“About 600 feet deep in the bedrock that supports Midtown Manhattan,” we meet “a 450-ton tunnel-boring machine known as the Mole.”

The Mole is “digging City Tunnel No. 3 far beneath Manhattan’s street level, part of a 50-year, $6 billion project to upgrade New York City’s water system.”

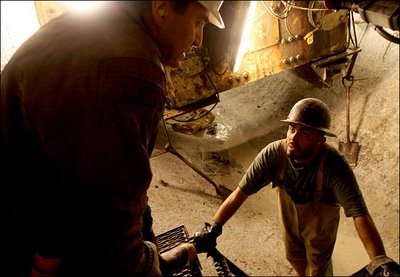

[Image: By Ozier Muhammad for The New York Times].

[Image: By Ozier Muhammad for The New York Times].

As the New York Times describes, this is actually the “second phase of City Tunnel No. 3, a 60-mile tunnel that began in the Bronx in 1970 and is scheduled for completion in 2020. By then, the tunnel will be able to handle the roughly one billion gallons of water a day used in New York City that originates from rural watersheds to points throughout the city.” And though the tunnel “is one of the largest urban projects in history, few people will ever see it. But beginning next week, many New Yorkers will certainly feel and hear the construction.”

[Images: By Ozier Muhammad for The New York Times].

[Images: By Ozier Muhammad for The New York Times].

The speed of the excavation process “varies based upon the hardness of the rock it encounters. The task of determining what type of rock lies in its path falls to Eric Jordan, a geologist hired by the city. By drilling down and hand-picking rocks from the tunnels, Mr. Jordan has created a precise map of the type of rock under Manhattan. His involvement in the tunnel project makes his geologist friends jealous. ‘For a geologist,’ he said, ‘this is like going to Disneyland.'”

Jordan’s “precise map” of Manhattan bedrock would indeed be something to see; but until then, we can make an educated guess about the rock his tunnel will find by turning to Richard Fortey.

In his highly recommended book, Earth, Fortey visits Central Park. First you notice the skyline of towers, he writes. “Then you notice the rocks. Cropping out in places under the trees are dark mounds of rock, emerging from the ground like some buried architecture of a former race, partly exhumed and then forgotten… That New York can be built so high and mighty is a consequence of its secure foundations on ancient rocks. It pays its dues to the geology. This is just a small part of one of those old seams that cross the earth… relics of a deeper time when millennia counted for nothing.”

[Image: By Ozier Muhammad for The New York Times].

[Image: By Ozier Muhammad for The New York Times].

John McPhee picks up this lithic line of thought in Annals of the Former World. Archipelago New York, he writes, is made of “rock that had once been heated near the point of melting, had recrystallized, had been heated again, had recrystallized, and, while not particularly competent, was more than adequate to hold up those buildings… Four hundred and fifty million years in age, it was called Manhattan Schist.”

Of course, we can also turn to the U.S. National Geologic Map Database, and find our very own bedrock maps –

– which, awesomely, include Times Square, Carnegie Hall, Rockefeller Center, and the Museum of Modern Art, all floating above a sea of solid Manhattan Schist.

In any case, the new tunnel being dug to power the faucets of Manhattan are supplements to the pharaonic, 19th-century Croton hydrological network that keeps New York in taps (including the now derelict, yet Historically Registered, Old Croton Aqueduct). You can read about the Croton Dam, for instance, here or here; and there’s yet more to learn about the Croton project, including how to follow it by trail, here.

[Image: Photograph by Robert Polidori, from “City of Water” by David Grann, The New Yorker, September 1, 2003].

[Image: Photograph by Robert Polidori, from “City of Water” by David Grann, The New Yorker, September 1, 2003].

Finally, in 2003 The New Yorker published an excellent article by David Grann called “City of Water,” about, yes, City Tunnel No. 3. I’ll quote from it here briefly before urging you to find a copy at your local library and read it for yourself.

Until Grann actually accompanied the tunnel workers – called sandhogs – underground, he “had only heard tales of New York City’s invisible empire, an elaborate maze of tunnels that goes as deep as the Chrysler Building is high. Under construction in one form or another for more than a century, the system of waterways and pipelines spans thousands of miles and comprises nineteen reservoirs and three lakes. Two main tunnels provide New York City with most of the 1.3 billion gallons of water it consumes each day, ninety per cent of which is pumped in from reservoirs upstate by the sheer force of gravity. Descending through aqueducts from as high as fourteen hundred feet above sea level, the water gathers speed, racing down to a thousand feet below sea level when it reaches the pipes beneath the city.”

Two main tunnels, he writes – and, thus, City Tunnel No. 3.

But I’ll stop there – after I point out that toward the end of the ludicrously bad Die Hard III, Jeremy Irons temporarily escapes the less than threatening eye of Bruce Willis by driving out of Manhattan through similar such aqueducting tunnels.

(For more tunnels: See BLDGBLOG’s London Topological or The Great Man-Made River; then check out The Guardian on London’s so-called CTRL Project, with a quick visit to that city’s cranky old 19th-century sewers, the “capital’s bowels”… Enjoy!).

Thanks for the post.

Water tunnel No. 3 in NYC makes one of the best arguments against privatization of essential pieces of infrastructure. As the Times article implies, but doesn’t explicitly state, strictly speaking, tunnel No. 3 is not necessary. It is being built so the city can periodically shut down either tunnel No. 1 or tunnel No. 2 to check out their conditions.

A private company would never invest in a $6 billion, 50-year project to create a new tunnel that was not an immediate necessity.

About a decade back, Rudy Giuliani proposed selling off the city’s water supply. Alan Hevesi, city comptroller at the time, vetoed the idea.

Still, the U.S. is busy pushing infrastructure privatization on the developing world.

rn, I find your argument surprising given that a typical justification for giving government a monopoly over infrastructure is that allowing for private competitive supply would create “wasteful duplication of effort”. As in: more tunnels, power lines, pipe networks and roads than one really needs, not fewer. The upside of “wasteful competition” is that it provides redundancy, something that tends to be sorely lacking when there is only a single monopoly provider.

For all we know, if the city got out of the business we might ultimately have ten smaller, cheaper new tunnels instead of one huge new one. To make your case you’d need to prove both (a) that this particular tunnel is ultimately necessary in exactly the size and configuration the city is building, and (b) that private industry wouldn’t be able to meet the underlying need (either with a similar tunnel or with some appropriate substitute technology) in less time and at lower cost.

(Note that if the tunnel isn’t necessary, it’s a feature rather than a flaw that private industry would resist spending billions on it.)

The tunnel is extremely necessary. The two other tunnels, built in 1915 and 1933, have never been shut down for maintenance. There is no other way to distribute the water around the city, and it is too dangerous to turn off even one small section, since the valves may be too rusty to operate. A third tunnel is required to take the place of one of the others while long-overdue repairs can be made.

Regarding privatization, I think it’s pretty farfetched to think you could find a company that could take on a 50 year project costing billions of dollars. and even if you could, I wouldn’t want them meddling in what is a promary public service that is actually provided to the city in a very efficient manner.

Stanley Greenberg, author, “Waterworks: A Photographic Journey Through New York’s Hidden Water System”

Now that I’ve done a tiny bit of research, I’m even more mystified. This work is being done largely by private contractors:

“Grow Tunnelling Corporation, Perini Corporation and Skanska JV, all of the USA have been awarded the latest segment known as the Queens Tunnel, City Tunnel No. 3, Stage 2 segment. “

Is your claim that the private sector would somehow be incapable of paying the same contractors to do this job?

What makes it less likely the private sector could build a profitable and reliable underground water system than that it could build the Empire State Building? Or build a New York subway system such as the IRT (1900) or the BMT (1915)?

“A private company would never invest in a $6 billion, 50-year project to create a new tunnel that was not an immediate necessity.” rn (above)

That notion falls flat, even on the basis of anecdotal evidence. What railway company refused to build a second set of tracks that weren’t immediately necessary? What highway contracter refused to build additional lanes when there were existing detours built at public expense? What toll road developer refused to build a toll road when there were public highways within a few miles on a parallel route? What bridge builder refused to construct a bridge when people could drive around the bay? What tunnel builder refused to build a tunnel because other tunnels already existed? And what underground railway refused to develop new routes because there were already alternative ways of getting to the same points? Does Eurostar mean anything to you? Does the Channel Tunnel? How about London Undergound? Crossrail? These are just cursory examples, and maybe you can dismiss each of them for various reasons. When you do, and not before, I’ll acknowledge the validity of that claim.

Now that the NY Times has opened its archives, the photos were taken by Ozier Muhammad.

James, indeed; I hadn’t revisited this post in more than two years, but will make the update. Thanks!