: “Caves for New York” (1942) by Hugh Ferriss].

[Image: “Caves for New York” (1942) by Hugh Ferriss]. [Image: The

[Image: The

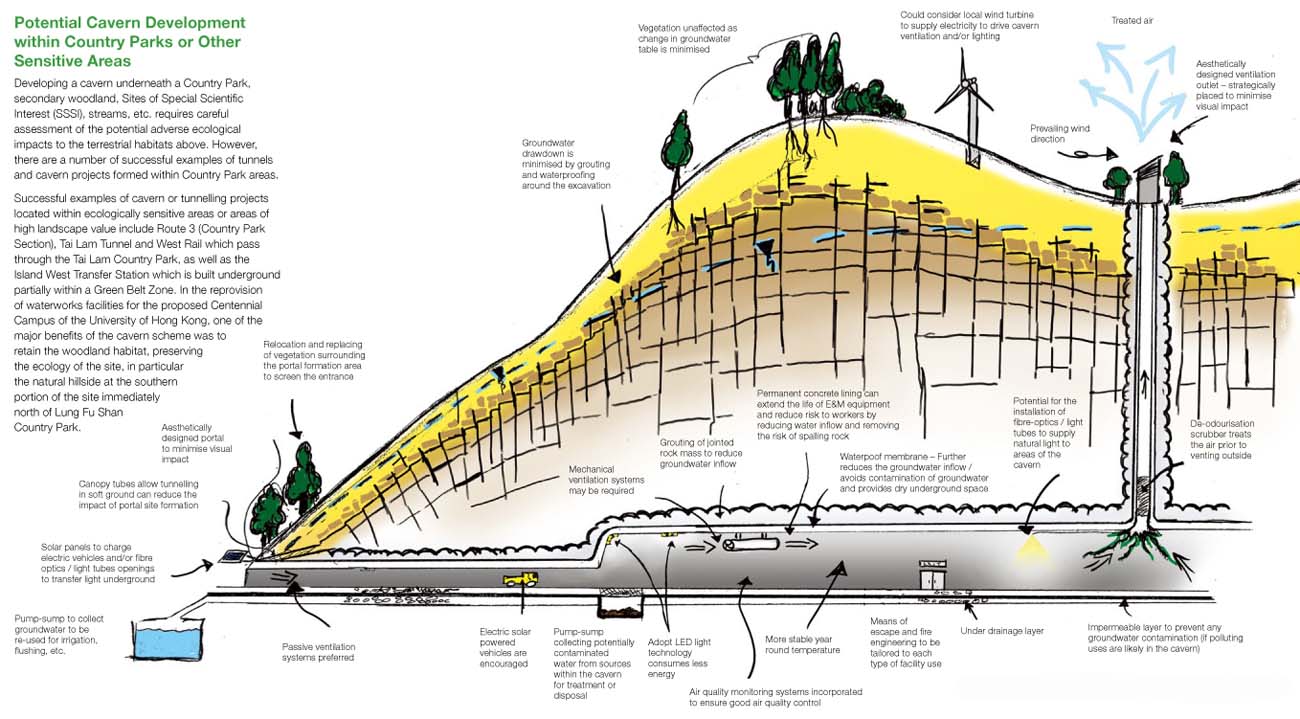

[Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the  [Images: From the

[Images: From the  [Image: From the

[Image: From the

[Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: The

[Image: The

[Images: The

[Images: The

[Images: The

[Images: The

[Image: Composite photograph by

[Image: Composite photograph by  [Image: Composite photograph by

[Image: Composite photograph by

[Images: Composite photographs by

[Images: Composite photographs by

[Image: The Chand Baori stepwell, courtesy of

[Image: The Chand Baori stepwell, courtesy of