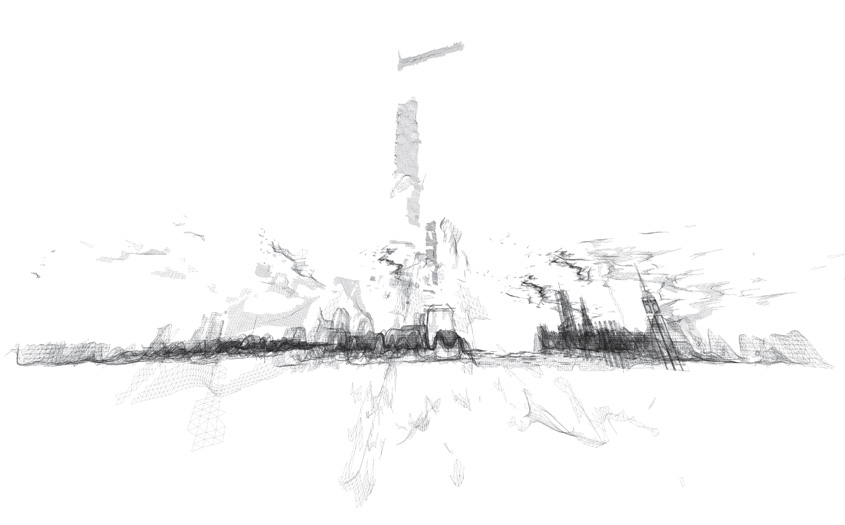

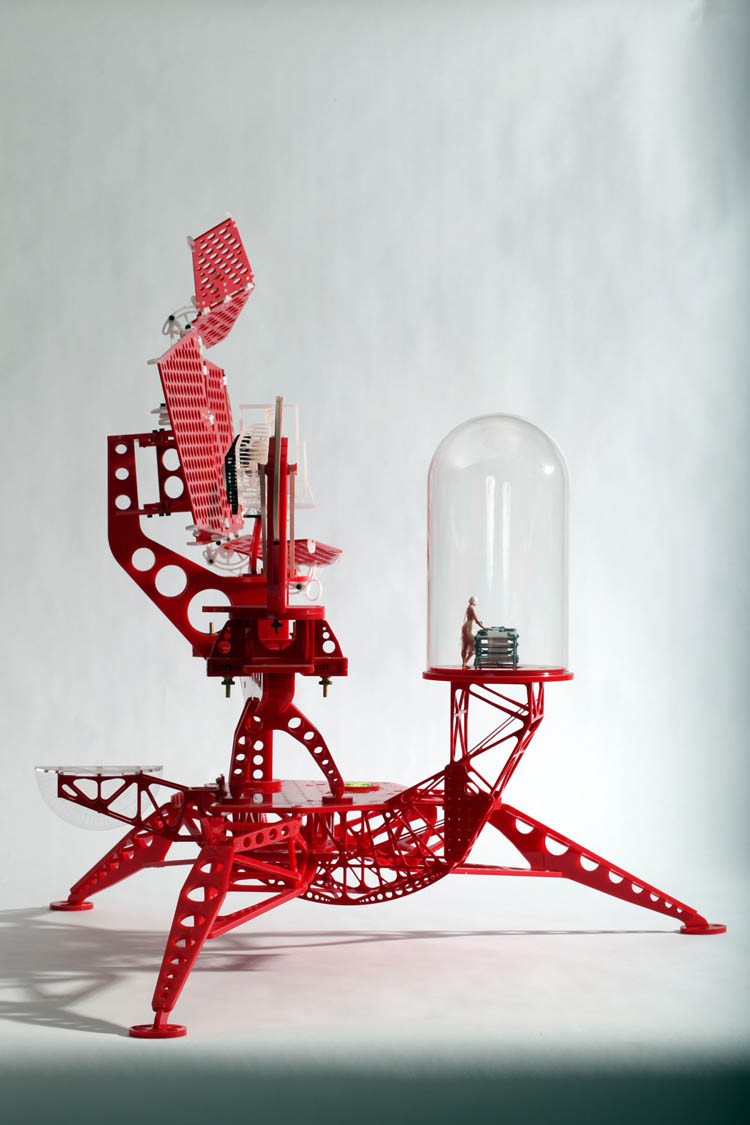

[Image: From Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism by Lateral Office/InfraNet Lab].

[Image: From Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism by Lateral Office/InfraNet Lab].

Going all the way back to the fall of 1997, my own interest in architecture was more or less reinvigorated—leading, by way of a long chain of future events, to the eventual start of BLDGBLOG—by Mary-Ann Ray’s installment in the great Pamphlet Architecture series, Seven Partly Underground Rooms and Buildings for Water, Ice, and Midgets.

To this day, the pamphlet format—short books, easily carried around town, packed with spatial ideas and constructive speculations—remains inspiring.

The 30th installment in this canonical series is thankfully a great one, authored by Lateral Office and InfraNet Lab, a design firm and its attendant research blog that I’ve been following for many years.

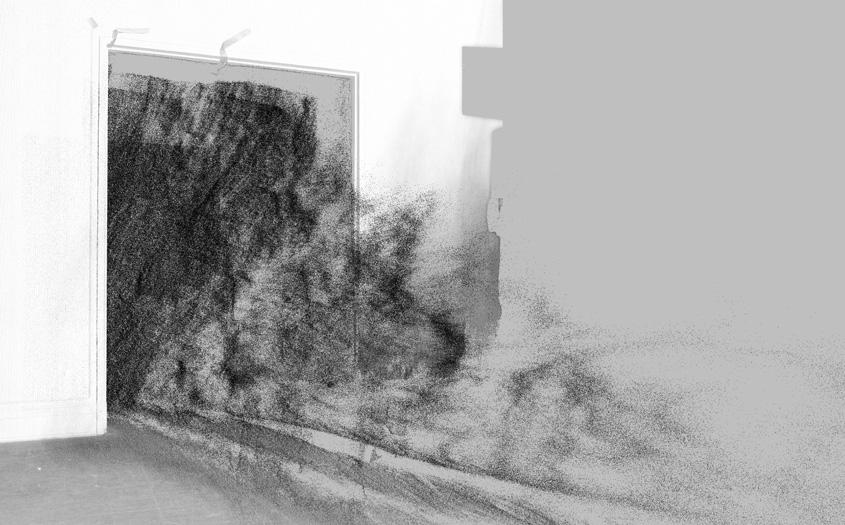

[Image: From Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism by Lateral Office/InfraNet Lab].

[Image: From Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism by Lateral Office/InfraNet Lab].

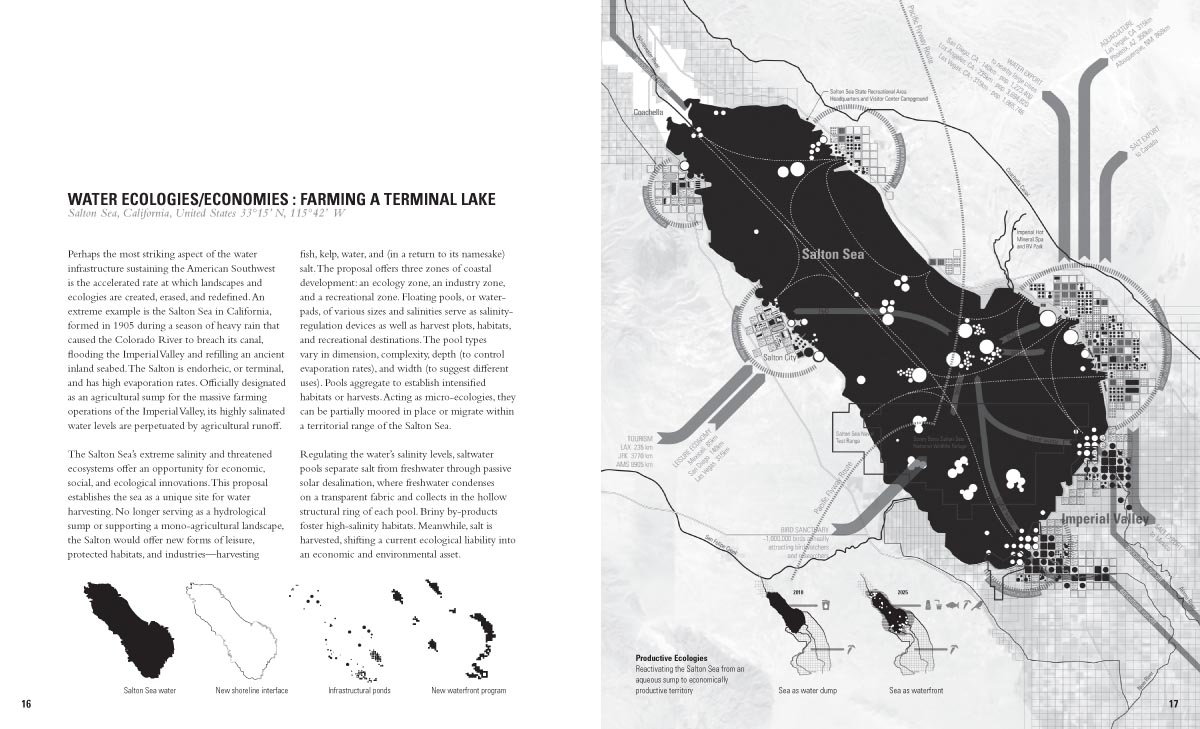

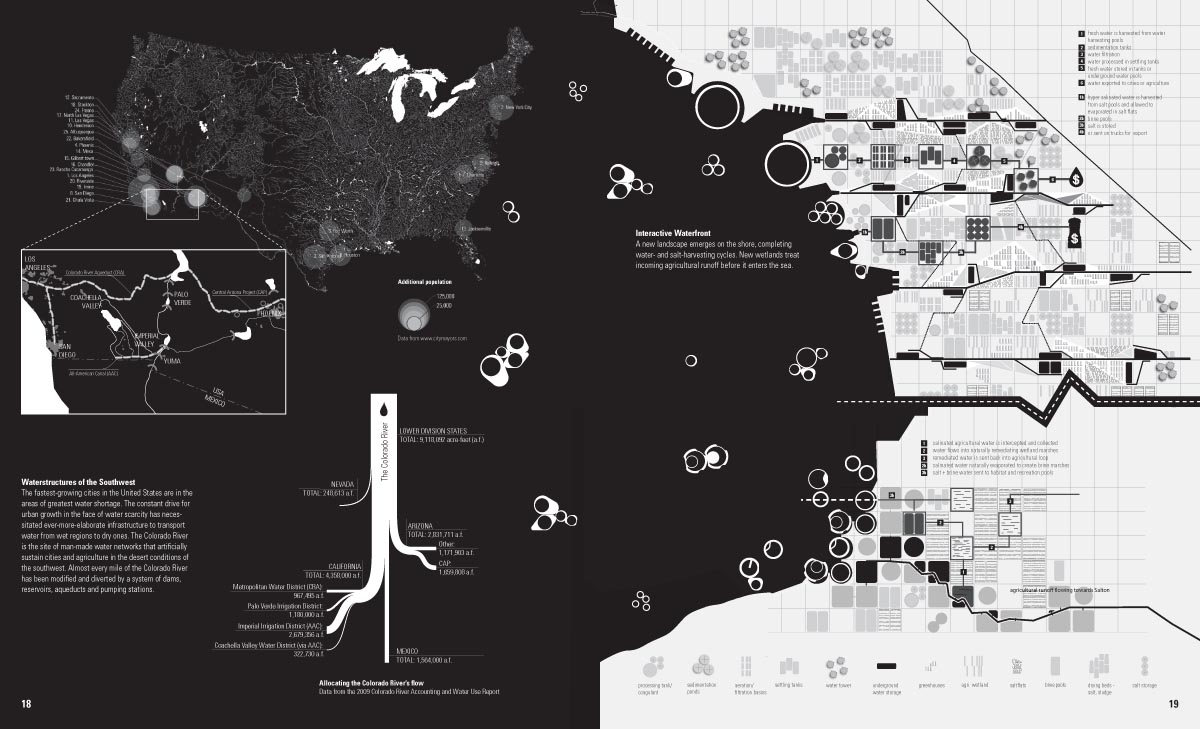

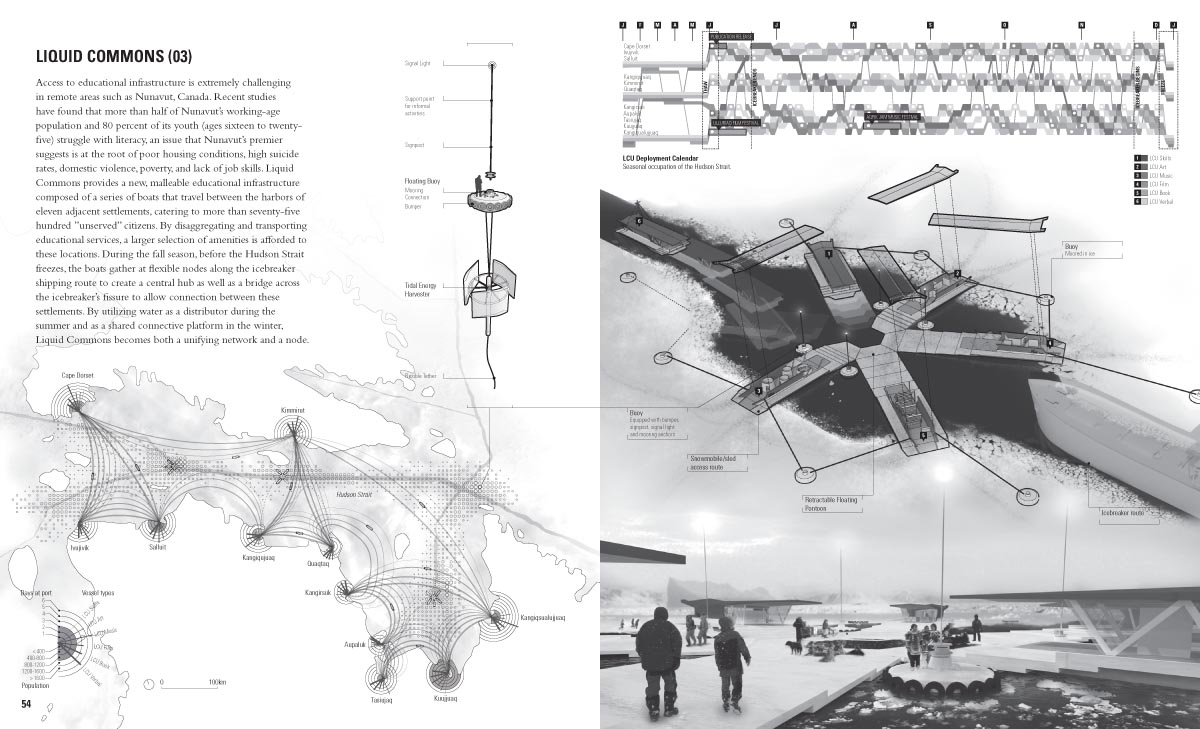

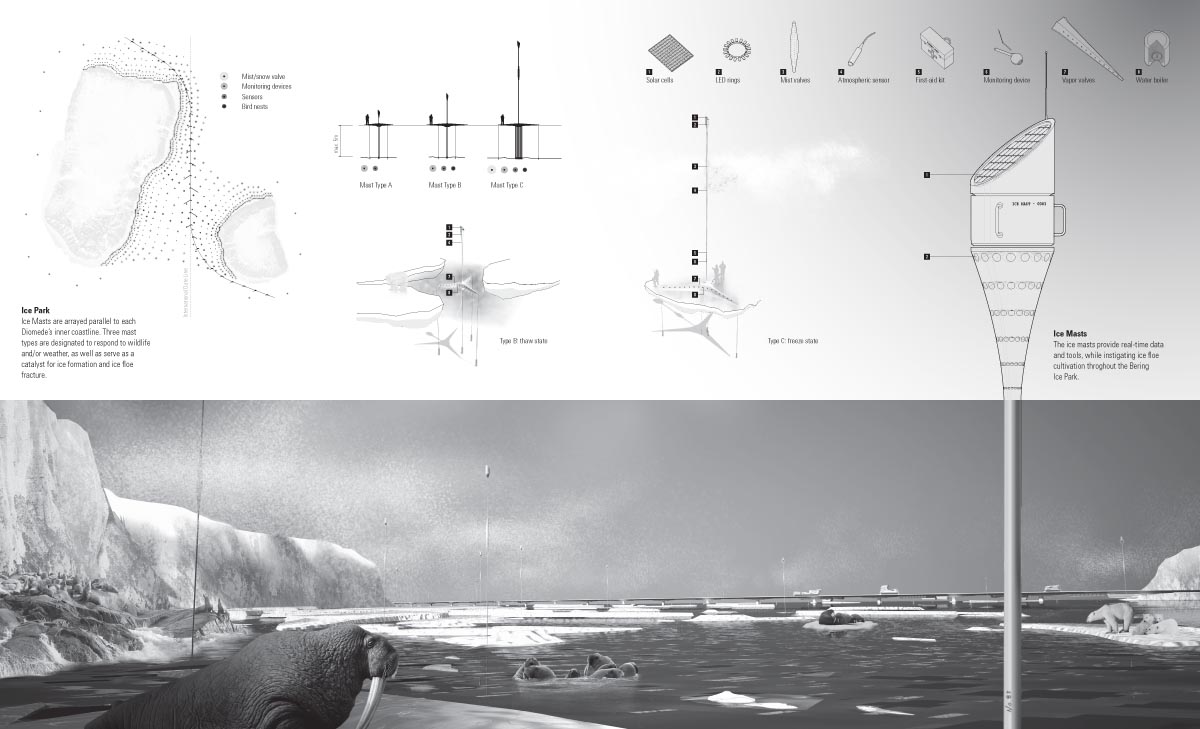

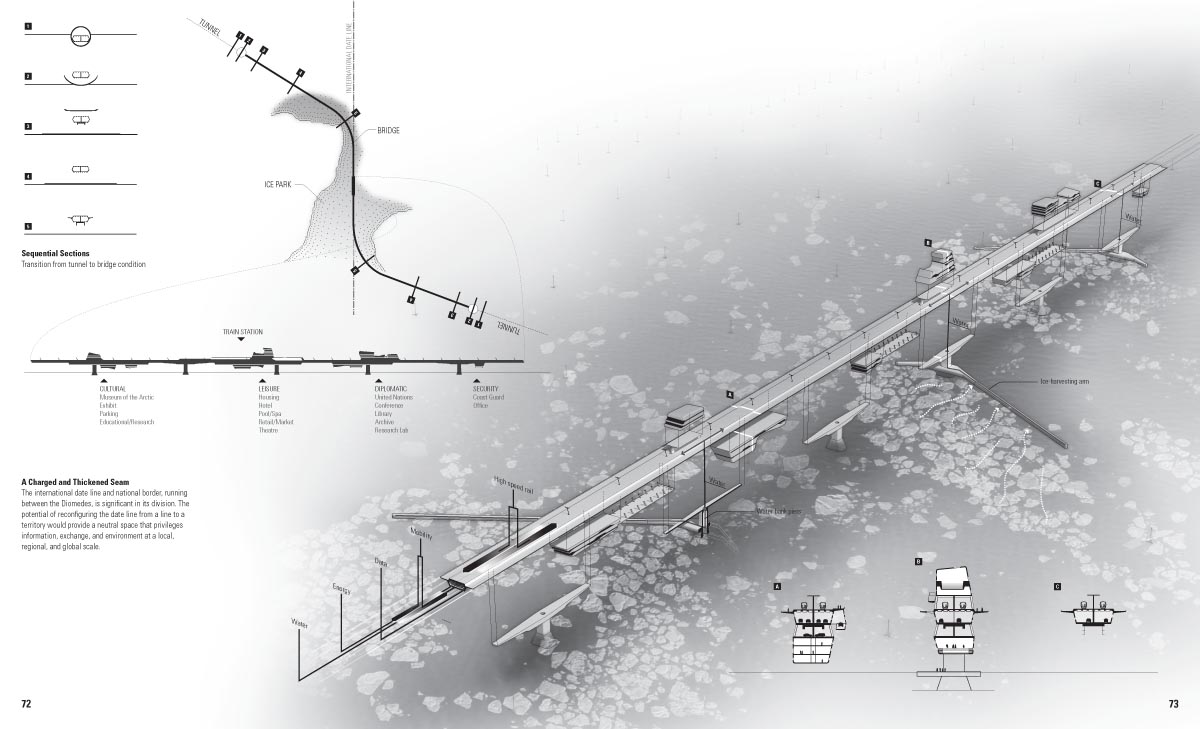

The premise of the work documented by their book, Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism, is to seek out moments in which architecturally dormant landscapes, from the Arctic Circle to the Salton Sea, can be activated by infrastructure and/or spatially reused. Their work is thus “opportunistic,” as the pamphlet’s title implies. It is architecture at the scale of infrastructure, and infrastructure at the scale of hemispheres and ecosystems—the becoming-continental of the architecture brief.

In the process, their proposed interventions are meant to augment processes already active in the terrain in question—processes that remain underutilized or, rather, below the threshold of spatial detection.

As the authors themselves describe it, these projects “double as landscape life support, creating new sites for production and recreation. The ambition is to supplement ecologies at risk rather than overhaul them.”

[Images: From Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism by Lateral Office/InfraNet Lab].

[Images: From Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism by Lateral Office/InfraNet Lab].

One of the highlights of the book for me is a section on the so-called “Next North.” Here, they offer “a series of proposals centered on the ecological and social empowerment of Canada’s unique Far North and its attendant networks.”

Throughout the twentieth century, the Canadian North had a sordid and unfortunate history of colonial enterprises, political maneuverings, and non-integrated development proposals that perpetuated sovereign control and economic development. Northern developments are intimately tied to the construction of infrastructure, though these projects are rarely conceived with a long-term, holistic vision. How might future infrastructures participate in cultivating and perpetuating ecosystems and local cultures, rather than threatening them? How might Arctic settlements respond more directly to the exigencies of this transforming climate and geography, and its ever-increasing pressures from the South? What is next for the North?

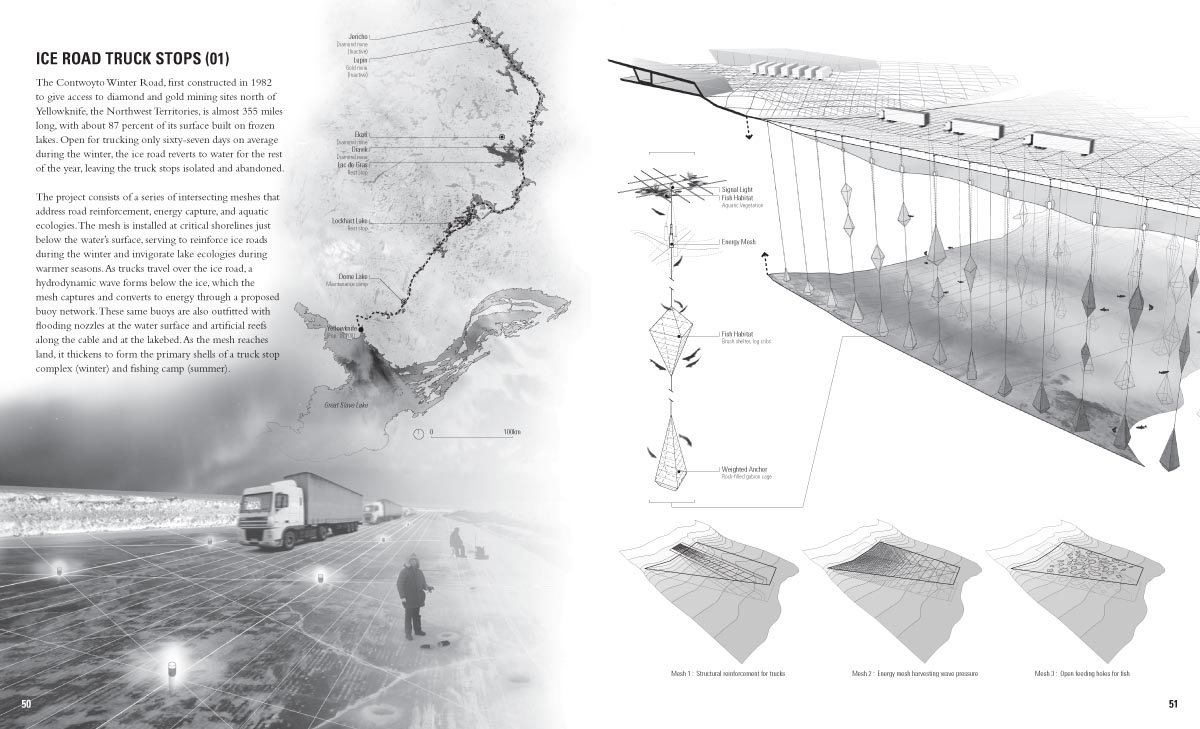

Three specific projects follow. One outlines the technical possibility of building “Ice Road Truck Stops.” These would use “intersecting meshes,” almost as a kind of cryotechnical rebar, inserted into the frozen surfaces of Arctic lakes to “address road reinforcement, energy capture, and aquatic ecologies.”

The mesh is installed at critical shorelines just below the water’s surface, serving to reinforce ice roads during the winter and invigorate lake ecologies during warmer seasons. As trucks travel over the ice road, a hydrodynamic wave forms below the ice, which the mesh captures and converts to energy through a proposed buoy network.

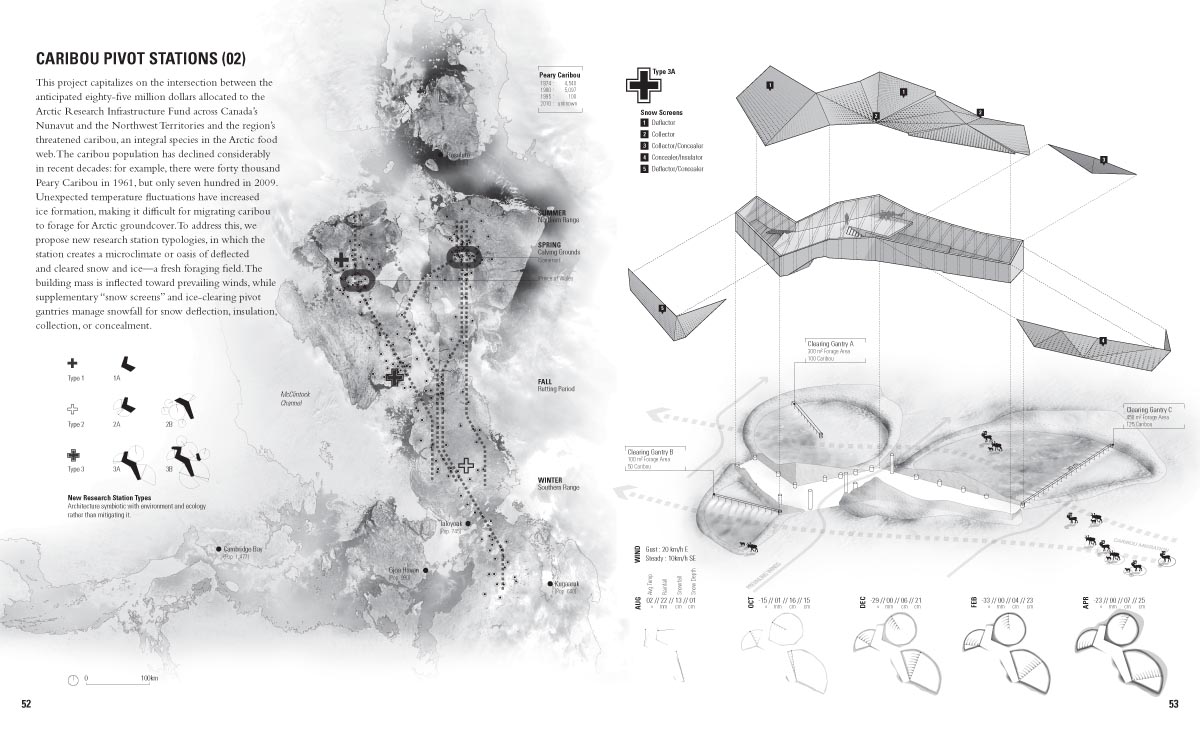

There is then a series of “Caribou Pivot Stations”—further proof that cross-species design is gathering strength in today’s zeitgeist—helping caribou to forage for food on their seasonal migrations; and a so-called “Liquid Commons,” which is a “malleable educational infrastructure composed of a series of boats that travel between the harbors of eleven adjacent communities.” It is a mobile, nomadic network bringing tax-funded educational opportunities to the residents of this emerging Next North.

[Images: From Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism by Lateral Office/InfraNet Lab].

[Images: From Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism by Lateral Office/InfraNet Lab].

Here, I should point out that the book has an air of earnestness—everything is very serious and technical and not to be laughed at—but the projects themselves often belie this attitude. It’s as if the authors are aware of, and even revel in, the speculative nature of their ideas, but seem somehow rhetorically unwilling to give away the game. But the implication that these projects are eminently buildable—shovel-ready projects just waiting for a financial green light to do things like “cultivate” ice in the Bering Strait (duly illustrated with a Photoshopped walrus) or “harvest” water from the Salton Sea—is a large part of what makes the book such an enjoyable read.

After all, does presenting speculative work as if it could happen tomorrow—as if it is anything but speculative—increase its architectural value? Or should such work always hold itself at an arm’s length from realizability, so as to highlight its provocative or polemical tone?

The projects featured in Coupling have an almost tongue-in-cheek buildability to them—such as recreational climbing walls on abandoned oil platforms in the Caspian Sea. This opens a whole slew of important questions about what rhetorical mode—what strategy of self-presentation—is most useful and appropriate for upstart architectural firms. (At the very least, this would make for a fascinating future discussion).

[Image: From Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism by Lateral Office/InfraNet Lab].

[Image: From Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism by Lateral Office/InfraNet Lab].

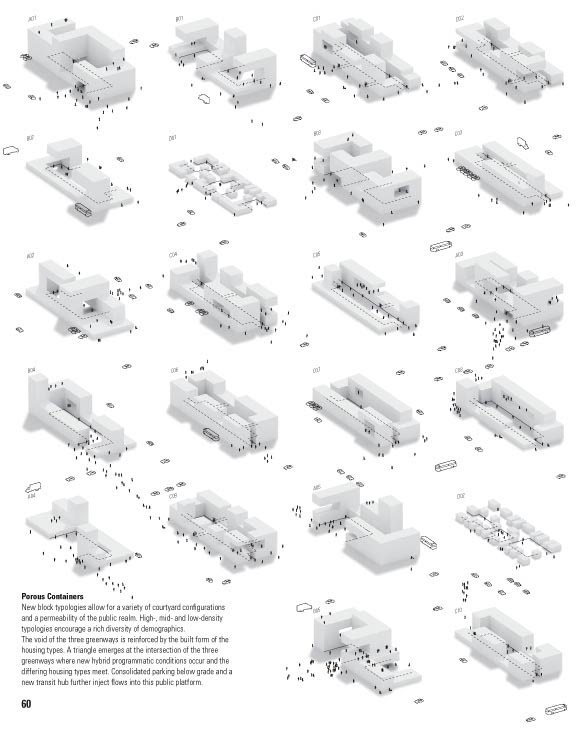

In any case, the book is loaded with diagrams, as you can see from the selections reproduced here, including a volumetric study (above) that runs through various courtyard typologies for a hypothetical mixed-use project in Iceland. For more on that particular work, see this older, heavily-illustrated BLDGBLOG post.

[Images: From Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism by Lateral Office/InfraNet Lab].

[Images: From Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism by Lateral Office/InfraNet Lab].

Essays by David Gissen, Keller Easterling, Charles Waldheim, and Christopher Hight round out the book’s content. It’s a solid pamphlet, both practical and imaginative—made even more provocative by its implied feasibility—and a fantastic choice for the 30th edition of this long-running series.

The London-based architectural group

The London-based architectural group  [Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Images: From

[Images: From

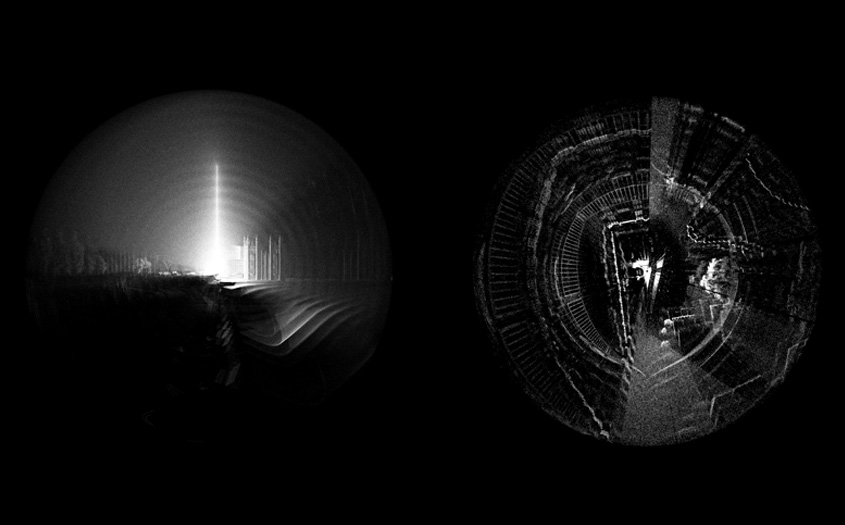

[Images: A hypothetical “stealth object,” resistant to laser-scanning, by ScanLAB].

[Images: A hypothetical “stealth object,” resistant to laser-scanning, by ScanLAB].

[Image: Photo by

[Image: Photo by

[Image: A bird in Rome].

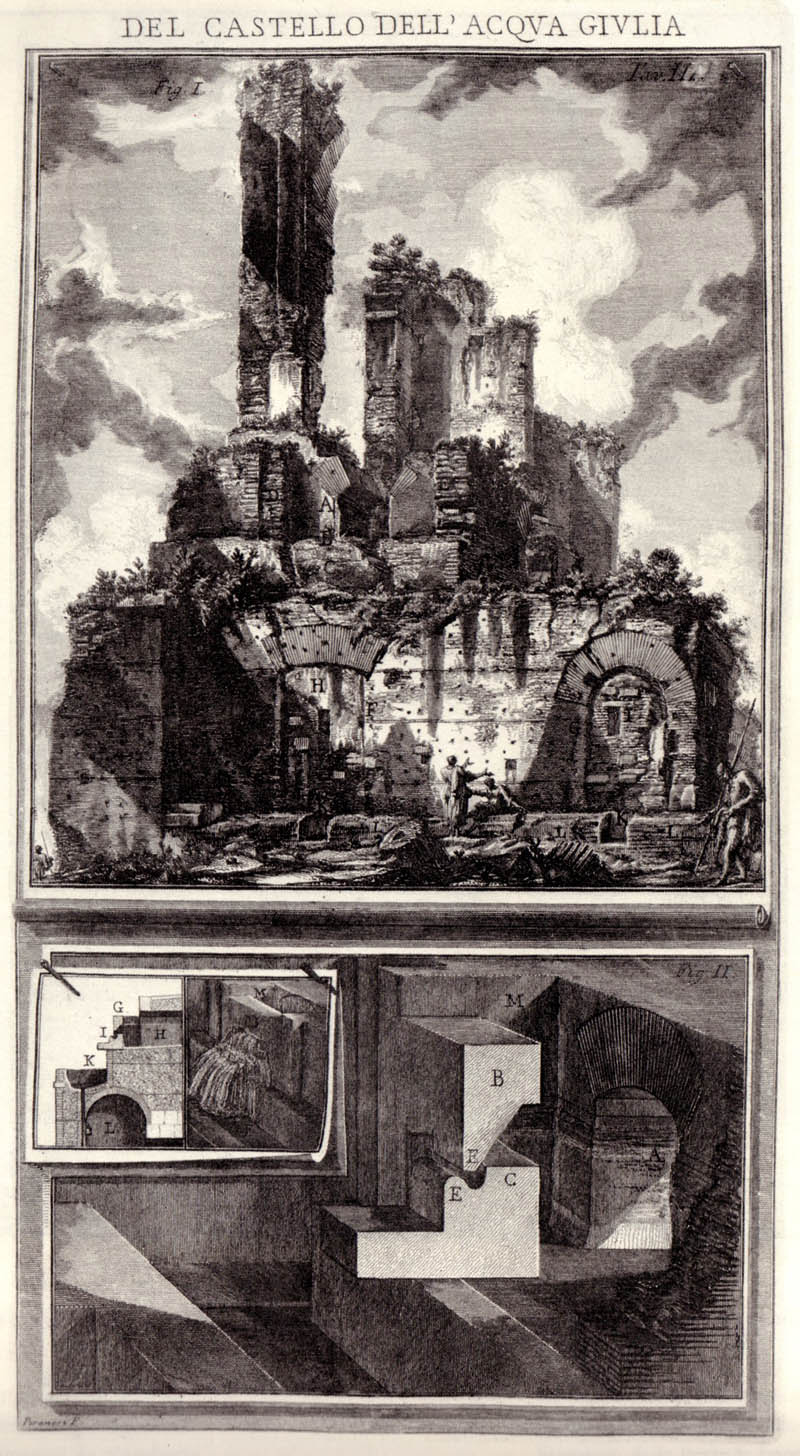

[Image: A bird in Rome]. [Image: Del Castello dell’Acqua Giulia by Piranesi].

[Image: Del Castello dell’Acqua Giulia by Piranesi].

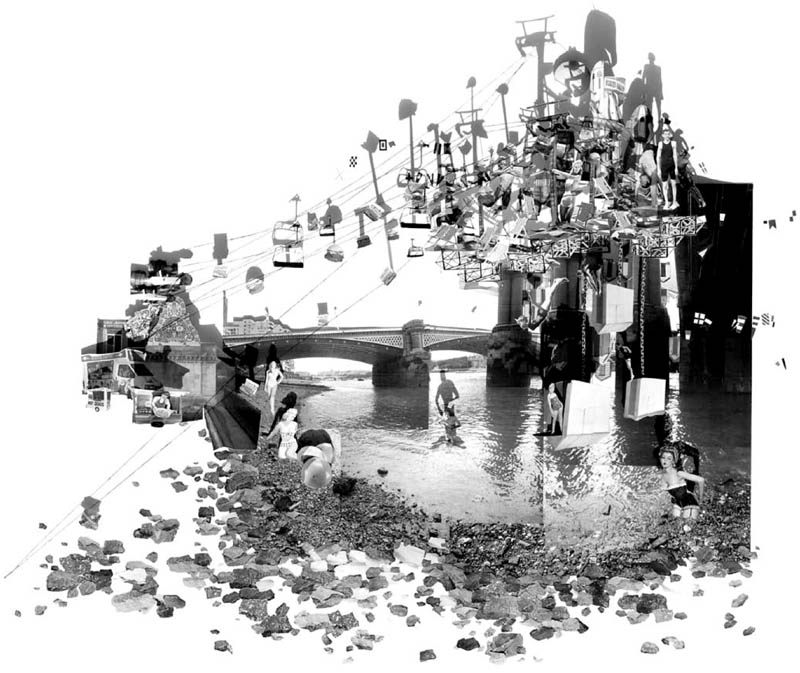

[Images: From “Dream Isle” by CJ Lim/Studio 8 Architects with

[Images: From “Dream Isle” by CJ Lim/Studio 8 Architects with  [Image: From “Carousel” by CJ Lim/Studio 8 Architects with Maxwell Mutanda, from

[Image: From “Carousel” by CJ Lim/Studio 8 Architects with Maxwell Mutanda, from

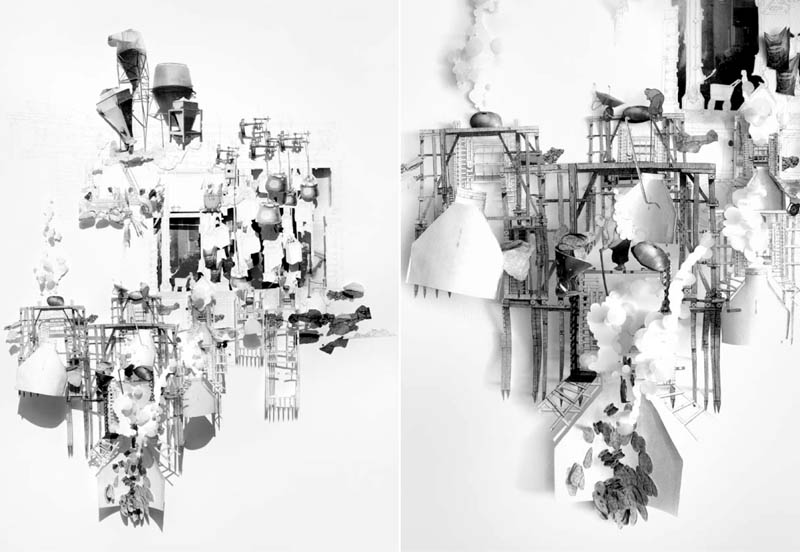

[Images: From “Discontinuous Cities” by CJ Lim/Studio 8 Architects with Maxwell Mutanda and Tomasz Marchewka, from

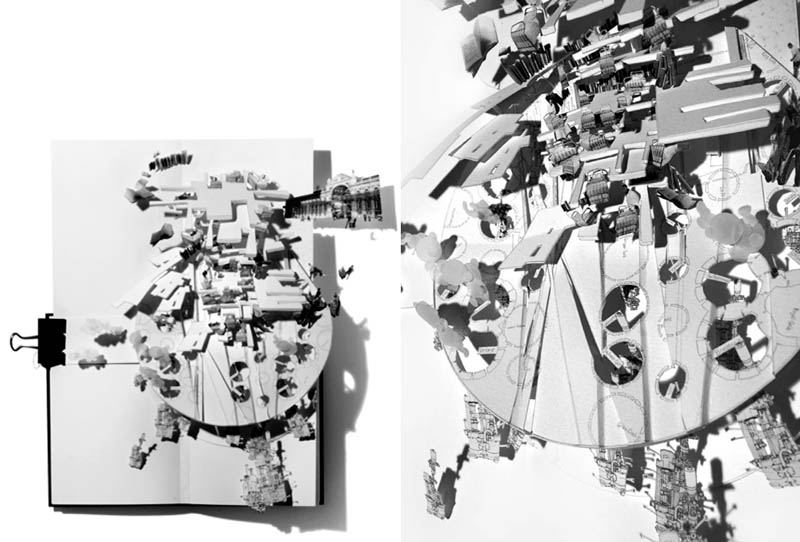

[Images: From “Discontinuous Cities” by CJ Lim/Studio 8 Architects with Maxwell Mutanda and Tomasz Marchewka, from  [Images: From “The Baker’s Garden” by CJ Lim/Studio 8 Architects with Safia Qureshi, from

[Images: From “The Baker’s Garden” by CJ Lim/Studio 8 Architects with Safia Qureshi, from  [Images: From “The Nocturnal Tower” by CJ Lim/Studio 8 Architects with Barry Cho, from

[Images: From “The Nocturnal Tower” by CJ Lim/Studio 8 Architects with Barry Cho, from  [Images: From “The Celestial River” by CJ Lim/Studio 8 Architects with Maxwell Mutanda and Sarah Custance, from

[Images: From “The Celestial River” by CJ Lim/Studio 8 Architects with Maxwell Mutanda and Sarah Custance, from

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: From the “

[Image: From the “

[Images: From the “

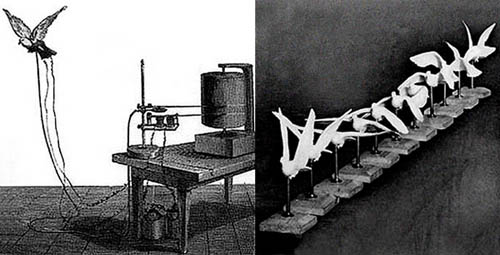

[Images: From the “ [Image: A chronophotograph by

[Image: A chronophotograph by

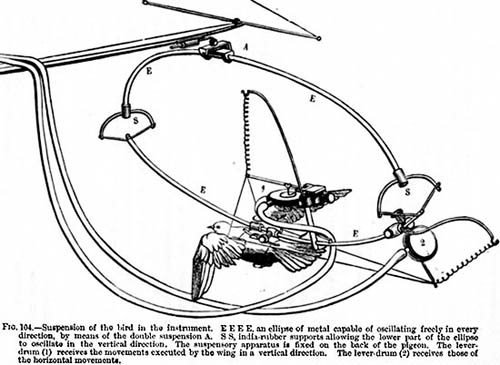

[Image: The spatial apparatus behind bird chronophotography].

[Image: The spatial apparatus behind bird chronophotography]. [Images: From the “

[Images: From the “ [Image: From the “

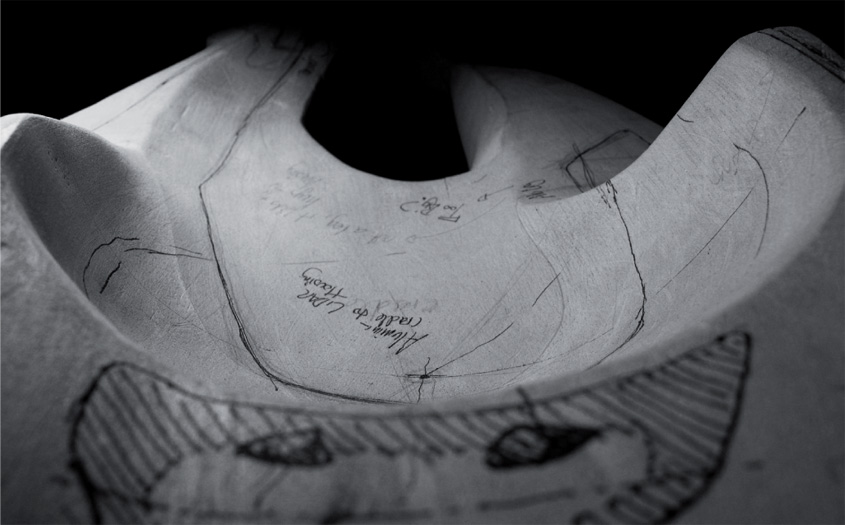

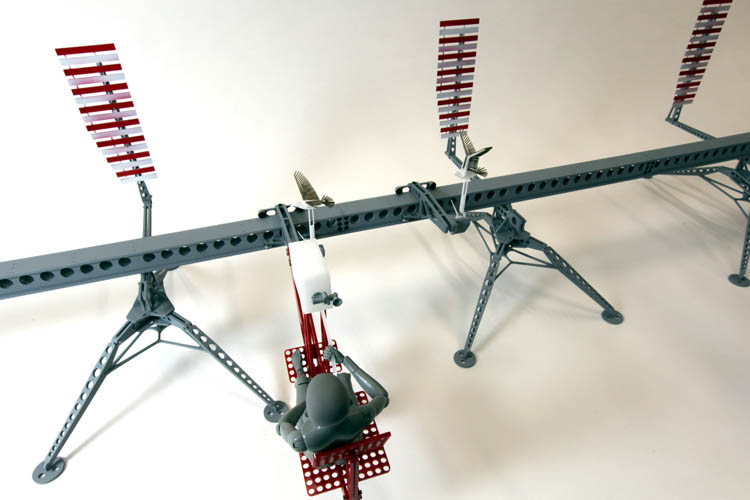

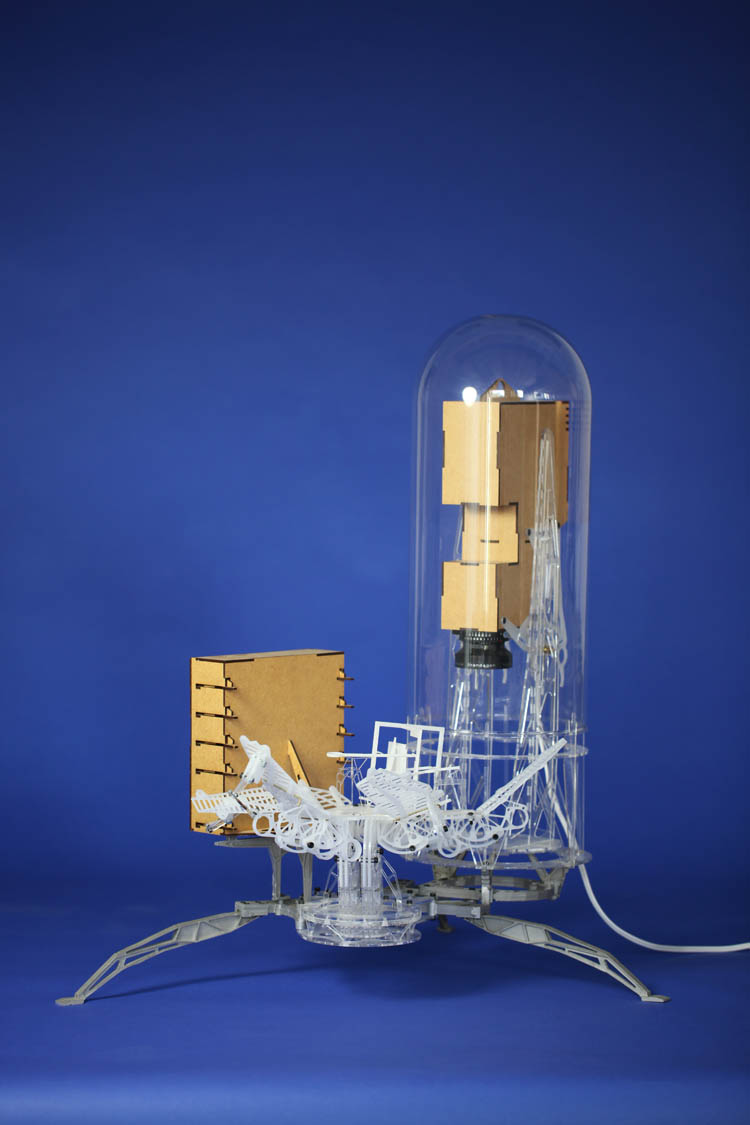

[Image: From the “ [Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by  [Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by  [Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Image: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Images: From a series of spatial drawing instruments by

[Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Images: From

[Images: From  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: An abandoned golf course leaves traces in the landscape in northern Los Angeles].

[Image: An abandoned golf course leaves traces in the landscape in northern Los Angeles]. [Image: The system goes from suck to blow; images courtesy of

[Image: The system goes from suck to blow; images courtesy of  [Image: A path originally meant to follow a now-abandoned golf course in northern Los Angeles].

[Image: A path originally meant to follow a now-abandoned golf course in northern Los Angeles].

[Image: The “

[Image: The “ [Image: The “

[Image: The “ [Image: The “

[Image: The “ [Image: The “

[Image: The “ But there are many ways in which the

But there are many ways in which the

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: The “

[Images: From “

[Images: From “

[Images: From a design for a zoo in St. Petersburg, Russia, by

[Images: From a design for a zoo in St. Petersburg, Russia, by  [Image: An archipelagic zoological park in St. Petersburg by

[Image: An archipelagic zoological park in St. Petersburg by

[Images: A future zoo in St. Petersburg by

[Images: A future zoo in St. Petersburg by  In any case, there are so many directions to go with this discussion of “animal architecture”—theoretical, practical, speculative, critical, and otherwise—that I can’t wait to see what sort of things are submitted to the Animal Architecture project. Register by 15 May 2011 to submit your own essays and designs.

In any case, there are so many directions to go with this discussion of “animal architecture”—theoretical, practical, speculative, critical, and otherwise—that I can’t wait to see what sort of things are submitted to the Animal Architecture project. Register by 15 May 2011 to submit your own essays and designs.