A few months after September 11th, the New York Times published a kind of geological look at the War on Terror.

In a short but amazingly interesting – albeit subscriber-only – article, the NYTimes explored how ancient landscape processes and tectonic events had formed the interconnected mountain caves in which Osama bin Laden was, at that time, hiding.

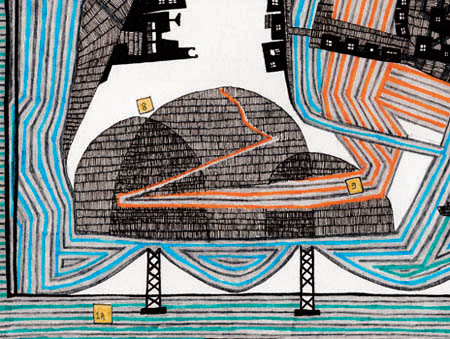

[Image: The topography of Afghanistan, a sign of deeper tectonics. In a cave somewhere amidst those fractal canyons sat Osama bin Laden, in the darkness, rubbing his grenades, complaining about women, Jews, and homosexuals…].

[Image: The topography of Afghanistan, a sign of deeper tectonics. In a cave somewhere amidst those fractal canyons sat Osama bin Laden, in the darkness, rubbing his grenades, complaining about women, Jews, and homosexuals…].

“The area that is now Afghanistan started to take shape hundreds of millions of years ago,” the article explains, “when gigantic rocks, propelled by the immense geological forces that continuously rearrange the earth’s landforms, slammed into the landmass that is now Asia.”

From here, rocks “deep inside the earth” were “heated to thousands of degrees and crushed under tremendous pressures”; this caused them to “flow like taffy.” And I love this next sentence: “Just like the air masses in thunderstorms, the warmer rocks rise and the cooler ones sink, setting up Ferris wheel-shaped circulations of magma that drag along the crust above them. Over time, these forces broke off several pieces off the southern supercontinent of Gondwanaland – the ancient conglomeration of South America and Africa – and carried them north toward Asia.”

Of course, Afghanistan – like most (but not all) of the earth’s surface – was once entirely underwater. There, beneath the warm waves of the Tethys Seaway, over millions of year, aquatic organisms “were compressed into limestone.”

Limestone, incidentally, is less a rock than a kind of strange anatomical by-product – something the living can become.

In any case, these massive and shuddering tectonic mutations continued:

Minerals from the ocean floor, melted by the heat of the interior, then flowed back up near the surface, forming rich deposits of copper and iron (minerals that could someday finance an economic boom in Afghanistan). The limestone along the coasts of Asia and India buckled upward, like two cars in a head-on collision. Water then ate away at the limestone to form the caves. Though arid today, Afghanistan was once warm and wet. Carbon dioxide from decaying plants dissolves into water to form carbonic acid, and in water-saturated underground areas, the acid hollowed out the limestone to form the caves, some several miles long.

The story gets really interesting here, then; think of it as the CIA-meets-geology.

[Image: Via the Telegraph].

[Image: Via the Telegraph].

What happened was that Osama bin Laden, in hiding after 9/11, started releasing his famous videotapes – but those tapes included glimpses of cave walls and rocky hillsides behind him.

When John F. Shroder – a geologist specializing in the structure of Himalayan Afghanistan – saw the tapes, he tried to interpret their setting and background, looking for mineralogical clues as to where bin Laden might be. Like a scene from The Conversation – or, hermeneutics gone geo-cinematic – Shroder pored over the tapes, fast-forwarding and rewinding, scanning for subtle signs…

It was the surface of the earth on TiVo.

“Afghanistan’s fighters find shelter in the natural caves,” the New York Times continues. “They also make their own, often in the mountains of crystalline rock made of minerals like quartz and feldspar, the pieces of Afghanistan that were carried in by plate tectonics. ‘This kind of rock is extremely resistant,’ Dr. Shroder said. ‘It’s a good place to build bunkers, and bin Laden knows that.’ Dr. Shroder said he believed that Mr. bin Laden’s video in October was taken in a region with crystalline rocks like those south of Jalalabad.”

All of which makes me think that soldiers heading off to Afghanistan could do worse than to carry bulletproof copies of Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth along with them.

As another New York Times article puts it: “Afghanistan is a virtual ant farm of thousands of caves, countless miles of tunnels, deeply dug-in bases and heavily fortified bunkers. They are the product of a confluence of ancient history, climate, geology, Mr. bin Laden’s own engineering background – and, 15 years back, a hefty dose of American money from the Central Intelligence Agency.”

Bin Laden et al could thus “take their most secret and dangerous operations to earth,” hidden beneath the veil of geology.

(Elsewhere: Bryan Finoki takes a tour of borders, tunnels, and other Orwellian wormholes; see also BLDGBLOG’s look at Terrestrial weaponization).

[Image: “Chat piles” looming round the “abandoned storefronts and empty lots” of Picher, OK; photo by Matt Wright, author of the article I’ve been quoting. See also this photo gallery from the US Geological Survey’s own tour of Picher, or this series of images from 1919].

[Image: “Chat piles” looming round the “abandoned storefronts and empty lots” of Picher, OK; photo by Matt Wright, author of the article I’ve been quoting. See also this photo gallery from the US Geological Survey’s own tour of Picher, or this series of images from 1919]. [Image: The “Voronoi Shelf” and “Extruded Chair” by Marc Newsom; image by Lamay Photo, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, NYC].

[Image: The “Voronoi Shelf” and “Extruded Chair” by Marc Newsom; image by Lamay Photo, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, NYC]. [Image: A “lathed marble table” by Marc Newsom; image by Lamay Photo, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, NYC].

[Image: A “lathed marble table” by Marc Newsom; image by Lamay Photo, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, NYC].

[Images: Two “extruded” tables by Marc Newsom; image by Lamay Photo, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, NYC].

[Images: Two “extruded” tables by Marc Newsom; image by Lamay Photo, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, NYC]. [Image: Tresor’s new home; photo by Thilo Rückeis for Der Tagesspiegel, via

[Image: Tresor’s new home; photo by Thilo Rückeis for Der Tagesspiegel, via

[Images: The staircase down, and the dancefloor it led to; photos courtesy of

[Images: The staircase down, and the dancefloor it led to; photos courtesy of  [Image: Humans beneath the surface of the earth, listening to music; photo courtesy of

[Image: Humans beneath the surface of the earth, listening to music; photo courtesy of  [Image: The topography of

[Image: The topography of  [Image: Via the

[Image: Via the  For some reason, BLDGBLOG’s recent look at

For some reason, BLDGBLOG’s recent look at  – along with

– along with  [Image: “A white drywall partition, in background at left, separates Simon Taub from Chana Taub in their Brooklyn home.” Via

[Image: “A white drywall partition, in background at left, separates Simon Taub from Chana Taub in their Brooklyn home.” Via  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Excerpt from

[Image: Excerpt from  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  [Image: Via

[Image: Via  Lawrence Weschler’s

Lawrence Weschler’s  [Image: A brief homage to

[Image: A brief homage to