[Image: A glimpse of Honda’s brain-interface technology].

[Image: A glimpse of Honda’s brain-interface technology].

I thought I’d jump into the ongoing conversation swirling around Tim Maly’s Cyborg Month—of which you can read more here—with some loose thoughts about what an architectural cyborg might be.

There have already been some significant stabs made in this direction over the past few weeks, including a brief look at “architecture machines”—that is, “evolving systems that worked in ‘symbiosis’ with designer and resident,” promising to “turn the design process into a dialogue that would alter the traditional human-machine dynamic” and thus opening up the possibility of cyborg architecture.

But my interests here are both more speculative and more neurological—specifically, looking at the wiring together of buildings and nervous systems, and the strange possibilities that might result. As such, I’ll be revisiting/rewriting some older posts here, tailoring them specifically for the context of Maly’s Cyborg Month.

[Image: Earthly extensions crawl on Mars; courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech].

[Image: Earthly extensions crawl on Mars; courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech].

1) A few years ago, two unrelated bits of news accidentally merged for me, their headlines crossing to surreal effect. First, we learned that monkeys were able to move a robotic arm “merely by thinking.” The arm, which included “working shoulder and elbow joints and a clawlike ‘hand’,” was controllable after “probes the width of a human hair were inserted into the neuronal pathways of the monkeys’ motor cortex.” This field of research is referred to as “mind-controlled robotic prosthetics”—but the mind in control here is not human.

Second, the New York Times reported that “NASA’s Phoenix Mars lander has successfully lifted its robotic arm” up there on the surface of another planet. “Testing the arm will take a few days,” we read, “and the first scoops of Martian soil are to be dug up next week.”

And while I know that these stories are in no way connected, putting them together is like something from the pages of Mike Mignola: monkeys locked in a room somewhere, controlling the arms of machines on other planets.

As if we might discover, at the end of the day, that NASA wasn’t a human organization at all—it was a bunch of rhesus monkeys locked in a lab somewhere, enthroned amidst wires and brain-caps, like some new sign of the Tarot, lost in private visions of machines on alien worlds. An experiment gone awry.

Their “dreams” at night are actually video feeds from probes moving through outer darkness.

[Image: A “Demon” unmanned aerial drone by BAE Systems, courtesy of Popular Science].

[Image: A “Demon” unmanned aerial drone by BAE Systems, courtesy of Popular Science].

2) Among many other things in P.W. Singer’s highly recommended book Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the Twenty-First Century is a brief comment about military research into the treatment of paralysis.

In a subsection called “All Jacked Up,” Singer refers to “a young man from South Weymouth, Massachusetts,” who was “paralyzed from the neck down in 2001.” After nearly giving up hope for recovery, “a computer chip was implanted into his head.”

The goal was to isolate the signals leaving [his] brain whenever he thought about moving his arms or legs, even if the pathways to those limbs were now broken. The hope was that [his] intent to move could be enough; his brain’s signals could be captured and translated into a computer’s software code.

The man’s doctors thus hook him up to a computer mouse and then to a TV remote control, and the wounded man was soon able not only to surf the web but to watch HBO.

What I can’t stop thinking about, however, is where this research “opens up some wild new possibilities for war,” as Singer writes.

In other words, the military has asked, why hook this guy up to a remote control TV when you could hook him up to an armed drone aircraft flying somewhere above Afghanistan? The soldier could simply pilot the plane with his thoughts.

This vision—of paralyzed soldiers thinking unmanned planes through distant theaters of war—is both terrible and stunning.

Singer goes on to describe DARPA‘s “Brain-Interface Project,” which hoped to teach paralyzed patients how to control machines via thought—and to do so in the service of the U.S. military.

Later in the book, Singer describes research into advanced, often robotic prostheses; “these devices are also being wired directly into the patient’s nerves,” he writes.

This allows the solder to control their artificial limbs via thought as well as have signals wired back into their peripheral nervous system. Their limbs might be robotic, but they can “feel” a temperature change or vibration.

When this is put into the context of the rest of Singer’s book—where we read, for instance, that “at least 45 percent of [the U.S. Air Force’s] future large bomber fleet [will be] able to operate without humans aboard,” with other “long-endurance” military drones soon “able to stay aloft for as long as five years,” and if you consider that, as Singer writes, the Los Angeles Police Department “is already planning to use drones that would circle over certain high-crime neighborhoods, recording all that happens”—you get into some very heady terrain, indeed. After all, the idea that those drone aircraft circling over Los Angeles in the year 2015 are actually someone’s else literal daydream both terrifies and blows me away.

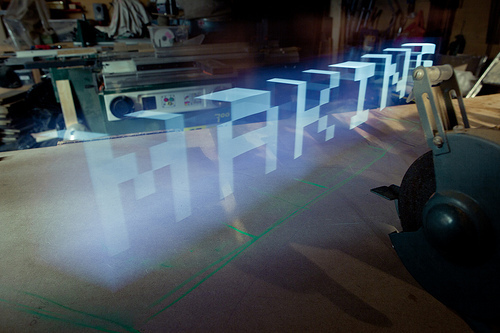

On the other hand, if you can directly link the brain of a paralyzed soldier to a computer mouse—and then onward to a drone aircraft, and perhaps onward again to an entire fleet of armed drones circling over enemy territory—then surely you could also hook that brain up to, say, lawnmowers, remote-controlled tunneling machines, lunar landing modules, Mars rovers, strip-mining equipment, woodworking tools, and even 3D printers.

[Image: 3D printing, via Thinglab].

[Image: 3D printing, via Thinglab].

The idea of brain-controlled wireless digging machines, in particular, just astonishes me; at night you dream of tunnels—because you are actually in control of tunneling equipment as you sleep, operating somewhere beneath the surface of the planet.

A South African platinum mine begins to diverge wildly from known sites of mineral wealth, its excavations more and more abstract as time goes on—carving M.C. Escher-like knots and strange excursive whorls through ancient reefwork below ground—and it’s because the mining engineer, paralyzed in a car accident ten years ago and in control of the digging machines ever since, has become addicted to morphine.

Or perhaps this could even be used as a new and extremely avant-garde form of psychotherapy. For instance, a billionaire in Los Angeles hooks his depressed teenage son up to Herrenknecht tunneling equipment which has been shipped, at fantastic expense, to Antarctica. An unmappably complex labyrinth of subterranean voids is soon created; the boy literally acts out through tunnels. If rock is his paint, he is its Basquiat.

Instead of performing more traditional forms of Freudian analysis by interviewing the boy in person, a team of highly-specialized dream researchers is instead sent down into those artificial caverns, wearing North Face jackets and thick gloves, where they deduce human psychology from moments of curvature and angle of descent.

My dreams were a series of tunnels through Antarctica, the boy’s future headstone reads.

[Image: The hieroglyphic end of a Canadian potash mine; courtesy of AP/The Australian].

[Image: The hieroglyphic end of a Canadian potash mine; courtesy of AP/The Australian].

Returning to Singer, briefly, he writes that “Many robots are actually just vehicles that have been converted into unmanned systems”—so if we can robotize aircraft, digging machines, riding lawnmowers, and even heavy construction equipment, and if we can also directly interface the human brain to the controls of these now wireless robotic mechanisms, then the design possibilities seem limitless, surreal, and well worth exploring (albeit with great moral caution) in real life.

3) What, then, in this context, might an architectural cyborg be? While it’s tempting to outline a number of scenarios in which a human brain could be directly wired into, say, the elevator control room of a downtown high-rise, or into the traffic lights of a Chinese metropolis, this scenario could also be disturbingly reversed.

In other words, why have a building somehow controlled by a human brain, when a human brain could instead be controlled by a building?

Like something out of Michael Crichton’s Coma—or even the film Hannibal (NSFW and highly disturbing!)—future elevator banks in New York’s replacement World Trade Center cause wireless twitching in an otherwise bed-bound patient. That is, the patient moves because of the elevators, and not the other way around.

Imagine a zombie horror film, complete with stumbling hordes guided not by demonic hunger but by the malfunctioning HVAC system of a building outside town…

[Image: A circuit diagram].

[Image: A circuit diagram].

At this point, though, I’d rather step back from these morally uncomfortable images and suggest instead that buildings connected to other buildings might form their own ersatz neurology: like the hacked brain of a military paralytic, one building’s elevators would actually control the elevators in another building.

Networked examples of this are easy enough to invent: the computer system of one building is cross-wired into the circuitous guts of another structure, be it a skyscraper, an airplane, a geostationary satellite, a moving truck, or an interstellar probe built by NASA (and why stop at buildings—why not networked plants?). The changing speeds of a building’s escalators become more like graphs: responding to—and thus diagramming—signals from a rover on Mars.

They are pieces of equipment, we might say, neurologically interfering with one another.

In many ways, this just takes us back to the cybernetic designs mentioned earlier, but it also leads to a general question: are two buildings hooked up to each other, in the most intimate ways, their HVACs purring in perfect co-harmony, responding to and controlling one another, each incomplete without its cross-wired partner, actually cyborgs?

For more posts in Tim Maly’s ongoing series, check out 50 Posts About Cyborgs.

[Images: From Making Future Magic by BERG/Dentsu London, courtesy of BERG Studio].

[Images: From Making Future Magic by BERG/Dentsu London, courtesy of BERG Studio].  [Image: From Making Future Magic by BERG/Dentsu London, courtesy of BERG Studio].

[Image: From Making Future Magic by BERG/Dentsu London, courtesy of BERG Studio]. [Image: From Making Future Magic by BERG/Dentsu London, courtesy of BERG Studio].

[Image: From Making Future Magic by BERG/Dentsu London, courtesy of BERG Studio]. [Image: From Making Future Magic by BERG/Dentsu London, courtesy of BERG Studio].

[Image: From Making Future Magic by BERG/Dentsu London, courtesy of BERG Studio].

[Image: A parking spiral, originally published in

[Image: A parking spiral, originally published in  [Images: The micro-culture of the motorway; images courtesy Associated Press/

[Images: The micro-culture of the motorway; images courtesy Associated Press/ [Images: The traffic jam as scene from Dante; images courtesy Associated Press/

[Images: The traffic jam as scene from Dante; images courtesy Associated Press/ [Image: Courtesy of Newscom and the

[Image: Courtesy of Newscom and the  [Image: From

[Image: From

[Image: A glimpse of

[Image: A glimpse of  [Image: Earthly extensions crawl on Mars; courtesy of

[Image: Earthly extensions crawl on Mars; courtesy of  [Image: A “Demon” unmanned aerial drone by BAE Systems, courtesy of

[Image: A “Demon” unmanned aerial drone by BAE Systems, courtesy of  [Image: 3D printing, via

[Image: 3D printing, via  [Image: The hieroglyphic end of a Canadian potash mine; courtesy of AP/

[Image: The hieroglyphic end of a Canadian potash mine; courtesy of AP/ [Image: A circuit diagram].

[Image: A circuit diagram].

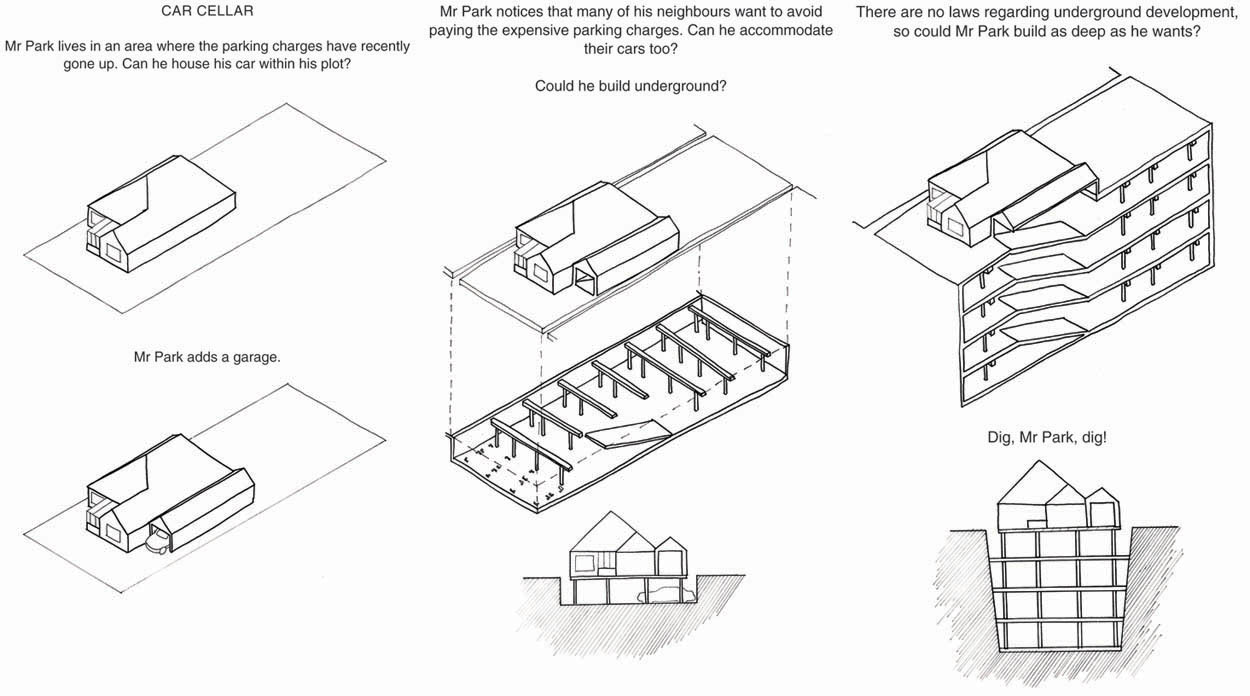

[Image: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Image: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams]. [Images: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams].

[Images: Courtesy of David Knight and Finn Williams]. [Image: An awesome glimpse of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of

[Image: An awesome glimpse of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of  [Images: Another mind-bending example of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of

[Images: Another mind-bending example of “the permission we already have,” courtesy of

[Image: A prison in the desert soutwest; photo by, and courtesy of,

[Image: A prison in the desert soutwest; photo by, and courtesy of,

[Images:

[Images:

[Image: “How to photograph an atomic bomb,” via the

[Image: “How to photograph an atomic bomb,” via the

[Image: The original graphic for

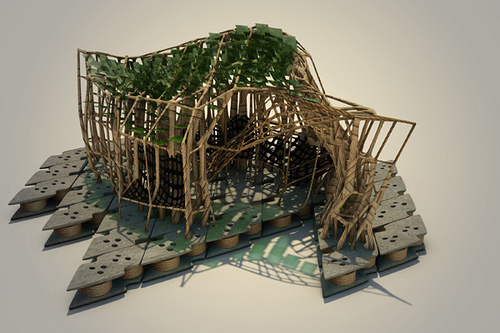

[Image: The original graphic for  [Image: P.YGROS.C—short for “Passive Hygroscopic Curls,” as if

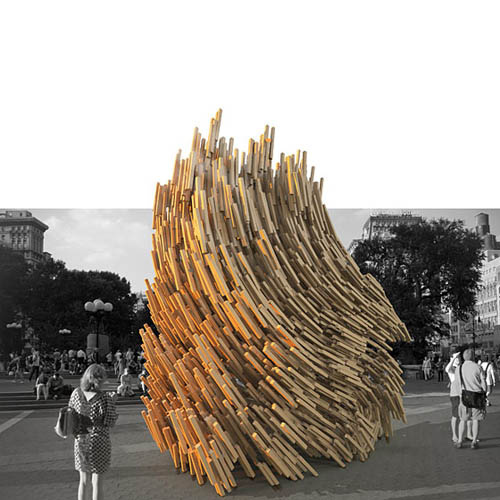

[Image: P.YGROS.C—short for “Passive Hygroscopic Curls,” as if  [Image: Gathering by Dale Suttle, So Sugita, and Ginna Nguyen of New York City].

[Image: Gathering by Dale Suttle, So Sugita, and Ginna Nguyen of New York City].

[Images: (top)

[Images: (top)  [Image: XNOT by Morgan Reynolds, Ravi Raj, and

[Image: XNOT by Morgan Reynolds, Ravi Raj, and

[Image: The

[Image: The  [Image: One of the originally commissioned vans].

[Image: One of the originally commissioned vans].

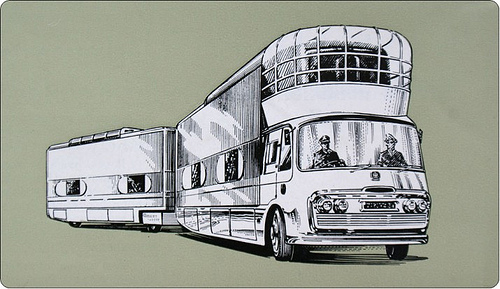

[Images: Mobile cinemas commissioned by the UK Ministry of Technology].

[Images: Mobile cinemas commissioned by the UK Ministry of Technology].

[Images: The

[Images: The  [Image: Inside the

[Image: Inside the

[Images: The van, awaiting renovation].

[Images: The van, awaiting renovation].

[Images: Vintage photos of the original cinema van series].

[Images: Vintage photos of the original cinema van series]. [Image: Graphics for the cinema van].

[Image: Graphics for the cinema van].

[Image:

[Image:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images:

[Images: